In today’s technological environment, collaboration between different entities is commonplace, if not inevitable. That is, we are deep into the age of “Open Innovation” where companies use external ideas and technologies to accelerate their internal innovation and paths to market. Long gone are the days of “Closed Innovation” where companies suffered from NIH (“Not Invented Here”) syndrome and relied solely on their own personnel to develop new products and services.

In today’s technological environment, collaboration between different entities is commonplace, if not inevitable. That is, we are deep into the age of “Open Innovation” where companies use external ideas and technologies to accelerate their internal innovation and paths to market. Long gone are the days of “Closed Innovation” where companies suffered from NIH (“Not Invented Here”) syndrome and relied solely on their own personnel to develop new products and services.

Consequently, intellectual property (IP) law practitioners often find themselves drafting, reviewing and negotiating collaboration-type agreements. Invariably, the issue of who owns any resultant IP arises as this is usually the most contested issue in pre-collaboration discussions. Unfortunately, too often the answer is “we both do!” It seems the since-kindergarten, ingrained notion of sharing supersedes our B.S., M.S., J.D., Ph.D. and/or M.B.A. training in this respect! Pressures to “get the deal done” by our business and engineering clients, as well as the corporate lawyers who may be supporting the deal and always think it’s a good idea, result in IP law practitioners’ capitulation into drafting joint IP ownership clauses. We should have learned long ago, however, that while splitting the baby (i.e., joint IP ownership in this case) may sound “fair” and give us psychological comfort, in reality it is usually undesirable, unwieldy and perhaps unworkable.

Why Collaborate?

The often-cited danger of a company failing to embrace open innovation is the potential to miss out on great ideas because “not all of the smart people in our field work for us.” It is worth noting, however, that the danger is broader than good product ideas coming from other, and often non-competitor (i.e., vendor or supplier) companies. That is, good ideas can come from the end-user, consumer of a company’s products or services. This is what is known as “user innovation.” This dawned on me while reading a recent Los Angeles Times article illustrating that following a closed innovation model, where outside submitted ideas receive automatic “no thank you, we didn’t read it and here it is back” letters, has the danger of losing customer loyalty and engagement – two psychological factors that lead to increased and continued sales!

Aside from the realities and benefits of open (and user) innovation, the issue of joint IP ownership also arises frequently is run-of-the-mill supplier and vendor relationships. This is especially true when a company attempts to source products or services that are not strictly “off the shelf” such that the supplier has to perform some level of innovation in order to produce the deliverables called for in the relevant agreement. In such situations, the standard “work made for hire” contracting clauses are typically rejected by the vendor/supplier and again the since-kindergarten, ingrained notion of sharing and fairness leads to situations of joint IP ownership.

In sum, regardless of the title of the agreement involved – Joint Research Agreement, Technology Cooperation Agreement, Joint Development Agreement, Sponsored Research Agreement, Development Agreement, Supply Agreement, Services Agreement, etc. – they happen and the opportunities to appease both sides and settle upon joint IP ownership terms abound!

What is Joint IP Ownership?

To make sure we are all on the same page, I quote the European Commission’s Executive Agency for Competitiveness and Innovation (EACI), which eloquently defines “IP joint ownership” as follows:

[A] situation in which two or more [entities] have proprietary shares of an asset: they co-own a property. Joint ownership of IP, in particular, frequently arises in collaborative projects when the results – usually called foreground [IP] – have been jointly generated with other collaboration partners and the share of work is not easily ascertainable.

And, because joint IP ownership under a collaboration agreement often depends on whether personnel from the different parties actually “jointly generated” the foreground IP in question, U.S. Patent Law is instructive on when persons may be considered “joint inventors”:

Inventors may apply for a patent jointly even though (1) they did not physically work together or at the same time, (2) each did not make the same type or amount of contribution, or (3) each did not make a contribution to the subject matter of every claim of the patent.

Joint IP Ownership Scenarios

So, as parties enter into collaboration-type agreements, how do they end up in joint IP ownership scenarios? The ownership of the resultant IP that arises from the collaboration (i.e., the “foreground IP”) is usually the second issue that is discussed – right after what specific IP is each party bringing to the table (i.e., the “background IP”) that prompted the parties to even contemplate collaborating in the first place! As mentioned above, however, this second issue is usually the most contested issue in pre-collaboration discussions.

In many situations, joint IP ownership can be avoided altogether. That is, questions of ownership of foreground IP can be resolved by one party owning the IP – typically, the party that contributes the most background IP, funding, facilities and/or other resources, while the other party receives a limited, non-exclusive license. This is especially true when dealing with supplier-type collaboration agreements. But, when the parties have equal bargaining power, the joint IP ownership negotiations begin.

