As first reported in Patently O, Jericho Systems Corp. has recently filed a petition for certiorari before the Supreme Court, asking the Court to review the abstract idea test as it has developed in and since Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank and Mayo v. Prometheus.

As first reported in Patently O, Jericho Systems Corp. has recently filed a petition for certiorari before the Supreme Court, asking the Court to review the abstract idea test as it has developed in and since Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank and Mayo v. Prometheus.

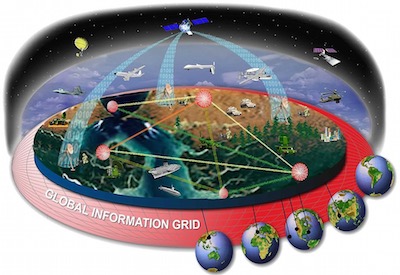

The patent at issue in Jericho, U.S. Patent No. 8,560,856, claims a specific system and method in which a user’s request to access information or perform an action is routed to a server which in turn calls up the rule associated with the request in real time rather than from a static database of rules. This method of security clearance was created in order to avoid the problems associated with the traditionally used system where a user tries to access information and the computer checks the list for access. If the user’s name is on the list, access is granted. If the user’s name is not on the list, access is denied. Jericho’s access control model was first used as the blueprint for the Department of Defense Global Information grid in 2007. The software was later deployed across two Department of Defense secure network enterprises, providing access control to over six million persons and entities. Five years later, President Obama mandated the use of this model in every U.S. Government enterprise.

This law suit commenced when Jericho learned that Axiomatics Incorporated and Axiomatics AB (“Axiomatics”) were using this technology to compete with Jericho for business with U.S. Department of Veterans Benefits. As most defendants do when facing a patent infringement suit involving software, Axiomatics asserted that the patent was invalid because it attempts to patent an abstract idea.

At issue here is claim 1, and its dependents, which discloses the following invention:

1. A method to process authenticated user requests to access resources, the method comprising:

receiving from a user a request to perform an action on a resource;

receiving by a server a rule associated with the action, wherein the server comprises a processor and operatively associated memory, and wherein the rule indicates conditions under which a request to perform the action on the resource should be granted;

determining a plurality of attributes required to evaluate the rule;

classifying at least a portion of the plurality of attributes by connector, wherein each connector is in communication with an associated remote data source comprising values for attributes classified with the connector;

for a first portion of the plurality of attributes classified with a first connector:

for each of the first portion of the plurality of attributes, determining whether an attribute value for the attribute is present at the server;

generating a first connector request, wherein the first connector request comprises each of the first portion of the plurality of attributes that lacks an attribute value at the server, and

requesting attribute values for each attribute included in the first connector request, wherein the requesting takes place via the first connector and is directed to the remote data source associated with the first connector;

evaluating, by the server, the user request to determine whether the user is authorized to perform the action on the resource, wherein the evaluation comprises applying the rule considering the values for the plurality of attributes; and

returning an authorization decision.

In analyzing the first part of the Mayo test, the district court agreed with Axiomatic’s reasoning that “the gist of the claim involves a user entering a request for access, looking up the rule for access, determining what information is needed to apply the rule, obtaining that information, and then applying the information to the rule to make a decision.” Axiomatic analogized this method with making a determination if somebody is old enough to buy an R rated movie ticket.

[Supreme-Court]

“In order to make this determination, one would have to determine the rule, which would be a person must be 17 to purchase an R rated movie ticket; 2) determine what information is needed to make a decision under the rule, which is the age of the person trying to buy a ticket; 3) retrieving the specific information about the person needed to make a determination, which is requesting proof of age; 3) [sic] applying that information to the rule, which may be yes the person is allowed to purchase the ticket because his age is 20.”

Jericho argued that the claims solve a problem rooted in modern computing, providing an example involving the use of the invention in a military defense scenario, in which the system could be used to make quick and efficient decisions regarding a person’s authority to access information. The district court dismissed this argument, stating, “even if the system is faster and more efficient than what was done in the past, that fact does not make this not an abstract idea. The idea behind the process remains that [sic] same.”

The District Court also found that Claim 1 did not pass the second part of the Mayo test. Jericho argued that the claims presented in the ‘836 patent were analogous to the claims presented in Research Corp. Techs. v. Microsoft Corp., where the Federal Circuit upheld the validity of the claims because they presented functional and palpable applications in the field of computer technology. Jericho argued that its claims were likewise patentable because they involve “an inventive concept that has many practical applications and represents a large functional improvement over prior methods.” The court ignored this argument, stating “[the ‘836 patent] simply uses standard computing processes to implement an idea unrelated to computer technology. It does not change the way a computer functions or the way the internet operates.”

