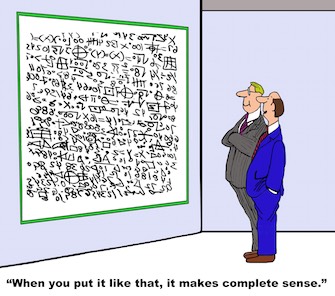

Determining what is obvious and, therefore, not patentable, is a difficult matter. Indeed, one of the most frustrating things I do as a patent attorney is advise inventors on whether their invention is obvious. It is frustrating not because of any failing or lack of knowledge on the part of the inventor, but it is frustrating because the legal determination about whether an invention is obvious seems completely subjective and sometimes even arbitrary.

Determining what is obvious and, therefore, not patentable, is a difficult matter. Indeed, one of the most frustrating things I do as a patent attorney is advise inventors on whether their invention is obvious. It is frustrating not because of any failing or lack of knowledge on the part of the inventor, but it is frustrating because the legal determination about whether an invention is obvious seems completely subjective and sometimes even arbitrary.

The big problem I have with obviousness is that it is so unevenly applied. In some technology areas nothing ever seems to be obvious, in other areas virtually everything seems to be obvious. This requires a patent attorney or patent agent to have familiarity with how patent examiners interpret the law of obviousness in a particular innovative area. You might suspect that this would mean that for low-tech gadgets it is more difficult to describe an invention that is non-obvious; while in high tech areas it would be easier to describe an invention as non-obvious. That frequently isn’t the case though, which leads to even greater frustration for inventors.

If Irving Inventor could get a patent on that simple kitchen gadget how is it possible that my complex software program that has never existed before could be considered obvious? That is a good question, and one without a satisfactory answer in my opinion. There is little that seems fair when you compare the way obviousness is interpreted by different Art Units at the Patent Office, which suggest that obviousness has much to do with the way Supervisory Patent Examiners (SPEs) view the inquiry. Different SPEs have different philosophical views of the patent system, which is one reason why you get such disparate treatment of applicants. Regardless of the reasons, what seems clear is that the law of obviousness is often bizarre and has more to do with the personal perceptions of the decision maker than any enlightened or guiding principle.

The issue of obviousness is where the rubber meets the road when it comes to patentability. It has always been difficult to explain the law of obviousness to inventors, business executives and law students alike. Since the United States Supreme Court issued its decision in KSR v. Teleflex in 2007 it has become even more difficult to provide a simple, coherent articulation of the law of obviousness that is at all intellectually satisfying. That is in no small part due to the fact that the determination about whether an invention is obvious is now completely subjective.

If you look at the Federal Circuit cases it seems that there is an awful lot of reasoning (if you can call it that) that justifies a conclusion already formed. The state of obviousness law allows a decision maker to make a determination about obviousness that seems appropriate from a subjective standpoint, and then weave the “reasoning” backwards to justify the conclusion already reached. The way that this used to be prevented was with what was called the teaching, suggestion or motivation (TSM) test. If there was no teaching, suggestion or motivation to combine references the invention could not be obvious, period. The Supreme Court thought that test, which was a great barrier against hindsight working into the calculus, was too permissive and lead to patents that on their face should clearly never have issued.

The question inventors want to know is whether they will likely be able to obtain a patent, which is a perfectly reasonable question. There is no point wasting good money chasing a patent that likely will never issue. Application of the law of obviousness seems to suggest that when in doubt an invention will be considered obvious. Therefore, it becomes essential to identify all of the possible differences between the invention and the prior art, both from a functional and structural standpoint, but now I’m getting ahead of myself. This article is but a first step in the journey to greater understanding of the law of obviousness.

Before we can understand the peculiar nuances that have turned obviousness determinations into a purely subjective inquiry we need to step back and start at the beginning.

Novelty vs. Obviousness

In assessing whether an invention is patentable there are primarily two questions that must be answered. First, is the invention new (i.e., novel) compared with the prior art? Second, is the invention non-obvious in light of the prior art? We engage in this two-fold inquiry to determine what, if anything, can reasonably be expected to be obtained in terms of patent claim scope.

