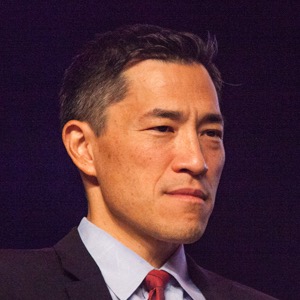

Judge Raymond Chen of the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, October 2015 at the AIPLA annual meeting.

Earlier this week the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit issued a decision in BASCOM Global Internet Services, Inc. v. AT&T Mobility LLC. Writing the opinion for the majority was Judge Raymond Chen, who also authored the Court’s decision in DDR Holdings, which is one of the few cases to similarly find software patent claims to be patent eligible. Joining Chen on the panel were Judges O’Malley and Newman, with Judge Newman concurring and writing separately. The good news for those who believe software should be patent eligible is that this represents yet another data point on the software can be patent eligible map.

Procedure on Motions to Dismiss

This case arrived at the Federal Circuit on an appeal brought by BASCOM from the district court’s decision to grant a motion to dismiss under Rule 12(b)(6). In the majority opinion Chen made much of the civil procedure aspects of a 12(b)(6) motion, as well he should.

Frankly, it is about time that the Federal Circuit notice that these patent eligibility cases are reaching them on motions to dismiss. This should be overwhelmingly significant in virtually all cases given that a motion to dismiss is an extraordinary remedy in practically every situation throughout the law. Simply put, judges are loath to dismiss cases on a motion to dismiss before there has been any discovery or any issues are considered on their merits. That is, of course, except when a patent owner sues an alleged infringer.

Where a patent owner sues for patent infringement many district court judges become suddenly all too willing to dismiss the case straight away without giving the patent a presumption of validity (despite what 35 U.S.C. §282 directs by its plain language) and without ever construing the patent claims. How can you possibly know whether a patent claim is patent eligible if you don’t construe the patent claim in order to determine what the invention is that is being claimed?

Never mind that it is logically (and factually) impossible to know what is being claimed without construing the claims, it has become commonplace for district courts to dismiss patent infringement lawsuits on a motion to dismiss while at the same time ruling the patent claims ineligible. All of this is done with no consideration of the merits of the case or the substance of what is being claimed. There has been no discovery, no claim construction and on a motion to dismiss the procedural laws forbid consideration of the merits.

Shocking, isn’t it? The merits of the patent owner’s case does not matter at all on a motion to dismiss, yet the merits of the patent claims that won’t ever be construed by the judge do matter. To call the deck stacked against the patent owner doesn’t begin to capture the procedural unfairness at play.

In any event, in the majority decision Chen went to great lengths to explain that the Court was giving all inferences to the nonmoving party (i.e., the patentee). In other areas of federal litigation this would not be noteworthy simply because that is what the law commands. In the patent sphere, however, the patent owner seems to rarely, if ever, be afforded even the most basic procedural rights available to all other litigants. To call patent owners second-class citizens in the eyes of much, if not most, of the federal judiciary is not a stretch. Sadly, it is a reality.

Chen is certainly right to point out the procedural posture, which many in the patent community have been talking about for some time, but to my knowledge this is the first decision to actually apply basic civil procedure protections in the context of a 12(b)(6) motion that argues patent claims are ineligible. Thus, I think the story of BASCOM will be written only once we know whether other panels of the Federal Circuit begin to enforce the most fundamental rules of civil procedure, and also once we known whether district courts actually get the message.

The Invention

The invention described in U.S. Patent No. 5,987,606, relates to a method and system for content filtering information retrieved from an Internet computer network. The patent explains that the advantages of the invention are found in the combination of the then-known filtering tools in a manner that avoids their known drawbacks. The claimed filtering system avoids being “modified or thwarted by a computer literate end-user,” and avoids being installed on and dependent on “individual end-user hardware and operating systems” or “tied to a single local area network or a local server platform” by installing the filter at the ISP server. Thus, the claimed invention is able to provide individually customizable filtering at the remote ISP server by taking advantage of the technical capability of certain communication networks.

The claims of the ’606 patent generally recite a system for filtering Internet content. The claimed filtering system is located on a remote ISP server that associates each network account with (1) one or more filtering schemes and (2) at least one set of filtering elements from a plurality of sets of filtering elements, thereby allowing individual network accounts to customize the filtering of Internet traffic associated with the account.

