Biopharmaceutical innovation is difficult, expensive, time-consuming, and risky. More so now than ever. A 2014 study by Tufts University’s Center for the Study of Drug Development calculated that a mere one in eight (11.8%) of all drugs that enter clinical trials are ultimately approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The drug development gamble appears to be getting riskier. A report released on May 25th by the Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO), the biotechnology industry’s national trade group, finds that fewer than one in ten (9.6%) of drugs that enter clinical trials will gain approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Biopharmaceutical innovation is difficult, expensive, time-consuming, and risky. More so now than ever. A 2014 study by Tufts University’s Center for the Study of Drug Development calculated that a mere one in eight (11.8%) of all drugs that enter clinical trials are ultimately approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The drug development gamble appears to be getting riskier. A report released on May 25th by the Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO), the biotechnology industry’s national trade group, finds that fewer than one in ten (9.6%) of drugs that enter clinical trials will gain approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

The BIO study provides the most comprehensive analysis, to date, of clinical trials in the biopharmaceutical industry, analyzing 9,985 clinical and regulatory phase transitions[1] across 1,103 companies. Focusing on research and development (R&D) success between 2006 and 2015, the study calculates the Likelihood of Approval (LOA) from Phase I.[2] Figure 1, below, captures the success rates across all clinical trials.

![Figure 1: Phase Transition Success Rates and Likelihood of Approval (LOA) from Phase I for All Diseases, All Modalities[3]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/lybecker-f1-06-2016.jpg)

Figure 1: Phase Transition Success Rates and Likelihood of Approval (LOA) from Phase I for All Diseases, All Modalities[3]

Success rates in Phase II are by far the lowest (30.7%), followed by Phase III (58.1%). This is the point at which costs increase and decisions must be made about whether or not to terminate the project. BIO reports that 35% of all R&D spending is now spent on Phase III development, and Phase III trials account for 60% of total clinical trial costs. Not surprisingly, Phase III clinical trials are the longest and most costly.

Importantly, success varies greatly across disease areas. The BIO study examines R&D success by disease area. Figure 2, below, depicts their findings. Considering the 14 disease areas analyzed, Hematology shows the highest Likelihood of Approval from Phase I at 26.1%, while Oncology drugs had the lowest at 5.1%. Notably, high prevalence chronic diseases had a lower LOA from Phase I at 8.7%, relative to the overall dataset (9.6%). At the other extreme, (non-oncology) rare diseases enjoy a LOA from Phase I of 25.3%, a rate that is 2.6 times that of the LOA for all diseases, and three times greater than that of chronic diseases with high populations.

Clearly, the scientific challenges of biopharmaceutical research are immense and admittedly contribute to these low success rates. As described in the BIO study:

Greater flexibility with alternative and novel surrogate endpoints, the utilization of adaptive clinical trial design, improved methodologies for assessing patient benefit-risk, and improvements in communication between sponsors and regulators could help improve the success rates reported in this study. Simultaneously, improvements in basic science can enable better success rates. For example, more predictive animal models, earlier toxicology evaluation, biomarker identification and new targeted delivery technologies may increase future success in the clinic.[5],[6]

Less obvious is the role of uncertainty in intellectual property rights in decisions to terminate research programs. Specifically, the study notes, “[c]ompetition, IP litigation, and other market factors could result in the termination of a program.”[7] As described in my earlier contribution, intellectual property rights protections enable innovators to recover the tremendous investments of time and money, which are necessary for biopharmaceutical R&D. Without IP protection, the low probability of success – probabilities that the BIO study shows are falling – makes it difficult to justify spending the resources needed to develop new treatments and therapies.