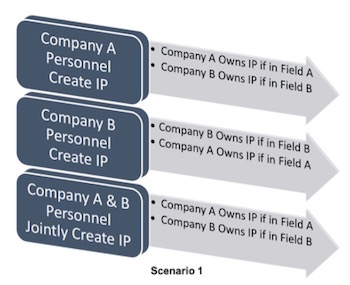

During the course of negotiations, two parties presumably working in distinct fields may start with a “we will not create any joint IP” posture. This is what is illustrated in Scenario 1 – where Company A will own all inventions in Field A and Company B will own all inventions in Field B, regardless of inventorship. This “by field” approach is simple to draft and avoids any joint IP ownership, but can be complicated in practice. Why? Well, what if the foreground IP cannot be neatly fitted into “Field A” or “Field B”!? After all, when smart people put their heads together, innovation happens! Or, what if the foreground IP is neither in Field A, nor in Field B!? Drafting an agreement where ambiguity will surely arise is obviously not a “best practice” to which any IP practitioner would aspire.

During the course of negotiations, two parties presumably working in distinct fields may start with a “we will not create any joint IP” posture. This is what is illustrated in Scenario 1 – where Company A will own all inventions in Field A and Company B will own all inventions in Field B, regardless of inventorship. This “by field” approach is simple to draft and avoids any joint IP ownership, but can be complicated in practice. Why? Well, what if the foreground IP cannot be neatly fitted into “Field A” or “Field B”!? After all, when smart people put their heads together, innovation happens! Or, what if the foreground IP is neither in Field A, nor in Field B!? Drafting an agreement where ambiguity will surely arise is obviously not a “best practice” to which any IP practitioner would aspire.

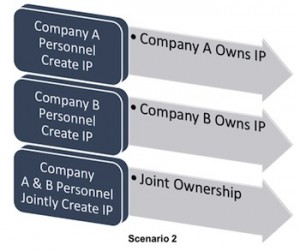

Thus, the negotiations may then move on to Scenario 2 – a “by inventorship” approach that fallaciously sounds fair because each party owns what their personnel invent and, if there is mixed inventorship, there is joint IP ownership. Again, this ownership clause is easy to draft and sounds “fair.” In this situation, however, what if personnel from Company A improve background IP of Company B, and the resultant foreground IP is clearly in Field B? In this situation (and vice versa), a company enters into a collaboration but will not own improvements to their background IP which the other company may not have the expertise to bring to market (or even care about)!

Thus, the negotiations may then move on to Scenario 2 – a “by inventorship” approach that fallaciously sounds fair because each party owns what their personnel invent and, if there is mixed inventorship, there is joint IP ownership. Again, this ownership clause is easy to draft and sounds “fair.” In this situation, however, what if personnel from Company A improve background IP of Company B, and the resultant foreground IP is clearly in Field B? In this situation (and vice versa), a company enters into a collaboration but will not own improvements to their background IP which the other company may not have the expertise to bring to market (or even care about)!

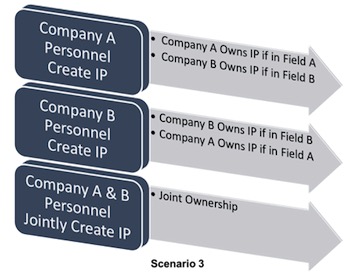

Next, the negotiations may move on the Scenario 3—a hybrid “by field and inventorship” approach where each party owns any foreground IP in their respective fields that is singularly created, but co-own any jointly-created IP regardless of field. This approach inherits the “best of both worlds” (i.e., Scenarios 1 and 2), but obviously also inherits the worse of those worlds as well.

Next, the negotiations may move on the Scenario 3—a hybrid “by field and inventorship” approach where each party owns any foreground IP in their respective fields that is singularly created, but co-own any jointly-created IP regardless of field. This approach inherits the “best of both worlds” (i.e., Scenarios 1 and 2), but obviously also inherits the worse of those worlds as well.

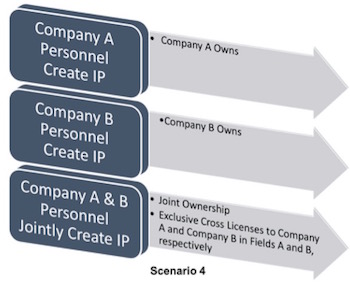

Finally, the parties may arrive at a clever solution shown in Scenario 4 – a seemingly “by inventorship” approach similar to Scenario 2 where each party owns any foreground IP that their personnel create singularly, but co-own any jointly-created IP regardless of the field. The wrinkle here, however, is that jointly owned IP is exclusively cross-licensed to each party in their respective fields to overcome the disadvantages disclosed above.

