As I’ve said before, no one could rightly accuse me of being biased against patents. See Judge Rader Doth Protest Too Much in Media Technologies. But, as I also pointed out in this article on Judge Rader’s dissent in Media Technologies Licensing, LLC v. The Upper Deck Company, I don’t believe every patent is “bullet proof,” or to use Judge Plager’s phrase, that some patents aren’t built on “quicksand.” In fact, I agree with Judge Plager’s dissent in the denial of rehearing en banc in Enzo Biochem, Inc. v. Applera Corp., issued May 26, 2010, which argues that the “definiteness” requirement in the second paragraph of 35 U.S.C § 112 needs more “teeth” than Federal Circuit precedent appears to give it.

As I’ve said before, no one could rightly accuse me of being biased against patents. See Judge Rader Doth Protest Too Much in Media Technologies. But, as I also pointed out in this article on Judge Rader’s dissent in Media Technologies Licensing, LLC v. The Upper Deck Company, I don’t believe every patent is “bullet proof,” or to use Judge Plager’s phrase, that some patents aren’t built on “quicksand.” In fact, I agree with Judge Plager’s dissent in the denial of rehearing en banc in Enzo Biochem, Inc. v. Applera Corp., issued May 26, 2010, which argues that the “definiteness” requirement in the second paragraph of 35 U.S.C § 112 needs more “teeth” than Federal Circuit precedent appears to give it.

The three patents, U.S. Pat. No. 5,328,824 (the ‘824 patent), U.S. Pat. No. 5,449,767 (the ‘767 patent), and U.S. Pat. No. 5,082,830 (the ‘830 patent), in Enzo Biochem involved compounds used in techniques for labeling and detecting nucleic acids. The district court granted summary judgment of invalidity of all of the asserted claims of each of these patents based on “indefiniteness” under 35 U.S.C § 112, second paragraph, or alternatively as anticipation under 35 U.S.C § 102. The “indefiniteness” ruling for each of the three patents related primarily to the phrase “not interfering substantially.” This phrase was used to define a linkage group present in the claimed compounds as “not substantially interfering” with the function of these compounds as detection probes with respect to both hybridization and detection (the ‘824 and ‘767 patents) or simply detection (the ‘830 patent).

In reversing this portion of the district court ruling, the Federal Circuit panel in Enzo Biochem (Judge Linn writing the opinion along with Judge Plager and Chief Judge Michel) agreed with the patentee (Enzo Biochem) that the asserted claims of these three patents weren’t “indefinite.” Citing the 2003 Federal Circuit decision of Deering Precision Instruments, LLC v. Vector Distrib. Sys. Inc., the Federal Circuit panel in Enzo Biochem observed that “substantially,” when used in a claim, can denote either language of approximation or magnitude. In the claim phrase “not substantially interfering,” the word “substantially” was viewed as denoting language of magnitude “because it purports to describe how much interference can occur during hybridization, i.e., an insubstantial amount of interference” (emphasis in the original), citing the 2002 Federal Circuit case of Epcon Gas Sys., Inc. v. Bauer Compressors, Inc.

Accordingly, with respect to “hybridization,” the claimed invention provided “at least some guidance as to how much interference will be tolerated.” Judge Linn’s also cited the specification which provided “additional examples of suitable linkage groups, including some of the criteria for selecting them,” as well as the prosecution history, as additional intrinsic evidence that would enable the personal of ordinary skill in the art (aka the PHOSITA) to determine the scope of the claims, including the meaning of “not substantially interfering.” With regard to “detection,” Judge Linn’s opinion agreed with Enzo Biochem that the claims were “not indefinite for most of the same reasons” discussed with respect to “hybridization.”

Interestingly, Judge Plager’s disagreement regarding the “definiteness” of the asserted claims in Enzo Biochem didn’t surface until the later denial of rehearing en banc. At that point, Plager suggested there were “varying formulations” that the Federal Circuit had used to describe its “indefiniteness” jurisprudence (much like the differing standards of “materiality” noted in the 2006 case of Digital Control Inc. v. The Charles Machine Works in determining “inequitable conduct”). Plager also observed (perhaps with a judicial “sigh”) that:

the problem [“indefiniteness”] is not one of an inherently ambiguous and potentially indefinite claim term, but rather the problem becomes simply one of picking the “right” interpretation for that term. Since picking the “right” interpretation—claim construction—is a matter of law over which this court rules, and since the view of the trial judge hearing the case is given little weight, so that the trial judge’s view on appeal becomes just a part of the cacophony before this court, it is not until three court of appeals judges randomly selected for that purpose pick the “right” interpretation that the public, not to mention the patentee and its competitors, know what the patent actually claims. The inefficiencies of this system, and its potential inequities, are well known in the trade.