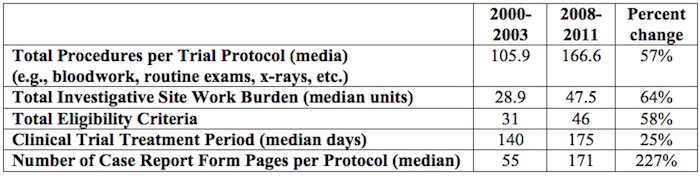

IP protections are even more important given that the number and complexity of clinical trials required by the approval process have multiplied considerably, as shown in Table 1, below.

Moreover, as the costs of clinical trials rise, these costs are increasingly born by the biopharmaceutical industry. The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health reports that the biopharmaceutical drug and medical device industry now funds six times more clinical trials than the federal government.[10]

Fundamentally, biopharmaceutical research is increasingly difficult, risky and expensive. As such, strengthening the intellectual property protections that incentivize these innovations is essential, including safeguarding the data generated by clinical trials through data exclusivity protections. Without a rigorous, effective IP regime, the incentives to invest in the risky, expensive, time-consuming drug development process erode.

The BIO report is a call to action. Biopharmaceutical IP must be protected, at home and abroad.

As President Obama continues to push the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) Agreement, the statistics on R&D success are reminded that the Agreement must strike a balance between incentivizing innovation and ensuring access to medicines. Acknowledging that shortened periods of data exclusivity protection improve access to competing biosimilar drugs, greater access won’t mean much if innovation is stymied and new drug development stalls. Given the importance of intellectual property rights to economic growth and technological development, the as well as the wider benefits of biopharmaceutical research, we must ensure that biopharmaceutical research continues – and that requires strong IP protections.

[Kristina]

________________

[1] The BIO study defines a phase transition as “the movement out of clinical phase – for example, advancing from Phase I to Phase II development, or being suspended after completion of Phase I development”.

[2] As described in the BIO study, the “LOA success rate is simply a multiplication of all four Phase success rates, a compound probability calculation. For example, if each phase had a 50% chance of success, then the LOA from Phase I would be 0.5*0.5*0.5*0.5 = 6.25%”.

[3] Source: Thomas, David W., et al., “Clinical Development Success Rates 2006-2015,” Biotechnology Innovation Organization, June 2016, p.7.

[4] Source: Thomas, David W., et al., “Clinical Development Success Rates 2006-2015,” Biotechnology Innovation Organization, June 2016, p.8.

[5] Please consider the definition of surrogate endpoints from my earlier IPWatchDog piece: Fundamentally, surrogate endpoints are outcome measures that reflect important milestones, though they are not of direct practical importance. Consider the following examples: measures of cholesterol may be used in clinical trials where cholesterol reduction is used as a proxy (surrogate endpoint) for reduced mortality; blood pressure is frequently used as an outcome in clinical trials since it is a risk factor for stroke and heart attacks. Physiological or biochemical markers are frequently used as surrogate endpoints since they are quickly and easily measured and are assumed to predict important clinical outcomes. (www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/bandolier/booth/glossary/surrog.html ) According to the Williams et al. study, “A major factor determining the duration of a clinical trial is the amount of time needed to observe statistically significant differences in treatment outcomes among enrolled patients, known as the “follow-up period.” The length of the follow-up period largely depends on two factors: the natural progression of the disease, and the clinical trial endpoints required by government regulators. . . Conventionally, clinical trials evaluate whether a candidate product provides a clinical benefit to mortality—be it overall survival or a closely related measure such as “disease free survival,” which measures time until cancer recurrence. However, in recent years there has been increased interest in using surrogate endpoints as a substitute for the standard clinical endpoints in a drug trial. In the case of hypertension, for example, lower blood pressure is accepted as a surrogate for the clinical endpoint of preventing cardiovascular complications. . . blood cell counts and related measures have been accepted surrogate endpoints for hematologic malignancies (leukemias and lymphomas).”

[6] Thomas, David W., et al., “Clinical Development Success Rates 2006-2015,” Biotechnology Innovation Organization, June 2016, p.23.