The question about whether or not there is any single reference that is exactly identical to the invention being evaluated is merely a threshold inquiry. If a prior art reference is found that discloses all the elements of the invention, the inquiry ends because no patent can be obtained. If no single prior art reference identically describes each and every aspect of the invention this novelty hurdle has been cleared. As you can probably imagine, it is not at all uncommon for an invention to clear the novelty hurdle, or at least be capable of clearing the novelty hurdle because with the addition of enough characteristics and limitations eventually the invention will not be identical to the prior art.

Even if the invention is not identical to the prior art it is possible to be denied a patent because the invention is obvious. This is where many inventors become mystified, and some even extremely upset. When I do a patent search and offer an opinion the only time I ever get complaints is when I tell an inventor that I don’t think their invention is patentable, or that it may be patentable but the resulting claims will be quite narrow, perhaps so narrow that the patent claims will not be commercially viable. This opinion is almost always reached due to obviousness concerns. It is very difficult for an inventor to have something that is not identical to the prior art and yet still be told that their invention is likely not patentable because it will be determined to be obvious.

When approaching an obviousness determination it is essential to understand what makes the invention unique. It is also necessary to start to envision the arguments that can be made to distinguish the invention over the totality of the prior art. This is required because when a patent examiner deals with issues of obviousness they will look at a variety of references and pull one element from one reference and another element of the invention from another reference. Ultimately the patent examiner will see if they can find all the pieces, parts and functionality of the invention in the prior art as a whole, and conclude that a combination of the prior art references discloses your invention. This is a bit of an oversimplification because on some level all inventions are made up of known pieces, parts and functionality. The true inquiry is to determine whether the combination of the pieces, parts and functionality found within the applicable technology field of the invention would be considered to be within the “common sense” of one of skill in the art such that the invention is merely a trivial rearrangement of what is already known to exist.

What is and is not “common sense” makes an objective inquiry extremely difficult to say the least. The Patent Office has attempted to interpret KSR in a way that focuses on predictability of results and expectations of success. With the test focusing on “common sense” an awful lot is left to the decision maker in the subjective realm.

One highly effective way to combat an obviousness rejection is to point out that not all of the pieces, parts and functionality that make up an invention can be found within the relevant prior art. But even this is not a guarantee that a patent examiner or reviewing Judge must find that the invention is non-obvious. Nevertheless, it is still a good place to start.

The way I approach obviousness is to identify the closest references and work to articulate what is unique in an invention, searching for a core uniqueness that exists so that a unique invention can be articulated (if possible). We focus on anything not shown in the prior art, both from a structural and functional level. The more differences the better. It is better if the prior art is missing elements. It is best if the combination of elements that makes up the invention produce a synergy that leads to something unexpected.

From a purely legalistic standpoint, an invention is legally obvious, and therefore not patentable, if it would have been obvious to a person of ordinary skill at the time the patent application is filed. In the past this critical time for determining obviousness was at the time the invention was made, but since the U.S. became a first to file system the critical time for determining obviousness is no longer at the time of conception, but rather at the time of filing.

The framework used for determining obviousness is stated in Graham v. John Deere Co. While KSR is the most recent articulation of obviousness from the Supreme Court, it did not disturb the underlying Graham inquiry. Thus, every obviousness determination must first start with the Graham factors as the analytical tool. KSR is overlaid into the inquiry to provide the reasoning for reaching a particular decision based on consideration of the Graham factors.

Obviousness is a question of law based on underlying factual inquiries. The factual inquiries – the Graham factors – that make up the initial obviousness inquiry are as follows:

(1) Determining the scope and content of the prior art.

In determining the scope and content of the prior art, it is necessary to achieve a thorough understanding of the invention to understand what the inventor has invented. The scope of the claimed invention will be determined by giving the patent claims submitted the broadest reasonable interpretation consistent with the overall articulation of the invention.

(2) Ascertaining the differences between the claimed invention and the prior art.