Patent Eligibility

The Alice/Mayo framework adopted by the United States Supreme Court requires reviewing courts to ask and answer a series of questions before determining whether a patent claim constitutes patent eligible subject matter. The first question is whether the patent claim covers an invention from one of the four enumerated categories of invention defined in 35 U.S.C. §101 (i.e., is the invention a process, machine, article of manufacture, or composition of matter). If the answer to this question is no then the patent claim is patent ineligible. If the answer is yes, as it was in the case of the claims for the ‘606 patent, move on to the next inquiry.

The second question asks whether the patent claim seeks to cover one of the three specifically identified judicial exceptions to patent eligibility. Although there is absolutely no textual support for the creation of any judicial exceptions to patent eligibility, the Supreme Court has long legislated from the bench and ignored the clear language of the statute. The three identified judicial exceptions are: laws of nature, physical phenomena and abstract ideas. If the claim does NOT seek to protect one of those judicial exception then the claim is patent eligible, as was the case in Enfish v. Microsoft. In this case, the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that the filtering of content is an abstract idea because “it is a long-standing, well-known method of organizing human behavior, similar to concepts previously found to be abstract.”

In the case where the patent claim seeks to cover a judicial exception to patent eligibility, the final question asks whether the inventive concept covered in the claimed invention was “significantly more” than merely the judicial exception. In this case, the question was whether the claim added significantly more such that more than a mere abstract idea would be captured. The Federal Circuit ruled that the claims did add significantly more and, therefore, the claims are patent eligible.

Of course, it is worth reminding everyone that no court – not the Supreme Court and not the Federal Circuit – has ever defined the term “abstract idea” or the term “significantly more.” As such, both remain properly characterized as a “we know it when we see it” undefined standard.

Conflating Obviousness with Patent Eligibility

Perhaps one of the most significant aspects of the Federal Circuit decision in BASCOM is that the Court explained that the district court’s analysis conflated obviousness with patent eligibility. This is hardly a unique observation, or a one-off problem. In fact, the Supreme Court’s decision in Mayo v. Prometheus actually mandates the conflating of obviousness (and novelty) with patent eligibility. What is unique here is that the Federal Circuit has called it out for what it is – inappropriate.

“The district court’s analysis in this case, however, looks similar to an obviousness analysis under 35 U.S.C. §103,” explained Judge Chen in the decision. Indeed, it does look similar to an obviousness inquiry in some ways, but without any of the limitations or protections limiting how and under what circumstances a proper combination can lead to a conclusion of obviousness. In other words, when obviousness is conflated with patent eligibility the test becomes even more subjective and is wholly without boundaries.

“The inventive concept inquiry requires more than recognizing that each claim element, by itself, was known in the art,” Chen explained. “As is the case here, an inventive concept can be found in the non-conventional and non-generic arrangement of known, conventional pieces.”

Judge Chen would go on to explain that the inventive concept of the ‘606 patent “is the installation of a filtering tool at a specific location, remote from the end-users, with customizable filtering features specific to each end user.”

Ultimately, the Federal Circuit held that the “claims do not merely recite the abstract idea of filtering content along with the requirement to perform it on the Internet…Nor do the claims preempt all ways of filtering content on the Internet.”

Newman concurrence

Judge Pauline Newman of the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, October 2015 at the AIPLA annual meeting.

In a concurring opinion Judge Newman wrote that she sees no good reason why district courts should, or must, start cases by determining whether patent claims are patent eligible. Newman sharply criticized (although not as sharply as she can criticize at times) the practice of piecemeal litigation. Judge Newman explained: “Initial determination of eligibility often does not resolve patentability, whereas initial determination of patentability issues always resolves or moots eligibility.”

Judge Newman is, of course, correct. The problem, however, is that disposing of patent infringement litigation on a motion to dismiss has nothing to do with proper administration of justice. The disposition of patent infringement litigation on a motion to dismiss has everything to do with tilting the playing field and rigging the system in favor of the defendant. Nowhere else in the law is it so easy for a defendant to prevail on a motion to dismiss. But the Supreme Court seems to want district courts to dispose of patent infringement cases without ever considering the merits of the case, without construing the claims, without providing a presumption of validity, and without giving the owner of a constitutionally protected property right their day in court.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Quartz-IP-May-9-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

26 comments so far.

Night Writer

July 5, 2016 12:16 pm@25 step back: I agree with your spirit post. In fact, I have said many times that Stevens dissent in Bilski is based on his belief that he has a spirit that does the actually thinking without his brain.

step back

July 5, 2016 10:48 amIn reality Alice overturns the US Constitution.

