Standards Development Organizations (SDOs) usually require that companies participating in creating the standard commit to license their essential patents on “reasonable and non-discriminatory” (RAND) terms and conditions, although they don’t specify what RAND means exactly. Some require “fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory” (FRAND) terms and conditions, but that is similarly vaguely defined. In practice, RAND and FRAND are synonyms.

Standards Development Organizations (SDOs) usually require that companies participating in creating the standard commit to license their essential patents on “reasonable and non-discriminatory” (RAND) terms and conditions, although they don’t specify what RAND means exactly. Some require “fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory” (FRAND) terms and conditions, but that is similarly vaguely defined. In practice, RAND and FRAND are synonyms.

The debate on RAND terms and conditions is mostly about the reasonability of the royalty rate, less about non-discriminatory part. So, what is a “reasonable rate”? Companies that manufacture products based on a standard will demand lower rates or royalty-free licenses, claim harm from patent hold-ups and from royalty stacking. These companies will argue that it is unfair when companies that contribute technology to the standard benefit from the lock-in of the standard because it is now unavoidable to use the essential patents in their products. On the other hand, companies that participated in standards development, and own essential patents because of that investment, claim that lower royalty rates will remove the incentives for future investments in standard setting and will stifle innovation.

In the confusion generated by these lobbying interest groups, it makes sense to go back to the one thing everyone seems to agree on: Standards are good.

Regulatory standards (regulating, for example, product safety) protect consumers and create a level playing field for manufacturers. Interface standards (such as, for example, GSM, Wi-Fi, DVD) promote competition by opening up eco-systems, they lower costs by increased sales volume, and deliver more choice for consumers.

The purpose of RAND

SDOs use the intellectual property rules in their bylaws to make it attractive for companies to participate and to avoid problems with their patents later on. Potential problems are, for example:

- A company contributes patented ideas to the standard, and then refuses to license them when the standard is finished. This creates a monopoly for the patent owner on the use of the standard and locks out other companies that contributed to the creation of the standard. Or it creates deadlock, preventing everyone from using the standard, when several companies refuse to license their patents.

- A company contributes patented ideas to the standard, and then licenses these patents with a royalty rate that makes it commercially unattractive for other companies to use the standard in their products. The effect is the same as a refusal to license patents.

Participation in standardization activities is a huge investment for the participating companies. The development of the technical specification usually takes several years and participation will cost between a hundred thousand US$ and couple of million US$ in engineering resources. When you include the cost of prototyping and product development the costs are even higher.

It is an unacceptable risk for participants to find themselves blocked from using the standard when one of the participants refuses to make essential patents available, or makes them available against terms and conditions that make no commercial sense.

The SDO therefore requires that participants commit to license their essential patents and that they ask a ‘reasonable’ royalty rate. Without that commitment from all participants, many companies will find it unattractive to contribute engineering resources to create the standard.

RAND-RF instead of RAND

Some SDOs oblige participating companies to promise that they will license their essential patents royalty free. This variant is called RAND-RF or RAND-ZERO. RAND-RF is obviously attractive to companies that use the standard, but can make it unattractive for patent owners to make their technology available for inclusion in the standard. It is a balancing act. The standard may not achieve the optimal technical solution with a RAND-RF IPR policy. It will depend on the expertise of the participating companies and the difficulty of the technology.

Bluetooth is an example of a standard with a RAND-RF license obligation (section 5 of the Bluetooth Patent/Copyright License Agreement).

Companies with a high market share in the relevant market tend to prefer royalty-free licensing obligations, even when they themselves contribute patented technology to the standard. Because of their high market share, they would pay more royalties than they receive from others. They can also recoup their investment in standardization more easily from selling products. For companies with a smaller market share, the additional operation margin that license income will provide is often needed to justify a contribution to standards development. These companies tend to prefer a RAND license policy.

What is a reasonable rate? A balancing act.

Companies that invest in creating the standard have two ways to recoup that investment: By selling products that use the standard, and by collecting royalties from other companies that use the standard.

SDOs with a RAND licensing policy enable both methods. SDOs can choose RAND-RF when the participants don’t want to enable royalty collection.

The two methods enabled by RAND licensing policy can be contradictory. As pointed out before, increasing the royalty rate can make the products too expensive for potential customers, reducing the sales of products that implement the standard. Lowering the royalty rate on the other hand may increase the number of products that can be sold, but will also reduce the license income for the companies that rely on licensing to recoup their investment.

