In his recent article in IPWatchdog, Toshio Nakajima lamented that the US automobile industry is beset by patent troll IP Threats so that “automakers can’t fully innovate, grow and prosper.” Nakajima illustrated those threats by first asserting that patent “troll” suits filed against automakers grew to over 100 patent lawsuits in 2014, suits that “often result in six and seven-figure settlements, and represent a serious drain on the automotive industry” (our emphasis). Second, Nakajima referenced Richard Snow’s 2013 Forbes’ magazine article entitled “The Father of All Patent Trolls,” which refers to George Selden and his early automobile patent No. 549,160. Snow writes,

“Patent trolls feed particularly voraciously on technology firms? Apple and Google are currently spending more on patent litigation than on research. The situation is strongly reminiscent of what happened a century ago, when a particularly audacious troller [the Selden patent owner] beset another new technology. The result was a years’ long lawsuit that stifled the infant automotive industry” (our emphasis).

The “troll” narrative of Nakajima and Snow will have us believe that any patent lawsuit to resolve a dispute constitutes abusive litigation. Economic folklore devoid of scale and proportion should not mislead this blog’s readers. First, even if one takes at face value Nakajima’s “six to seven figure” cost for settling per suit, those costs amounted to about $100 million in 2014. This is less than 0.01% of the $1.1 trillion in U.S. automobile sales in 2014, hardly a “serious drain on the automobile industry.” The growth in number of suits may simply be a result of the automotive industry shifting from traditional incremental improvement into adoption of new technologies developed outside that industry such as radar, sensors, navigation, video imaging, smart displays, batteries, electric propulsion, and computer-controlled systems. Second, we have shown that allegations that the Selden patent litigation “stifled the infant automobile industry” are false. We do so in-depth elsewhere by marshalling historical empirical evidence from primary sources in our article The “Overly-broad” Selden patent, Henry Ford and Development in the Early US Automobile Industry.

The litigation was between the Selden patent assignee, the ALAM (Association of Licensed Automobile Manufacturers) and the Ford Motor Company. This case is an excellent illustration of how industry actors such as Henry Ford manage lawsuit “threats” and prosper. This case exemplifies why academic and policymakers’ concern about “uncertainty” over the breadth and validity of patents is often overblown. Those in the industry such as Henry Ford, motivated by the responsibility and potential liabilities of bringing novel products to market, acquire the knowledge necessary to eliminate such uncertainty through an assessment of whether patentee statements about the breadth of their claims are justified. The process of expert assessment is the same today as it was a century ago, whether it occurs in litigation or a private investigation in Freedom to Operate or licensing analyses.

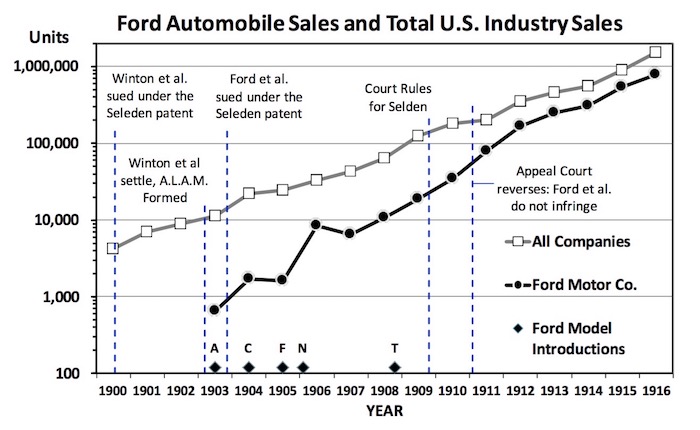

First we synthesise the evidence which shows that the threats of the ALAM never deterred industry entrants and that the rate of productivity and quality improvements in automobile manufacture were never as high as during the term of the Selden patent. As shown by the log scale of unit sales in Figure 1, rather than Ford being “stifled,” the Ford Motor Company grew sales at an exponential rate faster than the total industry during the period of litigation, introducing five new models in as many years, and becoming the leading manufacturer of automobiles produced in 1906, a position the company retained until 1927. A serial developer of five major automobile models, which gained tenfold increase in sales every four years, can hardly be considered to have been “stifled.”