Ascertaining the differences between the claimed invention and the prior art requires interpreting the claim language, and considering both the invention and the prior art as a whole.

(3) Resolving the level of ordinary skill in the pertinent art.

The person of ordinary skill in the art is a hypothetical person who is presumed to have known the relevant art at the time of the invention. It is necessary to determine who this hypothetical person is because the law requires that the invention not because the law – 35 USC 103 – seeks to determine whether “the differences between the subject matter sought to be patented and the prior art are such that the subject matter as a whole would have been obvious at the time the invention was made to a person having ordinary skill in the art…” So this hypothetical person of ordinary skill in the art is central to the inquiry.

Factors that may be considered in determining the level of ordinary skill in the art may include: (1) Type of problems encountered in the art; (2) prior art solutions to those problems; (3) rapidity with which innovations are made; (4) sophistication of the technology; and (5) educational level of active workers in the field. In a given case, every factor may not be present, and one or more factors may predominate.

A person of ordinary skill in the art is also a person of ordinary creativity, not an automaton. In many cases a person of ordinary skill will be able to fit the teachings of multiple patents together like pieces of a puzzle.

(4) Secondary considerations of non-obviousness.

In addition to the aforementioned factual inquiries, evidence that is sometimes referred to as ‘‘secondary considerations’’ or “objective indicia of non-obviousness,” must be considered. Essentially, secondary considerations are a reality check on the determination reached through the first 3 factual inquiries. In other words, the invention may appear on paper to be obvious, but if reality does not match theory then the invention can be established as being non-obvious.

Evidence of secondary considerations may include evidence of commercial success, long-felt but unsolved needs, failure of others, copying by the industry and unexpected results. If you are paying attention you notice that I mentioned unexpected results above. This is an important linchpin because unexpected results comes up as a secondary consideration and whether the combination of elements produces an predicted result or outcome plays a central role in the post-KSR obviousness determination.

It is important to understand that not all secondary considerations are created equally. For example, there are many possible reasons why a particular product may enjoy commercial success, such as a great marketing campaign or superior access to distribution channels. In those situations the invention itself is not responsible for the commercial success, rather there is something else at play. In order for commercial success to be useful there needs to be something typing commercial success to the innovation.

One particularly strong secondary consideration is long-felt but unresolved need. If there has been a well documented need or desire in an industry that has gone unanswered or unmet how is it intellectually honest to say that that a resulting solution is obvious? It wouldn’t be at all intellectually honest. That is why a long felt, well-documented need that becomes met is excellent evidence to demonstrate that an invention is non-obvious.

The evidence of secondary considerations may be included in the specification as filed, accompany the application on filing, or be provided to the patent examiner at some other point during the prosecution, which is probably the most common way to submit such evidence.

Before leaving the topic of secondary considerations it is worth noting, however, that just because your invention has never existed in the past does not in and of itself mean that it would be considered non-obvious. What makes a long felt, well-documented need so powerful is that the invention has never existed even as the industry has been searching for solutions. The key is not that it hasn’t existed, but that the invention hasn’t existed despite efforts to find a solution.

Conclusion

Now everything is clear, right? Sadly, no. This is just the beginning, but an important step in the overall process of understanding obviousness. The next step in the journey to understand obviousness needs to be When is an Invention Obvious? This article discusses the so-called KSR rationales, which we have only briefly touched upon in this article.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[[Advertisement]]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Ad-1-The-Invent-Patent-System™-1.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

22 comments so far.

Gary W.

December 8, 2015 10:01 pmYou want to know who, specifically, is a PHOSTA? The patent examiner. Really.

Anonymous

October 23, 2015 09:08 pmMany things are obvious, once you know them. Think “post-it notes”. . OBVIOUS!. And of course many things are obvious to the inventor, but not to a PHOSTA. As far as I’m concerned, if it’s useful, and nobody did it before . . It’s not obvious! PERIOD.

Anon

October 13, 2015 10:39 amMr. heller,

You seem quick to agree with Mike, but I do not think that you have comprehended what Mike wrote.