All is forgiven though because Clarence and his fellow clowns speak in the “natural” language of spirituality.

Who needs science when the spirits of the woodlands flow through our Medieval corpi?

http://patentu.blogspot.com/2016/06/spirit-town.html

Night Writer

July 5, 2016 10:04 amThe reality is that Alice overturns KSR. Ignoring that is one of great intellectual lies of patent law.

Night Writer

July 3, 2016 02:25 pmThe biggest thing to consider is that the lowly like Edward says that “business method” patents should not be eligible and yet the software industry in the US is 10 times bigger and probably a factor of 100 times better than any other country. It has grown up and matured with patents. And, yet we are supposed to believe that now they are toxic and should be eliminated.

But—note that none of these low lives every explain how it is that the software industry outshines every other country by at least a factor of 10 with the patents.

Night Writer

July 3, 2016 01:30 pm@21: the reality is that it is impossible to have a discussion on patent law with the likes of Edward Heller or Richard Stern. It is not just patent law. It is the zeitgeist where it is somehow OK (meaning you can sleep at night) to be disingenuous as long as you are doing it for your money or some cause that is supposedly righteous.

Anon

July 3, 2016 12:07 pmNight Writer,

It is not without a healthy dose of irony that I note that it was Ned Heller himself who once posted a link to a pay-walled article by Court of Appeals of the Federal Circuit Judge O’Malley in which Judge O’Malley was extremely critical of “amici” constantly urging the court to BE in that same “activist” mode.

The irony of course is captured in my post at 18. This (self-induced) blindness shows itself based on what Mr. Heller would want the law to be, and not as what the law actually is (in regards to software and business method patents). To reach that point of what Mr. Heller wants, he requires that the Court BE active and to re-write the words of Congress (either implicitly, explicitly, or both).

As I have pointed out, the doctrine of separation of powers is NOT limited to a battle between any single set of just two branches of the government. Ned is involved in a battle between the Executive Branch and the Judicial Branch (as he sees it). His myopia prevents him from seeing that a fundamental issue exists with the Legislative Branch. His myopia further exacerbates his elevation of the Judicial Branch to be a branch (but only at the Supreme Court level) to be ABOVE the Constitution.

The Constitution (itself) is NOT what the Supreme Court says it is. This is remarkably different than the Supreme Court weighing in on a law (direct or interpreted) that Congress writes and judging whether the law that Congress wrote passes Constitutional muster.

For all of Mr. Heller’s vaunted knowledge of history, he displays an alarming lack of knowledge of the concerns of the Founding Fathers towards an unchecked Judiciary.

When one takes a step back, and reviews Mr. Heller’s words in the larger contexts, One sees an inconsistent application of legal principles.

That is why I state that it is sad that we (the royal we) find ourselves in a potential situation of having Mr. Heller be a “champion” in a battle of Constitutionality of the AIA. There is a very real conflict in the larger view that may (just may) impact the more concentrated issue that Mr. Heller addresses. I certainly hope that it does not, but as is abundantly witnessed in many conversations on this and other legal forums, there is a definite weakness that comes from Mr. Heller’s inconsistent approach to the sanctity of the Rule of Law and having all three branches of the government held in check under the Constitution.

Night Writer

July 3, 2016 10:18 amI’ve notice Anon that each time I read and/or speak with an examiner about some twisted ridiculous argument why a claim fails 101 that I remember the anti-patent judicial activists like Ned. I think of the great waste of time and how this is not law nor science. Ned is following the worst person that has ever existed in patents–Richard Stern who wrote Benson. Both are disingenuous judicial activists.

Night Writer

July 2, 2016 09:50 amIt is tiring reading Edward’s propaganda.

Anon

July 1, 2016 09:54 amNight Writer @ 14,

I would take your view one step deeper: the problem is that patents for discovery are allowed per the Constitutional, and this fact is reflected in the words of Congress (the branch of the government authorized to write patent law under the Constitution), and it is only the arguably ultra vires actions of a single branch attempting to put into writing (often implicitly, but of late including explicitly) a different version of patent law that does not – and cannot – trace authority to either the Constitution or the words of Congress. The only “authority” it references is a self-reference that seeks to rewrite history and pretend that the Act of 1952 never happened (or at the minimum, only happened to reinforce the “judicial viewpoint.”

This willful attempt to rewrite history and elevate the judicial power of common law above the proper Constitutional allocation of statutory law to the legislative branch is an affront to the very basics of Constitutional power, statutory law and this country’s set up of limited powers for all branches of the government – and this limitation is expressly meant to include the judicial branch (there are many early writings warning of a unconstrained judicial branch).

