Any views or opinions expressed by me in this article are solely my own and do not necessarily represent those of Oracle Corporation, its subsidiaries or affiliates.

_______________

Please stop filing extremely short, overly broad patent claims. This may seem like a simple request, one for which it is easy to say: “He’s not talking about me—my claims are reasonably short and broad, but not extremely short and overly broad.” If you are a patent attorney who prosecutes applications in the software-related arts, it’s safe to assume I am talking about you.

Over the past couple of years in my roles as Senior Patent Counsel at Oracle and as Adjunct Professor of Software Patents at Chicago-Kent College of Law, IIT[1], I have often found myself discussing extremely short and/or overly broad patent claims with patent attorneys and patent agents who draft patent applications. Whenever I suggested the claims were extremely short and/or overly broad, I received responses that were, to my surprise, mostly defensive of the strategy: “this claim would be a really valuable claim if we got it,” and “we might get it—I’m not aware of any prior art on point.” My initial response was “you’re wrong, fix it” with reference to several examples of prior art off the top of my head. That said, at that time, the discussion had become one of competing dogmas (checked by my knowledge of the prior art) rather than one of science.

I am not the first person to make the observation that extremely short independent claims can serve as one good indication . For example, the U.S. Patent Office (USPTO) has recognized that overly broad patents are an issue and has taken steps to address it. The USPTO created a Sensitive Application Warning System (“SAWS”) to provide additional review for improving patent quality. As described on the USPTO web site and in response to a FOIA request, SAWS was designed to provide additional pre-issuance review of, for example, “applications with claims of broad or domineering scope” and “applications with claims of pioneering scope.”[2] The SAWS program received some criticism for being kept secret, and because there were no apparent rules to guide its potentially broad but practically narrow application.[3] The program was retired in 2015.[4]

The USPTO examiners and patent practitioners have also loosely and less formally used a “One-Hand Rule” to gauge extremely short and overly broad independent claims.[5] The one-hand rule is used by some to determine that a claim is unlikely to contain allowable subject matter if it is not longer than the reader’s hand. As will be explained in more detail below, it turns out that the One-Hand Rule (or a more precise variation of it) is a good way to identify low quality patent applications (i.e., applications that are not expected to efficiently proceed towards allowance).

The clear need to improve patent quality has been well documented in both mainstream media and technical and legal sources.[6] The discussion for improving patent quality needs to proceed scientifically, driven by an empirical analysis of data, to avoid the pitfalls of competing dogmas. I recently conducted a study to measure the effectiveness of various prosecution strategies. The study covered over a hundred thousand patent assets pursued by software companies, and for this sample, I found that filing extremely short, overly broad patent claims is a bad strategy in just about every way imaginable.

My study addressed the following questions:

- How short is extremely short?

- How prevalent is the strategy of pursuing extremely short, overly broad claims?

- Are people really getting these claims?

- If so, are some firms/companies better than others at getting these claims?

- If not, how much time and money is being wasted on this strategy?

- What are the other measurable costs of this strategy?

I found that:

- Cases with independent claims of less than 300 characters (or approximately 60-75 words, 4 full lines of text, or less than half the length of an abstract, which is capped at 150 words) had dramatically different prosecution lives than cases with independent claims that were all longer than 300 characters.

- At one extreme, a major software company used this strategy in as many as 13% of their cases as filed. Other software companies used the strategy significantly less frequently.

- Consistently, roughly 0% of the issued patents had extremely short independent claims.

- Nobody seems to be better than anyone else at getting these claims.

- On average, the strategy costs 2-3 more office actions and 1 extra RCE (roughly $10,000).

- This strategy leads to longer (presumably narrower) claims as issued for claims near the threshold of 300 characters, and the strategy also leads to more prosecution history estoppel.

The study and its findings are explained in more detail below and were also detailed in a recent Topic Submission for the USPTO Quality Case Studies.

Through their outside patent counsel, companies pursue extremely short claims to a variable extent, yet to their consistent detriment. The study investigated characteristics of the patent portfolios of four large companies with a wide range of software-related products and services. The identities of these four companies (“Companies A-D”) are being kept confidential. For each of companies A, B, and C, all published U.S. applications and patents were included covering the lifetime of each respective company, as of the beginning of 2016. For Company D, published U.S. applications and patents were included with filing dates ranging over a fixed period of 6 years during an exploratory phase of the study. This article focuses on results from two of the companies, Company A and Company B, that have pursued extremely short claims to varying degrees. The results for Company C fell between the results for Companies A and B. Company D rarely pursued extremely short independent claims.[7]

Companies pursued extremely short independent claims[8] in 3-13% of their cases, but these claims were present in roughly 0% of their issued patents. In other words, nobody is getting these extremely short independent claims through the patent office. For highly developed technologies such as computer software and hardware, it is extremely unlikely for the USPTO to issue a patent with extremely short independent claims. The English language might just require more space to adequately define the scope of these highly developed technologies.

