Starting in November 2000, the USPTO started publishing patent applications 18 months after their earliest filing date. So the simple assumption is that you file a patent and 18 months later it get publicized, right? Well, things aren’t that straightforward.

Starting in November 2000, the USPTO started publishing patent applications 18 months after their earliest filing date. So the simple assumption is that you file a patent and 18 months later it get publicized, right? Well, things aren’t that straightforward.

First of all, the “earliest filing date” really means the priority date since the US moved to a first-to-file system, so it’s really 18 months after the earliest priority date (including foreign filings). Also, the patent application can be filed up to 12 months after the invention is first sold into the market or otherwise disclosed (which becomes the priority date), so an application that take advantage of the 12-month grace period could be published as early as 6 months after filing.

There are also lots of exceptions to the 18-month rule: A filer can request early publication (because in some cases you can now claim pre-issue royalties if the patent is granted); the filer can elect to not file for foreign patents and request non-publication at the time of filing to prevent the filing from being published in the US; provisional applications are not published and remain secret; continuation-in-part and divisional applications based on years-old patent applications can be published within a few weeks of filing; the patent filer can request non-publication or the government can prevent publication due to national security reasons; etc.

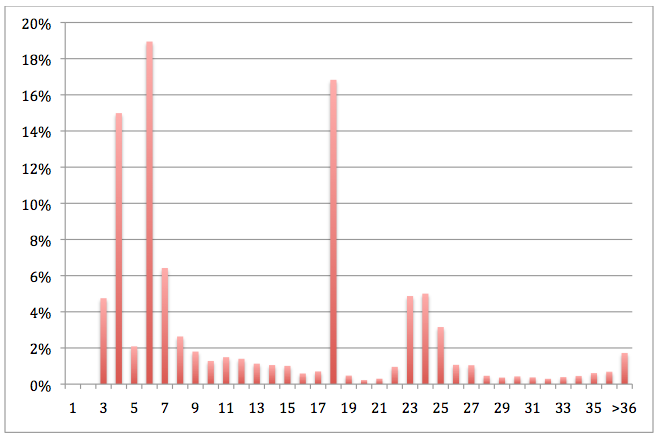

In practice, the graph below shows that over half of US patent applications are published within a year after they were filed. The analysis below is based on the patents published in June 2015, based on how many months passed between when they were filed and when they were published:

There are several “spikes” in the data:

- The patents published at 3-month and 4-month are mainly divisionals and continuation-in-part and early-publish requests that are published as soon as they’re fully processed by the USPTO system.

- The most frequent publishing delay is 6 months – these are patents that were filed 12 months after the priority date.

- The 18-month spike is the case where the priority date is the same as the filing date for a new application, and the vanilla 18-month rule applies.

- The increase at 23 and 24 months is due to applications that are first filed as international applications (either in a foreign country or via a PCT application with WIPO) to preserve the international priority date, then later are filed with the US. The USPTO filing date is set to the earlier WIPO filing date rather than the later US filing date (the “371 Date”) of the US application.

So the simple 18-month concept turns out to be pretty complex and usually incorrect, since on average patent applications are published well before the 18-month delay.

Based on the analysis of the patents published in June 2015, fully 55% of patent applications are published within 12 months of filing. This actually makes patents more similar than you’d expect to journal articles, which typically take 3-9 months after submission to be published.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

8 comments so far.

Arleen zank

August 5, 2015 05:36 amThe article also doesn’t account for a variety of move to the top of the docket accelerated examination programs.

American Cowboy

August 4, 2015 03:22 pmAnon is right. The public is guaranteed the quid of publication, while the patent applicant maybe can get the Quo of issuance…. until of course the scotus gets hold of the patent and squishes it to smithereens.

Anon

August 4, 2015 09:00 amI think that there are several more pernicious ramifications of the publication change to patent law than the mere phantom (or not) timing aspect.

Items much more aligned with the fundamental Quid Pro Quo exchange.

Benny

August 4, 2015 05:34 am” 55% of patent applications are published within 12 months of filing. This actually makes patents more similar than you’d expect to journal articles”

I dispute the logic of that statement. Since most of the early publication applications are continuations and divisionals, their specification will usually be identical (in substance) to the original application – which in most cases would have been published 18 months after filing. Therefore, they are merely a repeat publication and not first publication.

Ron Katznelson

August 4, 2015 05:23 amThanks for the informative graph, though a couple of clarifications and corrections are in order here. It is unclear whether the graph is for the publication date of patents or patent applications. The article focuses on publication of applications but the article states: “The analysis below is based on the patents published in June 2015,…” and ”The patents published at 3-month and 4-month…. The following corrections should also be noted:

(1) The following statement in the article is clearly wrong: “the patent application can be filed up to 12 months after the invention is first sold into the market or otherwise disclosed (which becomes the priority date), so an application that take advantage of the 12-month grace period could be published as early as 6 months after filing.” First, the applications shown published at the 6 months spike are all post-AIA applications (having published in June 2015), for which there is no ‘public use’ or ‘on sale’ grace period. Those who assume there is such post-AIA grace period do so at their peril. Second, the publication statute in Section 122 contains nothing that starts a publication clock at any ‘public use’ or ‘on sale’ event – think about it: does anybody provide the PTO with information on their ‘on-sale’ date? Rather, the spike at 6 months is simply the publication of applications claiming priority to foreign-filed applications which were filed in the US under the Paris Convention at the end of the “Paris year” and are published 18 months after their foreign filing date.

(2) The article omits an important reference to continuations. But the publications at 3-month and 4-month are mainly continuations — with a lot less “divisionals and continuation-in-part” that the article speaks of. Those studying PTO statistics would find that there are about twice as many continuations filed compared to divisionals and four times as many compared to continuations in part.

Mike

August 3, 2015 05:29 pmCould you please clarify…

“Also, the patent application can be filed up to 12 months after the invention is first sold into the market or otherwise disclosed (which becomes the priority date)…”

I don’t understand how the sale or disclosure (outside of a patent application) of an invention can establish a priority date with respect to publication of a subsequently filed application.

Thanks

American Cowboy

August 3, 2015 12:04 pmI repeat a request from before: Has a patentee ever gotten the post-publication, pre-grant reasonable royalties that publication is suppose to provide? I have never seen a case where they have, but maybe I missed one.

Or a case where the infringer voluntarily paid those royalties? (heh-heh!)

Luis Figarella

August 3, 2015 07:39 amExcellent article John. One note, Provisionals are not published, but they become ‘visible’ and readable in Public PAIR once the patent publishes. And of course, once an application publishes, ALL transactions (including Office Actions, etc.) are visible in Public PAIR, by anyone.