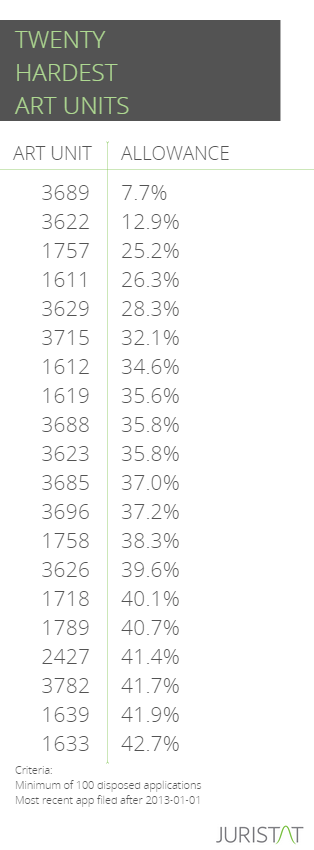

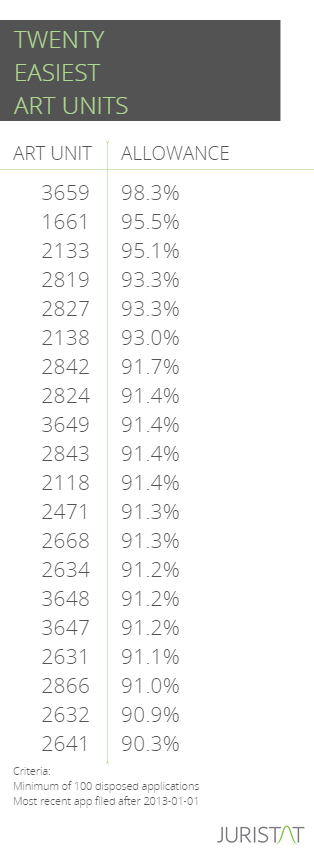

It should come as no surprise that allowance rates vary widely among art units. After all, certain factors affect certain applications more than others. One need only consider Alice Corp. and its impact on software-related business methods. Nevertheless, practitioners may be surprised by the size of the spread. These are the 20 art units with the highest and lowest allowance rates:

For these lists, we considered only art units with at least 100 disposed applications. We also limited our analysis to those art units in which the most recent application was filed after January 1, 2013. Finally, we excluded design art units. Let’s take a closer look.

Art Unit 3689 has the lowest allowance rate at 7.7%. Art Unit 3659 has the highest at 98.3%. Oddly enough, these two art units are from the same technology center. It’s worth noting, however, that the 3600s deal with a variety of inventions, including transportation, e-commerce, and national security.

Of the 20 art units with the lowest allowance rates, eight are in the 3600’s. This is not surprising. After all, the 3600’s host many business-method art units. In Alice Corp., the Supreme Court rejected claims describing a method for mitigating settlement risk. According to the Court, the claims did not contain an “inventive concept” sufficient to “transform” the abstract idea into a patent-eligible application. Since that case, and particularly after the June 25, 2014 USPTO memo, there has been a significant jump in section 101 rejections, especially with regard to software-related business methods. This increase is well documented.

Outside of the 3600’s, another five of the hardest art units come from the 1600’s – biotech and organic chemistry. Again, this is not surprising, especially in light of Mayo and Myriad. In Mayo, the Court found that a process for determining the proper dosage of a drug was patent ineligible as it was directed at a law of nature. In Myriad, the Court similarly held that naturally occurring gene sequences were not patentable. On March 4, 2014, the UPSTO issued new guidance in response to these cases. As a result, art units dealing with biotech and organic chemistry have seen a significant increase in section 101 rejections. While the more recent “2014 Interim Guidance on Subject Matter Eligibility” supersedes the March 4 guidance, we expect Mayo and Myriad will continue to play a significant role.