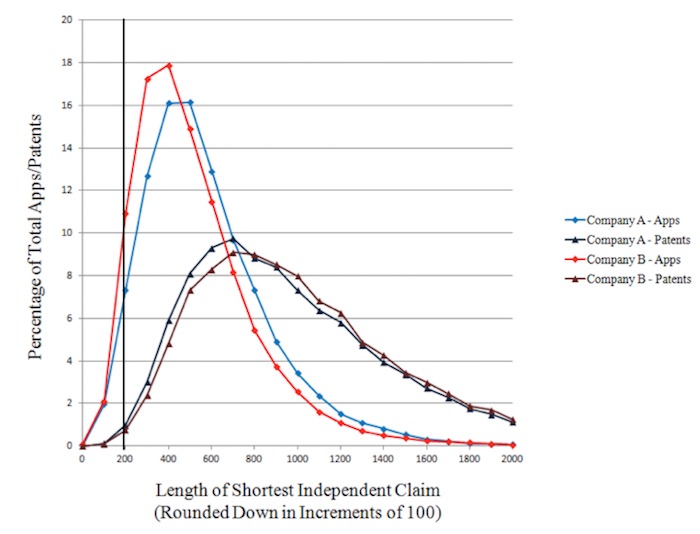

The study focused on finding cases that statistically have almost no chance of allowance in their condition as filed. I found that extremely short independent claims were present in 1% or fewer of issued patents even though originally-filed applications had these extremely short claims much more frequently.[9] I also found that companies differed in how aggressively they pursued these extremely short claims. For example, Company A pursued the extremely short claims in 13% of their applications as filed, and Company B pursued the extremely short claims in 9% of their applications as filed. Despite the variable inputs (13% and 9%, respectively) to the patent office, the output was roughly the same: these extremely short independent claims were present in 1% or fewer of issued patents for both of these companies. In fact, Company B obtained a slightly higher percentage of patents with extremely short independent claims despite the lower frequency with which they were initially pursued. In other words, pursuing these extremely short claims almost never results in an issued patent, but some companies still aggressively pursue them.

Chart 1 below shows the percentage of applications filed and percentage of patents granted for Company A and Company B, respectively, based on the length of the shortest independent claim (rounded down in increments of 100). About 9% of cases filed by Company A had an extremely short independent claim. About 13% of cases filed by Company B had an extremely short independent claim. For both companies, 1% or fewer patents had an extremely short independent claim.

