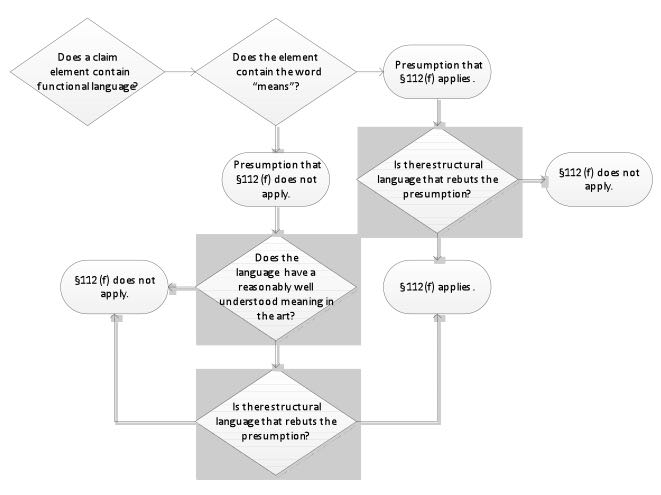

In Williamson v. Citrix,[1] the Federal Circuit overruled its own precedent that there is a “strong” presumption that claim limitations that do not use the term “means” are not means-plus-function limitations. This change has been decried by practitioners who purposefully avoid the word “means” in order to avoid means-plus-function treatment of their functionally claimed elements.

What do you accomplish by avoiding means-plus-function treatment? Under 35 U.S.C. 112(f),[2] means-plus-function elements are “construed to cover the corresponding structure . . . described in the specification and equivalents thereof.” Is it reasonable to expect that a “means”-less functional element would be construed to be broader than provided in §112(f)? No. Claims are, and always have been, limited the scope of the written description and the enabling disclosure in the specification. There is a risk that by not limiting a claim to what is disclosed in the specification and equivalents thereto, the claim will be found invalid.

In Halliburton Oil Well Cementing Co. v. Walker,[3] the Supreme Court construed claims directed to operating a pump in an oil well. The claims at issue required:

Means associated with said pressure responsive device for tuning said receiving means to the frequency of echoes from the tubing collars of said tubing section to clearly distinguish the echoes of said couplings from each other.

Among the things that concerned the Supreme Court about this claim language was that “[n]either in the specification, the drawing, nor in the claims here under consideration, was there any indication that the patentee contemplated any specific structural alternative for the [disclosed] acoustical resonator or for the resonator’s relationship to the other parts of the machine.”[4] The Supreme Court said that “[u]nder these circumstances the broadness, ambiguity, and overhanging threat of the functional claim of Walker became apparent.”[5] Noting that Walker was claiming that “any device heretofore or hereafter invented” that performed the function infringed, the Supreme Court said “[j]ust how many different devices there are of various kinds and characters . . . we do not know.”[6] As a result, the Supreme Court held that that claims were invalid, noting that “to be consistent with [the precursor of §112], a patentee cannot obtain greater coverage by failing to describe his invention than by describing it as the statute commands.”[7]

A few years later, when Congress was revising the patent laws, it included the precursor of §112(f) on means-plus-function claiming, at least partly in response to Walker.[8] However, the innovation of §112(f) was that means-plus-function language could be employed at the exact point of novelty, as suggested in In re Donaldson,[9] while the limitation of the scope of such claims to what was validly supported by the specification preserved their validity.

While a “means”-less functional claim element may be broader in scope than a corresponding means-plus-function element, to the extent that this breadth exceeds what is supported by the specification, it is illusory. Thus, by eliminating the strong presumption that a “means”-less functional claim is not covered by §112(f), the Federal Circuit in Williamson v. Citrix may have eliminated what, in at least some circumstances, is a strong presumption that the claims are invalid.

After Williamson v. Citrix, there remains a presumption that “means”-less functional claims are not covered by §112(f), but is this a presumption of invalidity? Yes, when the functional language is broader than is supported by the specification, which it almost certainly is. However, there is a narrow category of “means”-less functional language, identified by the Federal Circuit in cases like Greenberg v.Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc.,[10] that does not invoke §112(f), and yet are validly limited to structure.

In Greenberg, the claim language at issue required “a cooperating detent mechanism defining the conjoint rotation of said shafts in predetermined intervals[.]”[11] Although the district court found this functional language invoked §112(f), the Federal Circuit disagreed. To the Federal Circuit, the fact that a particular mechanism is defined in functional terms was not sufficient to convert the language into a means-plus-function element under §112(f). The Federal Circuit found that “detent” was no different than many other terms that take their names from the functions they perform, such as “brake,” “clamp,” or “screwdriver.” The Federal Circuit noted that although these terms do not call to mind single, well-defined structures, they have a “reasonably well understood meaning in the art.”[12]

On the other hand, in cases like Welker Bearing Co. v. PHD, Inc.,[13] where the functional language employs verbal constructs or “nonce words” that are not recognized as the name of a structure, then §112(f) applies. Examples of such terms include “module for,” “mechanism for,” “device for,” “unit for,” “component for,” “element for,” “member for,” “apparatus for,” “machine for,” and “system for.”

