Like the dog days of summer stimulating an algae bloom in a stagnant pond, there seems to be a burst of articles asserting that the patent system is harmful to innovation. The tendency is to ignore such attacks, but as we’ve learned to our sorrow unless rebutted theories that patents exploit the public interest can take root in a society where fewer and fewer people know how the products that we all depend upon are created.

Like the dog days of summer stimulating an algae bloom in a stagnant pond, there seems to be a burst of articles asserting that the patent system is harmful to innovation. The tendency is to ignore such attacks, but as we’ve learned to our sorrow unless rebutted theories that patents exploit the public interest can take root in a society where fewer and fewer people know how the products that we all depend upon are created.

Soon after Gene Quinn rebutted a recent article in The Economist attacking the patent system a friend sent me The Case Against Patents by Professors Michele Boldrin and David K. Levine, upon which The Economist based much of its argument. The authors are “Distinguished University Professors of Economics” at Washington University and “Research Fellows” with the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Here’s the gist of the paper:

The case against patents can be summarized briefly: there is no empirical evidence that they serve to increase innovation and productivity, unless productivity is identified with the number of patents awarded—which, as evidence shows, has no correlation with measured productivity. This disconnect is at the root of what is called the “patent puzzle”: in spite of the enormous increase in the number of patents and in the strength of their legal protection, the US economy has seen neither a dramatic acceleration in the rate of technological progress nor a major increase in the levels of research and development expenditure.

Both theory and evidence suggest that while patents can have a partial equilibrium effect of improving incentives to invent, the general equilibrium effect on innovation can be negative. The historical and international evidence suggests that while weak patent systems may mildly increase innovation with limited side effects, strong patent systems retard innovation with many negative side effects.

There follows pages of citations from studies “proving” that patents are harmful until we come to the punch line. While Boldrin and Levine believe we should abolish the patent system, they would settle for another approach:

We do believe, along with many of our colleagues, that a patent system designed by impartial and disinterested economists and administered by wise and incorruptible civil servants (emphasis added) could serve to encourage innovation. In such a system, very few patents would ever be awarded: only those for which convincing evidence existed that the fixed costs of innovation were truly very high, the costs of imitation were truly low, and demand for the product was really highly inelastic.

Perhaps Boldrin and Levine have themselves in mind as the kind of “impartial and disinterested economists” needed to run this imperious patent system.

[Joe-Allen]

Not content with “fixing” the patent system, the professors also call for reforming the pharmaceutical industry. One idea is having the National Institutes of Health fund Phase II and III clinical trials as “public goods,” deciding through bidding which companies are allowed to perform them. The winners would be required to sell resulting drugs at “economic cost” since the government is now running the show. They gloss over who would bother to make new drug discoveries knowing that the government would take them away. But not to worry, with “impartial, disinterested, wise and incorruptible” bureaucrats rather than companies in charge of drug development, what could possibly go wrong?

An indication of how innovators would fare in the professor’s system is shown by their dismissal of the Wright brothers as having “made a modest improvement in existing flight technology that they kept secret until they could lock it down on patents, then used their patents both to monopolize the US market and to prevent further innovation for nearly 20 years.” Somehow that description seems to miss something. While it’s true the Wright brothers spent years in patent litigation, shouldn’t we note they were the first humans in history to successfully fly and control—others had flown and crashed– a heavier than air machine?

The story of the development of the airplane underscores a serious flaw in the professor’s theory:

In the period preceding the December 17, 1903 Wright brothers’ triumph at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, the U.S. government spent $70,000 on a grant to Dr. Samuel Langley to develop a heavier-than-air flying machine. The award of this grant followed standard bureaucratic procedures. Dr. Langley, director of the Smithsonian Institution, was one of the most renowned scientists of the time. When Dr. Langley became interested in investigating flight he was able to marshal tremendous technical and financial resources.