Finally, the district court agreed with Jericho that claim 1 passed the machine or transformation test, however, the claim was still not saved. The court found that even if the claim only recites general computer functionality, the existence of the limitation that the process must be completed with a computer, present in the claim, indicates that the claim is tied to a particular machine. However, the court found that, as held in Alice v. CLS Bank, the recitation of generic computer limitations does not make an otherwise ineligible claim patent eligible.

Jericho has petitioned this case for writ of certiorari before the Supreme Court of the United States after the Federal Circuit upheld the district court’s ruling without an opinion in a Rule 36 summary disposition, which is something that the Federal Circuit does with regularity.

In the petition for certiorari, Jericho poses the question as to whether, under Alice and Mayo, a patent may be invalidated as an “abstract idea” under §101 when it claims a specific implementation and does not preempt other uses of the abstract idea.

Jericho argues that the Federal Circuit has struggled to apply the Supreme Court’s precedent concerning the “abstract idea” exception to patentability. In the wake of Alice, courts have struggled with the test for “generic computer implementation.” As the Federal Circuit precedent suggests the entire §101 analysis is a question of law, the lower courts routinely decide whether a computer implementation is “conventional” or “unconventional” without receiving evidence or expert testimony. Jericho argues that this approach cannot be reconciled with the Supreme Court’s detailed analysis of the improvements made to existing art in step two in the Mayo test.

This case could be the one patent attorneys have been waiting for following the aftermath of Alice and Mayo. As Jericho has argued, this case is an appropriate vehicle for addressing the recurring question concerning the proper application of Alice. This case involves a single issue and, as a result, no additional legal or factual issues would complicate the Supreme Court’s analysis. It would be very interesting and particularly telling for the Supreme Court to consider whether an invention that is acknowledged to make a system operate faster and more efficient is, in fact, not patent eligible. In the real world inventions of that type are patent eligible. Thus, this case could force the Court to address issues it has previously attempted to avoid when dealing with computer implemented innovations.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

5 comments so far.

Jim Ruttler

June 24, 2016 05:48 pmTernary @3. I agree with the following statement “One may question the wisdom of drafting the claims in the manner as used. However, the subject matter is clearly technical”.

However, I would just add that while the claim language may not be desirable now, it was the type of claim language that was clearly patent eligible when granted.

The fact that the Supreme Court can retroactively change patent law makes it difficult to plan for the future when the PTO takes 3 years to grant a patent outside the accelerated review option. Likewise, it is difficult for owners to understand how they can be penalized for following the law as it was written when they had a chance to draft the application and claims.

It would be one thing for the Court to make this abstract test applicable to applications filed on or after the decision, but it is disruptive and unfair to retroactively change the law.

This is especially true when coupled with the no actual right to amend during IPR proceedings.

Obviously, moving forward – more applications and more continuations will have to be filed to guard against retroactive modifications to the law by unelected judicial officers.

Paul Morinville

June 23, 2016 12:51 pmThere is a long history of failed access control systems prior to this invention. These security issues brought enormous administrative overhead, lost and stolen data and lawsuits. This invention is not an inconsequential reason the Identity and Access Management industry now works. It is appalling to me that this would be found abstract. It is not possible for an abstract idea to change the physical world – this invention does that.

Ternary

June 23, 2016 12:34 pmThis really is becoming a miserable “gotcha” business.

In the context of the specification, the invention clearly is directed to machine security based on “dynamic enrichment of data” within an “HTTP/XML RPC architecture” embodiment. The invention is utterly and expressly machine directed and has absolutely nothing to do “buying an R-rated movie.” In fact, the spec explains how it improves security in Enterprise Systems without having to implement executable code.

One may question the wisdom of drafting the claims in the manner as used. However, the subject matter is clearly technical.

Ternary

June 23, 2016 12:14 pmAudrey, you linked to the wrong patent: 8,560,856 is a Futurewei patent related to cryptographic methods including Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC).

But your inadvertent mistake is relevant in view of Alice. ECCs are heavy on math and are probably much more “abstract” than the Jericho patent (which is S/N 8,560,836). However, I suspect that the courts will stamp the Futurewei patent as “claiming significantly more” or even “improving the working of the computer” as there is no equivalent to “buying an R-rated movie” in ECC.

Paul Morinville

June 22, 2016 03:13 pmThis issue must be resolved. If it is not, it is resolved that there is no patent system for software, which is more than half of all issued patents.