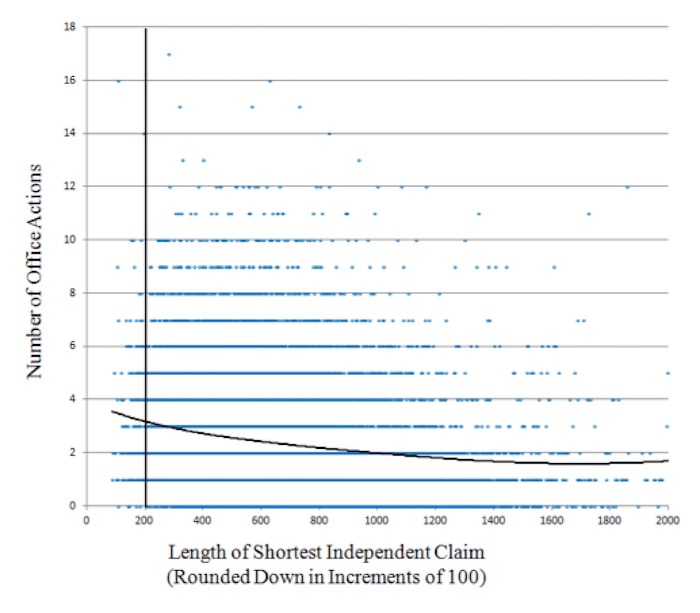

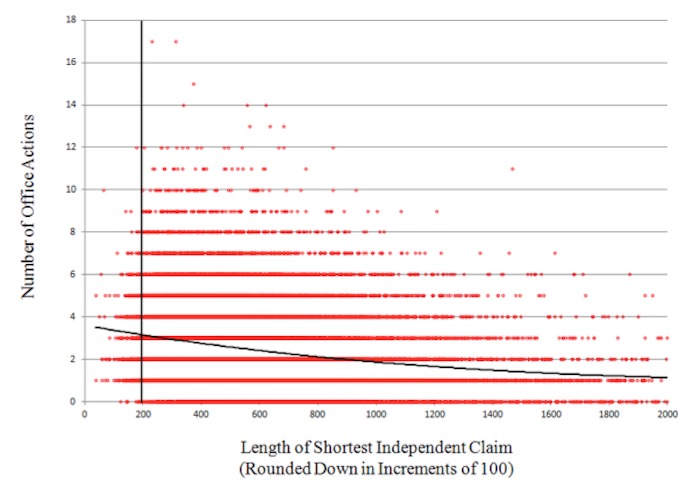

Avoiding the strategy of pursuing extremely short claims could result in significant savings for an applicant (your client) in terms of direct prosecution costs and prosecution history estoppel. The study concluded that, on average, the strategy of pursuing extremely short overly broad claims costs 2-3 more office actions and 1 extra RCE, as well as increased prosecution history estoppel and possibly even narrower claims. This is particularly clear when looking at the independent but similar-looking datasets from Companies A and B.[10] The estimated 2-3 additional office actions cost applicants approximately $6000-$9000 in attorneys’ fees alone.[11] Given the cost of a second RCE at $1700, the total cost of this ineffective approach is roughly $10,000 per case. The study also concluded that the expense was not well spent. For applications with independent claims near the threshold length of 300 characters, those with fewer than 300 characters actually ended up with longer claims as issued than those with more than 300 characters.[12]

Charts 2-3 below show the number of Office Actions received by Companies A and B, respectively, based on varying starting claim lengths.[13] Applications starting with longer, but not extremely long, independent claims (1600-2000 characters, or about 2.5 to 3 times the length of an abstract) on average have 2-3 fewer office actions than applications with extremely short claims. The trend lines are shown in black with a polynomial fit order n=6.

As would be expected, the number of RCEs filed in each case roughly tracks the number of Office Actions, as shown in Charts 2-3, with a delta of about one fewer RCE between the strategy of pursuing extremely short claims and the strategy of pursuing longer (but not extremely long) claims.[14]