The selection of Langley as the recipient of government funding was technically unassailable. It was the type of decision that a well motivated government bureaucracy would make time and again. The credentials were impressive. The funding was more than adequate. Yet, despite the head start and more lavish budget enjoyed by Dr. Langley, it was the Wrights who succeeded.

On October 7, 1903, the aircraft developed by Dr. Langley’s team was deemed ready for a test flight. The aircraft was to be launched from a catapult on a houseboat in the Potomac River, with Charles Manly serving as pilot. Excitement filled the air as the houseboat reached the launch site. A large crowd gathered, fireworks were set off, and newspapermen jockeyed for position in the hope of witnessing the momentous occasion of man’s first flight.

Hopes were raised and hearts quickened as the aircraft’s engine roared to life. At full throttle the craft was released from restraint and lunged along the catapult track toward launch. A few seconds of glorious acceleration were followed by an unceremonious plunge into the Potomac by the would-be airplane. The pilot and aircraft were salvaged and preparations were made for another flight. On December 8, 1903, with diminished fanfare, another test flight was attempted. Unfortunately the aircraft became entangled in the launching mechanism, was severely damaged, and toppled into the river.

Little more than a week later the Wright brothers successfully flew a heavier-than-air machine. Disappointed at being bested in the effort to develop an airplane, Dr. Langley, in a fashion that has come to characterize the persistent failure of government undertakings, laid much of the blame on “inadequate” Federal funding.

It’s not hard to guess what would happen if the government took over drug development.

You might imagine after turning the patent and drug development systems on their heads that the professors would have exhausted their arsenal of theories, but they also provide guidance for managing government funded research. They recommend a return to the pre Bayh-Dole policy “according to which the results of federally subsidized research cannot lead to patents, but should be available to all market participants. This reform would be particularly useful for encouraging the dissemination of innovation and heightening competition in the pharmaceutical industry.” (emphasis added)

Actually, such nonsense underscores why relying on those with only theoretical expertise for policy advice is so dangerous. It was the utter failure of these practices that led to the enactment of Bayh-Dole. Before the law injected the incentives of patent ownership into government funded R&D, Congress found that not a single drug had been commercialized when the government took away academic inventions, offering them for development under non-exclusive licenses. No company was willing to invest the considerable time and money needed to take a new drug to market without adequate patent protection. And this phenomena wasn’t limited to pharmaceuticals. Less than 5% of the 28,000 patents that government had amassed in its portfolio before Bayh-Dole were ever licensed under the policies the professors would have us restore.

Since Bayh-Dole allowed universities and small companies to own and manage inventions they make under federally-funded R&D more than 153 new drugs and vaccines are now on the market. See The Role of Public-Sector Research in the Discovery of Drugs and Vaccines. Before Bayh-Dole companies were reluctant to have their best and brightest work with their academic counterparts because resulting inventions would be taken by the government. Now industry-academic R&D partnerships are a driving force in our economy. A recent study calculates the contribution of academic patent licensing at $1.18 Trillion to our economy while supporting almost 4 million U.S. jobs.

The Economist Technology Quarterly best summarized what the Bayh-Dole Act accomplished:

Remember the technological malaise that befell America in the late 1970s? Japan was busy snuffing out Pittsburgh’s steel mills, driving Detroit off the road, and beginning its assault on Silicon Valley. Only a decade later, things were very different. Japanese industry was in retreat. An exhausted Soviet empire threw in the towel. Europe sat up and started investing heavily in America. Why the sudden reversal of fortunes? Across America, there had been a flowering of innovation unlike anything seen before.

