For many, allergies are a seasonal nuisance, but allergic reactions to certain foods or chemicals can be fatal for some. In serious cases of severe reactions, anaphylaxis can develop. In anaphylactic shock, a person suffering an allergic reaction can experience symptoms such as narrowed breathing airways, a swift drop in blood pressure and nausea. These conditions are caused by the rush of chemicals released by the body’s immune system in response to encountering the substance triggering the allergy, whether that substance is introduced through eating food, an insect sting or simply close contact to the trigger.

Food allergies affect 15 million people in the United States according to statistics published by Food Allergy Research & Education (FARE). The effects of severe food allergies are toughest on younger patients and one in 13 children under the age of 18 suffer from such a condition. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the prevalence rate for food allergies among children under 18 rose by 18 percent during the decade between 1997 and 2007. FARE reports that allergies cause 200,000 emergency room visits each year, approximately once every three minutes, as well as 300,000 ambulatory-care visits for those under the age of 18. Some reports indicate that each year, 200 deaths in the U.S. are attributable to anaphylaxis.

When a person is suffering a severe allergic reaction, one of the only methods he or she has to keep symptoms from growing into a dangerous condition is a quick injection of epinephrine. Epinephrine is a synthetic form of adrenaline which counteracts the drop in blood pressure, relaxes lung muscles for greater breath intake and increases heart rate. This year, the National Inventors Hall of Fame inducted one of the masterminds behind the first line of defense most people have against serious complications from allergies: the EpiPen.

This June 28th marks the 49th anniversary of the date of issue of the patent for which Sheldon Kaplan has been inducted into the Hall of Fame. Today, we return to our Evolution of Technology series here on IPWatchdog to take a longer look at how epinephrine use for allergy treatments developed and the breakthrough in medical device design which has helped to save many lives.

The Discovery of Epinephrine and Its Effects on the Human Body

The early days of epinephrine involve work from a collection of physicists and physiologists working near the turn of the 20th century. In the 1890s, English physiologists George Oliver and Sir Edward Albert Sharpey-Schafer are credited with having noted the effects of a substance found in animal adrenal glands on blood pressure. Within a few years, the purest form of adrenaline was isolated by Japanese biochemist Jokichi Takamine. Many online information sources note that this is the first hormone which was both isolated and artificially synthesized.

The intellectual property crowd may be interested to note that Takamine actually received the first U.S. patent claiming a microbial enzyme. On September 11th, 1894, Takamine was issued U.S. Patent No. 525823, titled Process of Making Diastatic Enzyme. It protected a process of mixing broken grains of cereals from which starchy material has been removed with spores from a fungus at a certain temperature for abundant fungus development, and then extracting soluble matter with water and precipitating the matter with alcohol. While not directly related to Takamine’s work with epinephrine, it does highlight a long-time interest in enzyme production by the biochemist.

Of much more relevance is a patent issued to Takamine in June 1903: U.S. Patent No. 730176, entitled Glandular Extractive Product. This claimed a substance exhibiting physiological characteristics and reactions of the suprarenal glands in a stable, concentrated form which is practically free from inert and associated gland tissue. The suprarenal gland, now also known as the adrenal gland, rests above the kidneys; this is how epinephrine, an anglicized Grecian word for “above the kidneys,” got its name.

Although the science behind why epinephrine worked wouldn’t be cleared up for decades, Takamine licensed his related patents to Parke-Davis, at the time one of America’s largest pharmaceutical firms, now a subsidiary of Pfizer (NYSE:PFE). Parke-Davis marketed the substance as Adrenalin and engaged in a major patent infringement lawsuit which continues to reverberate in American district courts. Parke-Davis & Co. vs. H. K. Mulford Co., a case in which Parke-Davis alleged infringement of the ‘176 patent, was argued in the Southern District of New York in 1911. The court largely upheld the ‘176 patent. This case is sometimes cited in legal documents related to court cases involving the patentability of products existing in nature, including the recent Association for Molecular Pathology vs. Myriad Genetics; it’s interesting to note that, even a century later, our country still grapples with the issue of patenting biological materials.

Why epinephrine works in the way that it does to stop allergic reactions wouldn’t truly be understood until the 1960s, beginning with the work of American biochemist Robert Lefkowitz. In the late 1960s, Lefkowitz studied the interaction of hormones with receptor cells inside the body by attaching radioactive isotopes of iodine to different hormones. By tracking the radioactive iodine, Lefkowitz got the world’s first glimpse at how adrenaline worked in the human body. In the 1980s, after being joined by biochemist Brian Kobilka, the team saw that adrenaline was taken up by cells known as G-protein-coupled receptors, a group of receptors which had never before been identified. Kobilka further identified the sequence of the human genome which codes for G-coupled-protein and other receptors throughout the human body. In 2012, the two were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work.

