The original First Action interview (FAI) Pilot Program went into effect in 2008. Because of the success of the program, it was extended into two additional pilots since and remains open today. The FAI program requires an applicant to conduct an interview with the examiner early in prosecution. To enter the FAI program, an applicant must file a request form prior to receiving a first office action on the merits (FOAM). The program is free, but the application must include no more than 20 total claims and no more than 3 independent claims up until the time at which the requisite interview is conducted.

The original First Action interview (FAI) Pilot Program went into effect in 2008. Because of the success of the program, it was extended into two additional pilots since and remains open today. The FAI program requires an applicant to conduct an interview with the examiner early in prosecution. To enter the FAI program, an applicant must file a request form prior to receiving a first office action on the merits (FOAM). The program is free, but the application must include no more than 20 total claims and no more than 3 independent claims up until the time at which the requisite interview is conducted.

FAI Program Overview

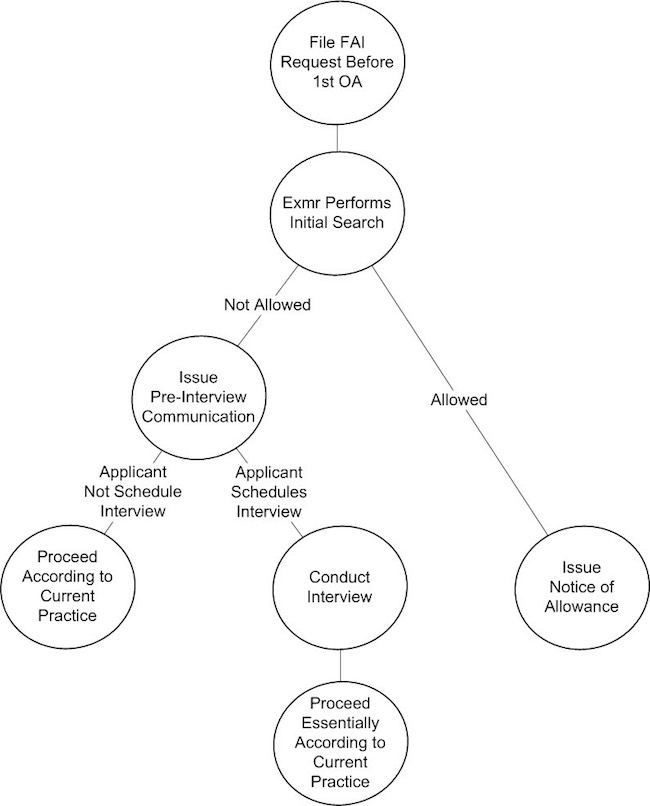

Figure 1 illustrates the structure of the FAI program. The examiner performs an initial search. If the examiner determines that the claims are not yet allowable a brief Pre-Interview Communication is completed that identifies particular references (and pertinent paragraphs or portions therein) and rejection types. The Pre-Interview Communication looks very similar to a PCT search report in detail and format. An applicant has one month to file a responsive Interview Request form with an agenda and/or proposed amendment. The interview is then conducted, after which the examiner can either allow the application or issue a First Action Interview Office Action Summary. Frequently (though not always), this document mirrors the content from the Pre-Interview Communication along with an interview summary. The applicant then has two months to respond to the Office Action Summary and prosecution continues as normal (as though the Office Action Summary was a first Office Action).

Thus, FAI program affords applicants a no-fee opportunity to speak with examiners early during prosecution, before the examiner has invested the time to prepare a complete Office Action. There are two common concerns surrounding this program. A first is that claims must be limited in number (even though the claim set can be later expanded after the pre-action interview), and a second is that it can be difficult to fully understand how the examiner is interpreting the claims and/or references in the brief Pre-Interview Communication.

We set forth to characterize the use and results of this program. We submitted a Freedom of Information Act request to the USPTO, requesting data for each published utility application for which a FAI request was granted. Particularly, the data fields requested were the application number, filing date, examiner, status, patent issuance date (if applicable) and number of office actions issued. Subsequently, for each of these applications, we obtained data for the examiner from LexisNexis® PatentAdvisorSM analytics tool. The examiner data included the average number of office actions issued per patent by the examiner, the average time between filing and patent issuance for the examiner, and the examiner’s allowance rate.