[7] Thomas, David W., et al., “Clinical Development Success Rates 2006-2015,” Biotechnology Innovation Organization, June 2016, p.22.

[8] The complexity of the clinical trials results from a variety of factors including a shift in focus from acute to chronic illness, collection of increasingly intricate data elements, closer attention to each element of trial design, and concern about potential requests from regulatory agencies. Source: Getz, K.A., R.A. Campo, and K.I. Kaitin. “Variability in Protocol Design Complexity by Phase and Therapeutic Area.” Drug Information Journal, 2011, vol.45, no.4, pp. 413–420.

[9] Source: PhRMA. “Biopharmaceuticals in Perspective,” Spring 2013.

[10] Desmon, Stephanie. “Industry-financed clinical trials on the rise as number of NIH-funded trials falls: Researchers raise concerns about trends in research funding as commercial ventures run six times more trials than academic investigators,” The HUB at Johns Hopkins, 16 December 2015.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![Figure 2: Chart of LOA from Phase I, Displayed highest to lowest by disease area[4]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/lybecker-f-2-06-2016.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

9 comments so far.

Anon

June 8, 2016 10:54 amWe disagree on a fundamental level as to what “erosion” means.

The period of exclusivity is not different for different art fields – your wanting something different – something special simply needs to be looked at as exactly that: something different and something special.

Yes, I do see that because of the human interaction aspect, there are additional non-patent “limitations.” But please do not attempt to manipulate patent terms to “compensate” for non-patent terms and pretend that you are not already receiving special treatment that no other art unit benefits from.

That you have a certain degree of special treatment does not seem enough – you (the royal you) appear to just want to whine for more.

xtian

June 8, 2016 09:06 amAnon – I will address two points. First, holding a filing until later in development is legally impossible in the pharma space. Its not a competition issues, its an FDA/EMA issue. The FDA and EMA mandates all public disclosure of any drug being studied in man. The study must be registered with clinical trials.gov (public website) or equivalent EMA website and its result will be made public. Pharma is forced to publish its invention. Obviously then, patent filing must be made prior to in-man studies. This may be where you see companies get caught by filing too-early.

Second, I am confused. What is the “market preparation” bonus you refer to? I haven’t heard this term before. If you are referring to PTE, PTE isn’t a bonus. It is to recover lost patent term. I don’t know of any other industry that is not allowed to market its product (being “market ready”) until it receives government approval. Typically PDUFA dates (the FDA’s self-imposed timelines for approval (which they rarely meet)) run anywhere from 18-36 months from when the drug product is “market ready.” This would be like telling Apple that once you are ready to launch the new version of the iPhone (remembering that all specs about it have been made public), Apple must still wait 2.5 years for gov’t approval.

On one point we do agree on – Pharma does not compete on even terms. Pharma is a specific and unique industry where prior public policy decisions (FDA approval, forced publication via clinical trials.gov, encouragement of generic entry through the H-W process, etc.) have intentionally or unintentionally eroded patent term. We just disagree as to the favor-ability of those terms.

Anon

June 7, 2016 11:45 amItem caugh in filter – please release and remove this notice – thanks

Anon

June 7, 2016 11:43 amxtain,

Your arguments on “erosion” do not wash and actually make my case for me.

You confuse “market readiness” with the actual patent and that is purely a Pharma smokescreen.

No other industry – none – obtains any sense of “market preparation” bonus. All compete on even timing terms except Pharma.

Even the Bolar argument is not convincing as that exception is only a preparation for competition and has no actual impact on the term of exclusivity in the market (and is actually yet another argument for more than what any other art field provides, as you would have an effective term greater than 20 years.

If you don’t like the patent term being “eaten” with front end activities, do not file until those front end activities are complete. This of course is a different aspect of what strikes me as Pharma exceptionalism – I have seen too many failures of those front end activities that show that actual possession of utility is absent the too-early filing. I “get” the hurry to establish an earlier date than competitors, but you trade on additional fallacies as ALL Pharma competitors face that same aspect, so “exceptions” to having actual utility remains just that: exceptions.