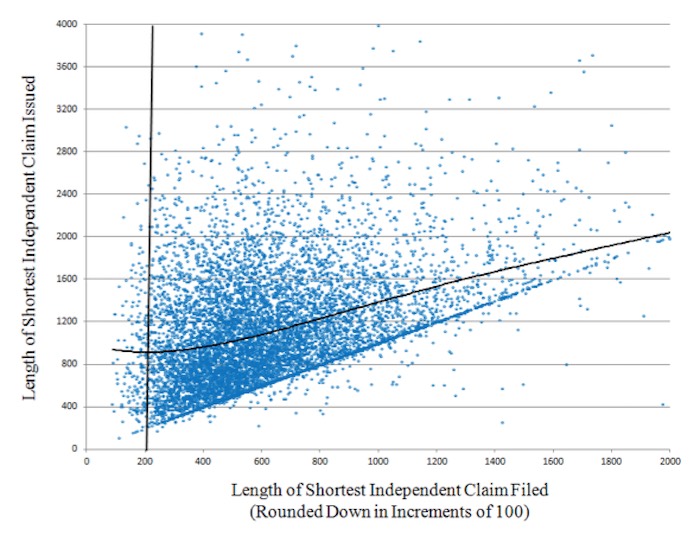

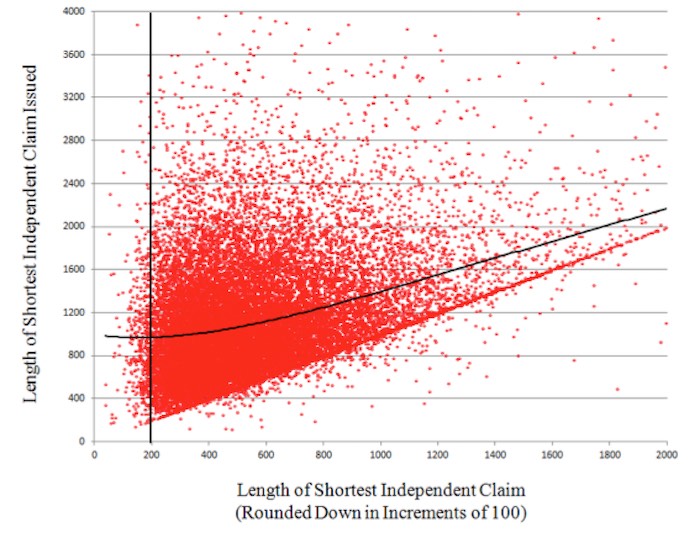

Charts 4-5 below show claim lengths issued to Companies A and B, respectively, based on varying starting claim lengths. The local minimum at about 300 characters indicates that claims starting with less than 300 characters are likely to end up longer as issued than claims starting at or slightly above 300 characters. If taken as a percentage of prosecution history estoppel added to the claim as filed, claims below 300 characters are changing in length by more than 200%.

I am not suggesting that longer claims are “better.” If the applicant’s goal is breadth, and if claim length is a proxy for breadth, then shorter claims are better to the extent that they define the metes and bounds of new and non-obvious technology. For independent claims less than 300 characters in length, there is generally not enough content to define the metes and bounds of new and non-obvious technology, as evidenced by the roughly 0% of issued patents having these extremely short independent claims. What I am suggesting is that that a strategy with a 0% likelihood of success is a bad strategy.

I would supplement these empirical findings with my own experience (as a result of attending roughly 100 disclosure meetings a year) that extremely short claims are a good indication of laziness at the disclosure meeting and application drafting stage. A disclosure meeting can last as long as 2-3 hours where the attorney(s) and inventor(s) ultimately understand and reach an agreement on what is new and non-obvious about the technology in light of a wide range of prior art; or, a disclosure meeting can last as little as 15 minutes where the attorney(s) and inventor(s) may understand the field of the invention but end the meeting before the real discussion begins. As shown by this study, the field of the invention turns out to be a bad starting point for patent claims—in other words, laziness is bad, and I am calling you out on it.

For the sake of applicants, I hope all patent attorneys carefully consider the implications of this empirical evidence before pursuing an extremely short, overly broad independent patent claim. In-house counsel and non-attorney clients should carefully consider the impact of this strategy on their patent budget. For a company that files 1,000 cases per year and pursues this strategy in 10% of their cases, the strategy could be costing the company $1,000,000 per year. Outside counsel also need to recognize that, with respect to impressing clients, actions speak louder than words. Any patent attorney can draft a broad claim, but it takes hard work and skill to carefully consider and craft a claim that is expected to:

- provide the needed scope of protection,

- efficiently survive patent examination by the USPTO, and

- survive additional review by the Patent Trial & Appeal Board (PTAB) and courts.[15]

Sincerely,

Eric L. Sutton

________________

[1] Chicago-Kent College of Law, Illinois Institute of Technology, has the highest-ranked intellectual property program in the Midwest according to U.S. News & World Report (March 2016).

[2] Gaudry, Kate S. “Re: Freedom of Information Act Request No. F-15-00004.” 9 Oct. 2014. Made available by AlyssaBereznak. “SAWS FOIA Response.” Scribd. Web. 10 May 2016.

[3] Gaudry, Kate S. “Secret PTO Program Subjects Apps To Heightened Scrutiny.” Law360. 3 December 2014. Web. 10 May 2016.

[4] USPTO. “Sensitive Application Warning System.” 2 Mar. 2015. Web. 10 May 2016.

[5] just_n_examiner. “The One-Hand Rule.” LiveJournal. 20 Jul. 2005 Web. 10 May 2016. Stein, David. “The New Practitioner/Examiner Relationship: Collaboration For Valid Patents.” USPTO Talk. 8 Feb. 2015. Web. 14 May 2016. Philip G. Emma, “Five strategies for overcoming obviousness”, IEEE Micro, vol.26, no. 6, pp. 72, 70-71, Nov./Dec. 2006, doi:10.1109/MM.2006.110.

[6] “When Patents Attack!” This American Life: Episode 441. 22 July 2011. Web. 9 May 2016. Goble, Gord. “10 tech patents that should have been rejected.” PCWorld. 21 May 2013. Web. 14 May 2016. See El-Gamal, Yasser M., LaPorte, Lawrence R., Mikulka, Yuri. “Down the Rabbit Hole: Trends in Software Patent Court Decisions Post-Alice.” Lexology. 22 Dec. 2015. Web. 9 May 2016.

[7] Extremely short independent claims appeared in less than 3% of Company D’s applications and in about 0.2% of Company D’s patents.