[Varsity-1]

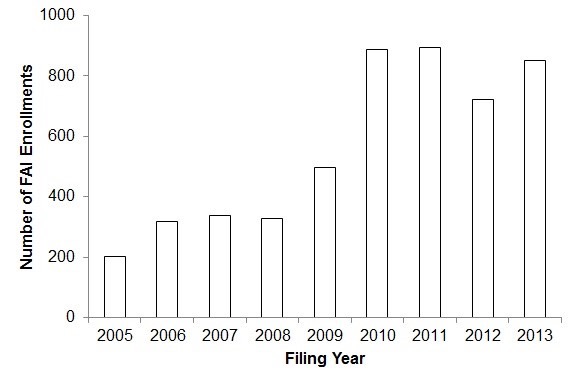

(Un)Popularity of FAI Program

Perhaps for one or the other of these reasons, or perhaps due to practitioners’ unfamiliarity with this program, very few applicants have requested to participate in the FAI program. We binned the published applications identified by the USPTO as having a granted FAI request by the calendar filing year. As shown in Figure 2, each calendar filing year is associated with fewer than 1,000 applications for which FAI requests were filed and granted. Meanwhile, approximately a half a million utility applications have been filed during each year.[1] Thus, only approximately 0.16% of applicants are using this program.

Favorable Prosecution Results of FAI Program

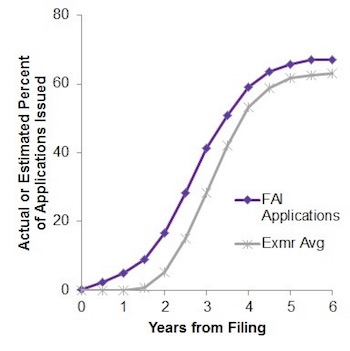

Two prosecution statistics are usually of high interest to applicants relate to prosecution success rates and prosecution speed. Our analysis represented in Figure 3 speaks to both of these variables. Specifically, we used our data set to determine, for each of various time period, what fraction of the applications (for which the time period had elapsed) were patented within the designated period. For example, for a 2-year data period, we first identified a set of FAI applications for which it had been at least two years since the filing date, and we then determined what fraction of that set issued as a patent within two years or less.

The FAI allowance percentage saturates at about 5 years from filing at a 66% allowance rate. The midpoint of the curve (at which half of the allowance rate was reached) was 2 years, 8 months. (See Figure 3, purple line.)

For comparison, we similarly assessed the average time between filing and issuance for the examiners represented in our data set. For example, considering the 2-year-date point, we again identified the set of FAI applications for which it had been at least two years since the filing date, and we then determined what fraction of that set were assigned to an examiner with an average filing-to-issuance time period that was two years of less. We normalized the complete time series by the examiners’ average allowance rate, which was 63%.

This normalization factor is also the curve’s saturate allowance rate by definition (63%). The midpoint of the curve was 3 years, 1 month. (See Figure 3, gray line.)

Thus, the allowance rate of FAI applications was slightly higher than that of the corresponding examiners (66% versus 63%). Further, the prosecution speed was faster (as the allowance midpoint was reached 5 months faster for FAI applications).

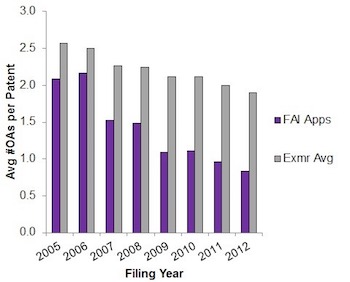

This difference in timescales suggest that a difference in Office Action counts may also be observed. Thus, we grouped applications again by filing year and identified the FAI applications which were issued. We then identified the average number of office actions issued across the set. We also identified, for each application in the set, the average number of office actions issued per patent and averaged these values to use as a control.