If we turn our attention to the easiest art units, we see that six hail from the 2800s – semiconductors, circuits, optics, and printing. Another five are found in the 2600s, dealing with communications. Finally, four of the highest allowance rates come from the 3600s, making it the most represented technology center between the two lists.

To break things down even further, four of the most difficult art units deal specifically with electronic commerce (the 3620s). On the other hand, three of the easiest art units cover digital communications (the 2630s). Another three of the easiest art units come from the 3640s. According to the USPTO’s website, this group is responsible for a wide range of subject matter, from vermin destruction to nuclear systems.

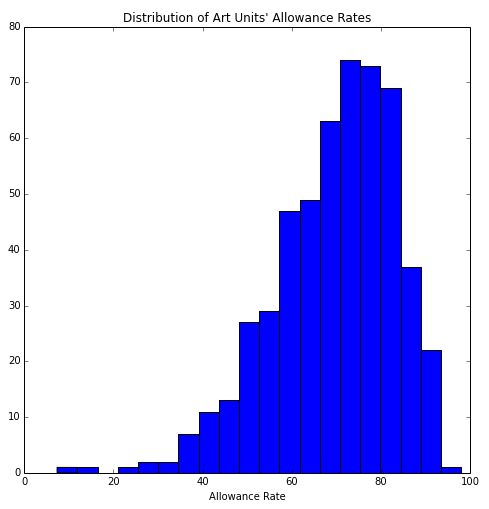

Represented graphically, the distribution of allowance rates among all art units at the USPTO looks like this:

The graph is skewed right, with a plurality of art units allowing between 70-75% of applications. Nevertheless, it’s clear that art unit plays a significant role in patent prosecution. An application assigned to 3689 is 90.6% less likely to receive an NOA than an application assigned to 3659.

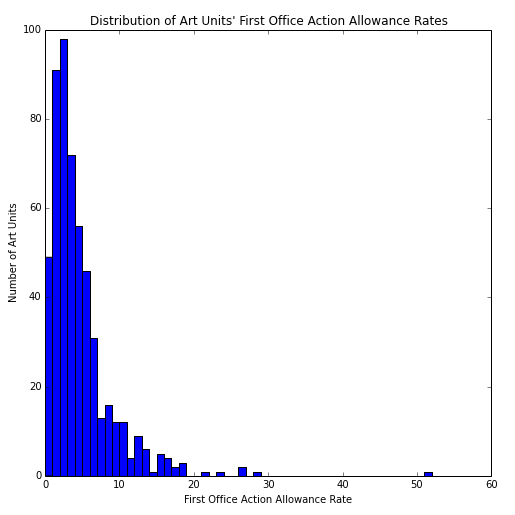

Not surprisingly, if we consider only first office action allowance rate, the graph looks entirely different:

A vast majority of art units allow fewer than 10% of applications at the first office action, with a plurality of art units allowing only about 2% of applications at this stage. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. While it would certainly save time and money if more applications were accepted at this point, an immediate NOA often means the applicant is underselling his or her invention. As Jeffrey Schox states in his book Not So Obvious: “[B]ecause the prosecution process is considered a negotiation with the USPTO, patent applications that have been accepted without any rejections are often suspected of having too narrow of patent scope.” A colleague of mine put it this way: if one’s new employer immediately accepts the employee’s first salary demand, the employee should’ve asked for more money.

We expect to see changes as cases like Bilski, Alice Corp., Mayo, and Myriad continue to affect the examination process. We will continue to update the list as new cases and guidances come down.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

5 comments so far.

JExaminer

July 8, 2015 12:39 pmI think the terms “easiest” and “hardest” are a bit of a misnomer/misdirection. Simply switching art units may not have anything to do with whether or not your claim is allowable. Things like art crowdedness, art complexity, average claim scope breadth, subject matter legality (i.e. 101 issues), and type of Applicant all factor into these rates. The cited computer hardware art units probably have a high rate of allowance due to often being breakthrough technology with a clearly delineated prior art/legal history, coming from wealthy, large corporations/universities with the money to prosecute to allowance (IBM comes to mind) whereas other areas like roofing products are extremely crowded, have prior art in numerous places across classifications (both CPC/USPC have zany class systems for these), from smaller companies/independent inventors, and often have initially broader claim scopes. That doesn’t mean that abandonment does not happen in the first group and allowances don’t happen in the second, but as an examiner that examines patents in both groups (my area is complicated), I see why certain art units have higher rates of allowance and others do not.