[8] Defined as less than 300 characters, or approximately 60-75 words, 4 full lines of text, or less than half the length of an abstract, as summarized in the findings of the study.

[9] The data for my study was gathered using claims exported from Innography® for applications filed and for applications issued within each company’s corporate tree, using data from applications as published to measure applications as filed. I then automatically and uniformly determined which claims were independent claims and automatically and uniformly determined the length of the independent claims for each case. I combined this information about the length of independent claims with information from LexisNexis PatentAdvisor® about the number of office actions and RCEs for each case. I would like to thank Addam Kaufman and Tonya Yan for their hard work and contributions to my various patent quality studies over the past two years.

[10] See Charts 2-3.

[11] Gaudry, Kate S. “How USPTO Teleworking Program Impacts Patent Applicants.” Law360. 12 May 2014. Web. 9 May 2016. (noting on page 3 the average attorney fees of $3000 for an office action response); Report of the Economic Survey 2015. AIPLA. Prepared under direction of the AIPLA Law Practice Management Committee by Association Research, Inc. June 2015.

[12] See Charts 4-5.

[13] Charts 2-5 were capped at initial claim lengths of 2000 characters and, for charts 4-5, issued claim lengths of 4000 characters. The caps were introduced to increase the visibility of the 200-299 character marker.

[14] The RCE charts were excluded as redundant.

[15] See El-Gamal, Yasser M., LaPorte, Lawrence R., Mikulka, Yuri. “Down the Rabbit Hole: Trends in Software Patent Court Decisions Post-Alice.” Lexology. 22 Dec. 2015. Web. 9 May 2016.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

29 comments so far.

Jeff Lindsay

August 4, 2016 05:11 amAnon @28, great comments on preparing to protect trade secrets. So few companies understand that.

Anon

May 21, 2016 09:48 amNight Writer @ 25,

Let me play the Devil’s Advocate for a moment and treat the trends as they are (without remorse for what is clearly a series of bad decisions for promoting the progress) for the topic of advising clients (in general – this should not be taken to be legal advice by any individual reader) on the “path forward into darkness.”

Going “dark” does not mean “going blind.” Those pursuing trade secrets need to realize how fragile these things may be and plan accordingly – and counter-intuitively, may need to spend more money. Do NOT neglect the writing down and development activities that come from the patent process (and to which much additional value beyond the inventor’s first “A-Ha” moment derive). Often lay people may confuse what a good patent attorney does in fleshing out an invention as inventive work itself – but what a good patent attorney actually does is merely take that first “A-Ha” and see what is already there “in the block of marble,” and carve out much more than just that first “A-Ha.” This is not further invention as much as it is making sure to capture the full scope of the real first invention.

If people think that going dark means that they do not have to spend the money and time (which is money) on this value added activity, they will simply be spending less money and time (which is money) to obtain something of far less value. One must maintain a value-to-value view when looking at costs.

Additionally, the AIA does provide a (new, or at least greatly newly expanded) benefit called the Prior User Right (it is actually not a “Right” in the sense of a patent right, but more of a submarine attack against anyone else that may obtain an actual patent right). While this area of law (as derived from any adjudicated conflicts) remains sparse, it remains clear that to obtain any benefit under this regime, one will need to have documentation – and proper documentation as to timing and content – which can flow from the same maintained internal invention development mechanisms that support patent filing. One can “go dark” and not engage the patent process (with its inherent publications), but one should not “go blind” and not engage the documentation (and development) process altogether.

Anon

May 21, 2016 09:32 amMr. Beem,

Long enough to reach the ground – well stated (and much better than the unthinking use “x” number of words).

Richard Beem

May 19, 2016 11:17 pmMy reply: How long should a patent claim be? http://www.beemonpatents.com/2016/05/how-long-should-a-patent-claim-be/

Night Writer

May 19, 2016 01:41 pm@24: Ternary –I’d have to look at the applications. But, probably if the attorney is dealing with inventions in nearly the same area and been working for a couple of years in the area, then your numbers seem reasonable. Probably have to be an in-house attorney to avoid the overhead of the law firm.

I understand what you mean about the return in value. Patents have been decimated with the AIA and hostility towards patents from the judiciary.

My guess-with the new trade secret act is that some big companies may go dark. They will just fight endlessly anyone that sues them at the PTO. And, maybe file some patents on tech that they can’t help but make public. The whole game is going to turn into the game that was played in the 1980’s of locking people down and keeping everything a secret. I still find it incredible that the patent system created the best software industry in the world by far (and other countries that didn’t have patents now have nothing). Now–suddenly–the patent system is destroying everything (somehow) and we must get rid of it.