Figure 4 shows that FAI applications are likely to have issued after fewer office actions than normal for each examiner. We note that a bias is present during recent years, as the data sets are biased to including FAI applications issuing after few office actions (as there would not have been sufficient time for issuances after many office actions to be represented). However, we believe this bias is very small for years before 2010, as 96% or more of the applications from each of these years have reached their finial disposals (so it is less likely that many new issuances would be adjusting the data). In 2005, 99% of the applications have reached their final disposals.

Conclusion

Two years ago, we published one of the first articles to quantify the efficacy of the First-Action Interview Pilot Program.[2] The USPTO also has regularly reported that first-action allowances in the FAI program far exceed those within the regular application pool.[3] Here, we show that the prosecution benefits of this program continue to be realized and that the program improves both the efficacy (allowance rate) and efficiency (office-action counts and time to issuance) of prosecution.

However, to our bewilderment, very few applicants are engaging in this program – a free FAI request is filed in a mere 1 of 625 applications. We can identify two instances in which we consider a decision not to enter the FAI program to be justified. The first is if an applicant desires inefficient prosecution, as may be the case where a pharmaceutical applicant is seeking long patent term adjustments. The second is if an applicant is seeking a restriction requirement or files large claim sets and thus feels compelled to submit a claim set with more than three independent claims and/or more than twenty total claims (also likely to involve an applicant prioritizing patent term adjustments).

We believe that all other applicants should be entering this program given the clear advantage and cost effectiveness. Other frequently voiced concerns of the program are easily addressed. Specifically, claim sets can be extended beyond the three-independent, twenty-total limit following the first office action, and most examiners will even allow such expansion after the pre-action interview if it is expanded in a manner that does not include new substantive limitations or substantially broader scope. Further, any applicant confusion suffered due to the brevity of the Pre-Action Communications is resolvable during the interview. The pre-action interview is a means through which the applicant can explain the invention and context while the examiner can explain his or her confusions or skepticism before examination is fully commenced. This initial dialogue should, and empirically does, facilitate compact prosecution.

There is a common saying that “A picture is worth a thousand words.” We believe that a verbal conversation is worth many paper communications and the data demonstrates the effectiveness of an interview. Having the opportunity to explain one’s invention to an examiner and to understand the examiner’s interpretations and opinions of the invention is invaluable early in prosecution. Through the FAI program, the USPTO is providing applicants with the ability to benefit from this initial discussion early during prosecution, before the examiner calcifies their rejection strategy or applicant becomes frustrated in response to different understandings or interpretations.

We have seen, both in our professional experiences and through these statistics, such great benefit of this program that we have encouraged the USPTO to take this program one step further and establish a Pre-Search Interview Program that would allow the applicant to explain and potentially demonstrate an invention even prior to the examiner conducting a search.[4] We believe that this type of interview would even further improve the efficiency of prosecution. Additionally, having the examiner available for an in-person interview at an applicant’s discretion aids in quickly understanding the issues and keeping prosecution compact.

In conclusion, we encourage all practitioners (who are not seeking patent term adjustments or restriction requirements) to participate in the FAI program. Effective and efficient prosecution is the norm for this free program that reduces the cost and time delay associated in the patent process.

_______________

[1] United States Patent and Trademark Office. Performance and Accountability Report (2014).

[2] Kate Gaudry, A Look at the Results of USPTO’s Interview Program, Law360, Jan. 9, 2014.

[3] U.S. Patent & Trademark Office, Data Visualization Center.

[4] Email from Kate Gaudry, to U.S. Patent & Trademark Office (May 6, 2015).

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

7 comments so far.

Marj Scariati

April 4, 2016 09:40 amWow “Easy peasy”, that is quite an offensive comment, and totally wrong to boot. What can be gleaned from the above comments is that in actual practice, the program often does not work effectively due to shortcomings in the program, not due to any lack of ability on the part of the practitioners.

Easy peasy

April 1, 2016 06:49 pmI think we can glean from the above discussion that those that know what they’re doing can make the program work well to their advantage, but those that don’t know what they’re doing have a super hard time making everything work out. Looks like it depends on the skill of the attorney and ease of the case as to whether or not the program works to your favor.