Sadly, one “champion” of this unconstrained “judicial power” is the very person who quite possible has a real shot before the Supreme Court to present a clear separation of powers argument.

That would be Ned Heller.

I say sadly because I believe that Mr. Heller has conflicted himself out of fully pursuing a separation of powers argument in that he only views his own battle as a separation of powers between the branches of the Executive and the Judicial instead of separation of powers by and between ALL three branches.

His views in his case seem to be reinforcing some type of exception to the separation of powers and elevating the judicial branch above the constraints of the Constitution, as can be seen in his treatment on the present issue.

This also appears to hinder his ability to focus on the “right question” in his perceived battle of separation between the Executive and the Judicial (that right question is not focused on the battle between the Executive and the Judicial, but rather is focused on the third remaining branch).

In a comprehensive view of the separation of powers and the notion that NO branch is itself above the Constitution, each of these (long running) legal concepts can be seen to merge, or at least intersect to a significant degree:

A) Mr. Heller’s possible shot before the Supreme Court: Property – public or private (personal) of a patent, which is clearly – and even explicitly – set forth as personal and thus private.

B) This thread’s topic and the battle between judicial authority to write common law as opposed to when such authority is absent, as in Statutory Law – and in the history of patent law, the limiting fact that any pre-1952 grant of authority to another branch (common law) was rescinded in 1952 when Congress decided to pursue a different path.

C) And circling back: Not even the legislative branch writing patent law (their domain) may write such law on such a thing as property that violates OTHER Constitutional protections. This is reflected in that the AIA did not hide any elephants in mouseholes and change the very basic fact that a patent is property (as Mr. Heller notes, “not a privilege, revokable at will by the State“) and the item Mr. Heller has not grasped – that a full taking of the bundle of sticks of property (or even of the main stick of exclusivity) is not required for a violation of takings.

Yes, such a thing as taking of that exclusivity may be considered to be a violation of takings (as Ron Katznelson has recently pointed out to Mr. Heller), but it is simply a mistake to think that takings must reach that level to be a violation.

Hence, the applicability of takings to the Congress-authorized level of the initiation decision alone – and NOT dependent on any further adjudication on the merits – is sufficient in and of itself to be asked of the Court to point out that it is the Legislative Branch that has written a patent law that fails other constitutional protections.

Again, sadly, Mr. Heller has conflicted himself out from a full discussion of these things because he WANTS the Supreme Court to be above the Constitution in order for his other philosophical ends (the ending of software [as a manufacture and machine component] and business method patents). These ends require Mr. Heller to place the Supreme Court above the Constitution in order for the Court’s own self-referential ‘authority’ to reign supreme over the plain words of either the Constitution or the words of Congress.

Night Writer

July 1, 2016 09:25 am@15 Anon: Edward is tiring. He is like a propaganda machine. The only reason I can think that a practicing attorney would write the garbage that Edward does is to try to drum up business. My guess is that he is trying to suck up to the source of all evil in patent law, i.e. R. Stern. Probably an acid test to getting work is that you have to spout his nonsense.

Night Writer

July 1, 2016 09:21 amSo, I think the law is if the SCOTUS can figure out or understand the relationship between the invention and some relationship that they believe is a natural law, then it is not patentable.

Anon

July 1, 2016 09:16 amMr. Heller @ 13 – the best takeaway from your long example is that you are actively conflating patentability and eligibility.

You quite missed the point supplied by Mr. Cole that a fully patent eligible claim may come from fully non-patentable elements.

You may have seen this point previously under a different label: the label of the “Point of Novelty” is a canard for 101 purposes.

Any Rule of Law must reflect the point that Mr. Cole actually supplies (the point hat you gloss over in your conflation efforts).

Night Writer

July 1, 2016 08:56 am“There is no doubt that the Federal Circuit and the Supreme Court understood the Sequenom process to be effectively a request to patent the discovery that maternal plasma contained fetal DNA. I think we need to accept that.”

The problem with this reasoning is that any invention can be reduced to an attempt at patenting a law of nature.

Edward Heller

July 1, 2016 08:46 amPaul @ 11, regarding “directed to,” now I begin to see why Sequenom lost — it made virtually the same argument that CIPA made.

