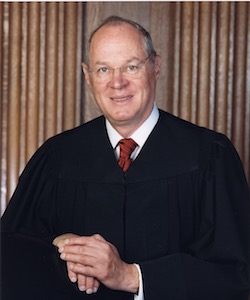

Yesterday the United States Supreme Court issued a decision in Commil USA, LLC v. Cisco Systems, Inc. The case dealt with the issue of induced infringement. Specifically, the issue considered by the Supreme Court was whether a good faith belief of patent invalidity is a defense to a claim of induced infringement. In a 6-2 decision written by Justice Kennedy, the Supreme Court ruled that belief of invalidity is not a defense to a claim of induced infringement. Justice Breyer took no part in the decision. Justice Scalia, who was joined by Chief Justice Roberts, dissented.

While it seems that the Supreme Court issued a reasonable decision in this case it is deeply troubling how little the Supreme Court actually knows about patent law. In addition to repeatedly discussing the validity of the Commil patent, rather than the validity of the patent claims, the Supreme Court also seemed to suggest that Cisco could have relied on a procedural challenge to the Commil patent that simply wasn’t available as an option at any relevant time during the proceedings. Thus, even when the Supreme Court issues a decision within the bounds of reasonableness they can’t help but evidence their lack of knowledge with respect to basic patent law concepts.

Historical Background

The history of this dispute dates back to 2007 when Commil, which makes and sells wireless networking equipment, sued Cisco in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas. Commil alleged that Cisco had directly infringed Commil’s patent under 35 U.S.C. 271(a) by making and using networking equipment. Commil also alleged that Cisco had induced others to infringe the patent under 35 U.S.C. 271(b) by selling the infringing equipment for them to use.

At the conclusion of the first trial the jury concluded that Commil’s patent was valid and that Cisco had directly infringed. The jury also found that Cisco was not liable for induced infringement. The jury awarded Commil $3.7 million in damages for direct infringement. At the conclusion of the trial Commil filed a motion for a new trial on induced infringement and damages, which the District Court granted.

One month before the start of the second trial Cisco filed a petition for reexamination of the Commil patent at the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). The USPTO granted Cisco’s request but ultimately confirmed the validity of Commil’s patent claims.

When the second trial proceeded Cisco raised a good faith defense to the claim of induced infringement, arguing that it had a good faith belief that Commil’s patent was invalid. As a result, Cisco argued that it could not be liable for induced infringement. To this end, Cisco sought to introduce evidence to support their asserted good faith belief of patent invalidity. The District Court ruled that Cisco’s proffered evidence of good faith belief of invalidity was inadmissible. Ultimately, on April 8, 2011, the jury returned a verdict in favor of Commil on induced infringement and awarded $63.7 million in damages.

Cisco appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. The Federal Circuit affirmed in part, vacated in part, and remanded for further proceedings. In an opinion by current Chief Judge Prost, the Federal Circuit concluded: “Cisco’s evidence of a good faith belief of invalidity may negate the requisite intent for induced infringement.” The Federal Circuit explained that the District Court erred by allowing the jury to find Cisco liable for induced infringement “based on mere negligence where knowledge is required.” This decision was not at issue at the Supreme Court.

The issue taken by the Supreme Court related to a separate, second holding of the Federal Circuit relating to Cisco’s contention that the trial court committed error by excluding Cisco’s evidence that it had a good faith belief that Commil’s patent was invalid. The Federal Circuit reasoned: “evidence of an accused inducer’s good faith belief of patent invalidity may negate the requisite intent for induced infringement.” Judge Newman dissented on that point. In Judge Newman’s view a good faith belief of patent invalidity is not a defense to induced infringement, which was the rule ultimately adopted by the Supreme Court.

SCOTUS Ruling on Induced Infringement

Justice Kennedy delivered the opinion of the Supreme Court, starting his substantive analysis with a discussion of direct infringement, which was joined by Justices Ginsburg, Alito, Sotomayor and Kagan. Justice Thomas, who joined in the majority with respect to Parts II-B and III, did not join the substantive background discussions. Although Justice Thomas did not file a separate opinion it seems that he did not join parts of the decision that were historical in nature (Part I) and those parts of the decision that related to substantive discussion of legal issues not being considered by the Court (Part II-A). Notwithstanding, Kennedy began by explaining that direct infringement is a strict liability offense, which means that the defendant’s state of mind is irrelevant. In contrast to direct infringement, however, liability for inducing infringement attaches only if the defendant both knew of the patent and that “the induced acts constitute patent infringement.”