Means-plus-function claiming is an opportunity to be embraced, not a trap to be avoided. Invoking §112(f) and the associated scope of a means-plus-function limitation is largely in the control of the patent drafter. Means-plus-function claiming offers several benefits, including convenience, the elimination of disclosure/dedication problems,[14] and the preservation some measure of equivalents, even in the face of prosecution history estoppel. Using a means-plus-function limitation under §112(f) allows the drafter to claim everything disclosed in the specification and equivalents thereto. Relying instead on expansive functional language in the claims may create a broader scope, but the protection is illusory if that scope is not supported by the specification.

§112(f) is a savings provision, protecting functional claim language from being invalidated for exceeding the scope of the disclosure. The Federal Circuit’s decision in Williamson v. Citrix, eliminating the strong presumption against the application of §112(f), makes this savings provision more readily available for claims with functional language.

______________________________

[1] Williamson v. Citrix Online, LLC., No. 2013-1130 (Fed. Cir. June 16, 2015) (en banc).

[2] For continuity purposes § 112, para. 6 and § 112(f) are referred to interchangeably.

[3] 329 U.S. 1 (1946).

[4] Id. at 11.

[5] Id. at 12.

[6] Id.

[7] Id. at 13.

[8] See, e.g., In re Fuetterer, 319 F.2d 259, 264 n.11, 138 U.S.P.Q. 217, 222 n.11 (C.C.P.A. 1963); In re Donaldson, 16 F.3d 1189, 29 U.S.P.Q. 2d 1845, 1849 (Fed. Cir. 1994).

[9] 16 F.3d at 1194, 29 U.S.P.Q. 2d at 1849.

[10] 91 F.3d 1580 (Fed. Cir. 1996).

[11] Id. at 1582 (quoting Claim 1 of the patent at issue) (emphasis added).

[12] Id. at 1583.

[13] 550 F.3d 1090 (Fed. Cir. 2008).

[14] Johnson & Johnston Assocs., Inc. v. R.E.Serv. Co., 285 F.3d 1046 (Fed. Cir. 2002).

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

6 comments so far.

Night Writer

July 29, 2015 10:04 amThis article is dead wrong. First, for EE/CS real engineers describe sets of solutions using functional language. That is how the art is practiced. This is a change (and it occurs a lot in the mechanical arts too) because of the innumerable solutions that have been found for so many problems. Introductory books will state clearly and unambiguously that functional language is meant to represent sets of solutions.

Deal with that in your article. I am very sick of the judicial activist just burning down the system without dealing with reality. So, respectfully, Mr. Wheelock deal with that FACT. Get that that is a FACT. Deal with it in your article.

Anon

July 29, 2015 07:22 amThere are some serious flaws in the understanding of 112(f) in this article from an historical basis as well as from a semantics or logical view.

I suggest that a more thorough reading of Federico’s commentaries would be helpful, paying attention to his tone as well as his words. The introduction of his work states that he is including his opinions on certain matters, and this is clearly so with the section of 112.

Congress opened up the use of functional language and did not constrain such use to 112(f) alone.

The attempt to reinvigorate “point of novelty” as that term is being used here should be rejected as simply not comporting with the law as written by Congress in 1952. Federico laments the actions of Congress in this regards and presages a counter move by the Court.

Whether or not such a counter move is supported legally by our structure of government is quite a different matter.

But Federico does not deny what Congress had done. The use of terms sounding in function exists beyond just 112(f) – as provided by Congress.

In any “true” combination claim, the so-called “point of novelty” is necessarily the claim as a whole. It is only with “single means” claims that the “point of novelty” argument has any breath left. This is very much why method claims have caused so much consternation (especially to certain rather vocal advocates of particular views of patent law). Most any method claim is easily divisible into multiple steps. This translates into easily avoiding the “single means” constraint left by Congress, and enjoying the extensive re-invigoration that Congress enacted in 1952.

It is important, critically important, to stress this point: 112(f) is concerned with purely functional claiming. The words of Congress enables a vast use of non-purely functional claiming outside of 112(f).

The author here is far too glib and overlooks this distinction. The hunt for “one and only one” objective physical object to match any partial functional claim is a fallacious one, as such is simply not what the law provides – and never has.

Yes, history does show that the Court had attempted to curb this reach. The Court has its political views on what patent law should be. But Congress reacted against that mindset in a clear and most definite manner. Our structure of government does not provide for the judiciary to control and to write patent law. Respect for the rule of law includes, and must include, a proper historical understanding of this past battle. When those who practice law and those who teach law forget about its history, well, we end up repeating battles that should be avoided.