The Quick-Acting EpiPen Saves More Lives

Despite the progress in understanding how a dosage of epinephrine can improve a person’s condition at critical times, administration of the substance was still a very primitive business. Epinephrine must be administered as quickly as possible during a severe allergic reaction for the best outcomes. However, the business of measuring out a dose of adrenaline, drawing it up into a syringe and then administering the medication requires extra steps and wastes time, putting anyone suffering from anaphylactic shock in further risk.

An early device for the quick injection of epinephrine into a patient was the Ana-Kit which provided a pre-measured dose of one milligram of epinephrine in a water solution contained by a syringe. Ana-Kits were in use by those with allergies to food, bee stings or certain drugs. According to a licensed pharmacist’s report on the online health information platform Sharecare, Ana-Kits are no longer available to be prescribed in the United States.

There were plenty of drawbacks to conventional autoinjectors during the time of Sheldon Kaplan. Many such devices were composed of stainless steel, which could react with some drugs and make them lose their stability. By the early 1970s, Kaplan had conceived of a glass container which was able to hold a wider range of drug compounds without reacting while also delivering larger amounts of medication. At the time he was working for Bethesda, MD-based Survival Technology, Inc., which was approached in 1973 by the Pentagon; the military agency was looking for a method for delivering a nerve agent antidote which was unstable in stainless steel.

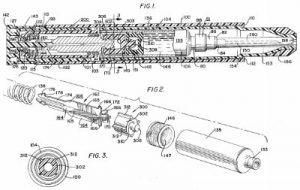

The benefits of the EpiPen are reflected within U.S. Patent No. 4031893, entitled Hypodermic Injection Device Having Means for Varying the Medicament Capacity Thereof and issued June 28th, 1977. It protected a hypodermic injection device having a gun with a sleeve open at one end, and then a cartridge holder within the gun and a plunger within the sleeve. The device also had spring power and restraining means for controlling plunger movement as well as a means by which the position of the plunger could be adjusted to change the amount of medicament carried in the syringe. The patent notes the advantages of the ability to adjust the amount of medicament without revising the other components of the autoinjector device: “The economics possible by this invention will be significant.”

The benefits of the EpiPen are reflected within U.S. Patent No. 4031893, entitled Hypodermic Injection Device Having Means for Varying the Medicament Capacity Thereof and issued June 28th, 1977. It protected a hypodermic injection device having a gun with a sleeve open at one end, and then a cartridge holder within the gun and a plunger within the sleeve. The device also had spring power and restraining means for controlling plunger movement as well as a means by which the position of the plunger could be adjusted to change the amount of medicament carried in the syringe. The patent notes the advantages of the ability to adjust the amount of medicament without revising the other components of the autoinjector device: “The economics possible by this invention will be significant.”

The U.S. military was interested in such an innovation to protect its soldiers respond to biochemical attacks but Kaplan soon saw how useful this device could be for consumers. He was also interested in improving his designs over the years, as is evidenced by U.S. Patent No. 6767336, entitled Automatic Injector and issued to Kaplan in July 2004. This protected an automatic injector with an improved configuration that reduced the chances of a premature deployment of the cannula which is to be inserted into a person’s skin.

The EpiPen continues to be a highly sought consumer medical device. Last September, Bloomberg reported that EpiPen sales had eclipsed $1 billion per year, proving to be a true cash cow for current owner Mylan (NASDAQ:MYL). According to Kaplan’s biography in his National Inventors Hall of Fame listing, he would also go on to a medical kit for NASA’s Apollo missions as well as a pneumatic medical dressing for pilots flying reconnaissance missions. But Kaplan’s claim to fame, the EpiPen, stands in a class by itself in the world of commercially successful medical device inventions.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[[Advertisement]]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-banner-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-938x313-1.jpeg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

2 comments so far.

Bucky Katt

August 23, 2016 04:21 pm1977 was 39 years ago, not 49.

Paul Cole

June 28, 2016 05:26 pmWith reference to the s.101 debate, it should not be forgotten that adrenaline is a naturally occurring material, although it was claimed in stable and concentrated form. If the patent came before the Federal Circuit today, what would the judges make of it?

I think the courts had much better attitudes 100 years ago.