Hence the balancing act. It is in the interest of everyone that the standard is successful. The point of making a standard is to get it widely adopted. That means the combined royalty rate, for all essential patents, should not get in the way of adoption.

That still sounds pretty vague, but it creates the opening to apply an economic analysis of the effect of royalty rates on the adoption of a standard. With a simple micro-economics analysis on the adoption of standards we can achieve a surprisingly accurate answer.

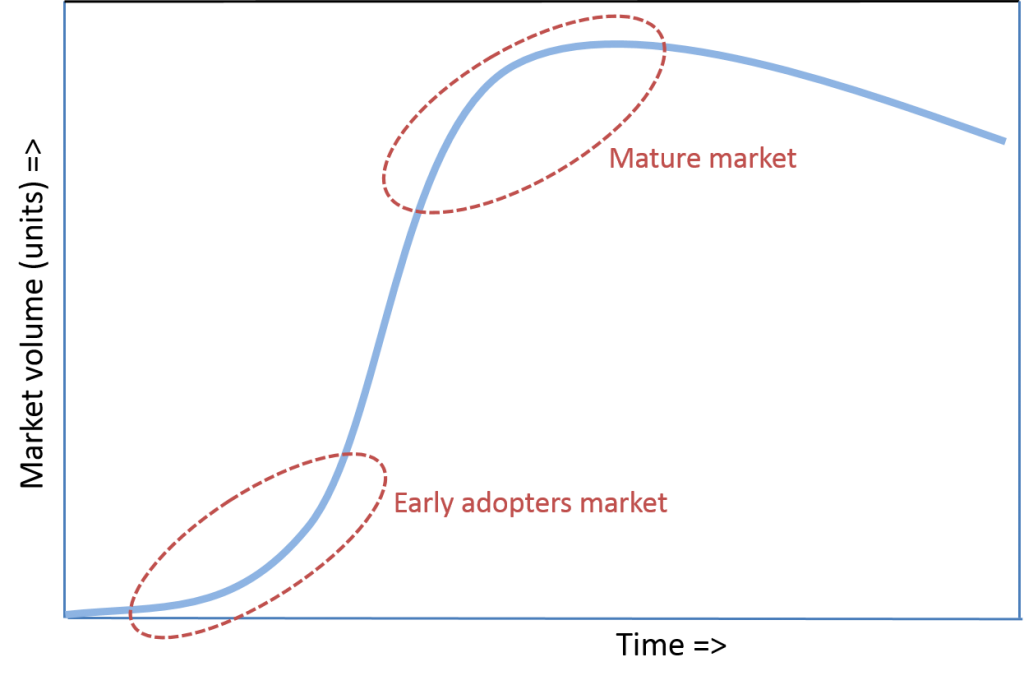

The adoption of interface standards (GSM, Wi-Fi, DVD, etc.) follows the typical adoption curve for new products and new product features. After an initial period of slow adoption, successful standards exhibit a period of rapid growth, until the market saturates and finally declines.

What is reasonable in the early adoption phase?

For new interface standards, the growth of the market usually depends critically on two factors:

- The perceived value (determined by consumer awareness of the benefits of the new standard)

- The price consumers have to pay to enjoy the feature (determined for a large part by the cost of implementing the product feature enabled by the standard).

An increase in sales volume will drive down cost. An increase in sales volume will also makes it worthwhile for manufacturers to advertise the benefits of the new standard. This creates a positive feedback loop that gradually drives down costs, and increases consumer awareness until the market saturates.