Moving on to the issue at hand, regarding whether a good faith belief of patent invalidity is a defense to a claim of induced infringement, Kennedy explained: “[B]ecause infringement and validity are separate issues under the Act, belief regarding validity cannot negate the scienter required under §271(b).” Kennedy concluded: “Were this Court to interpret §271(b) as permitting a defense of belief in invalidity, it would conflate the issues of infringement and validity.”

Moving on to address the logical argument that an invalid patent cannot be infringed, Kennedy explained logic and semantics sometimes must give way to interpretation of an otherwise clear statutory framework. Kennedy wrote:

To say that an invalid patent cannot be infringed, or that someone cannot be induced to infringe an invalid patent, is in one sense a simple truth, both as a matter of logic and semantics. See M. Swift & Sons, Inc. v. W. H. Coe Mfg. Co., 102 F. 2d 391, 396 (CA1 1939). But the questions courts must address when interpreting and implementing the statutory framework require a determination of the procedures and sequences that the parties must follow to prove the act of wrongful inducement and any related issues of patent validity. “Validity and infringement are distinct issues, bearing different burdens, different presumptions, and different evidence.” 720 F. 3d, at 1374 (opinion of Newman, J.). To be sure, if at the end of the day, an act that would have been an infringement or an inducement to infringe pertains to a patent that is shown to be invalid, there is no patent to be infringed. But the allocation of the burden to persuade on these questions, and the timing for the presentations of the relevant arguments, are concerns of central relevance to the orderly administration of the patent system.

Kennedy also took the opportunity to explain the other avenues that Cisco could have taken if they had a good faith belief that the patent claims of the Commil patent were invalid. Citing the opportunity to file a declaratory judgment action, seek inter partes review at the USPTO, or filing a request for reexamination as Commil did, Kennedy wrote:

There are also practical reasons not to create a defense based on a good-faith belief in invalidity. First and foremost, accused inducers who believe a patent is invalid have various proper ways to obtain a ruling to that effect. They can file a declaratory judgment action asking a federal court to declare the patent invalid. See MedImmune, Inc. v. Genentech, Inc., 549 U. S. 118, 137 (2007). They can seek inter partes review at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board and receive a decision as to validity within 12 to 18 months. See §316. Or they can, as Cisco did here, seek ex parte reexamination of the patent by the Patent and Trademark Office. §302. And, of course, any accused infringer who believes the patent in suit is invalid may raise the affirmative defense of invalidity.

A portion of this explanation by Justice Kennedy seems a bit disingenuous, at least in this case. The ability to seek inter partes review (IPR) before the PTAB at the USPTO did not become an option until September 16, 2012, on the first anniversary of the signing of the America Invents Act (AIA). The second trial concluded with a jury verdict on April 8, 2011, which was more than five months before an IPR could have been filed. While it is true that an IPR can be filed to challenge any patent, there was no realistic opportunity for Cisco to file an IPR challenging the Commil patent claims.

[Varsity-1]

The Patent Troll Not in the Room

Once again the Supreme Court was mindful of patent licensing practices and abusive litigation tactics employed by so-called patent trolls. In the final section of the Supreme Court’s opinion Justice Kennedy wrote that the Court is mindful of abusive licensing practices, but that in this case the parties raised no issue of frivolity.

Notwithstanding, Justice Kennedy wrote that it is “necessary and proper to stress that district courts have the authority and responsibility” to stop the filing of frivolous patent infringement lawsuits. Citing to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 11, Kennedy explained that if frivolous cases are filed “it is within the power of the court to sanction attorneys for bringing such suits.” Kennedy also went on to reiterate that district courts now have broad discretion to award attorney’s fees to prevailing parties in exceptional cases, thanks to the Court’s 2014 ruling in Octane Fitness. Kennedy explained that the ability to rely on Rule 11 sanctions and discretion to award attorneys fees “militate in favor of maintaining the separation expressed throughout the Patent Act between infringement and validity.”

SCOTUS and the Invalid Patent

Time and time again throughout this decision Justice Kennedy addresses the validity of the Commil patent, which is why this article discusses the issue in those terms. Of course, a patent cannot be invalid. Still, discussion of whether the patent was properly believed to be invalid raises important questions. First, is the Supreme Court simply not being nuanced and merely using sloppy shorthand language? Second, is the Supreme Court envisioning some new defense whereby invalidity is not examined on a claim-by-claim basis, but rather on a patent-by-patent basis? Third, does the Supreme Court know enough about patent law to even be making any decision at all?

It is axiomatic that invalidity is an issue to be considered on a claim-by-claim basis. Indeed, if Cisco had prevailed during reexamination the patent would not have been declared invalid even if all claims had been invalidated. A patent without claims, which is admittedly useless, would have emerged from reexamination.