Possibly the most inspired piece of legislation to be enacted in America over the past half-century was the Bayh-Dole act of 1980… (that) unlocked all the inventions and discoveries that had been made in laboratories throughout the United States with the help of taxpayers’ money. More than anything, this single policy measure helped to reverse America’s precipitous slide into industrial irrelevance. (emphasis added)

There’s a good reason why the Bayh-Dole Act still works like a finely honed machine after 35 years. When crafting it we didn’t go to theorists. Instead, we sought those with actual commercialization experience. With their input, the law relies on the incentives of patent ownership to drive the system. The role of the federal agencies is to fund the research, enforce some simple rules, and get out of the way. Bayh-Dole’s become an internationally recognized best practice for a simple reason: it works.

So what about the value of patents to small companies? The article Don’t believe those who tell you American innovation is losing its way makes an interesting observation:

Josh Wolfe, founding partner of Lux Capital (a venture capital firm), reckons the overall pace of innovation in America hasn’t changed—just that where it happens is shifting. The new model is that small, private firms do the innovation and, if successful, are bought by big public firms…

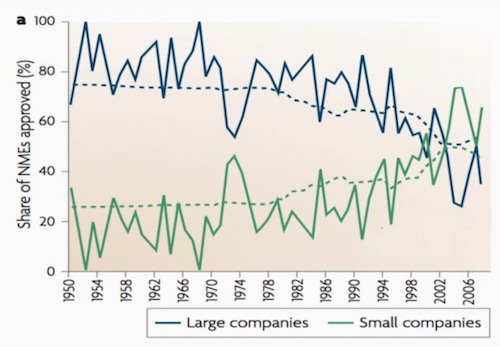

That has already happened in pharmaceuticals. Big pharma firms do less and less R&D in-house, relying instead on small biotech startups to come up with new potential drugs, and then buying them or licensing their technology. That’s visible in this chart from Jeff Kindler, also of Lux, which shows the growing share of new drugs that originated with small companies:

You can bet the farm that small companies looking to be acquired or expand in the life sciences market protect their discoveries through patenting.

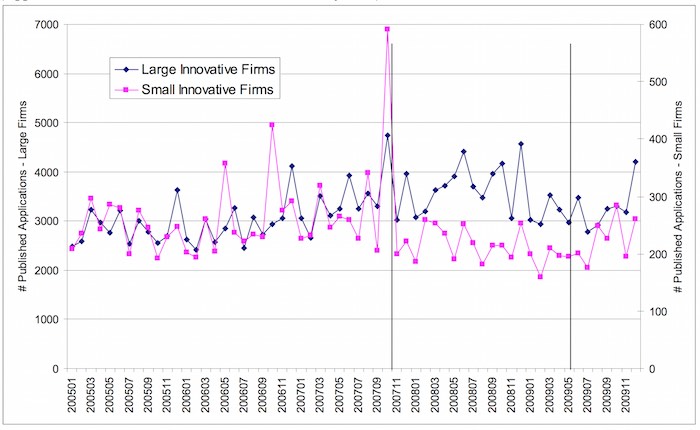

A report by to the U.S. Small Business Administration concludes: “Our earlier reports found that small firms participate extensively in the patent system, they produce large numbers of patents relative to their size, and these patents tend to have very strong quality metrics.”

The report flags the reduction in small business patent filings during the ’07- ’09 recession as a cause for national concern: “Since small firms have been shown to develop high impact technologies, and a higher percentage of green and leading edge technologies, this result has significant policy implications.” This certainly implies that patenting by small entrepreneurial companies is critical to U.S. competitiveness.

Thus, the patent system is not a tool for entrenched interests to stifle competition as Professors Boldrin and Levine would have us believe. Patents allow independent inventors and small companies to compete against better funded rivals, who would otherwise simply take away their inventions.

The next time your flight lands safely, you might say a silent thank you to the Wright brothers. They never graduated from high school, yet showed the world how to travel up into the air and come back down again. Our system allowed two mechanics from Dayton, Ohio– who paid for their research out of sales from their bicycle shop– to beat an elite, government funded competitor. Modern equivalents of the Wright brothers still bet everything they own on their patented inventions, despite knowing the odds are stacked against them. The patent system may look a lot more valuable to these entrepreneurs fighting for survival in the marketplace than it does to someone gazing down from the Ivory Tower.