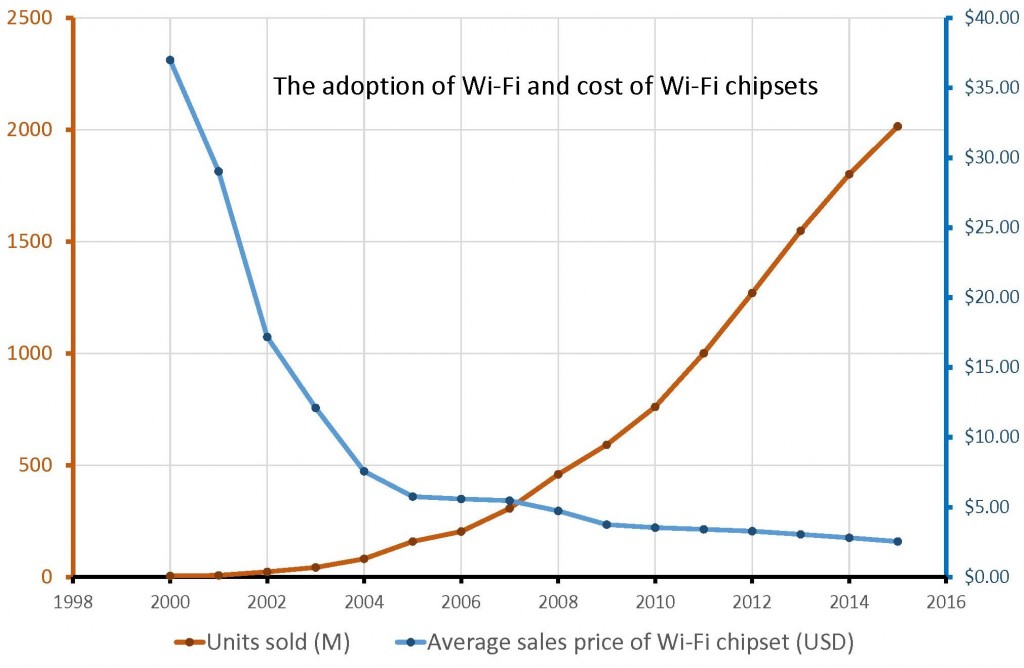

The correlation between price and growth is clearly visible in this report from ABI research quoted by the court in Innovation IP Ventures vs Multiple Defendants, page 78Innovation IP Ventures vs Multiple Defendants, page 78.

When the royalty rate cannot be zero we need a rate that does not significantly impact adoption as reasonable compromise between the interests of all stakeholders. Before we proceed to analyze what constitutes a ‘significant’ impact, we need to make two observations.

When the royalty rate cannot be zero we need a rate that does not significantly impact adoption as reasonable compromise between the interests of all stakeholders. Before we proceed to analyze what constitutes a ‘significant’ impact, we need to make two observations.

The first observation is that we cannot limit our analysis to the royalty rate of a single essential patent. We need to consider the impact of the sum of the royalty rates for all patents that are essential to implement the standard. Let’s call that royalty rate the “cumulative rate”. The impact of the royalty on a single essential patent may be insignificant, but when there are thousands of essential patents, the sum of insignificant impacts can still be significant. That is what is referred to as “royalty stacking”.

The second observation is that many products have other features beside the new standard. Smartphones, for example, implement many standards. When you add a new standard to a smartphone you need to look at the influence of royalty collection at the adoption rate of the new feature, not at the adoption rate of smartphones. The adoption of a new feature in a smartphone is influenced by the additional price the smartphone manufacturers charge for the new feature. This complicates the analysis because manufacturers tend not to publish the additional price of individual product features, only the complete price of a product.

Instead of looking at consumer sales prices we can also look at the cost of implementing the feature in a product. The cost of implementing the feature in a product depends on the cost of additional components (called Bill Of Material or simply BOM) as well as the engineering cost to develop the product. For high-volume electronics products, the cost of the BOM usually dominates.

We are now ready for a quantitative analysis of the impact of royalty payments on the adoption of new standards during the early adopters stage. The following thought experiment shows how the effect can be quantified.

Suppose a patent pool for Wi-Fi patents was created in 2004, licensing all standard essential patents at 10% of the component cost (the number 10% is chosen here to make the calculation easier). The table above shows that the price decline of Wi-Fi chipsets was 40%-25% per year in the years 2003-2005. If we assume that sales volume only depends on price (not correct, but a worst case assumption), a royalty of 10% of the BOM would have slowed the price decline with 3-6 months. In practice the delay would be less because price is only one factor in standards adoption, the increase in consumer awareness of the standard is a significant other factor. Is a 3-6 month delay in adoption a significant impact? That is still open for debate, but at least we have quantified the effect.

Note that the profitability of the chipmakers is not impacted by royalty payments. Assuming all competing chipmakers pay the same royalty, they can simply lower their chip price a bit later than they would have done otherwise. When royalty rates are the same for everyone, royalties can be considered part of the product’s BOM.

There have been attempts to determine what is reasonable on the basis of profits made on the sales of products that implement the standard. That is problematic because the profitability of a product is notoriously difficult to determine objectively. Furthermore, manufacturers may even deliberately sell products at a loss when they fight for market share in a growth market. Would a loss making industry be exempt from paying royalties on essential patents?

