Last year, an en banc Federal Circuit ruled in the seminal case of Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc. that the so-called “point of novelty” test was no longer valid in determining design patent infringement. Instead, design patent infringement was to be judged solely by the “ordinary observer” test from the 1871 Supreme Court case of Gorham Mg. Co. v. White. But what test should be used in determining the validity of a design patent? A Federal Circuit panel in International Seaway Trading Corp. v. Walgreens Corp. unanimously answered that the validity of design patents must likewise be judged solely by the “ordinary observer” test.

Last year, an en banc Federal Circuit ruled in the seminal case of Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc. that the so-called “point of novelty” test was no longer valid in determining design patent infringement. Instead, design patent infringement was to be judged solely by the “ordinary observer” test from the 1871 Supreme Court case of Gorham Mg. Co. v. White. But what test should be used in determining the validity of a design patent? A Federal Circuit panel in International Seaway Trading Corp. v. Walgreens Corp. unanimously answered that the validity of design patents must likewise be judged solely by the “ordinary observer” test.

In International Seaway Trading, three design patents relating to shoe designs for “casual, lightweight footwear” (typically referred to as “clogs”) were alleged to be infringed. One of these three design patents was U.S. Design Patent No. D529,263 (“the ‘263 patent”) which became the focus of the opinion in International Seaway Trading. The district court granted the defendants summary judgment based on invalidity of these three patents (including the ‘263 patent) as anticipated under 35 U.S.C. § 102 in view of U.S. Design Patent No. D517,798 (“the Crocs ‘789 patent”).

In determining that the ‘263 patent was anticipated, the district court applied only the “ordinary observer” test in comparing the shoe design in the ‘263 patent to that of the Crocs ‘789 patent. As stated (and refined) by the Federal Circuit in the Egyptian Goddess case, the “ordinary observer” test requires an ordinary observer to consider whether the two designs being compared are “substantially the same” (the original Gorham test), taking into account the “differences between the patented design and the accused product in the context of the prior art” (the Egyptian Goddess refinement of the Gorham test).

A comparison of the side profiles only of the exterior of the shoe design (FIG. 2 of the ‘263 patent to FIG. 1 of the Crocs ‘789 patent) suggests why the district court reached the conclusion that the ‘263 patent was anticipated by the Crocs’ 789 patent:

But the district court also concluded that a comparison of the insoles of these shoe designs was unnecessary because those portions of the shoe design would invisible during normal use “regardless of whether those portions are visible during the point of sale.”

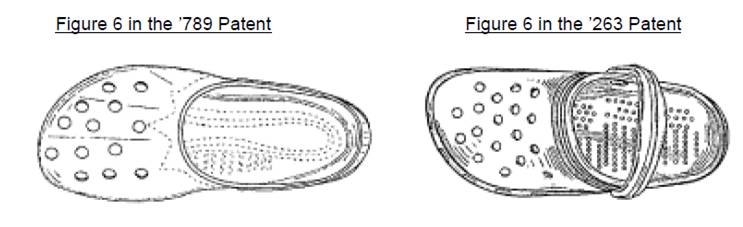

A comparison of the top profiles of these shoe designs (FIG. 6 of the ‘263 patent to FIG. 6 of the Crocs ‘789 patent) reveals some fairly evident differences between these insole designs:

Whether I can be considered an “ordinary observer” or not (I’m an undergraduate chemist), it’s pretty clear these insole designs are strikingly different. The insole design for the Crocs ‘789 patent involves a series of nested elongated U-shaped dimple patterns. By comparison, the insole design of the ‘263 patent includes multiple, generally linear horizontal short rows of dimples. In fact, these top profiles also reveal some subtle but also distinct differences in the number, positioning, and shape of the somewhat circular openings on the upper outer sole. Even the side profiles show some subtle differences in the positioning, number, and shape of the rectangular openings on the lower portion of the front outer sole.