Philip Hunt

March 31, 2016 07:16 pmAuthors Gaudry and Franklin say “Further, any applicant confusion suffered due to the brevity of the Pre-Action Communications is resolvable during the interview.”

That has not been my experience. My experience is that the examiner has conducted a search until they find some art and have a hunch they can make a good rejection. The communication then just lists the art to be used and the type of rejection. No reasoning given. The interview does not provide any clarification because until the examiner has writing out their reasoning, they only have a vague notion of what it will be.

I suppose the FAI would be useful in cases where your clients are noble prize candidates that are so far ahead of everybody that the examiner has difficultly understanding what the invention is, but once they do, there is no prior art anywhere near it, so straight you go to allowances. For most of us, that is not the case. For most applications I do, the main difficultly is not getting the examiner to understand the invention, it is finding what the broadest claims that can be had in light of the prior art. For that, I find it is better to have the examiner do a complete search and put all their rejections with reasoning down in writing. Then I have something to work with.

Philip Hunt

March 31, 2016 05:58 pmWhen this pilot program first came out, I routinely put in for FAI. After going through the first 2 or 3 FAIs, I came to the same conclusion the other three posters did – the FAI was so vague that you effective did not learn the examiner’s real reasoning for rejection until the second (and usually final) office action. A waste of my time and my client’s money. Fortunately, the USPTO examiners also did not seem like this program or realized it was a disservice to the applicants. After the first 2 or 3 the examiner would call and asked if I really want to go through with it. I would tell them no and that would be the end of it.

Marj Scariati

March 31, 2016 09:52 amWhile it sounds like a great idea in theory, in practice I have seen little benefit to this program, and more detriment in its use.

The pre-action communication is often too cryptic to be able to prepare a meaningful response to discuss with the Examiner. As a result, the first OA typically just repeats it, but now there is a shortened period of response of 2 months vs. the usual 3, and after having no choice but to respond in similar fashion, the next OA is generally made Final. Also, if you do not respond to the pre-interview communication because it is not sufficiently fleshed out by the examiner in order to do so properly, or because the 1-mo period for response is not sufficient due to client delays in receiving instructions, vacation schedules etc., the first OA then comes with a shortened 2-month period for response and is equally cryptic.

From my experience, the program most often leads to the payment of additional extension fees and a quicker final rejection and not much else.

Mark Summerfield

March 30, 2016 08:48 amI used the FAI program once, and would never do so again!

The big problem (in my case, anyway) is that the First Action Interview Summary takes the place of a full first Office Action. If there are substantive issues outstanding that cannot be addressed through the interview/response process, your next Office Action is likely to be made final. And this is then the first time you have seen the examiner’s full reasons for rejection set down on the record.

At this stage, you are pretty much committed to filing an RCE in order to submit your first full response to your first fully-reasoned Office Action.

Unless you are really confident that your case is one that will go straight to allowance, or will have only relatively straightforward issues to be addressed following the interview, I cannot recommend the FAI program based on my experience.

Perhaps this is the reason it has been so “under-utilized”? In which case, the apparent benefits may be due to selection bias?

Mark

David Nay

March 30, 2016 08:02 amI have participated in this program numerous times, and have had varying success. When it works, and both parties approach it was a collaborative mindset, it works very well. In most cases, however, it amounts to a wasted office action.

I feel that the policy of simply changing the title of the search report from “pre-action communication” to “first office action” does a great disservice to my clients. I have had several cases where the supposed first office action still tells me how the Examiner “plans to” reject the claims, though provides no detail that actually amounts to a rejection. Because the first office action is identical to the pre-interview comm, I’m inclined to respond in a similar way as I did to the pre-interview communication, which then puts me under final before the Examiner is required to clearly articulate the basis for the rejection.

The process needs to be reformed so that the first action (if allowance is not obtained via the interview) is an ACTUAL office action and not merely a parroted short-form summary that walks the line of the minimum statutory requirements. If that change was made, I would enroll my entire docket.