This summer has truly been a scorcher in many parts of the United States. In the middle of June, residents of southwest California, Arizona and surrounding areas saw temperatures creep towards 120°F, breaking records which had been set 50 years earlier in some places. Parts of the Great Plains, including Kansas and Colorado, saw temperatures exceeding 100°F during the same period of time. Heat exposure claimed five lives in Arizona during the heatwave, many of them hikers who had run out of water during their trek.

For many people, escaping the heat is as simple as getting indoors and flipping the switch that turns on the air conditioner, sending cool air into any room. Statistics released in August 2011 by the U.S. Energy Information Administration indicates that 100 million homes in the U.S.., about 87 percent of all American households, had at least one air conditioner. According to the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), air conditioners use five percent of all electricity produced in America at a total cost to homeowners of more than $11 billion.

Bringing us to this modern air of indoor climate control is a famed innovator and a 1985 inductee to the National Inventor’s Hall of Fame: Willis Haviland Carrier. Although he wasn’t the first person in history to conceive of a system for conditioning air within a confined space, his engineering solutions at the turn of the 20th century solved a problem in industrial processes that would go on to revolutionize the way that ordinary people are able to beat the heat during the long summer months.

[Varsity-1]

An Early History of Air Conditioning

From 2nd Century China to Benjamin Franklin

Reports of the first air conditioning system known to man stem back to the 2nd century and the Chinese Han dynasty. An inventor known by the name Ding Huan is believed to crafted an evaporative cooling system, although some reports believe that this is a mistaken attribution. In any event, Huan is likely to have crafted a type of multi-tiered hill censer, a device used during the Han dynasty to burn incense, which used convection currents to rotate a device surrounding the censer, creating an animated effect. It may not have been used to cool a room but it is an early example of the use of hot air convection in engineering to transfer heat.

Perhaps the earliest example of air conditioning in the modern world involves one of the great American statesmen from the days of the Founding Fathers, Benjamin Franklin. Franklin was well-known for his overseas travels and one visit to the University of Cambridge in 1758 brought him into contact with Dr. John Hadley, a professor of chemistry. Franklin was in conversation with Hadley on the cooling properties of evaporation. Hadley proposed that he and Franklin conduct experiments on a thermometer to see how the evaporation of ether from the thermometer’s ball reduced its temperature down to 7°C. The pair even witnessed the formation of ice on the thermometer with repeated evaporations. These experiments are found written down in a letter from Franklin to John Lining, an early American medical scientist.

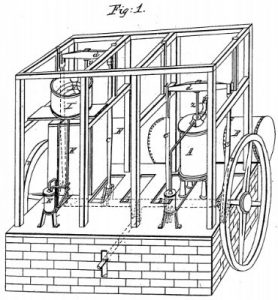

Another early name on the path towards the discovery of air conditioning is Dr. John Gorrie, a physician working in Florida who believed he had come up with a novel treatment for yellow fever. Multiple accounts of Gorrie’s story mentions a note he makes in which he draws the conclusion that cold air would help his patients: “Nature would terminate the fevers by changing the seasons.” Through the 1840s, Gorrie worked on an apparatus that would compress air, raising the air’s temperature, and then force that air through coils submerged in a cool water bath. When the air returned to its normal pressure, its temperature would further reduce and the air would be exhausted into a room for conditioning the air. Gorrie would receive a patent for his device: U.S. Patent No. 8080, entitled Ice Machine and issued in May 1851. Gorrie attempted to market his device but his chief financial backer died in the same year that he obtained his patent and he had problems competing thereafter.

Another early name on the path towards the discovery of air conditioning is Dr. John Gorrie, a physician working in Florida who believed he had come up with a novel treatment for yellow fever. Multiple accounts of Gorrie’s story mentions a note he makes in which he draws the conclusion that cold air would help his patients: “Nature would terminate the fevers by changing the seasons.” Through the 1840s, Gorrie worked on an apparatus that would compress air, raising the air’s temperature, and then force that air through coils submerged in a cool water bath. When the air returned to its normal pressure, its temperature would further reduce and the air would be exhausted into a room for conditioning the air. Gorrie would receive a patent for his device: U.S. Patent No. 8080, entitled Ice Machine and issued in May 1851. Gorrie attempted to market his device but his chief financial backer died in the same year that he obtained his patent and he had problems competing thereafter.

Willis Carrier Uses Fog to Solve a Printing Problem

Willis Haviland Carrier was born on November 26th, 1876, in Angola, NY, a small village about 25 miles south of the city of Buffalo which touches the shores of Lake Erie, providing residents with plenty of beachfront and glorious sunsets. In 1901, he earned an engineering degree from Cornell University and began working at Buffalo Forge Company that same year.

In 1902, shortly after joining Buffalo Forge, Carrier had a momentary insight while standing on a train station in Pittsburgh, which would lead him to develop his first air conditioner system. The oft-repeated story of this discovery involves something of a paradox: Carrier, surrounded by fog, realized that he could dry air by adding water to warm, humid air to create fog. He realized that if he saturated the air with water, he could control the temperature of that saturated air by passing it through a cool water spray that caused the moisture of hot, humid air to condense and leave the air stream. Although the cooling of air had been demonstrated by Gorrie, Franklin and others, Carrier solved the problem of removing humidity from the air.