To wit: “Their “knowledge” is assumed to encompass anything they “might” have been exposed to in their art, which is the entire universe of public knowledge of the art.” (emphasis added)

The factors of how to apply that entire universe still must of course be “sussed” out – such factors as

(A) Determining the scope and content of the prior art; and

(B) Ascertaining the differences between the claimed invention and the prior art; and

(C) Resolving the level of ordinary skill in the pertinent art…

but the bottom line remains: the universe – the ENTIRE universe is to be taken into account as a starting position for the legal person that is PHOSITA – and this just does not “read out of” the law as you want to appear to claim.

Edward Heller

October 13, 2015 07:26 amMike, I agree with your post on Oct. 12, 4:46 p.m. Which is why I thought that there was something wrong with this: “The person of ordinary skill in the art is a hypothetical person who is presumed to have known the relevant art at the time of the invention.”

That is a direct quote from Gene.

Being available to and having actually knowledge of are two different things. Being available to require public availability. The problem to be solved tells one where to look. But the skill? A PHOSITA may not know that the inventive solution might work unless the art actually teaches him that it will. The less skill the PHOSITA, the more the art must teach.

On the other hand, the patent owner might defend by showing synergism even if there is a mild suggestion to combine. If the improvement was to a degree the art did not expect, patentable.

Mike

October 12, 2015 04:16 pmMr. Heller:

The definition is a “person having ordinary skill in the art”, not ordinary knowledge of the art. Their “knowledge” is assumed to encompass anything they “might” have been exposed to in their art, which is the entire universe of public knowledge of the art. The skill determines how they would interpret that knowledge and what conclusions they would have made based on that knowledge. If an ordinarily-skilled person knowing of two prior art references would not have been led to combine the two references to arrive at the applicant’s invention, then the invention is non-obvious over the combination of those two references. The inventor has added to the art.

Perhaps I overstated the case earlier. The PHOSITA does not need to be hyper-informed about every single reference that ever existed, he is simply a skilled worker in the field that has hypothetically been exposed to all of those references cited by the examiner in addition to the basic background knowledge required to be ordinarily skilled in the art. The fact that no one person may have ever been exposed to both of the references cited is not material, only the conclusions that he would have drawn had he been exposed.

Joachim Martillo

October 12, 2015 01:53 pmNed: I am not sure TSM is completely objective unless one is sure to distinguish combining ideas from combining implementations.

In computer networking in the 80s & 90s there were ideas for combining bridging and routing, but the implementations led down several distinct paths that actually taught away from each other.

Only after the combination of bridging and routing implementations (and not concepts) has been fully investigated, can one begin to analyze 103 obviousness.

Ned may actually be saying the above. I am not sure element refers to idea/concept or implementation.

Edward Heller

October 12, 2015 01:32 pmNight, we agree on TSM. If there is such a teaching, the claimed subject matter is known. No PHOSITA is involved. Completely objective.

Also, in absence of TSM, if all the elements were known and their combination brings no new functionality, i.e., synergism, it is not patentable. This too is a completely objective test that depends on test results or some showing of new functionality.

Patents are for something new or improved and not known. That is what these two tests give us. That is also what was in statutes in 1793.

Joachim Martillo

October 12, 2015 12:53 pmI am not sure the problem of arbitrary 103 rejections can be solved until secret Quality Assurance Systems are eliminated that give secret directives to reject a patent application or to cancel a patent by any argument no matter how vacuous.

There is evidence that patent examiners and APJs continue to attempt to make IP policy instead of executing the law. Obviously, such behavior violates 5 USC 132 and the APA, and in some of the most egregious cases may rise to a criminal STOCK act violation.

Thus, the first step to solving the 103 arbitrariness issues is removing any ability of the USPTO to claim confidentiality on any internal documents or databases.

Probably all PTAB deliberations should be videotaped even in camera, and all phone calls made by USPTO employees should be recorded.

Until the USPTO is forced to be totally transparent, 103 rejections will remain a tool to reject or to cancel as a matter of secret illicit policy (or corruption) and not as a matter of law.