And perhaps one reason our nation is in such distress is that so many policies are based on recommendations from those without any practical experience. Anyway, that’s my theory.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

26 comments so far.

Night Writer

August 26, 2015 10:34 amThis, by the way, is one reason I would very much like Lemley to disclose how he is keeping his start-up IP locked down.

The one thing that real economist in academia agree is that draconian employment agreements are serious, serious impediments to innovation.

Night Writer

August 26, 2015 10:32 amAnon, actually I miswrote that. I meant to say that I think some of the academics aren’t aware of this. I agree with you that the big corporations are very aware of this. And, by the way, they have been caught agreeing not to compete for each other’s employees, which is exactly the sort of thing that draconian employment agreements would take care of—lock those employees down so you don’t have to pay them as much.

Anon

August 26, 2015 07:16 amNight Writer,

To the contrary, I believe that they very much have an idea, and are perfectly “OK” with less real innovation, as long as they are the ones whom have already climbed up the ladder. Do not mistake wanting to wreck a system that threatens them with ignorance about that system. When money is involved, the reverse of the adage concerning ignorance and malice takes hold.

Night Writer

August 26, 2015 05:31 am>>trade secret

This is one area that is critical to dispersing the anti-patent movement. The anti-patent movement (lead by Google) is also pushing hard for stronger trade secret support and, in particular, they want legislation that would give them causes of action in CA for employees who leave the company and practice the trade secret or disclose the trade secret. In effect, what they want to be able to do is lock down their employees.

And, —-if there is anything that is agreed upon by economist—it is that people being able to leave the companies is a requirement for innovation.

That is why I would like Lemley to tell us how he locks down his IP for his start-up. The anti-patent movement actually wants a very dark world where everything becomes a secret and employees cannot move to new jobs, or they are so ignorant of the real world they have no idea of the consequences of the policies they are advocating.

Eric Berend

August 25, 2015 12:25 pmAs an individual inventor with important new technology in the balance, this malarkey will all take much too long to resolve, even if legislators are somehow persuaded to see the recent errors of their ways.

Increasingly, the only (severely compromised) options appear to be: trade secret, with all of the risks that entails; or, emigration, to a sovereign regime that still offers substantial legal patent protections for the individual inventor.

Night Writer

August 25, 2015 10:59 amAnother example of not responding to criticism: Lemley. He has a start-up. How is he protecting his IP? My guess is that he is using draconian employment contracts. But, he won’t disclose.

Night Writer

August 25, 2015 10:23 amjohn howells : one problem is that we who actually do patent law just don’t have time for this. I can tell you that actual patent law with real technology companies is nothing like the anti-patent crowd claims. I see engineers with Ph.D.’s struggle all the time to come up with stuff that is patent worthy. Patents are integrated into the corporations. They help explain what they are doing to everyone at the corporations, they motivate the engineers to come up with inventions that are good enough for a patent application, they motive v.p.’s to build research centers for more patents, etc….. that is the real world.

The Google fueled K street and academics have created a fantasy world that has nothing to do with my real practice.

John Fraser

August 25, 2015 10:01 amJoe. Thnaks again for marshaling the facts and opinions. I really enjoyed the quote for the book about the Wright Brothers – the whole book is a case of American tinkerers and the inventive genius that made heavier than air flight possible. Like others who posted previously, I am appalled that such experts without practical experience critique the Patent system and then say they have the expertise and experience to ‘do it right”. What garbage !

EG

August 25, 2015 09:24 amHey Joe,

Thanks for your piece exposing these “economic charlatans” masquerading as academics. I almost went ballistic as I read your piece. Are Boldrin & Levine for real? The should be castigated and condemned for spouting such malarkey.

A. Nony Mus

August 25, 2015 08:47 am… and administered by wise and incorruptible civil servants…

We already have that. They’re called: “patent examiners.”