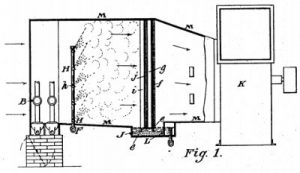

Carrier and Buffalo Forge applied for a patent for Carrier’s humidity treatment system and on January 2nd, 1906, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office issued U.S. Patent No. 808897, entitled Apparatus for Treating Air. It claimed an air-purifying apparatus including both an air-conduit and a separator with a series of upright plates having oblique faces forming a continuous surface lengthwise of the conduit. The front portion of that surface was unobstructed so as to let liquid distribute along the plate faces. Succeeding portions of the surface included projections obstructing the flow of liquid along the conduit’s length to promote the separation of liquid from air. The patent states that the main objective of the invention is to remove solid impurities and other “noxious material” from the air in such a way that could alter the air’s temperature and humidity.

Carrier and Buffalo Forge applied for a patent for Carrier’s humidity treatment system and on January 2nd, 1906, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office issued U.S. Patent No. 808897, entitled Apparatus for Treating Air. It claimed an air-purifying apparatus including both an air-conduit and a separator with a series of upright plates having oblique faces forming a continuous surface lengthwise of the conduit. The front portion of that surface was unobstructed so as to let liquid distribute along the plate faces. Succeeding portions of the surface included projections obstructing the flow of liquid along the conduit’s length to promote the separation of liquid from air. The patent states that the main objective of the invention is to remove solid impurities and other “noxious material” from the air in such a way that could alter the air’s temperature and humidity.

Carrier found the first industrial application of his technological breakthrough in a Brooklyn firm known as Sackett & Wilhelms Lithography and Printing Company. This company was experiencing an issue in its printing processes wherein humidity would cause paper to expand and contract. Because color ink was applied one color at a time, a misalignment in the printing process would occur, reducing the quality of prints made on humid days. Carrier penned a set of blueprints he initialed on July 17th, 1902, for a series of coils, fans, ducts, heaters and perforated steam pipes which was designed to maintain a constant humidity of 55 percent.

Carrier’s discovery of air conditioning improved his professional prospects almost immediately. By 1905, he was made head of Buffalo Forge’s engineering department. In following years, his air conditioning systems were implemented in plants producing pharmaceuticals and silk for control over both temperature and humidity in production processes. Carrier received great renown in 1911 when he presented his Rational Psychrometric Formulae to the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME). His presentation at the 1911 ASME meeting essentially launched air conditioning as a reputable field of engineering.

World War I had a major effect on Carrier’s fortunes and serves as a good reminder that, sometimes, crisis and opportunity are the exact same things. In 1914, Buffalo Forge decided to dissolve the Carrier Air Conditioning subsidiary which it had established based on Willis’s invention. The following June, Willis Carrier along with the help of J. Irvine Lyle, previously Buffalo Forge’s Manhattan sales head which had presented the Sacketts & Wilhelm problem to Carrier, and five colleagues founded Carrier Engineering Corporation with a combined capital of $32,600. The war which had ended Carrier’s prospects at Buffalo Forge reportedly led to 10 of his first 29 contracts, fuse producing companies whose products were used by the Allies.

In 1922, Carrier would introduce the centrifugal refrigeration machine which enabled small-scale air conditioning instead of the energy-intensive industrial level of cooling previously practiced by the company. This configuration allowed for the conditioning of air in public places and Carrier gained wide acclaim for installing these systems in a series of theaters throughout the 1920s. These would include Sid Grauman’s Metropolitan Theatre in Los Angeles, Dallas’s Palace Theatre and the Rivoli Theatre in New York City.

The air conditioning industry, and Carrier’s business, would continue to expand through the 20th century, surviving the passing of Willis Carrier on October 7th, 1950. Even though environmental concerns over the use of certain refrigerants have increased over time, the western migration of Americans over the past century have provided ample demand for air conditioning services in hot, arid regions of the country. The Carrier name continues to live on as a branded subsidiary of United Technologies Corporation (NYSE:UTX), a developer of aerospace and building systems.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

3 comments so far.

Night Writer

July 14, 2016 06:49 amRead the claims of these patents and compare with Mark Lemley’s unethical functional vanity press publication.

Night Writer

July 13, 2016 04:52 pmI love these articles too. The claims are pretty cool at the end of the patents. Note that they are not a very low level of specificity as Lemley has unethically contended in this functional claiming paper. I challenge Lemley. He is unethical and I can prove it. The SCOTUS should strike from its record any reference to his judicial activist papers with poor citing and outright lies.

Steve

July 13, 2016 11:30 amThanks Steve. Love these articles on past inventors.

Interesting. Inspiring. Encouraging.

American ingenuity at its best.