The cost of components is much more easily determined objectively. That’s why studying the effect of an increase in BOM cost on the adoption of the standard can be a practical method to determine what a reasonable royalty rate is. For standards in the early adopters phase that is. For mature markets the effect of royalty collection on the market is very different.

What is reasonable in a mature market?

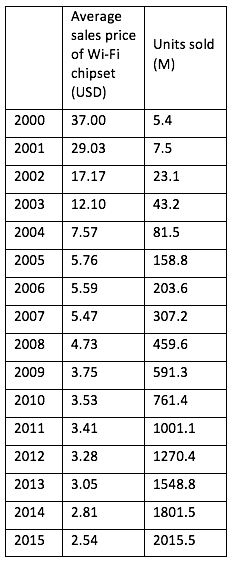

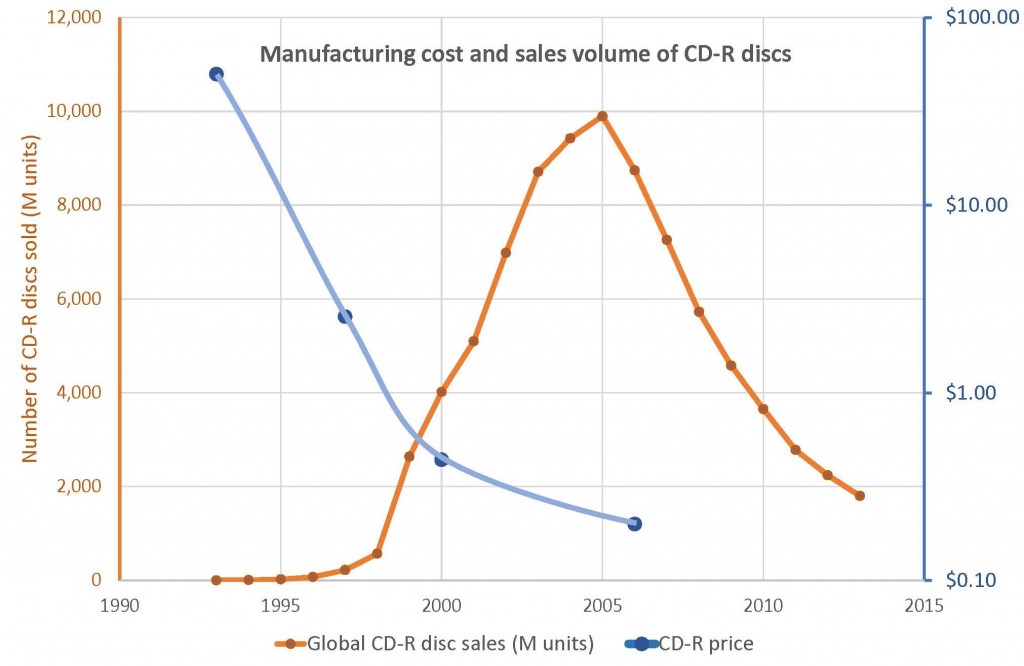

In a mature market the total market volume is no longer very sensitive to price. That is counter-intuitive because, in a mature market, manufacturers find it increasingly difficult to differentiate their products and they start to compete on price. Take, for example, recordable CDs (CD-R). This was a market of about 4 billion discs in 2010.

In a mature market the total market volume is no longer very sensitive to price. That is counter-intuitive because, in a mature market, manufacturers find it increasingly difficult to differentiate their products and they start to compete on price. Take, for example, recordable CDs (CD-R). This was a market of about 4 billion discs in 2010.

The price of CD-R discs declined from $50.00 in 1993 to $0.20 in 2006 (source: “report to the EU trade barriers regulation committee” page 13). Volume peaked around 2005 and the market is in steady decline today (source: TSR).

If one manufacturer manages to reduce the price of its product with $0.01, that product will certainly sell much better that the competitor’s CD-R disc. But suppose the average sales price of all CD?R discs decreases with $0.01, would that affect the total sales of CD-R discs?

The expiry of the CD-R patents provides an opportunity to study the effect of royalty payments on sales volume in a mature market.

CD-R’s essential patents expired in most countries between 2008 and 2009 and royalty payments stopped. At the time of expiration, manufacturers of CD-R discs typically paid between $0.025 and $0.035 royalties per disc. That is 15% – 20% of the sales price or 30% – 40% of manufacturing cost. The graph clearly shows that the reduction in royalty payments in 2008-2009 had no measurable effect on total sales volume. The curve shows a smooth, steady, decline.