Ternary

May 19, 2016 11:49 amNight @14

We figured out that for about $ 6k per application a team of one experienced attorney and two patent engineers can do about 80-100 applications of high quality a year. This allows everyone to spend enough time on an application to dig into the technology, read prior art and follow important court cases and blogs and enjoy drafting applications without degrading to a patent mill that cranks out cases.

No doubt that you need quality people that you all pay a decent but not exceptional salary and you cannot do this with entry level engineers without the required skills, experience and knowledge.

Well, that is not entirely true. You can of course hire inexperienced lowly paid engineers who crank out specs, and attorneys who slap on some claims based on what they understand from a 15 minutes briefing on what the invention is. But that is not what I am suggesting.

Many businesses are constantly strapped for cash and are looking where to cut money, especially if no value is added. Be it with short or long claims. Right now, I very reluctantly and with great regret have to say, that the patent system seems to offer low value for high cost. Perhaps a very good question for a CEO in Gene’s upcoming seminar is, “how much money, if any, should I spend on patents in this environment?” https://ipwatchdog.com/2016/05/16/executives-need-to-know-about-patents/id=68855/

A Rational Person

May 19, 2016 06:59 amInterestingly, with respect to method claims, I learned a different version of the “one-hand rule”: a method claim that is longer than your hand is effectively unenforceable because it will include an unnecessary step or limitation that can be easily avoided by potential infringers.

For example, with respect to a chemical synthesis of a new compond, the ideal claim is often to claim the last step in the synthesis, i.e., the step where you go from the last intermediate to the new compound. Every step you add to the claim that takes place prior to the last step is a chance for a potential infringer to use an alternative method to get to the last intermediate compound.

Night Writer

May 19, 2016 12:09 am@20 Curious. I agree. Adding the limitations you need to overcome the prior art is the way to go. A lot of these big claims have lots of nonsense in them.

KenF

May 18, 2016 11:53 pmwrite your claims just right

protect the invention so

PTO no work

Look, claim haiku!

Curious

May 18, 2016 11:46 pmA few random thoughts:

Companies pursued extremely short independent claims[8] in 3-13% of their cases.

A lot of verbiage spilled over such a small set of applications.

If you start with a very short (but perhaps not “extremely short” claim), you can add only those limitations necessarily to overcome the prior art. Moreover, if you use your dependent claims wisely, those limitations can be found therein. However, what I have found with “long-ish” claims (either that way from the beginning or after prosecution has taken its toll) is that attorneys are rather reluctant to take out unneeded claim language.

I have handled more than my fair share of transferred applications. I frequently observe claim limitations that were added to overcome prior art merely result in an additional reference being tacked on in an obviousness rejection, and that obviousness rejection not being traversed. Instead, the attorney takes a different tact. However, instead of removing this added language (in taking the different tact), the attorney leaves it in. If the language isn’t helping you overcome the prior art, then get rid of it. Far too often that language is not removed.

The problem with avoiding “extremely short claims” is that it tends one to overshoot the target and craft claims that are a bit too wordy than necessary. It is easier to add limitations (because those limitations being added are directed to the prior art you are looking at) versus removing limitations (because you don’t know what other prior art the Examiner might then be able to drag in).

If there is a “Goldilocks zone” for number of characters/words for patent claims, it is easier to find it by adding claim limitations than subtracting claim limitations. This isn’t to say one should make the shortest possible claim the end goal. However, with a good independent claim, one should be able to easily identify the “inventive concept” because the only other limitations present are those needed to put the “inventive concept” into context. Well written dependent claims should be able to get you into the Goldilocks zone if you’ve exercised too much brevity in drafting the independent claim.

Peter Kramer

May 18, 2016 11:17 pmConsider the claim that was allowed for the ball point pen, which claimed,

“a spheroidal marking point, substantially as described.”

Anon

May 18, 2016 08:20 pmWell played, step back, well played.

step back

May 18, 2016 05:52 pmLOL

(3 chars)

step back

May 18, 2016 05:51 pmAh brevity.

(11 characters 😉 )

Anon

May 18, 2016 04:50 pmLength – or shortness – sometimes has an inverse relationship with time crafting the item.