Might I respectfully disagree with that remark, especially when it comes to some of the examiners of the USPTO. Some are indeed good and diligent and, yes, wise, but others are stupid, incompetent, and in many cases downright dishonest. You KNOW they couldn’t possibly have reached the conclusion they do, had they honestly considered the facts and the art, but they do. You shake your head in bewilderment and wonder what on earth they were drinking and/or smoking on that particular day (and wondering how you could get some). I would rate the USPTO as the worst of the major examining offices, and not really that far ahead of some Asian countries, which shall remain nameless.

With regard to the Boldrin book, I’ve read it, and while I don’t agree with its basic conclusions, it does make serious arguments, which merit serious consideration, not being howled down in what appears to be the typical IP Watchdog manner. The patent system needs fixing, and perhaps that fixing might involve throwing it out and starting again. It ain’t gonna happen of course, so we soldier on. Half a loaf is better than none at all.

A. Nony Mus

August 25, 2015 08:47 am… and administered by wise and incorruptible civil servants…

We already have that. They’re called: “patent examiners.”

Might I respectfully disagree with that remark, especially when it comes to some of the examiners of the USPTO. Some are indeed good and diligent and, yes, wise, but others are stupid, incompetent, and in many cases downright dishonest. You KNOW they couldn’t possibly have reached the conclusion they do, had they honestly considered the facts and the art, but they do. You shake your head in bewilderment and wonder what on earth they were drinking and/or smoking on that particular day (and wondering how you could get some). I would rate the USPTO as the worst of the major examining offices, and not really that far ahead of some Asian countries, which shall remain nameless.

With regard to the Boldrin book, I’ve read it, and while I don’t agree with its basic conclusions, it does make serious arguments, which merit serious consideration, not being howled down in what appears to be the typical IP Watchdog manner. The patent system needs fixing, and perhaps that fixing might involve throwing it out and starting again. It ain’t gonna happen of course, so we soldier on. Half a loaf is better than none at all.

john howells

August 25, 2015 08:04 amOn the topic of whether Boldrin and Levine respond to fact-based correction of their factual mistakes (they do not), see the series of articles by George Selgin and John Turner that rebut Boldrin and Levine’s assertion that Watt’s patent on the separate condenser retarded steam engine development: this is a case where the ‘correctors’ persisted in pointing out the facts over a period of years precisely because Boldrin and Levine persisted if telling their preferred counter-factual story. It culminated in an excellent article in J Law and Economics. This work was done by ‘economists’. I may be a mere ivory tower academic myself but if practitioners would note such work and cite to it and keep it in public view as a sobering contrast to the work of such as Boldrin and Levine, rather than dismiss academics and universities in their entirety for not having ‘experience’ you might serve your own cause and the cause of precise and factual scholarship in the universities even better.

Selgin, G., J.L. Turner. 2006. James Watt as Intellectual monopolist: Comment on Boldrin and Levine. International Economic Review. 47 (4) 1341 – 1348.

Selgin, G., J.L. Turner. 2009. Watt again? Boldrin and Levine Still Exaggerate the Adverse Effect of Patents on the Progress of Steam Power. Review of Law and Economics. 5 (3) 1101-1113.

Selgin, G., J.L. Turner. 2011. Strong Steam, Weak Patents, or, the Myth of Watt’s Innovation-Blocking Monopoly, Exploded.

Night Writer

August 25, 2015 08:02 amBy the way, thanks David for your posts. It is great to see that there are still some people that care about reality.

Mark Summerfield

August 25, 2015 07:11 amEconomics is a pseudo-science. By this, I do not mean to imply that it is of no value, our that all economists are charlatans. I mean it in the very literal sense that, although much economic study aspires to be viewed as a legitimate science, it suffers from the failing that its methods and results are not subject to objective falsification.