Figure 1. Ford Automobile Sales and Total US Industry Sales, including dates of major Ford model introductions and significant Selden patent litigation events.

We show that starting from 1897 when Henry Ford applied for his first patent (No. 610,040)—six years before the incorporation of the Ford Motor Co.—he understood how to file and prosecute patents, understood the value of patent attorneys and worked closely with them and understood—as shown by his many early development contracts—that patents were essential to attract investors. This was a man skilled in the forefront of his art and with an understanding of the business importance of patent law.

When the ALAM asserted the Selden patent, Ford became acquainted with the legal opinion on the Selden patent from patent attorney Parker. This legal opinion revealed what Selden had actually invented—a road carriage combining known elements with an improved Brayton engine (obsolete in 1903) and that the Patent Office had already rejected Selden’s proposed broader claims during prosecution. From this point Ford understood the future defense against the Selden patent. Ford announced in the trade press that he would ignore the infringement notices and demand letters and would “Contest the Selden patent”.

When the ALAM published a warning that prospective buyers of unlicensed automobiles would be “liable to prosecution for infringement” in the Detroit Free Press on July 26th, 1903, the Ford Motor Co. responded three days later with a public announcement that it would “protect you against any prosecution for alleged infringement of patents.” The financial implications of this offer of indemnity to buyers of automobiles is definitive evidence that the Ford Motor Company was already confident that it understood that a future court adjudication would not sustain the ALAM’s broad construction of the Selden claims.

Parker, the Ford Motor Co. patent attorney, and generally the automobile industry as a whole, have in 1903 correctly appreciated the weakness of Selden’s overbroad claims. They anticipated the 1911 appeal court’s adjudication giving the claims much narrower construction than that asserted by ALAM—rendering the Selden patent commercially irrelevant.

Our analysis of the Ford Motor Co.’s financial statements in its first and most vulnerable year of operation shows that the costs of litigation were trivial—less than 0.9% of automobile sales. The publicity of the litigation served as a form of advertising for the company and for Henry Ford, fetching value that likely exceeded the cost.

Are there occasional outlandish claims by patent litigants? Of course there are, just as in any other area of civil litigation. Have patent assertions of any kind had a real “stifling” effect on development and the rate of new technology introduction in emerging industries? The answer is a resounding NO for every emerging industry we have studied, including early electric lamps, aircraft, radio and automobile industries. The contrary seductive, false narratives, such as those by Snow and Nakajima, belie the real character of innovation, where the cooperative economic surplus of patented technologies dwarfs any costs of managing patent rights and related disputes. The study of the automobile industry’s response to the Selden patent shows what we have seen in other case studies—patent lawsuits are simply a means to bargaining in an uncertain and illiquid market of rights.

Read our full article on SSRN.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

6 comments so far.

Dale B Halling

July 10, 2016 07:00 pmThank you Ron – excellent work

Anon

July 1, 2016 07:35 amThank you Ron. Yes, “non-responsive” is a better adjective (I was trying to be “pleasant” as I was thinking that the Executive Office would not deign to actually partake in this forum (although perhaps Gene may extend an invitation to some key player to add to the discussion here…).

Do you have a link to your IQA appeal?

(and once again thank you for pursuing this – the government may not care – as evidenced by their lack of timeliness – but I am aware of many that do care, and do appreciate your taking the lead to effect some change.

Ron Katznelson

June 30, 2016 10:52 pmAnon @3 – FYI: The agency response was not weak – it was totally non-responsive. IQA appeal filed requesting that the agency provide the reasons for denying all 21 specific requests for correction of the PAE Report. Under the APA, the agency must give reasons for its decision. The 60-day period for agency reply passed with no reply to date. Stay tuned for next steps.

Anon

June 30, 2016 04:14 pmSlightly off topic, but I was wondering what Mr. Katznelson’s next step was in dealing with the rather weak government response to his quest for the Executive Office to clean up the “Tr011” propaganda political paper.

Any updates Ron?

Steve

June 30, 2016 03:20 pmExcellent article and paper — thanks guys.

American Cowboy

June 30, 2016 09:40 amYes, we know the auto industry got stifled, because the buggy whip manufacturers still rule the world! Huzzah!