First, cooking eggs. It is easy to see that the process is not directed to a product of nature, the egg, the input, but to the cooked egg, the output. To suggest to the Supreme Court that the Alice test would or could result in a determination that the process was directed to a the egg input, a product of nature, would be in the nature of an insult to the Supreme Court. I can see how they could take offense.

Now take again the cooking eggs example and instead claim that the input was not eggs generally, but eggs from a specific beast. Is this process directed to cooking eggs or is this process directed to cooking eggs of a specific beast? The answer seems obvious. But why is it obvious – because the only thing new is the input. The output varies in a predictable way based upon the input. Thus the patentability of this claim would depend upon the input, unless the output produced an unexpected product such as gold, not cooked eggs.

Now assume it was the law that one cannot claim an old process, like cooking eggs, applied to a new input unless the output changed in an unexpected way. Applying the cooking eggs process to eggs of a specific beast would not produce a patentable invention even though strictly speaking the output was different. It was not different in kind. To allow a patent on such a thing would not be “directed” to a patent on a new process, but on the routine use of an old process.

Now in the case of Sequenom, the amplification process itself I believe was old, like cooking eggs. It was applied to a new input, maternal plasma. But the output of the process applied to maternal plasma was entirely predictable, was it not? The patentability of this claim cannot be justified on the basis of the process or the product because the process was old and the product entirely predictable.

There is no doubt that the Federal Circuit and the Supreme Court understood the Sequenom process to be effectively a request to patent the discovery that maternal plasma contained fetal DNA. I think we need to accept that.

So, the best argument to the Supreme Court and to Congress would be that the useful Arts are advanced by the promotion of the discovery of new phenomena of nature that are useful. It is not advanced by some criticism of the Supreme Court (or of the Federal Circuit) that its Alice test is wrong, or that it is acting in unconstitutional matter in not recognizing the patentability of discoveries of phenomena of nature, or the like. The argument has to be made to the Supreme Court that it should overrule its prior decisions that discoveries of phenomena of nature cannot be patented. The same argument could be made to Congress.

Anon

July 1, 2016 07:41 amPaul @ 11,

Thank you for pointing out yet another foible from the Court. The pet phrase “directed to” can be seen to be just another version of the “Gist” effect.

We – the royal we – have seen this before in history. The days leading up to the Act of 1952, to be precise.

Appearance of @ 8,

It is no mistake that see 103 there. The historical lesson learned – as actually enacted by Congress was to take from what was a single paragraph and turn that single paragraph into multiple sections of law including the new path of 103 instead of playing with Court attempts to define (or as the case may be to prevent bright line definitions of) the word “invention,” and a host of related words for that legal concept.

Paul Cole

July 1, 2016 03:30 amIf you are looking for vague language, the phrase “directed to” in the first part of the Mayo/Alice test is a paradigm example.

The EPI brief in Sequenom discusses the eligibility of a process for cooking an omelette. The process starts with eggs, it ends with an egg product and therefore, on the reasoning of the panel opinion in Ariosa it is directed to eggs, a natural product. On this analysis the transformative nature of the cooking process and the improvement in palatability that results is ignored. In Sequenom, the DNA amplification step corresponds to a cooking step and is transformative insofar as it enables the paternal DNA to be tested, which the naturally occurring material (in far lesser abundance) is not. The mere fact that a claim involves software or a natural product does not mean that it is “directed to” these things any more than a method of cooking an omelette which involves eggs means that the process is directed to eggs, and established case law applies this criterion with an unduly low level of discrimination.

The CIPA brief in Sequenom also argues that for an ordered combination new function or result is evidence of invention, and that this evidence is as applicable under 101 as it is under 103. The correctness of that argument is recognised in the present decision, which very clearly is a step forward. The key language, as pointed out above is that: “The inventive concept inquiry requires more than recognizing that each claim element, by itself, was known in the art. As is the case here, an inventive concept can be found in the non-conventional and non-generic arrangement of known, conventional pieces.” and that “As explained above, construed in favor of BASCOM as they must be in this procedural posture, the claims of the ’606 patent do not preempt the use of the abstract idea of filtering content on the Internet or on generic computer components performing conventional activities. The claims carve out a specific location for the filtering system (a remote ISP server) and require the filtering system to give users the ability to customize filtering for their individual network accounts.”

If the CAFC started to go further and pay attention to the wording of the statute, matters might be even further improved.

step back

July 1, 2016 03:27 ampatent leather @9,

Re McRO (Planet Blue), lip syncing is a fundamental practice as old as the human race and even before (monkey see, monkey do). Therefore it is conventional and abstract. The mere use of a computer (“apply it”) is not something significantly more to convert a parroting activity (lip syncing) into a searched-for “inventive concept” per Alice step 2. Ergo, ineligible.