Thus, some economists can tell us, for example, that the patent system is a brake on innovation, and that such endeavors as the development of new drugs would be more effectively managed and funded through bureaucratic decision-making. Others will advocate for a market-based solution, which of course requires a mechanism to create a market for innovation… a.k.a. the patent system.

A true science is tested by the extent to which realty accords with theory. And while both of the above approaches work in theory, only one of them has proven effective in practice. The other should have been discredited once and for all with the fall of the Berlin wall. But apparently not.

Benny

August 25, 2015 07:04 amDavid Stein,

I disagree with you assertion that patent examiners are “wise and incorruptible”. Incorruptible, yes, so I would assume, but wise? Not all of them, not by a long shot. “Inconsistent” is nearer the mark. If they are so wise, why are patent attorneys constantly arguing and disagreeing with them in responses to office actions?

Curious

August 24, 2015 07:26 pmI took the opportunity to track down “Boldrin & Levine: Against Intellectual Monopoly,” which is published on Michele Boldrin’s website. I have to say that most examiners have a better grasp of logic than these guys — and that is saying a lot. I have never seen so many poorly defined anecdotes used as evidence in my life. I could spend a month shredding their analysis to pieces. However, I have neither the time nor the inclination to do so. Unfortunately, it is tripe like this that gets cited by those farther up the ivory tower food chain.

Night Writer

August 24, 2015 05:49 pmPaul Cole says: >>Those who equate economists with charlatans

No idea why you floated that up there as if it has anything to do with this thread. Certainly criticizing two economist is not “equat[ing] economists with charlatans.” You seem to throw in comments that appear to be meant to diminish any thread that is not anti-patent. You are more subtle than MM, but your intent appears to be the same.

Night Writer

August 24, 2015 05:18 pmIt would be interesting if the wonder twins have ever studied the old USSR system. It sounds like they want to re-create it. It did not perform well.

What you have to love about all these “experts” is the way they use hindsight and assume that some wise person can sit up on a hill and pick out the inventions worthy of a patent. That method has been shown to not work. The only method shown to work is applying 102 and 103 with real prior art.

I couldn’t write the nonsense they write and sleep at night. I guess being fueled with massive grants to burn the patent system down buys a lot of academics.

David Stein

August 24, 2015 05:16 pmOh, I don’t believe that economists are charlatans by any means. Economics is an important topic, and it explains a great deal about how many human systems operate – and not just financial systems: Freakonomics is an excellent example.

But economists are a very specific breed of intellectual. Their traits are much better suited for academic analysis than actual leadership of institutions – they’ve not exactly done a great job at the Federal Reserve. And why would anyone presume that they know anything about the promise of technology?

Paul Cole

August 24, 2015 04:42 pmThose who equate economists with charlatans may care to examine the rear face of a £20 note when they visit England. On it they will find a quote attributed to Adam Smith: “The division of labour in pin manufacturing: and the great increase in the quantity of labour that results.” My e-mail enquiries have not revealed whether these exact words were ever written by Adam Smith or are the creation of some flunkey in the Bank of England. But apparently Adam Smith had never visited a pin manufactory.

I used to regard The Economist as an interesting and authoritative magazine.

Night Writer

August 24, 2015 03:30 pmOne thing left off this piece is the motivation of the Wright brothers. Would they or any inventor go to such extraordinary measures to invent if you they knew that the government or a big corporation would just take what they did? And, likely, without patents the big corporation or government would lie and said they invented it.

Moreover, I wonder if the wonder twins get that the system they are studying has been shaped by patents. Maybe they should take their disconnected thoughts and do a comparison with a country that has a high innovation rate and no patents–oh wait, such a country doesn’t exist. I wonder why.

And, why is that people like Michele Boldrin and David K. Levine never respond to criticism? I’ve noticed that Lemley has never responded to criticism of his “theories”. I don’t think you can call yourself an academic without being willing to respond to criticism of your “theories.”