There is little evidence in this opinion that the Supreme Court is adopting a new view on invalidity whereby a patent could be invalidated in whole. It is, however, correct to observe that in recent patent eligibility decisions the Supreme Court has instructed courts to look past the claims and determine what the invention really is before ruling on patent eligibility. Ignoring the patent claims is a concerning trend in Supreme Court cases, which is why the failure to properly characterize invalidity as relating to patent claims and not to the entire patent is so troubling.

Taking issue with the Supreme Court discussing the invalidity of a patent rather than discussing the invalidity of patent claims may seem a minor point to some, but this is an important piece to a much larger narrative. The Supreme Court does not understand basic patent law and routinely makes numerous silly mistakes. If a law student taking a basic Patent Law 101 course were to discuss “validity of a patent” in a final exam they would be marked down for missing a nuance that is critical to substantive patent law. The Supreme Court, however, can make sloppy misstatements of law without any consequences. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court can make up patent law as they go along, which they increasingly do.

Discussing the validity of a patent rather than the validity of patent claims would perhaps be a minor matter not even worthy of mention, but Justice Kennedy and five other Supreme Court Justices suggest the filing of an inter partes review as a way to challenge patents (or patent claims) thought to be invalid. Was the Supreme Court really suggesting that Cisco should have filed an IPR after two jury trials on the issue of inducement had already concluded and while the case was pending on appeal to the Federal Circuit? Or did the Supreme Court simply not know that IPR wasn’t an option to challenge patent claims until September 16, 2012? Perhaps the Supreme Court was merely saying there is no reason to conflate validity with infringement given the myriad ways to now challenge a patent, but it is not clear that Cisco had standing to bring a declaratory judgment action, and they certainly could not have brought an IPR.

Regardless of whether the Supreme Court decided this case properly, it is abundantly clear that the Supreme Court is wholly unqualified to address even basic issues of patent law with the nuance necessary. Careless misstatements evidence a total lack of understanding, which creates uncertainty and confusion. Either the Supreme Court needs a remedial tutorial on patent law or they need to stop taking cases in an area where they seem to lack competence.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

14 comments so far.

Anon

May 30, 2015 09:46 am“ I think it is some of the older judges that have presented the biggest problems. Judges Dyk, Prost and Mayer”

and

“Prost is a miserable Chief Judge for the Federal Circuit. The loss of Rader in that position is really taking its toll the ability of the Federal Circuit to do battle”

are comments that are dead on.

Therein lies blame that cannot be shifted.

Contrast the champion of patent law Judge Rich who even after the Supreme Court yielded an enormous amount of dicta in the Benson case refused to be beaten down from what the patent law was written to accomplish. Having helped write the law, he knew more than any single person in the entire judiciary what the law meant. His unwillingness to be browbeaten by a “superior” court turned the tide and yielded Supreme Court decisions of Chakrabarty and Diehr. I truly had my hopes that Alice would mirror such reasoning, but I believe that without a champion below** to “keep the Royal Nine honest,” the Supreme Court had no compunction from messing with the wax nose of 101.

I now firmly think that the only clear path forward, the only way to eliminate judicial re-writing of patent law, is for Congress to be explicit about the limits of Judicial reach. Perhaps O’Malley senses this (she can be very astute).

Since patent appeals are not a matter of original jurisdiction for the Supreme Court, it is within the Constitutional power of Congress to remove review from the Supreme Court (as long as some Article III court still has review power – See Marbury. Unfortunately, as Gene and others point out, the body set up by Congress with an explicit direction to bring clarity to patent law has been compromised due to the higher judicial influence, a reconstitution and re-dedication of a new body may be what it required to restore a proper respect for patents and patent law in our society.

**I think that even before Rader’s exit under unfortunate circumstances, his penned opinion in Alice waived a flag of regrettable surrender. I believe he knew that he could not lead those who would only kowtow to the imposition of judicial rewriting of patent law.

EG

May 29, 2015 09:19 am“I see the current state of affairs at the Fed. Cir. as abysmal.”

Night Writer,

I hear you. In particular, from what I’ve seen so far, Prost is a miserable Chief Judge for the Federal Circuit. The loss of Rader in that position is really taking its toll the ability of the Federal Circuit to do battle with the Royal Nine, which they really need to do before the Royal Nine completely muck up our patent law jurisprudence.

Night Writer

May 28, 2015 11:13 pmThanks Edward. I think you summed up the case very well.

Night Writer

May 28, 2015 11:13 pmTaranto, Hughes, Reyna are the ones that I have found to be the problem judges appointed by Obama. All three appear to come in the wake of the great influence of corporate money from Google and the like.

