The technological innovations developed by Google, Inc. (NASDAQ:GOOG) tend to raise some uneasiness in certain consumers groups. Some have noted unusual results for Google Map searches, including one British journalist who discovered that a Google Map search of his own name returned a pub that he frequented. Others were spooked to discover searches of their own name bringing up restaurants they’ve visited or even their current location. Google has also developed auto-reply technology for emails and text messages which would mine personal information to determine which messages a person would typically respond to and draft a suggested reply. As has been suggested in this article by Forbes, there are those who recoil at the thought of a computer being able to reverse engineer their own personal correspondence.

The technological innovations developed by Google, Inc. (NASDAQ:GOOG) tend to raise some uneasiness in certain consumers groups. Some have noted unusual results for Google Map searches, including one British journalist who discovered that a Google Map search of his own name returned a pub that he frequented. Others were spooked to discover searches of their own name bringing up restaurants they’ve visited or even their current location. Google has also developed auto-reply technology for emails and text messages which would mine personal information to determine which messages a person would typically respond to and draft a suggested reply. As has been suggested in this article by Forbes, there are those who recoil at the thought of a computer being able to reverse engineer their own personal correspondence.

Most recently, the mainstream media has been aflame over a recently unveiled Google innovation which poses an Orwellian challenge to family privacy in the eyes of some critics. A patent application published May 21st by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office describes a smart toy developed by Google which can respond to a child’s voice or gestures. As if comparing the personally responsive electronic doll to the infamous “Chucky” doll of the Child’s Play horror movie saga wasn’t bad enough, some have been raising a red flag as to whether the camera and microphone components of this Google toy constitute a serious privacy threat.

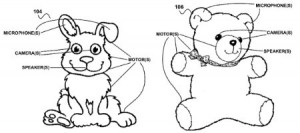

The children’s toy in question is explained by U.S. Patent Application No. 20150138333, entitled Agent Interfaces for Interactive Electronics that Support Social Cues. It should be pointed out that no patent has actually been issued for this technology yet, which has been erroneously reported by many of the news publications linked above. Filed in February 2012, the patent application discloses a method involving an anthropomorphic device containing a camera and a microphone detecting a social cue, such as a person’s gaze directed towards the device. The anthropomorphic device aims the camera and microphone in the direction of the gaze, receives an audio signal through the microphone, transmits a command to a media device based on the audio signal and provides an acknowledgement of the received audio signal.

The children’s toy in question is explained by U.S. Patent Application No. 20150138333, entitled Agent Interfaces for Interactive Electronics that Support Social Cues. It should be pointed out that no patent has actually been issued for this technology yet, which has been erroneously reported by many of the news publications linked above. Filed in February 2012, the patent application discloses a method involving an anthropomorphic device containing a camera and a microphone detecting a social cue, such as a person’s gaze directed towards the device. The anthropomorphic device aims the camera and microphone in the direction of the gaze, receives an audio signal through the microphone, transmits a command to a media device based on the audio signal and provides an acknowledgement of the received audio signal.

Some of the creep factor inspired by this invention might simply be the result of Google’s ability to create products which naturally ingratiate themselves with users. For instance, the patent application cites the benefits of the anthropomorphic device taking on a “cute” and “toy-like” form, specifically where it comes to attracting the attention of young children. Of course, ask any toy developer and that person would have to tell you that he or she is trying to achieve the same effect with their products.

But then why collect data from children? For one reason, it’s necessary for the product to have any meaningful use. The patent application very specifically claims an anthropomorphic device that transmits a command to an external media device based on an audio signal received by the device’s microphone. If the device did nothing but respond to the gaze of a young child by turning its head, it wouldn’t be much more than a glorified Teddy Ruxpin.