/end sarcasm (Did you honestly think I was channeling Judge Lourie?)

Yes? ROFLMMLO (Rolling on Floor Laughing My Monkey Lips Off)

patent leather

July 1, 2016 01:55 amGreat news and good report. This case wasn’t covered by the “other” patent blog. Although these three judges are probably the most pro-software right now at the CAFC, so the patentee lucked out. I’m also looking forward to the McRO (Planet Blue) decision which should be out soon.

Appearance of …

June 30, 2016 09:03 pmThis looks like an important decision to me. In some respects, it “defuses” much of the impact of Alice by turning the Alice 2nd step into a redundant 35 USC 103 test, which patents had to satisfy anyway.

step back

June 30, 2016 06:12 pmGene @3,

I for one, submit that there is nothing reason-based or “reasonable” about the latest linguistic machinations of SCOTUS’s Alice/Mayo decisions. A bunch of mind melters (a.k.a. “friends” of the court) have bamboozled the courts and everyone else into believing in a spirit world populated with “nature”, “natural phenomenons”, “abstract ideas” and “natural laws”.

Who do the voodo that we do of late? It’s all happening in Spirit Town:

http://patentu.blogspot.com/2016/06/spirit-town.html

Night Writer

June 30, 2016 01:41 pmWith friends like Edward who needs enemies. Edward believes that Alappat should be expressly overturned. And if you question Edward you will find that he adheres closely to Benson. So, I would recommend not trusting anything he writes because he slips in there his witch reasoning with regularity.

See Alappat, 33 F.3d at 1544 (“Although

many, or arguably even all, of the means elements

recited in claim 15 represent circuitry elements that

perform mathematical calculations, which is essentially

true of all digital electrical circuits, the claimed invention

as a whole is directed to a combination of interrelated

elements which combine to form a machine for converting

discrete waveform data samples into anti-aliased pixel

illumination intensity data to be displayed on a display

means. This is not a disembodied mathematical concept

which may be characterized as an ‘abstract idea,’ but

rather a specific machine to produce a useful, concrete,

and tangible result.” (footnotes omitted)); see also id. at

1545 (“We have held that such programming creates a

new machine, because a general purpose computer in

effect becomes a special purpose computer once it is

programmed to perform particular functions pursuant to

instructions from program software.”).

Night Writer

June 30, 2016 01:31 pm@2 Edward:: You just never let up. “as opposed, to an improvement in business methods.” So, now according to you there are improvements to the functioning of computers and all the rest is a business method.

Again, what we have is witch arguments. You have no basis for your statements and you do like they do in witch trials. You come up with some name for something and then say that it is that name.

Edward really painful to read your garbage.

Mark Nowotarski

June 30, 2016 01:25 pmThis is a very helpful decision for both applicants and examiners. The court has said that statutory subject matter can be found in claims directed to a “specific technical solution” even for a business method. The court then said that the inventive concept “can be found in the non-conventional and non-generic arrangement of known, conventional pieces” and that “a software based invention” is adequate.

In the past few months I have seen several allowances in the financial art units (3693, 3694) using very similar reasoning. Hopefully we are seeing a way forward.

Gene Quinn

June 30, 2016 11:33 amEd-

I tend to agree with you, but this seems to be what we are left with. A purely subjective test where reasonable minds can obviously differ. That was the death of prior tests for software patent eligibility (think FWA).

For those interested in more on FWA see:

https://ipwatchdog.com/2014/12/02/freeman-walter-abele-a-tortured-history-of-software-eligibility/id=52271/

I should probably revisit that post again after the holiday. I firmly believe the evolution of software patent eligibility places us back to the future with FWA, where the test seemed objective but was purely subjected and allowed the panel (or judge) to do whatever they wanted under the guise of what was supposed to be an objective test.

-Gene

Edward Heller

June 30, 2016 11:11 amPersonally, I think the court was dead wrong in not deciding that the claims passed Alice step one. The court said it was a close call but I do not think it was. The claims were clearly directed to an improvement in computer systems as opposed, to an improvement in business methods. As such, the claims were directed to improved machines and should have passed Alice step one.

Night Writer

June 30, 2016 10:05 amIf not for Chen, we would have nothing. Enfish isn’t that great for software and is more a lame attempt by Hughes at legislating a technology test for the US.