As of 2012, there were 34 million Americans and 71 million people worldwide who wore the thin film inserts known as contact lenses over their eyes for some form of vision enhancement, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. About 80 percent of those who sport contact lenses on a regular basis prefer the soft lens variety which has only been available in America for the past few decades. However, the history of the contact lens goes back more than 500 years and involves some individuals whose various achievements extend beyond the world of optometry and have helped to shape Western culture as we know it.

As of 2012, there were 34 million Americans and 71 million people worldwide who wore the thin film inserts known as contact lenses over their eyes for some form of vision enhancement, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. About 80 percent of those who sport contact lenses on a regular basis prefer the soft lens variety which has only been available in America for the past few decades. However, the history of the contact lens goes back more than 500 years and involves some individuals whose various achievements extend beyond the world of optometry and have helped to shape Western culture as we know it.

Over the course of the Companies We Follow series we run here on IPWatchdog, we’ve profiled a growing list of contact lens technologies coming out of the research and development activities of Johnson & Johnson (NYSE:JNJ) of New Brunswick, NJ. We’ve noted a rise in contact lenses which include electronic components that can change the color of a wearer’s iris, provide enhanced vision correction or project text and images directly over a wearer’s eye. The story of contact lens development since their conception in the earliest parts of the 16th century shows how an innovation can be perfected over the course of centuries to become a useful tool for helping many of the 50 percent of Americans who need vision correction.

Da Vinci and Descartes Factor Into the Early Days of Contact Lenses

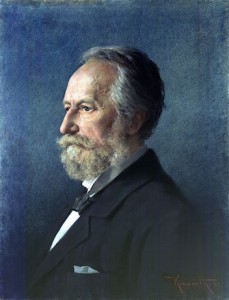

Any story about innovation that starts with Leonardo da Vinci is one worth telling. The fact that the great French philosopher René Descartes also plays a starring role in the history of the contact lens makes this story of innovation all the more noteworthy.

Eyeglasses worn to provide vision correction for wearer’s with eyesight issues had been around for a couple hundred years by the time that Leonardo da Vinci, perhaps the most important figure of the Italian Renaissance period, first posited that the cornea’s refractive, or light-bending, capabilities could be altered by placing the eye within a water-filled glass. This theory, put forward in Da Vinci’s 1508 publication Codex of the Eye, Manual D, was the first to recognize that the refractive quality of the human cornea could be manipulated.

Early versions of this concept of corrective vision, which typically required submerging the eyes in water contained within a glass, were cumbersome in practice. Leonardo described two applications of his discovery, one a glass bowl filled with water into which a person could sink their face, the other a glass hemisphere filled with water and worn directly over the eye. Much like Da Vinci’s aerial screw, which presaged the development of the modern helicopter, his water glasses would serve as the foundation for innovative developments that would take place many generations into the future.

The next tentative steps towards the development of the modern contact lens would take place during the 1630s by another man widely regarded to be one of the greatest minds of his century. Rene Descartes, the French philosopher who gave the world Cartesian doubt and the phrase “I think therefore I am,” published a medical treatise in 1636 which conceived of a lens placed directly over the eye. Attached to the lens was a long tube filled with water, expanding upon Da Vinci’s earlier water-based concepts. Impracticalities existed with the Descartes lens as well, as the glass tube holding the water prevented the user from blinking. Descartes was the first to realize that the eye’s cornea and not the sclera, or the white portion of the eye, was the only site of the eye where light refractive manipulation was useful for vision correction.

By the time the world was presented with a lens that could be worn directly over the eye for a period of time, water was left out of the equation and we were left with a glass insert worn on the eye. If that sounds horribly uncomfortable to any of our readers, they would be right. Glass lens inserts were constructed to cover both the cornea and the sclera, preventing the eyes from receiving the oxygen they need and resulting in corneal swelling. Early glass contact lens models would become painful for wearers within 30 minutes after a person put on a pair.

British physicist John Herschel took the world in that direction in 1827 when he proposed correcting an irregular cornea through the use of a glass capsule filled with animal jelly. It wouldn’t be until the 1880s that glassmaking techniques advanced to the point that lens could be crafted to match the natural curvature of the eye. Perhaps the first true contact lenses were created by Swiss physicist A.E. Fick in 1888, when the lens maker fabricated a spherical glass segment for the correction of refractive errors in a wearer’s eyes. During that same year, French optician Eduoard Kalt also created fitted glass lenses to correct vision issues stemming from the cornea.

More Comfortable Plastics Give Way to Today’s Hydrogel Lenses

Glass lenses didn’t simply cut off the flow of oxygen to a wearer’s eyes, although that could cause enough discomfort as it was. Most lenses were too heavy to sit reliably on top of the eye and the glass could be affected by tears. In addition, glass has a natural fragility that makes it a risky proposition for use directly over the eye.

The 1930s saw the first contact lenses constructed from plastic materials, which allowed greater flexibility, durability and remained upon the wearer’s cornea for a longer period of time. In 1936, both American optometrist and Philadelphia-based chemical company Rohm and Haas came out with scleral lenses which incorporated plastic elements into the typical glass lens. By 1938, all-plastic contacts were being constructed from a new material known as polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA). PMMA was much easier to form into the proper shape than glass, was incredibly thin and much safer to wear.

One decade after plastics were incorporated into contact lenses, a design improvement harkening back to the earliest days of contact lens technology was developed by American optical technician Kevin Tuohy. In 1948, Tuohy worked with a plastic scleral lens which had lost enough of its peripheral plastic layer that it only covered the cornea, closely approximating aspects of the Descartes design from centuries earlier. This provided the required amount of vision correction without covering any area of the sclera.

Over the years, shortcomings with the PMMA plastic material began to be made apparent. Like glass, PMMA is impermeable to air, making it difficult to deliver the proper amount of oxygen to a wearer’s eyes and creating a great deal of discomfort over time. The next generation of contact lenses would be constructed from a material known as hydroxyethylmethacrylate (HEMA), the first type of hydrophilic plastic known as a “hydrogel” created for use with contact lenses.

The plastic material HEMA was discovered in 1958 by Czechoslovakian chemist Otto Wichterle. When he realized that HEMA was a plastic that was capable of retaining moisture, he conceived of a use for HEMA in the fabrication of contact lenses. Hydrogels can absorb as much as 85 percent to 90 percent of its weight in water, becoming softer and more flexible as they do so. The widespread incorporation of HEMA into contact lenses required the development of a completely new manufacturing process, known as “spin casting.” Wichterle innovated the first spin casting process with the use of a phonograph motor and parts from a child Erector set for molding the plastic into the proper shape. His technology was licensed in the early 1970s by Bausch & Lomb, which brought hydrogel lenses to the American market for the very first time.

As we’ve pointed out, innovation in contact lens technologies continue to come to fruition according to the patent filings at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Along with daily disposable lenses, American consumers can also choose from extended wear varieties, some of which can be worn up to 30 days without causing irritation. Many choose to wear soft lenses made from hydrogels but rigid gas permeables, which are less flexible than hydrogels but are more durable and result in a crisper view. As contact lenses continue to incorporate more sophisticated electronic technologies, we’ll likely see many more applications of contacts beyond its current applications as primarily a solution for optical issues in optometry patients.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

No comments yet.