(76 characters – 😉 )

Night Writer

May 18, 2016 02:36 pm>>One efficient way is to require from outside counsel to change their billing structure and demand that lower rate patent engineers/technical advisors are involved. Or hire inside patent engineers to draft higher quality invention disclosures.

I get applications transferred into me that were written like this. The in-house attorneys give us a constant stream of these. They invariably have some serious problems. I don’t say that non-attorneys cannot be trained to write great applications, but the reality is that much of our training enables us to focus in on what is important and add a lot of value to the application. Maybe the way to increase quality is to increase the budget for the application.

I always see these clients that want to save $2-$5K per application by forcing us to take less. I often think, well you are only writing like 100 a year. So, you are going to put a big squeeze on us for $200k a year. What you are doing is forcing us to either make less money or spend less time on your application.

I think the hyper focus on how low they can get us to write applications is what has contributed so much to quality issues.

KenF

May 18, 2016 02:24 pmMy offering comes in at 81….

Kate

May 18, 2016 01:07 pmFair points are being made as to whether short claims should be filed.

However, the article is focusing on whether EXTREMELY short claims (not just short claims) should be filed. Extremely short claims are defined as those 300 characters or less. How short is that? This paragraph is exactly 300 characters. Imagine a claim including fewer characters than this paragraph.

Thought that it might be helpful to provide the visual as to how short <300 characters really is. In my view, it would take a rather exceptional invention to be able to claim it with such brevity in a manner that stood up to 102 and 103 (or 112(2)).

KenF

May 18, 2016 11:50 amIt ALL depends on the particular situation. One of my all-time favorite claims is this: 1. White balsamic flavor vinegar comprising a blend of concentrated white must and white wine vinegar. From U.S. 5,565,233. There is nothing per se wrong with a short claim, so long as it is properly supported and the prior art merits it, and it is not over-reaching in view of section 112 (i.e., trying to claim more than is enabled, reasonably disclosed, etc.).

Anon

May 18, 2016 11:26 amI would add to my previous comments that the typical approach of a family of dependent claims should already be “typical,” and would capture the sage advice offered by “Concerned.”

That being said, to leave off the table the “upper ranges” may not be the most sage advice (and reflects more than a bit of “hindsight” “buyer’s remorse.”

I would also add that a frank discussion with the client about claim strategy should already be covering these topics (and to that end, any such “hindsight” concern is thoroughly proper in a forward-moving environment). As would be a general discussion on the opposite trends of patent protection and trade secret protection (as much as I believe in the value of the patent system for the betterment of all parties, and the relative detriment of following the path of trade secrets, the client needs to be informed of the state of the law and the client gets to make that (informed) choice.

Paul F. Morgan

May 18, 2016 11:22 amEnjoyed reading this article, plus some good comments. It seems that there are some things that never change and have to be relearned by each new generation of claim scriveners.

The increased willingness of clients to file low cost “shots in the dark” patent applications – filings with no prior art searches – is [as demonstrated here] “penny wise and pound foolish.” It has certainly contributed to the problem. The specifications thereby may even lack valid support for adding distinctions over the prior art to the broad “shot in the dark” claims.

Ankylus

May 18, 2016 10:55 amThis passage caught my eye:

“Whenever I suggested the claims were extremely short and/or overly broad, I received responses that were, to my surprise, mostly defensive of the strategy: ‘this claim would be a really valuable claim if we got it,’ and ‘we might get it—I’m not aware of any prior art on point.’ My initial response was ‘you’re wrong, fix it’ with reference to several examples of prior art off the top of my head. That said, at that time, the discussion had become one of competing dogmas (checked by my knowledge of the prior art) rather than one of science.”

I do hope your interactions with outside counsel are somewhat more than this. If not, “and I am calling you out on it”, the fault is yours. If you know of “several examples of prior art off the top of my head” that your outside counsel doesn’t know, that’s on you for not communicating it to him before he sets out. Or if you communicated it to him without indicating its significance, that is on you too. You are setting him up for failure. Also, the process is supposed to be collaborative. You might actually point out where the claim is too broad.

I don’t know if it is arrogance or incompetence, but the tone of the article suggests arrogance. Really, if you want to school people using empirical evidence, pop over to Patently-O. Professor Crouch is very good at that kind of thing.

Also, what happens in cases where you have both “extremely short” and “overly broad” claims and claims that meet your empirical standards?

Ternary

May 18, 2016 10:35 amAll outside attorneys have to make their billable hours. Not many can refuse to do an application for let’s say $ 7000, especially when offered a bunch of them. At $300/hour the attorney cannot even spend 25 hours on the application. Many will still say that 25 hours is mooooore than enough. Experienced claim writers are able to crank out beautiful short and broad claims.