I agree that not all is bad from Obama. Kara Stoll may be decent. But, she is the Rader replacement so I think Obama realized that if appointed yet another anti-patent non-science judge that there may a revolt.

Chen I think was a surprise. He was very anti-patent at the PTO, but I think he tends to try to stick to applying the law and realistically representing technology and science. That sets him far apart from most of the judges. My problem with judges like Taranto is that they don’t have science backgrounds. I remember one opinion by Taranto where he wrote something to the effect the mere computer implementation of human thought. At the same time European scientist were objecting to trying to simulate human thought as being too difficult. They said science had not advanced far enough to spend so much money attempting to simulate the human brain. Taranto has no foundation to understand these issues and generally appears to be trying to limit patents through judicial activism.

To my mind those three (Taranto, Hughes, and Reyna) are Google judges. We’ll see if they break away from that, but I think they were appointed under the direction of Google just like Lee.

To my mind the problem is that the judges as a whole at the Fed.Cir. don’t have the gravitas to stand up to the SCOTUS. I suspect the SCOTUS is very aware that they were appointed under the guidance of Google.

And, not only that but few if any of these judges have any real world experience of working with start-ups or big corporations in their innovation divisions and doing real patent law. They simply have no way to take the measure of what anything means. I classify most of what they say as disassociated cognition.

The other issue is that they don’t seem to understand the basics of patent law and don’t seem to care. They consistently refuse to interpret claims as one skilled in the art would in light of specification. They speak of “purely functional” claims, which I have yet to see one of those. They buy Lemley’s nonsense hook, line, and sinker–or they know it is nonsense and see it as a great way to limit patents.

Anyway, on a case by case basis, I see the current state of affairs at the Fed. Cir. as abysmal.

Edward Heller

May 28, 2015 02:50 pmStep Back, one can be liable for inducing copyright infringement even if one does not know that the acts induced constitute infringement.

Also, see the brief of the law professors that pointed out that “[o]pinions from the Supreme Court and lower courts from the mid-19th century through the passage of the 1952 Act repeatedly held that aiding and abetting direct patent infringement solely required specific intent merely to further the acts that constituted direct infringement, and did not require knowledge of the patent-in-suit. Because Congress codified this precedent, the Supreme Court should not find that Section 271(b) requires the inducer to know of the applicable patent.

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1734376

.

Gene Quinn

May 28, 2015 02:12 pmNight Writer-

I suppose you are correct about Obama’s appointments to the CAFC, although there is a patent person (Kara Stoll) who has cleared the Senate Judiciary Committee. She was a former patent examiner and current partner at Finnegan. Ray Chen was also a patent person and an EE. O’Malley and Wallach were district court judges, but they had quite a good bit of experience having sat on patent cases. Reyna was at least an IP attorney with business law experience. The one appointment that really seemed strange was Hughes, who had no particular knowledge or association with patents. He even said during his hearing that he would study up on patent law.

Perhaps Hughes will turn out to be an excellent judge. There was little in Judge Michel’s background to suggest he would become a leading patent jurist. But I think Obama’s appointments to the CAFC have been largely good. 2 patent people and 2 district court judges with real experience managing a trial seems appropriate to me. I think it is some of the older judges that have presented the biggest problems. Judges Dyk, Prost and Mayer have seemed to be particularly on the side of weaker patent rights, and Judge Lourie seems to have given up the 101 fight altogether.

-Gene

step back

May 28, 2015 01:29 pmIsn’t there some analogous basis in criminal law, where one believes they are not committing a crime and yet they are? (Not to be confused with the other case where one believes they ARE committing a crime event though physically it is not possible i.e. shooting a dead person which is an attempted crime.)

Night Writer

May 28, 2015 12:45 pmGene says: >>>Still, some of the decisions of the Federal Circuit practically beg to be reversed, as if they were written to achieve the clearly wrong answer on a test. Thus, the Federal Circuit is at least partly to blame.

Or is it the president for appointing unqualified people to the Fed. Cir.? Obama has appointed more judges that have no science background and no patent law background than judges that have some background in science and patent law.

Saint Cad

May 27, 2015 10:15 pmI think SCOTUS got it right but expressed it in their usual clueless way. Once the USPTO decides the claims are valid, the assumption is they are valid except if they are ruled by a court or the USPTO, upon re-examination, to be invalid. Since Cisco’s good-faith evidence was not allowed in District Court and no reason given by the court as to why it was excluded, it is hard to say what they based their infringement on but SCOTUS is right in that there are ways to do that other than “I honestly thought it was invalid”.