My art unit is just outside of the twenty lowest (~45% based on this FY) and my allowance rate would fall within the 20 hardest art units range. I think this is because applications end up in my art unit because their claim scope is usually broad, thus they end up with more prior art and more types of prior art than they initially considered and longer prosecution or more narrowing than they initially intended/prepared for. On the art unit’s end, one day can be spent examining a mobile phone housing and diaper parts the next. Taking claim scope, which in my AU is often broader than the particular invention (i.e. the diaper part anticipated by housewrap, the phone housing anticipated by auto parts) into account, it might take the examiner (and the applicant) a round or two to fully understand the breath/types of the prior art and sometimes the invention. I’m not only learning the claimed invention but the claim scope, the history of the prior art, and the claimed invention’s place in it. Compared to many other examiner’s content in their much more specific box, my area is often much more complicated.

I love allowing applications (It’s actually one of my favorite parts of the job. I’m currently allowing my 3rd this bi-week!) and like to think I am a fair examiner, however, I think my allowance rate does not reflect my attitude toward allowance but more reflects the complexity and breadth of my art unit.

Mark Nowotarski

May 22, 2015 02:03 pmStay out of there if at all possible (which means drafting claims/specifications to avoid certain magic words).

Has anyone had any success getting a business method patent classified outside of business methods? If so, feel free to contact me through my web site if posting here is not appropriate.

Night Writer

May 22, 2015 12:49 pmI’ve had examiners tell me that the company I represent files too many law suits so they aren’t going to allow the case.

Curious

May 21, 2015 08:22 pmJNG:

A suggestion or two. Don’t bother appealing if you are going to go to appeal (unless your claims really need the help). Amendments raise estoppel issues and can allow the Examiner to go final on new prior art.

As a corollary to the “no amendment” advise is the don’t attempt to “compromise” with the Examiner at your own initiative. Instead, let the Examiner take the initiative when it comes to compromising.

The rest of your comments are spot on. Anybody who thinks it is easy to get a software or business method patent hasn’t attempted to get one. 3600 (business methods) is a black hole where patent applications go to die. Stay out of there if at all possible (which means drafting claims/specifications to avoid certain magic words).

JNG

May 21, 2015 12:13 pmI suspect if you poll patent practitioners with experience in these outlier groups you will find the same pattern:

1) do prior art search, craft claims to avoid best references

2) watch Examiner reject claims based on art worse than what you cited, using specious logic;

3) amend anyway because you can still get SOME coverage

4) watch Examiner “invent” another reason or reference to combine;

5) file appeal

6) file appeal brief

7) watch Examiner withdraw rejection, in favor of something he/she calls a “new” rejection, but which is really just the same logic/art repackaged;

8) amend again anyway to try and reach a compromise

9) watch compromise get rewarded with yet another random rejection

10) appeal again

repeat and recycle

the one Examiner I had allowed 7 out of 300 cases; he was proud of this, as he apparently perceives his “duty” as not allowing ANY cases that might bring attention to the PTO because some big company might be infringing – he was particularly proud that 6 of those 7 had come from the PTAB reversing him in favor of the applicant, so in reality, he had only “allowed” 1 case in 5 years

Look at the history for US Patent No. 8,630,960 for example; 10 YEARS of prosecution:

4 years to first Office Action

1.5 years of prosecution

file appeal

Examiner withdraws rejection, issues new one

1.5 more years of prosecution

file new appeal

wait 3+ years for decision reversing Examiner

But to hear from the anti-patent propaganda crowd, it’s so… “easy” to get SW patents.