As you can imagine, there are countless permutations and variations of the above-presented scenarios. (An excellent video explaining some of these scenarios can be found here.) For example, a hybrid of Scenarios 3 and 4 may be even “more fair” to the parties involved depending on the fields, relevant negotiation power, amount of R&D funding, and amount of background IP each party brings to the table. The point here, however, is that solving what seems to be a fair allocation of foreground IP (i.e., how to split the baby) amongst the parties is only half the battle!

The Major Unaddressed Issues that Arise

Imagine, for a minute, a divorce where each parent’s attorney agrees to joint custody of a minor child. Okay, great! But is that it!? Who gets Thanksgiving and who gets Christmas!? Who even decides if the child celebrates Christmas versus Hanukah? When does the child live with which parent? Who pays for private school, braces and piano lessons? It sounds silly not to resolve those issues at the time of negotiating the divorce agreement, right!? But that’s exactly what happens in many collaboration-type agreements with respect to joint IP ownership! What happens to the offspring – the jointly-created, foreground IP – when the agreement expires or is (acrimoniously) terminated, and the parties go their separate ways!?

It is one thing to define what foreground IP (or “Project IP”) actually becomes “Joint IP.” Nearly every agreement does that, at a bare minimum, with some variation of the scenarios presented above. The problem arises, however, when that is all that is addressed. Often, the parties and their respective attorneys fail to fully bake the scheme by not addressing the consequences and mechanics of such joint ownership for a variety of reasons ranging from ignorance to misunderstanding. A complete collaboration-type agreement should, however, address the following consequences and mechanics resulting from joint IP born as a result of the collaborators’ relationship:

- Who decides the form of IP protection (design, utility, trade secret and/or copyright)?

- Who pays for any IP filings?

- Who directs prosecution of any IP filings?

- Who decides in which jurisdictions such IP filings are made?

- Who can enforce the IP?

- Who can license the IP to whom?

- Who can alienate or pledge the IP?

- Who gets any royalties earned as a result of licensing the IP?

- Who can practice the IP, and in what field(s)?

These issues are in addition to any tax consequences, reporting requirements, audit provisions and conflict resolution procedures needed to properly give effect to the collaboration-type agreement’s joint IP ownership clause, thereby addressing the most likely uncertainties that will arise during (and post) the collaboration. This is not about turning a 10-page agreement into a 15-pager for C.Y.A. purposes. Rather, this is about addressing time-tested situations that WILL arise!

CLICK TO CONTINUE READING. Next is a look at the danger of not addressing these issues and thus, relying on the “default” law of joint IP ownership in various jurisdictions.

____________

This article reflects the author’s current personal views and should not necessarily be attributed to his current or former employers, or their respective clients or customers. The author would like thank James Cross, Young-Wook Ha, Ira Hatton, Esther H. Lim, John M. Neclerio, Akihiko Okuno, Michael Ray, Denis Schertenleib and Liina Tonisson for their assistance in completing the summary law table included herein. The “dual light bulb” picture, modified by the author, is used courtesy of Ramon Vullings.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IP-Copilot-Apr-16-2024-sidebar-700x500-scaled-1.jpeg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

3 comments so far.

Frank Sudia

February 20, 2016 10:05 amPresumably the above agreements at least get you past the non common obviousness problem, but what about inter dependence? If co1 owns a core idea & co2 owns the good improvement, you’re back to a total mess again.

Paul F, Morgan

February 17, 2016 10:14 amAnother problem with joint ownership of inventions: Potential alleged conflicts of interest and client representation in PTO prosecution decisions, which could even lead to malpractice accusations.

P.S. There are many good points made in this article. It is an important topic because these issues are amazingly often ignored by University an corporate contract administrators. That has gone on for a long time, E.g. “Joint Ownership” of Inventions, Patents or Copyrights – A Legal mess to Avoid” December 1997 AUTM Newsletter [The Association of University Technology Managers.]

Paul F, Morgan

February 17, 2016 10:01 amUnless I missed it, this is missing vital explanations the really serious legal problems: either joint owner can do anything they want with the patent w/o any sharing or accounting in the U.S., including competitively low bidding each other for licensing. Yet enforcement of patents jointly owned requires BOTH owners to be parties to the suit. [If either party refuses to join, the suit cannot proceed.]