Edward Heller

May 27, 2015 09:45 pmGene, both 154 and 271 give the inventor the exclusive right to make, use or sell, etc. the patented invention. To prove infringement, one must prove that one or more claims read on an accused device, but legally, there is only one invention and only one royalty regardless of the number of claims proven to be infringed.

282 speaks that a patent is presumed valid. Claims in addition are individually presumed valid. But the statute does say that one can prove a patent invalid. Not having the right inventors is one such way.

The reason for multiple claims is that some claims might be too broad and run into prior art. Many claims also have too many unnecessary limitations. But legally, there is really only one invention.

So, I don’t think the Supreme Court does not get it on this issue.

Secondly, did you read the government brief? It explains that “knowledge of infringement” only required that the patentee give notice in some manner of what the patentee believed was infringement. That was the fact pattern in Global-Tech through marking. Everything else in Global-Tech beyond that was dicta.

Thus, it was not clear that a private belief by the infringer that what he or she induced was not infringement was implicit in Global-Tech’s facts.

The Supreme Court rejected the government’s argument. But the government was right.

The consequence of being able to avoid liability based on a private, albeit, reasonable, belief is profound. It really does eviscerate both inducement and contributory infringement because a non-infringement opinion may be obtained in most cases. As well, in my experience, most lawsuits involve claim construction disputes that are not frivolous and are dispositive on infringement. In either case, the putative infringer is now off the hook on inducement or contributory infringement.

Gene Quinn

May 27, 2015 09:18 pmEG-

As you know, the Federal Circuit was created because Congress didn’t like the mockery the Supreme Court had made out of patent law. They left patent law well enough alone for a generation. They should stay out of patent law moving forward.

Still, some of the decisions of the Federal Circuit practically beg to be reversed, as if they were written to achieve the clearly wrong answer on a test. Thus, the Federal Circuit is at least partly to blame.

-Gene

Gene Quinn

May 27, 2015 09:16 pmEdward-

Not sure what you are talking about with respect to there being only one royalty and why that might matter. The Supreme Court is certainly not correct when they talk about a patent being infringed. Patents are not infringed. Patent claims can be infringed, but a patent in and of itself cannot be infringed. This nuance is important particularly given Supreme Court precedent in recent cases where the Court says it is appropriate to ignore the claims and look to the invention disclosed for purposes of a 101 analysis.

I’m also not clear on the hair you are trying to split when you say that now you “have to prove that the defendant knew that direct infringement was actual patent infringement.” Direct infringement would be patent infringement.

Further, what you say is new law isn’t new law at all. In in Global-Tech Appliances, Inc. v. SEB S.A., 131 S. Ct. 2060 (2011) the Supreme Court held that induced infringement “requires knowledge that the induced acts consti- tute patent infringement.” The knowledge requirement of Global-Tech may be satisfied by showing actual knowledge or willful blindness. So this decision does not change the law or place any additional burdens on patent owners.

-Gene

Edward Heller

May 27, 2015 04:57 pmGene, in a sense, the Supreme Court is right. Regardless of the number of claims held infringed, there is only one royalty.

I think you missed the main problem with the opinion, the part not joined by Thomas and which was not entirely historical. It is the rejection of the position of the government that the only knowledge that was required to be proved was that the patent owner contended that the products accused of indirect infringement infringed. Now, because of this opinion, we have to prove that the defendant knew that direct infringement was actually patent infringement. A reasonable belief of noninfringement is sufficient to avoid liability. Obviously this opinion extends to contributory infringement.

This formulation all but removes both inducement and contributory infringement as patent remedies because of the virtual impossibility of proving the “knowledge of infringement” requirement given that any reasonable position on noninfringement provides an excuse from liability. We all know just how easy it is to get noninfringement positions opinions from patent law firms. As well, every patent infringement suit involves claim construction disputes that affect infringement and at least some of them can be reasonable. In either case, the defendant is excused from liability and the patent owner may not only be facing a loss, but might end of paying the defendant’s attorney fees if they knew of the defendant’s position on infringement and proceeded anyway.

EG

May 27, 2015 02:40 pm“In the final section of the Supreme Court’s opinion Justice Kennedy wrote that the Court is mindful of abusive licensing practices, but that in this case the parties raised no issue of frivolity.”

Gene,

I would have been fine with Kennedy’s majority opinion but for Part III which harkens back to his concurring opinion in eBay. Sigh. You’re correct, the Royal Nine is thoroughly unqualified, both on the science/technology, as well as the patent law to rule in such cases. Like the CCPA in its early stages, there should be no ability to appeal/petition for certiorari to SCOTUS in patent cases unless constitutional issues are REALLY involved.