Let’s consider one benevolent application of this technology, should it ever come to market, that doesn’t involve anything skin-crawling: The parents of a young child purchase this Google doll, which could be formed as a rabbit or a Teddy bear according to diagrams attached to the patent, for their child. The doll functions as a baby monitor which can interact with a child whether or not the child is fully able to verbally communicate what it wants. If the child wanted to watch a favorite television program, all he or she would have to do is blurt out the name of the program and a command to play on-demand video of that program could be transmitted to a Internet-enabled TV set. Alternatively, if the child was in distress, a notification could be sent directly to a parent’s smartphone. These specific functions aren’t mentioned in the patent description but it seems fairly obvious given the system protected by the patent.

We don’t need to consider any malicious uses of this technology, however, we do realize that a serious privacy risk does exist with such a product. Some parents may be familiar with the legal actions taken by the Federal Trade Commission against electronics developer TRENDnet, whose SecurView cameras for home security and baby monitoring were easily hacked by intruders wanting to view video feeds that were marketed by TRENDnet as being secure. The FTC has been beating the drum recently over the potential privacy abuses of the growing Internet of Things sector and the prospects of “smart home hacking.” Here at IPWatchdog, we’ve discussed unsavory data mining practices in which the ridesharing service Uber is engaged, a practice which has likely proven to be very profitable for the company. The issue seems to be that we, as consumers, love the information services of the digital age but at the same time we’re incredibly wary of the unintended uses of that data we create.

Much of our society’s contemporary distrust of technology can be seen in the public and political debates surrounding the National Security Agency. This governmental organization has been decried by electronics industry groups and a sizable chunk of the American populace for telecommunications surveillance programs that many believe are an improper intrusion of citizen privacy. The agency is in the spotlight this week as Congress decides whether to reauthorize certain sections of the 2001 Patriot Act, especially Section 215 which governs the NSA’s ability to conduct its surveillance programs. Without reauthorization, provisions of the Patriot Act will end on Monday, June 1st.

President Obama has been pushing for the reauthorization of the NSA’s surveillance programs, calling many of the aspects of those programs “noncontroversial.” Opposition to the NSA reauthorization has come from both parties of Congress with politicians like Sens. Patrick Leahy (D-VT) and Rand Paul (R-KY) lending their respective voices to the anti-NSA surveillance crowd. Pres. Obama and other members of Capitol Hill have sought to find some middle ground through the development of the USA FREEDOM Act, a bill with a hopelessly long acronym title that would establish a framework for the collection of call detail records and require that those records be tied to a current investigation, making the collection of telephone records much more targeted. Passage of the USA FREEDOM Act would leave many provisions of Section 215 of the Patriot Act in place.

Many of our readers might remember an American statesman, popular enough in his own time to win four presidential elections, who once told the entire country that “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” There are those who feel confident that the same is true of this debate, as far as the NSA’s surveillance program goes. Some have pointed out that the metadata pertaining to calling records that are collected by the NSA do not convey as much sensitive personal information as websites such as whitepages.com. Further, the federal government is governed by the Fourth Amendment in such matters, providing a layer of data privacy which is not required of private entities like Google. Finally, for all of the opinion pieces and allegations of data malfeasance that pop up in the media, there seem to be remarkably few stories about actual criminal activities stemming from these data surveillance practices, aside from the data intrusion issue itself.

In the world of consumer electronics, there may also be reasons to keep calm and carry on despite the creep factor inspired by technologies that see and listen to their users. Many products require the use of a trigger word or phrase to initiate any data collection and transmission procedures. Again, consumers should always be on alert in case they’re suspicious of data collection practices, but if a person only activates a handset’s voice recognition technology in order to locate misplaced electronics, that technology is only going to know when a user is looking for his or her cell phone; it won’t know or be interested in the fact that its user might be plotting a criminal act.

We’ve documented a significant rise in patent applications filed by companies across the globe in the sector of cellular privacy here on IPWatchdog. It seems obvious that many value the protection of personal data and the value of those technologies is increasing with the growing size of the wearable gadget and Internet of Things markets. Popular culture will probably always retain some sense of the fears inspired by tech gone awry, most recently evidenced in the motion picture release of the horror movie Unfriended. How we choose to personally respond to those fears is entirely up to us.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

No comments yet.