David Stein

July 28, 2015 04:14 pm> I still love Judge’s Wallach’s comment regarding 35 USC 112 that we may now steer by the bright star of “reasonable certainty” rather that the unreliable compass of “insolubly ambiguity.” One of my all-time favorite lines — there is just so much packed into that single statement.

Hear, hear. It’s much-repeated these days in many contexts. Scalia is no doubt envious that he didn’t write it.

> I’ve come to the conclusion that many (most?) judges just don’t like patents.

There’s a definite anti-patent tilt over the last several years: KSR, Bilski, Mayo, Alice, Williamson, eBay, Biosig – as well as new post-grant opportunities for patent invalidation, the PTO’s increasing inclination to involve third parties in examination, and patentee-hostile rules about patent term extension… and still further patentee-hostile changes under consideration, such as fee shifting and real-party-in-interest…

At a recent conference, I had an opportunity to present some questions to a panel of PTAB judges. I noted this trend, and its disproportionate impact on small applicants such as sole inventors and startups, and asked whether there were any signs of hope for patentees to balance this trend.

The answer from the panel: “We don’t agree that there is such a trend. But as for signs of hope… well, um… there’s Therasense.”

Did not inspire confidence.

Curious

July 28, 2015 03:21 pmuntil the courts reach some semblance of consistency

LOL … 35 USC 101 hasn’t changed in something like 60+ years and no one (outside certain patent trolls on the “O” website) can say for certain what is patent eligible these days.

35 USC 103? Under KSR, who knows? If you know what “magic words” to invoke at the USPTO, almost anything is obvious.

I still love Judge’s Wallach’s comment regarding 35 USC 112 that we may now steer by the bright star of “reasonable certainty” rather that the unreliable compass of “insolubly ambiguity.” One of my all-time favorite lines — there is just so much packed into that single statement.

I’ve come to the conclusion that many (most?) judges just don’t like patents. I have my guesses why, but I’ll share that another time.

Curious

July 28, 2015 03:09 pmMeans-plus-function claiming is an opportunity to be embraced, not a trap to be avoided.

Yuck. I get rid of MPF language in claims wherever I find it. There have been way too many Court decisions that make MPF language traps for the unwary — a problem that has existed at least for a decade or two.

David Stein

July 28, 2015 03:02 pmI must respectfully disagree with this article on two key points.

First, regarding this:

> Is it reasonable to expect that a “means”-less functional element would be construed to be broader than provided in §112(f)? No. Claims are, and always have been, limited the scope of the written description and the enabling disclosure in the specification. There is a risk that by not limiting a claim to what is disclosed in the specification and equivalents thereto, the claim will be found invalid.

The obvious answer to the above question is: yes. There is an important distinction between claims that are limited to what the specification supports in a written-description or enablement sense, and claims that are limited to the specific embodiments disclosed and their (doctrine-of) equivalents.

Example:

“The invention comprises a machine comprising an operative combination of a widget and a gizmo. These components could be operatively coupled through physical fastening, using any physical mechanism that enables the widget and the gizmo to interoperate as shown in Fig. 1. Examples include: a screw, a nail, and a rubber band. However, any mechanism that physically fastens the widget and the gizmo is sufficient. We claim: a widget, a gizmo, and a fastener that physically fastens the widget to the gizmo.”

There is a key difference between the 112(f) and the non-112(f) construction of the term “fastener” in this claim. What if a competitor uses Velcro, or magnets, or an adhesive? Certainly, both constructions are limited to what the specification supports; but 112(f) is more narrowly restricted to the listed examples that does not covert these creative alternatives.

The non-“illusory” nature of this distinction is illustrated by the fact that this dispute exists at all! If the distinction in scope of 112(f) and non-112(f) is indeed “illusory,” then it would not be a significant topic of debate. The spate of recent cases, including Williamson, suggests otherwise.

Second, regarding this:

> Invoking §112(f) and the associated scope of a means-plus-function limitation is largely in the control of the patent drafter.

One would hope this to be the case, given the choice between using or not using the term: “means.” However, the modifications made in recent case law belies this measure of control.

On the one hand, in Williamson, the patentee explicitly chose not to describe its element as a “means” – instead using the term “module” – and the Federal Circuit nonetheless dragged it into 112(f) land, where it could then be invalidated under 112(b) because the specification failed to support a (wholly unintended!) means-plus-function construction.

On the other hand – one week later, in Lighting Ballast v. Philips Electronics, the patentee explicitly used the term “voltage source means” (which the claim defines as: “providing a constant or variable magnitude DC voltage between the DC input terminals”). The patentee denied the implication of this term, and, astonishingly, the Federal Circuit agreed. To make matters worse, the Federal Circuit reached this conclusion by stating that the term “voltage source means” connoted a specific structure in the prior art – and yet, the Federal Circuit then describes this “structure” as: “any device which converts alternating current to direct current, or other structure capable of supplying useable voltage to the device.”

This area is completely out of control – and is no longer within the control of the applicant – until the courts reach some semblance of consistency.