Judge Plager took note of the “contrasting” efforts by the USPTO “to give the statutory requirement [of 35 U.S.C § 112, second paragraph,] real meaning.” This included John Love’s 2008 five-page memo instructing the examining corps on “[i]ndefiniteness rejections under 35 U.S.C. 112, second paragraph.” Plager also cited the 2008 Board of Appeals and Interferences decision in Ex parte Miyazaki as “clearly right in insisting that, if the public notice function of the patent law is to be honored, claim terms must particularly point out and distinctly claim the subject matter of the invention.” In Miyazaki, the Board held that “if a claim is amenable to two or more plausible claim constructions, the USPTO is justified in requiring the applicant to more precisely define the metes and bounds of the claimed invention by holding the claim unpatentable under 35 U.S.C. § 112, second paragraph, as indefinite.”

Judge Plager argued that the Federal Circuit could go further in promoting this “[notice function] than it currently does, with the not inconsequential benefit of shifting the focus from litigation over claim construction to clarity in claim drafting.” And Plager wanted the Federal Circuit to move now in that direction with the Enzo Biochem case:

The court now spends a substantial amount of judicial resources trying to make sense of unclear, over-broad, and sometimes incoherent claim terms. It is time for us to move beyond sticking our fingers in the never-ending leaks in the dike that supposedly defines and figuratively surrounds a claimed invention. Instead, we might spend some time figuring out how to support the PTO in requiring that the walls surrounding the claimed invention be made of something other than quicksand. (Emphasis added.)

Ouch! Judge Plager’s dissent is a pretty strong indictment about the Federal Circuit’s jurisprudence on the “definiteness” requirement of the second paragraph of 35 U.S.C. 112. But with some “reservations” about the citation to the Love memo, I frankly agree with Plager that the “definiteness” requirement hasn’t stringently enough by the Federal Circuit to screen out poor drafted or ambiguous claims. Let’s also be clear that there’s nothing inherently wrong with the term “substantially” (I’ve used it in many patent applications), or the phrase “not interfering substantially” used in the asserted claims of the three patents in Enzo Biochem. But terms like “substantially” which are relative in scope should perhaps be more carefully defined in the patent specification (as should other key claim terms) so that the meaning of the term is clear to at least the PHOSITA, especially in the context of the claimed invention.

I also wouldn’t be opposed to a more stringent “enablement”/”written description” requirement according to the first paragraph 35 U.S.C § 112. As I’ve expressed before, 35 U.S.C § 112 is a better initial screen for poorly defined inventions (including the claimed method in Bilski v. Kappos), when compared to “patent-eligibility” under 35 U.S.C § 101. See The Bilski Oral Argument Speaks Volume: Start with 35 U.S.C. § 112 . By using 35 U.S.C § 112 as the initial screen, we might at least minimize the reliance upon the elusive “patent-eligibility” standard of 35 U.S.C § 101 which is a very imprecise and subjective screen, as witnessed in Bilski where even the Supreme Court Justices at oral argument appeared to be hopelessly confused over the difference between “patentable” and “patent-eligible.” With 35 U.S.C § 112 as our initial guide, we would at least have a better chance to objectively screen out the patent claim “chaff,” rather than to “sink” hopelessly into the subjective “quicksand” of what is “patent-eligible” subject matter based on the nonsensical “machine or transformation” test (or whatever other test SCOTUS ultimately decides is appropriate) in Bilski.

© 2010 Eric W. Guttag.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

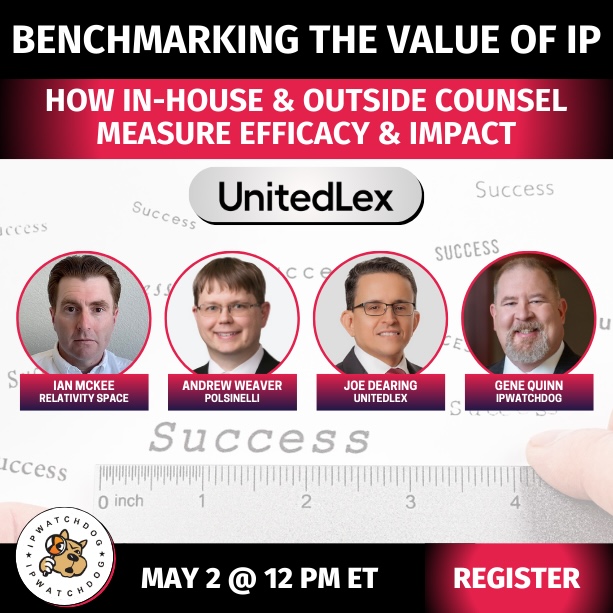

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Quartz-IP-May-9-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

One comment so far.

Scott Daniels

June 1, 2010 03:37 pmThe power of Judge Plager’s dissent lies in the fact that he is absolutely right. Words of approximation are a long-time part of claim drafting, but they undermine the public notice function of claims. In some cases, they create not merely two or three possible constructions, but a continuum of constructions. Nice piece Eric.

Scott Daniels

Westerman Hattori Daniels & Adrian