In this mature market, cumulative royalty rates up to 40% of the manufacturing cost had no effect on the use of the standard. That makes these rates compatible with the purpose of the promise given by the companies that developed the standard to license their essential patents on RAND terms.

Are RAND terms a contractual obligation or necessary to avoid an anti-trust liability?

Even if a cumulative royalty rate of 40% of the manufacturing cost would be considered compatible with the SDOs contractual obligation to license on RAND terms, it may still be considered unreasonable from an anti-trust point of view. Is it misuse of a dominant position when a patent pool, licensing all essential patents, charges a cumulative rate that is 40% of the Bill of Material?

The answer ought to depend on the circumstances, as usual with anti-trust arguments.

It will depend on the availability of alternative technologies. With Wi-Fi, for example, companies that make mobile phones cannot avoid to integrate Wi-Fi in their product. With a standard such as Blu-ray Disc, movie publishers have viable alternatives such as DVD and streaming over Internet.

It may also depend on how the standard became dominant. Some standards are the sole survivor of intense competition between competing standards. VHS, for example, won the 3-way competition between VHS, Betamax, and V2000. The more recent battle between Blu-ray Disc and HD-DVD is another example.

In any case, some forms of licensing are more likely to invite anti-trust scrutiny than other forms.

A claim of misuse of a dominant position may be provoked, for example, when a patent owner does not publicly announce the intent to collect royalties until after manufacturers have launched products and then demand royalty payments that, if the manufacturer had known the rate before, would have prevented him from entering the market. This may come across as a ‘hold-up’ when it is financially impossible to stop selling the products and royalty payments must be made to avoid severe losses.

A patent pool with public rates, on the other hand, providing a one-stop shop for all essential patents, should provide a more comfortable position for the patent owners, certainly when the rates and other terms are accepted by at least part of the industry.

Licensing non-essential patents

There is usually more than one way to implement a standard. Good standards allow freedom of design and manufacturers will use that freedom to design products that are cheaper, faster, smaller, more efficient, or different in other ways that matter for their target market.

When manufacturers file patents on techniques that differentiate their implementation of the standard, these patents need not be licensed under RAND terms. They may be used exclusively to make their differentiation long term sustainable.

The distinction between essential and non-essential is, however, not always clear. When, for example, a patented technique enables a drastic cost reduction that makes all other implementations non-competitive, the use of that non-essential patent becomes unavoidable. Such a patent is sometimes called “commercially essential”.

Whether or not such commercially essential patents fall under the RAND license obligation depends on the exact wording of the IPR clause in the SDO’s bylaws. Sometimes they are included, other SDOs explicitly exclude them from the RAND commitment.

In any case, it can be argued that a refusal to license a commercially essential patent goes against the intent of the RAND licensing obligation, because it effectively blocks other companies from using the standard they have helped create. It could be risky for patent owners to rely on a strict interpretation of an SDOs IPR rules when arguing that a patent is not essential when there are no examples of products that implement the standard without infringing that particular patent.

Gaming the rules

A strict, literal, interpretation of the IPR clauses in an SDO’s bylaws provides opportunities for creative minds to find methods that circumvent the contractual RAND license obligations.

What if the company that signed a RAND license obligation sells its essential patents to another company? Does the obligation travel with the patents when sold, or is the new owner free to use the essential patents exclusively?

What if the patent owner does not itself participate in standards development, but contracts an independent company to participate and promote the use of its patented technology in the standard? Will the patent owner be free to use its essential patents exclusively and block others from using the standard?

SDOs will try to prevent circumvention of their IPR clauses by making their IPR clauses more sophisticated and considerably longer. That can help, but it would be naïve to expect that all loopholes can be plugged.

In practice, attempts to game the rules are rare. Most patent owners will consider it too risky to violate the original intent of the SDO’s rule that essential patents must be made available on RAND terms and conditions.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

One comment so far.

Tineke Egyedi

August 6, 2016 01:58 pmThis is a highly interesting piece, both because the author attempts to quantify the effect of royalty stacking for emerging and mature markets – albeit theoretically in the WiFi case; and for pointing out some phenomena (e.g. the relevance of taking in whether alternative technologies exist; of independent consultancy firms under FRAND).