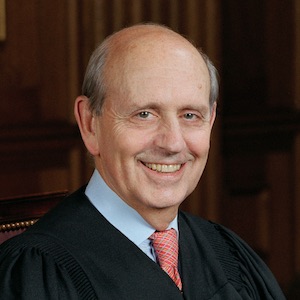

On Monday, June 17, 2013, the United States Supreme Court issued its much-anticipated decision on so-called “reverse payments” in FTC v. Actavis, Inc. This decision will impact how brand name drug companies and generics enter into patent settlements to resolve pending patent litigation. In a nutshell, speaking for the majority, Justice Breyer wrote that there is no valid reason for the FTC to be denied the opportunity to pursue reverse payments as an antitrust violation. Breyer, who was joined by Justices Kennedy, Ginsberg, Kagan, and Sotomayor, determined that reviewing courts should apply the rule of reason when determining whether reverse payments violate antitrust law.

While the ruling will likely come as no shock to casual observers, or even to those who have long believed that these agreements were anticompetitive, it is a bit of a shock in that the decision seems to present an unrealistic utopian view of how challenges to reverse payments will be litigated. For reasons hardly explained, Breyer thinks that it will be largely unnecessary for reviewing courts to engage in complicated review of the patent or to engage patent issues, but at the heart of these cases is the underlying patent and associated patent laws that give brand name manufacturers significant and uncompromised rights to exclude.

Chief Justice Roberts explained in his dissent, who was joined by Justices Scalia and Thomas, that it was his view the decision of the majority “weakens the protections afforded to innovators by patents, frustrates the public policy in favor of settling, and likely undermines the very policy it seeks to promote by forcing generics who step into the litigation ring to do so without the prospect of cash settlements.”

Justice Alito took no part in the decision, recusing himself from the case.

The Hypothetical

Justice Breyer, writing for the majority, started his decision with a hypothetical that summarizes the core factual scenario. Breyer wrote:

Company A sues Company B for patent infringement. The two companies settle under terms that require (1) Company B, the claimed infringer, not to produce the patented product until the patent’s term expires, and (2) Company A, the patentee, to pay B many millions of dollars. Because the settlement requires the patentee to pay the alleged infringer, rather than the other way around, this kind of settlement agreement is often called a “reverse payment” settlement agreement.

The issue to be determined by the court was whether this type of agreement could be a violation of the antitrust laws.

It seems perfectly clear that these types of agreements could, in some ways, be anticompetitive, but to be an antitrust violation the anticompetitive effects need to outweigh the pro-competitive effects. Excuse me for noticing the unassailable reality that the brand name drug in question wouldn’t even exist without a patent incentive existing in the first place. So to focus on reverse payments and whether they may or may not be too anti-competitive misses the inescapable reality that without the significant investment in research and development there wouldn’t be any market for the drug in question and it would be completely moot to even entertain a discussion about whether the marketplace is negatively impacted by these agreements. The marketplace exists because of the time, money and hard work that occurs as a direct result of the patent incentive. The creation of the market under the laws explicitly authorized by Congress really ought to mean something.

Still, the larger question shouldn’t be whether the agreements are or can be anti-competitive, but rather it should be whether the agreements are authorized by law. It seems to me that the position taken by the majority is fundamentally misguided. Congress authorizes patenting and allows for reverse payments under the Hatch-Waxman regulatory structure and yet the Supreme Court, in their infinite wisdom, allows the Federal Trade Commission to seek to punish those who engage authorized conduct.

Hatch-Waxman and Congressional Ranting

Anyone familiar with the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Amendments to the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act knows that gaming the system is something that can be accomplished with extraordinary ease, at least it was, until now. As a result of a healthy dose of extremely specific and narrowly tailored provisions, gaming the system is a way of life under Hatch-Waxman. No one seriously disagrees that gaming the system occurs, but rather there is disagreement over whether such gaming of the system should be tolerated given Congressional inaction and specific provisions of the law that authorize such gaming.

Further complicating the Hatch-Waxman gaming is that Congress has been well aware of it for many, many years. There have been numerous attempts to modify the law to prevent the gaming, none of which have ever been enacted by Congress. Thus, many Courts followed the age-old statutory construction guidelines and judicial conservatism, which mandates that if Congress knows of a problem and does nothing to stop it then it must have been intended, or at least tolerated. Thus, because Congress has long known about reverse-payments, the Hatch-Waxman Act allows for it to happen and Congress has never put a stop to the payments, it was reasonable for courts to believe that there was no logical way that the payments could violate antitrust laws. After all, how can Congress authorize actors to act and then the courts find the authorized action to be illegal?