Edward Heller

October 12, 2015 12:53 pmMike, well, if that IS the definition, then the definition reads PHOSITA out of the statute. That hypothetical PHOSITA would an expert in the art, just like the expert testifying about what would be obvious to one of ordinary skill.

Find real people of ordinary skill in any art and they do not know everything in the art, far from it. So, in a particular case, consider kid, out of school 4 years, MS Chem Eng., working a field of chemical processes of a specific type. He certainly does not know everything in that field. Far from it. So if the court agrees that he is the PHOSITA, it is not consistent to also say that he Knows all the art in that specific chemical process. An expert might. But not one of ordinary skill.

The whole system is nonsensical in the extreme. Truly. Whoever came up with it really screwed the patent system big time. I agree fully with Gene’s complaints. It is all subjective — essentially masking a seat of the pants call made by the trier of fact based on credibility of expert witnesses or something like that.

Such is not a good patent system.

Mike

October 12, 2015 12:12 pmMr. Heller:

The PHOSITA does, in fact, know all of the art, rather than just being a person who could search for it if she wants. I believe that is the point Anon is trying to make. An inventor is somebody who advances the art, who provides something that does not exist in the current art, and thus would not be obvious even to somebody who was omniscient in the state of the art. To be patentable, the invention must be an advance in the art, i.e., new and non-obvious to a hypothetical person who was aware of everything previously known in the art.

Paul Cole

October 12, 2015 10:02 amIt emerges from 19th century case law that if a group of features collectively produces a new result then they are a true combination, otherwise they are a mere aggregation. If the individual features are sticks, the new result is the twine that binds them together into a bundle. Otherwise, they can be simply picked up and removed one-by-one.

This test has been mischaracterised both in the UK and in the US for generations as pertaining to obviousness. If you think about it, however, it is actually a matter of construction – how at an overview level is the claim to be interpreted?

Provided that a new result can be shown, then TSM would normally be the most appropriate and valuable test.

Night Writer

October 11, 2015 08:20 pmI think Congress could pass a new 103 that makes TSM the standard for obviousness. That would give us a more objective test that would allow for greater quality.

Anon

October 11, 2015 07:35 pmOf course it does not, Mr. Heller.

Where do you get this “if he looks for it?”

The state of the art, (known, or knowable if searched) resolves to the same point.

At most, you are attempting some difference without a (legal) distinction.

I do not see the point that you are driving at.

Edward Heller

October 11, 2015 06:39 pmanon, of course it does, anon. The PHOSITA is charged with legal knowledge of the art in the sense that he can find it if he looks. He doesn’t KNOW it. The PHOSITA himself is something other that a person who knows all the art. Only an expert, a master, would KNOW the art.

Anon

October 11, 2015 02:26 pmI do not understand your reply Mr. Heller.

Of course you can define the legal person of PHOSITA as one who knows the art, and this does not remove PHOSITA from the statute – effectively or otherwise.

I am not sure that you are understanding what PHOSITA serves. This legal person is not a person for infringement. It is a person for patent grant.

Edward Heller

October 11, 2015 01:56 pmanon, it is the PHOSITA that is aware of the art and must decide obviousness. One cannot define who is a PHOSITA as a person who knows of the art. That effectively removes PHOSITA from the statute.

Anon

October 11, 2015 01:43 pmMr. heller,

Your statement of “Also, I do not think this can be correct, “The person of ordinary skill in the art is a hypothetical person who is presumed to have known the relevant art at the time of the invention.” A person who knows of all the art is an expert and everyone knows this.” is not in accord with black letter law.

It matters not if a real person would need to be omniscient to be able to actually gather all known (printed) matter at once in one location, no matter the location or language of the source material. PHOSITA is not meant to be a real person so it is a mistake to assume that such is or should be a real person.

Instead, the legal person that is PHOSITA is a “objective” standard of the state of the art reflecting all – and any – such matter that does exist at the time of invention.

I can only imagine that you do in fact know and recognize this aspect of black letter law, and that you were using hyperbole to try to make some different point. I am not clear what that point is though that you may have been attempting to make.