The design patentee (Seaway) appealed the grant of summary judgment, arguing that the district court should have also applied the “point of novelty” test rejected in Egyptian Goddess. The Federal Circuit panel unanimously agreed that the district court was correct in applying only the “ordinary observer” test in judging the validity of the ‘263 patent. The Federal Circuit panel observed that, prior to Egyptian Goddess, Federal Circuit cases had used the “point of novelty” test for both infringement and anticipation. But the Federal Circuit also observed that “for over a century that the same test must be used for both infringement and anticipation” for utility patent, and that therefore the “same rule applies for design patents.” Accordingly, because Egyptian Goddess held that the “ordinary observer” test was the sole test for design patent infringement, likewise the ordinary observer” test must “logically be the sole test for anticipation” of design patents.

Where the Federal Circuit panel parted company with the district court was in excluding the insole design from consideration in the validity determination of the ‘263 patent. In excluding the insole design, the district court had relied upon the 2002 Federal Circuit decision in Contessa Food Products, Inc. v. Conagra, Inc. which held that the infringement inquiry shouldn’t be limited to features visible at the time of sale to exclude those visible at any time during normal use of the accused product. But the Federal Circuit panel in International Seaway Trading asserted that the district court has misconstrued Contessa as requiring only consideration of design features visible during normal use.

Instead, what the Federal Circuit panel said Contessa emphasized was that “normal use should not be limited to only one phase or portion of the normal use lifetime of an accused product.” Accordingly, “the point of sale of the clog clearly occurs during its normal use lifetime.” And at the point of sale, “the insole is visible to potential purchasers when the clog is displayed on a shelf or rack and when the clog is picked up for examination.” That meant that the insole portion of the shoe design must be considered in the validity determination of the ‘263 patent.

There was also a disagreement between a majority of the panel (Judges Dyk and Bryson) and partially dissenting Judge Clevenger over the impact of the exterior features, of the shoe design, namely the differences in the positioning, number, and shape of rectangular and circular openings on the outer sole. The panel majority agreed with the district court that these “minor variations in the shoe are insufficient to preclude a finding of anticipation because they do not change the overall visual impression of the shoe.” In other words, the panel majority dismissed these “minor variations” as having any impact on the validity determination of the ‘263 patent.

Judge Clevenger’s partially dissenting opinion chided the panel majority for permitting “dissection of a design as a whole into its component pieces.” In fact, Judge Clevenger characterized the panel majority as creating a new “design as a whole” rule which “does not prevent the district court on summary judgment from determining that individual features of the design are insignificant from the point of view of the ordinary observer and should not be considered as part of the overall comparison.” Judge Clevenger further asserted that the panel majority’ reliance on Litton Systems, Inc. v. Whirlpool Corp. for this new rule was “misplaced” and ran “counter to precedent,” citing the 1992 case of Braun Inc. v. Dynamics Corp. (“In evaluating a claim of design patent infringement, a trier of fact must consider the ornamental aspects of the design as a whole and not merely isolated portions of the patented design”), as well as the 1959 CCPA case of In re Rubinfield(“It has been consistently held for many years that it is the appearance of a design as a whole which is controlling in determining questions of patentability and infringement”).

Frankly, I side with Judge Clevenger that the panel majority glossed over the “design as a whole” rule. In dismissing the exterior features as “minor variations,” the panel majority gives no apparent consideration to the fact that these exterior features (i.e., the somewhat circular openings in the upper outer sole) are plainly visible in combination with the insole designin FIG. 6 of the ‘263. How these exterior features can be simply dismissed by the panel majority as “minor variations” when plainly visible along with the insole design, yet do justice to the “design as a whole” rule, is hard to fathom. And Judge Clevenger is certainly not out of line in suggesting that the differences in the positioning, number, and shape of rectangular and circular openings on the outer sole between the respective shoe designs (especially as shown in the respective FIGS. 6) may be more than “minor variations.”

The Federal Circuit panel in International Seaway Tradinghas at least resolved what test is to be applied in judging the validity of design patents. Where the divergence comes is how to apply the “ordinary observer” test, and particularly what does the “design as a whole” rule mean when determining validity under that test. Put differently, the Federal Circuit still has some work to do in resolving the “ordinary observer” test issues left over from its en banc ruling in Egyptian Goddess.

*© 2009 Eric W. Guttag.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IP-Copilot-Apr-16-2024-sidebar-700x500-scaled-1.jpeg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

One comment so far.