The whole purpose of Hatch-Waxman was to make it easier for a generic drug manufacturer to piggyback on the studies previously submitted by the original inventor of a new drug. In the United States, in order for a new drug to receive market approval a New Drug Application, known as an NDA, must be submitted to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). To lessen the burden on generics, Hatch-Waxman allows generic manufacturers to submit Abbreviated New Drug Applications, known as ANDAs. In the event that the generic manufacturer can establish that the drug mentioned in the ANDA is the bioequivalent of a drug approved in a NDA, the generic manufacturer can sail through approval by relying on the costly and time-consuming studies previously submitted as a part of the NDA.

The real wrinkle in Hatch-Waxman, at least in patent terms, comes with respect to certain statements that must be made by the generic manufacturer in the ANDA. Indeed, an ANDA applicant must make one of four certifications regarding each patent that applies to the drug for which approval is being sought: (I) no such patent information has been submitted to the FDA; (II) the patent has expired; (III) the patent is set to expire on a certain date; or (IV) the patent is in valid or will not be infringed by the drug covered in the ANDA. It is the paragraph IV certifications that are the most interesting. Although making a paragraph IV certification is not an active act of infringement, thanks to specific legislation, when a paragraph IV certification has been made, the patent owner of the drug covered by the NDA may immediately institute infringement proceedings. Not only may an infringement action be instituted, but also if one is instituted, an 18-month automatic stay goes into effect, during which time the FDA cannot legally approve an ANDA. What many patent owners have done is institute lawsuits to enjoy a further 18-month automatic stay, and have even sought to seek consecutive 18-month stays. Such gaming is old news really, but generic manufacturers have still been enticed to file ANDAs because the statute provides a 180-day exclusivity period to the first ANDA applicant to file a paragraph IV certification. Thus, Congress has provided the incentive, in the form of a promised 180-day oligopoly, for those who would challenge the scope and validity of drug patents.

The particular gaming of the system involved in this case, however, deals with whether the brand name drug manufacturer can pay the generic company to settle a patent infringement case and keep the generic out of the market for a period of time as the result of a mutually agreed resolution to an ongoing litigation.

The Supreme Court Decision

In this case Solvay Pharmaceuticals obtained a patent for its approved brand-name drug AndroGel. Subsequently, Actavis and Paddock filed applications for generic drugs modeled after AndroGel and certified under paragraph IV that Solvay’s patent was invalid and that their drugs did not infringe it. Solvay sued Actavis and Paddock, claiming patent infringement. Even though the FDA approved the generic form of AndroGel, Actavis entered into a “reverse payment” settlement agreement with Solvay. This agreement was for Actavis not to bring its generic to market for a specified number of years. Actavis was paid millions of dollars under the settlement. Paddock made a similar agreement with Solvay, as did other manufacturers.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) filed suit, arguing that the reverse payments violated §5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act. The FTC believed that it was unlawful for the generic manufacturers to abandon their patent challenges and refraining from launching low-cost generic drugs. The District Court dismissed the complaint and the Eleventh Circuit concluded that the anticompetitive effects of a settlement fall within the scope of the patent’s exclusionary rights and were immune from antitrust attack. Furthermore, the Eleventh Circuit sensibly ruled that public policy favors settlement of disputes and courts could not require parties to continue to litigate in order to avoid antitrust liability.

The Supreme Court, however, had different ideas. The Supreme Court explained that reverse payment agreements are not immune from antitrust review simply because it might ultimately be determined that the anticompetitive effects of the reverse settlement agreement rightfully fall within the scope of the exclusionary potential of underlying patent.

In fact, the Supreme Court explained that the FTC should be at least given the opportunity to demonstrate that reverse payments violated antitrust laws for at least several reasons. Most curiously, however, was the second of the five rationales for allowing the FTC to move forward to attempt to prove an antitrust violation. The Supreme Court explained that while there may be justifications for reverse payment that are not the result of having sought or brought about anticompetitive consequences, the “anticompetitive consequences will at least sometimes prove unjustified.” How the Court can say this definitively is curious given the procedural posture of the case? The case was disposed of by the District Court on a motion to dismiss, which is a procedural disposal that happens at the earliest stages of the case, typically without any discovery and little to no factual development of the record. Still, the Supreme Court knows in its infinite wisdom that some cases of reverse payment will be antitrust violations since they are unjustified anti-competitive agreements?

That the Supreme Court would make such a blanket statement that they know without any evidence or factual development that some reverse payments will have unjustified anti-competitive consequences is nearly breathtaking. Not because of the audacity of the statement, but because such clear overreaching has been and continues to be the lasting trademark of this Supreme Court, who seems to think they know better than everyone about everything. They are experts on all things and nothing is beyond their knowledge and experience. Not difficult questions of science and certainly not extraordinarily complicated issues of law, economics, and patent jurisprudence wrapped up in this case.

Truthfully, that the Supreme Court already knows that some reverse payments will be unjustified is hardly shocking. Increasingly it seems that this Supreme Court is willing to step outside the record below and even rely on statements in amicus briefs as evidence. We witnessed this just last week in Myriad where the Supreme Court reviewed the issue of gene patenting in a case that was disposed of on Summary Judgment where the most fundamental facts were in dispute (i.e., namely whether a claim to isolated DNA covers something that is naturally occurring).