We often discussed this in our offices and we came to the conclusion-like Eric Sutton, in this well researched article- that nowadays submitting these claims is like waving a red flag. And also creates many of the current post-issuance problems. We decided to apply a patent engineering model that teams a patent engineer (billed at significantly lower rates) with the inventor to “engineer” the specification and claims. This allows us to spend up to 45 hours on a case for the same amount of money and provide a much higher technical, structural and detail quality of the application. This puts the attorney in a role of a reviewer/editor with fewer billable hours and has to make it up with more cases and/or the profits on the engineer.

“The estimated 2-3 additional office actions cost applicants approximately $6000-$9000 in attorneys’ fees alone.” Right there is the incentive for writing short claims. It still provides outside counsel the opportunity to bill in total $ 16,000 for a case.

If clients are truly interested in quality they should start demanding quality. One efficient way is to require from outside counsel to change their billing structure and demand that lower rate patent engineers/technical advisors are involved. Or hire inside patent engineers to draft higher quality invention disclosures.

Concerned

May 18, 2016 07:59 amI think this is great advice to those who write claims for a living. From my perspective short claims that are overly broad are like a dual edge sword. On one hand, a broad patent may attempt to cover a large set of products. On the other hand, the short claim is much more likely to have prior art just waiting to be uncovered by those with an incentive to do so. So sure, admire your short claim after you fight through multiple rejections and RCE’s, but your admiration may turn to remorse if you attempt to enforce your short claim overly broad patent.

IMHO adding appropriate limitations to claims, and thus making it less broad, is sound advice for either a software or hardware oriented patent. And adding appropriate limitations to (software) claims adds structure and may make it less likely to be viewed as an abstract idea and subject to being invalidated in the wake of the Alice decision.

To be sure, there are exceptions where short broad claims are appropriate such as when an invention is truly novel. So let us not misunderstand the point of this blog. And thanks to Eric Sutton for making a contribution pointed in the direction of improving patent quality.

Anon

May 18, 2016 06:38 amSilk purses from sow’s ears, and all that.

I do hope the author remembers that it is the client that is ultimately in charge of what is filed. Yes, we can have our standards and yes we can refuse to represent clients (at least some of us and at least theoretically), but (often) it is the client’s call on a number of factors involved with “the call” for better quality from the practitioner’s end.

I place this article in the “sound’s good and noble albeit a bit pollyanna” category (which makes it a bit disappointing after reading the credentials of the author). Absolutely nothing wrong in principle with wanting a more robust end product, but a bit over the top on wanting some blanket “claim must be “X” long” type of rote rule.

Daryl

May 18, 2016 03:28 amEric, while reporting statistics, considers sufficiency and practicality rather than drafting ‘rules’. As practitioners, we address client goals with strategy suitable to the purpose and effective patent/product/market cycles. Drafting claims that tend to draw rejections risking estoppel, overly relying on reference to the spec & drawings (which risk estoppel) and/or drafting/prosecuting to “make it thru the patent office” (rather than also considering potential licensing, litigation, 3rd party challenges, etc.) are risky in my years practicing, as mentor, team leader, clerk &/or counsel – and especially as ‘fixer’. Perhaps jmore important to the examiner, Judge, jury, licensee, etc. than the word count of a particular claim is the story told by the spec, claim groupings, portfolio, positions espoused elsewhere and hopefully sufficiently capable counsel. (It also doesn’t hurt to consider the roles of the various participants and to allow or even support opposing parties in hanging themselves.) However, the statistics Eric reports and his observations do provide some insight &, perhaps just as importantly, invite necessary debate.

Saws (also referred to as the PTO’s secret police or the ‘them’ excuse) is/was a different matter altogether. Please don’t get me started.

Night Writer

May 17, 2016 07:49 pm@2 also from personal experience long claims are a pain in litigation. You get these giant phrases that a layperson isn’t ever going to understand–not ever.

step back

May 17, 2016 07:09 pmWriting long claims is easy. (Just as saying something with more words is easy.)

Polishing it down to the bare essentials is the hard part.

Also recall that claim terms are construed in light of the specification (even when BRI is involved). So it can’t be just the number of words in the claim as viewed in a vacuum.

Night Writer

May 17, 2016 05:45 pmWhat if the people that write short claims are also the ones that fight harder for the claims so they end up with more OAs?