Sorry, but the usual sound bytes of Pharma defense remain rather unpersuasive.

xtian

June 7, 2016 08:51 amAnon –

I agree that the “promotes copying” quid pro quo should be after the designated period of exclusivity. However, in pharma, the designated period of exclusivity has been eroded by various exceptions.

For example, in pharma, one exception is that your competitor is allowed to infringe your patents while your competitor developments a copy of your branded product (See Bolar and Safe Harbor Provision of §271(e)(1)). Another execption is that pharma has a specific statutory scheme to encourage copiers to challenge your patents (without even having an infringing product) four years after your launch your branded product (Hatch-Waxman). Does the aviation industry or agricultural industry exempt infringement of competitors during product development? Does the aviation industry or agricultural industry allow copiers to challenge patents without an actual case in controversy (that is, without a basis for a DJ action – a product made of threat of suit by the patent holder)?

Now, add to this the fact that the pharma industry must rely on another governmental agency before its product are allowed to be sold, a review period that eats up precious patent term (5 years PTE is a far cry from recovering this lost time). (I haven’t even mentioned IPRS!!)

What you get is a total package in the pharma industry that, in my opinion, is stacked against the “innovation side” and tilted towards the “promotes copying” side.

Because of this, I have seen articles say that the average period for exclusivity (your quid pro quo) enjoyed by a patented pharmaceutical composition is about 12 years, not the full 20 year term of the patent.

My point is, one must consider all aspects surrounding the pharma industry in any conversation regarding costs and public benefit.

T2

June 7, 2016 07:55 amI agree with anon @ 1, and imagine most practitioners would re the “costs too much” argument. The pharma sector is like any other. It takes investment to create any sort of business, and development times which span several years are not unique to Pharma. Should there be special IP giveaways for the space flight industry? How about the agricultural industry? No.

In the meantime, there have been a number of puzzling developments in the Pharma industry, including impressively high pricing (often borne by taxpayers and the national deficit) as well as company relocations to tax havens. I would like to see a study (funded by federal dollars or done by the Congressional Research Service) that looks at Pharma’s contribution to GDP over the years, and weighed against its costs.

Anon

June 7, 2016 05:40 amxtian,

I think that you have that “promotes copying” aspect a little over emphasized. The reason for the Quid Pro Quo in all art fields is to promote copying – after the designated period of exclusivity.

xtian

June 6, 2016 10:56 amAnon- no other industry has the development timelines and regulatory framework which promotes copying. Generics and biosimilars. Couple that with the difficulty in obtaining injunctions, and I would argue that no other industry has its competition forced on it the way pharma does.

Anon

June 5, 2016 11:19 amI am as pro-patent as anyone that you will ever find, but I find this type of “gee, this is expensive so on that account alone we need to have patent protection” to be at best problematic.

While I do “get” the “but for cost” rationale, I find that far too many people either:

– stop thinking critically and either assume that ONLY such “but for cost” should be a proper rationale for patent protection, or

– apply the “but for cost” in an entirely too broad and unthinking manner.

The first item is relatively self-explanatory.

The second item comes from the (possibly inadvertent) sheltering effect of a too broadly viewed “protection.” Protect too much of the development system, and you remove any natural competitive factors that aim to make that development system efficient. I have seen far too many internal documents in the Pharma world that simply “pad” the bottom line (with no care to development inefficiencies) with the “standard” argument that cost charged for a drug can be so much higher (and typically ONLY in the US – a separate but related aspect of geographical pricing is certainly in play) “because” of costly (inefficient) development.”standard practice.”

Open that “standard practice” – make it outside of patent protection, and you will see MUCH more effort going to innovate and develop efficient development techniques. NO OTHER industry is “coddled” in the manner that I see the Pharma industry coddled.