Thankfully the Supreme Court was at least willing in this case to concede the obvious, which is not something they always show a willingness to do. Justice Breyer explained:

We concede that settlement on terms permitting the patent challenger to enter the market before the patent expires would also bring about competition, again to the consumer’s benefit.

And the Court did not find that reverse payments are per se unlawful, but rather that reviewing courts should review the legality of such agreements by applying the rule of reason. That essentially requires a consideration of the totality of the circumstances. Thus, agreements that ultimately wind up with the generic in the market prior to the expiration of the patent should certainly fair better than the FTC might hope for given that the Supreme Court has acknowledged that such an agreement is pro-competitive and can offset other anti-competitive effects.

Still, I can’t shake the unfortunate reality that Congress authorizes these types of settlements. Yes, it is due to the byzantine and bizarre structure of Hatch-Waxman, but Congress has never fixed the gaming of the system and the law does allow for reverse payments. How can something that is authorized by Congress be an anti-trust violation? It makes no sense to be given a right and then told you are violating the law by exercising the given right. Only in a Bizarro world would you get a right that you have no right to legally exercise

Unlike some of the truly head scratching and unanimous decisions from the Supreme Court, Chief Justice Roberts, Justice Scalia, and Justice Thomas did understand the issues better than the Breyer lead majority. Roberts wrote that the majority’s rationales for allowing the FTC allegations to proceed were all “unresponsive to the basic problem that settling a patent claim cannot possibly impose unlawful anticompetitive harm if the patent holder is acting within the scope of a valid patent and therefore permitted to do precisely what the antitrust suit claims is unlawful.”

Roberts also correctly pointed out the fallacy of the majority saying that it will be unnecessary to litigate patent issues in context of an antitrust case. It most certainly will! Roberts correctly explained:

I therefore don’t see how the majority can conclude that it won’t normally be “necessary to litigate patent validity to answer the antitrust question,” unless it means to suggest that the defendant (patent holder) cannot raise his patent as a defense in an antitrust suit. But depriving him of such a defense—if that’s what the majority means to do—defeats the point of the patent, which is to confer a lawful monopoly on its holder.

Conclusion

This is one of those cases where the wrong decision may wind up benefitting the public, but at what cost? The Supreme Court is not supposed to be a venue where “the right decision” is reached case-by-case, but rather a forum to decide the most important issues. Overstepping their boundaries and becoming a super-legislature may bring greater justice to a single case, but it erodes the very fabric of separation of powers and makes the Court less legitimate, which will do irreparable harm to what is supposed to be an apolitical branch of government.

Of course, there is also a very real chance that this wrong decision will do far more harm than good. What company in their right mind would enter into an agreement in a public forum that would open them up to antitrust scrutiny? Avoiding antitrust scrutiny is a cottage industry and clients rightfully want to avoid regulators at all costs. But if settling a patent litigation could provoke antitrust scrutiny then it seems to be a perfectly reasonable business decision to either not settle or not bring the challenge in the first place. Given that fighting to the end to win a case is what is required if no settlement can be achieved, it seems likely that at least some, perhaps many, will opt to not pursue these types of paragraph IV certifications, which would mean that generic drugs will be delayed from reaching the market. If that happens, which seems certainly plausible, this decision will not only have further eroded a patent owner’s rights but also result in harm to society.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

3 comments so far.

Gene Quinn

June 18, 2013 04:13 pmAnon-

Yes, the Supreme Court has been a political forum for years, which is unfortunate.

EG-

The FTC wanted these to be per se illegal so they don’t have to engage in the difficult work of weighing the positives and negatives. As we know, rule of reason cases are extraordinarily complicated and under the rule of reason if the patent right is appropriately weighed these will unlikely be found to be an antitrust violation.

But defending an antitrust case is difficult enough. Defending when a rule of reason is required will be extremely costly if the FTC wants to go after companies and punish them. Thus, it is hard to see any viable business model that would allow generics to file paragraph IV certifications and then settle cases. Opening themselves up to antitrust scrutiny would be suicide. I believe this decision will reduce the likelihood of generics entering the market prior to the expiration of the patent. Time will tell.

Cheers.

EG

June 18, 2013 08:35 am“For reasons hardly explained, Breyer thinks that it will be largely unnecessary for reviewing courts to engage in complicated review of the patent or to engage patent issues.”

Gene,

That is wishful thinking on Breyer’s part if you use a “Rule of Reason” approach to reverse payments. But also remember that the FTC urged a presumptively illegal/per se illegal approach to reverse payments which all 8 Justices rejected, thus undermining the rationale in the 3rd Circuit’s ruling in K-Dur which the FTC so slavishly sought in Actavis.

Anon

June 18, 2013 07:19 amThe Court stopped being an ‘apolitical’ branch a long time ago.