Paul,

Your insight lacks one critical component: judicial deference to what the patent system is meant to protect. If the judiciary is pre-disposed to limit the reach of patent protection, then any “weighing” will be skewed. In the US, this “deference” flows down from our highest Court and is currently decidedly anti-patent.

I do not believe it to be any sense of an accident that history has repeated itself and we find ourselves in a patent law situation that mirrors the birth of the Act of 1952.

Night Writer

October 11, 2015 10:06 amAlso, this new effect business is more witch burning. Patent law is very simple for the honest. There is structure recited in the claims. Find references that recite structure and reasons to combine. I have never seen a claim that needs any other type of analysis. (Maybe in all the history of the patent office there is one or two.)

As soon as you start trying to classify some of the structure as a witch (abstract, ineligible, etc.) you are no longer dealing with patent law but with politics.

Night Writer

October 11, 2015 10:04 amWell, I would amend this with Alice. When consulting with clients you have to tell them now that a judge may short-cut Graham and use Alice.

(Also, I do prosecution work at the EPO and USPTO. The EPO is no better at this. And, their technical solution is nothing but an eclectic collection of cases. Also, the US has something like 90 percent of the software business in the entire world. That is with patents and now we have people telling the EPO knows better, but Europe has not done as well as the US in innovation and with their two most progress countries the UK and Germany they would be at the end of the pack.)

Edward Heller

October 11, 2015 05:54 amGene, I agree that obviousness is subjective. Perhaps TSM should prevail unless the examiner or the validity challenger demonstrates that every element was known and their combination produces no new effect (per Paul Cole.)

Also, I do not think this can be correct, “The person of ordinary skill in the art is a hypothetical person who is presumed to have known the relevant art at the time of the invention.” A person who knows of all the art is an expert and everyone knows this.

So there is a flaw somewhere here. It is hard to pin it down, though. But it is another data point in the idea that the law of obvious is not law at all. When one has to balance a lot of factors, to weight them, and Paul Cole suggests, we are not in the realm of law anymore, but in the realm of equity.

Benny

October 11, 2015 05:37 amWhether an invention is obvious or not is a fairly subjective question. What should be obvious to the hypothetical PHOSITA is not necessarily obvious to the examiner who does not fully comprehend the prior art. I can provide examples.

Paul Cole

October 10, 2015 05:25 pmIf you look at the Graham test, all that it provides is a somewhat algorithmic approach to preliminary enquiries. When it comes to “make your mind up time”, however, the decision is left to the evidence and arguments of counsel. In the UK the leading test is in the Windsurfing case and has precisely the same structure and limitations.

What then do we have to work with? The answer, I believe, is a set of evidential boxes of weights, each weight representing a category of evidence (e.g. long felt want or teaching away) and the weights in each evidential box varying from large to small depending on the nature and strength of each party’s case. These weights are then placed in the scales of justice to enable a verdict to be reached.

It is impossible, under the legal systems of both our countries, to provide a more reasoned test because the statute does not provide for it. All we can do is to study the categories of evidential weight, and consider their relative importance in the overall decision because weights in some categories are more usually persuasive than the weights in other categories.

And as most important cases are finely balanced (otherwise they would not be litigated) the category of the decisive weight which tips the scales one way or the other varies fairly randomly from one case to another – it may be a surprising new effect or it may be outstanding commercial success which provides the compelling circumstantial evidence much discussed by the late Judge Rich. Sometimes it is to be found in admissions in research documents produced on discovery (I can point to at least two UK decisions where that was the decisive factor).

The only difference before the EPO is that it is essential to be able to point to a difference from the closest prior art from which new effect can be identified and a realistic technical problem can be reconstructed. But as a practical matter both in the UK and in the US if such a new effect cannot be identified, then it is at best very difficult for a patentee to succeed.

Technical problem has enabled the EPO to adopt a systematic and algorithmic approach to identifying inventive step which is practical and works. Unfortunately it is not foreseeable that either in the UK or the US a comparably practical approach will emerge any time soon.