Night Writer

August 24, 2015 03:16 pm“This is one of the best pieces I’ve seen at IP Watchdog.”

I agree too. I think the two “economist” should move to the USSR in a time machine during the 1970’s.

I wonder what makes people like Boldrin and Levine (and Lemley). The only thing I can figure out is that they write a load of BS and are richly rewarded for it by universities. This then creates an impression in their minds that they know what they are talking about. Bizarre. I think it is called disconnected cognition. It is a form of mental illness when not fueled by mega-university bucks coming on the backs of children going into debt.

David Stein

August 24, 2015 02:49 pmI’m reading this article – Allen is right: it’s chock-ful of material that’s just flatly wrong and uninformed.

For instance, the refutation of the value of published research goes like this:

First: The value of the specification is different than the disclosure value of the public disclosure that the patent enables. Engineer #1 is unlikely to learn about Engineer #2’s development by reading Engineer #2’s patent application – but is likely to learn about it in an academic publication / trade journal / conference presentation / web publication, which Engineer #2 can freely release because the invention is protected by the patent. The alternative of having no patents is that technology widely becomes proprietary, protected both by trade secret and by clumsy, frustrating mechanisms like DRM.

Second: Right, go ask Google if its engineers were assisted at all by Apple’s work. Then as Apple if Google’s engineers were assisted by Apple’s work. Think you might get different answers? Could it be that the parties have vested interests that at least bias their perceptions and memory, and at most prevent them from telling the truth about things?

I don’t recall Samsung stepping up and saying, “yeah, the Galaxy is our version of the iPhone, which we scrutinized and copied in detail.” As I recall, that admission only came out in discovery.

Bonus: These academics mention the Bayh-Dole Act exactly once – and in this context: “We advocate returning to the rule prior to the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980.” There is no discussion or even recognition of why the Bayh-Dole Act came into existence in the first place.

So often, these ivory-tower reform advocates are completely out of touch with how the system actually operates, and they make these outlandish statements that are dumbfoundingly uninformed. The problem is that they only talk to each other, not to people in the field who can fill in the gaps.

Paul Morinville

August 24, 2015 01:02 pm“This is one of the best pieces I’ve seen at IP Watchdog.”

Agreed.

Paul Morinville

August 24, 2015 01:01 pm“perhaps one reason our nation is in such distress is that so many policies are based on recommendations from those without any practical experience”

Perhaps.

Or perhaps they do have practical experience but that practical experience is directed to keeping large multinationals insulated from competition and forever able to enrich those making the recommendations.

That is my take on patent reform. After all, most of the recommendations come from Google, Facebook, Amazon, etc. Hardly companies without practical experience.

David Stein

August 24, 2015 12:54 pmThis is one of the best pieces I’ve seen at IP Watchdog.

Some of these quotes from the textbook are delicious:

Economists are generally known to have two qualities:

1) Risk aversion, in the sense of overprioritizing safety, overestimating hazards, and undervaluing potential benefits (hence the moniker: “the dismal science,” and phrases like: “knowing the cost of everything, and the value of nothing”).

2) Tremendously poor skills of prediction, because their attachment to tidy, theoretical models often fails to match reality (most recently apparent in Alan Greenspan’s shocking discovery of a “flaw” in human nature, where unfettered investors choose short-term gains over long-term viability).

Yes, by all means, let’s take these people and put them in charge of a system of allocating property rights to speculative investment over promising technology.

We’ll end up with a patent system where nothing is ever patent-eligible until its viability and value are proven beyond doubt by fifty years of research. Today’s economist-driven patent office might finally be issuing a patent for the Sony Walkman.

We already have that. They’re called: “patent examiners.”

Are these esteemed authors aware that we already tried that once, in the 1930’s? And that it was such an unmitigated disaster for the marketplace that Congress ended up completely rewriting patent law in 1952 to get away from the courts’ nonsense?