During 2015, total U.S. consumer spending for the home entertainment industry was $18 billion, an increase of 1 percent over 2014’s totals. This total includes sales of DVDs and Blu-ray discs along with subscription revenues for video on-demand (VOD) services. Although sales of DVDs and Blu-ray have been declining in recent years, unit sales for both eclipsed 25 million through the first eight months of 2015. VOD subscriptions, meanwhile, have grown to amazing heights in the United States. Media consumption research firm Nielsen reported this June that subscription VOD penetration rates have reached 50 percent of U.S. households, equaling the penetration rate of DVR.

During 2015, total U.S. consumer spending for the home entertainment industry was $18 billion, an increase of 1 percent over 2014’s totals. This total includes sales of DVDs and Blu-ray discs along with subscription revenues for video on-demand (VOD) services. Although sales of DVDs and Blu-ray have been declining in recent years, unit sales for both eclipsed 25 million through the first eight months of 2015. VOD subscriptions, meanwhile, have grown to amazing heights in the United States. Media consumption research firm Nielsen reported this June that subscription VOD penetration rates have reached 50 percent of U.S. households, equaling the penetration rate of DVR.

As video technologies move forward into an age where more viewers watch movies through an online app, the traditional trappings of physical media for video continue to fall away. This July marks a huge milestone along this trajectory. Reports from Japanese media indicate that Osaka-based Funai Electric (TYO:6839) will cease production of videocassette recorders (VCRs) by the end of the month. The company cited a few issues such as a difficulty to source parts and dwindling sales which dropped to 750,000 units in 2015; at its peak, Funai was selling 15 million VCR units per year.

The death knell for videotape technologies has been sounding for some time. Last year, Tokyo-based electronics conglomerate Sony Corp. (NYSE:SNE) announced its decision to discontinue both Betamax videocassettes and Micro MV cassettes used for recording. The Video Home System (VHS) standard suffered a significant blow in 2008 when the last major VHS distributor discontinued sales. Although few are bemoaning the loss of videotape thanks to the convenience and higher quality of discs and VOD, production of the world’s last VCR turns our focus backwards in time to see the rise and fall of this early home video technology.

Charles Ginsburg and the Early Days of Videotape

Prior to 1951, home entertainment largely revolved around the broadcast schedule for radio and television, the latter of which was still very much in its infancy. The 20th century saw the advent of consumer broadcast technologies but for the most part American consumers were beholden to the entertainment schedule offered by four stations: CBS, NBC, ABC and DMN, the long-defunct DuMont Television Network. Likewise, these broadcast companies were forced to produce live content as there was no way to record programs for later playback.

The road towards consumer choice in watching recorded video at their convenience was started by American engineer Charles Ginsburg, a 1990 inductee into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. Born July 27th, 1920, Ginsburg’s educational career included medical studies, genetics and animal husbandry before finding work as a sound technician in San Jose. In 1952, Ginsburg was recruited to join Ampex Corporation which at that time was focused on research and development efforts on creating a magnetic videotape recorder. Videotape recordings had been demonstrated as early as November 1951 but early systems suffered from blurry images which provided indistinct scenes.

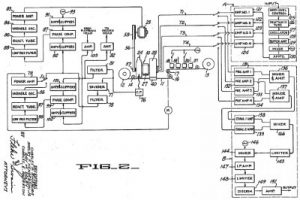

Early video recorders used audio tape which was pushed past recording heads at speeds up to 240 inches per second in an attempt to create the higher frequencies required for video recording. Ginsburg was able to reduce the speed at which the tape traveled by increasing the speed of the recording head to achieve those high frequencies. This innovation is reflected in U.S. Patent No. 2956114, titled Broad Band Magnetic Tape System and Method. It protected a method of recording a frequency spectrum in a recording system by frequency modulating a carrier frequency so that the carrier frequency’s maximum deviation is less than the maximum frequency of the frequency spectrum and then recording the frequency modulated carrier. The method produced good results for recording and reproducing television without resulting in signal variations during recording.

Early video recorders used audio tape which was pushed past recording heads at speeds up to 240 inches per second in an attempt to create the higher frequencies required for video recording. Ginsburg was able to reduce the speed at which the tape traveled by increasing the speed of the recording head to achieve those high frequencies. This innovation is reflected in U.S. Patent No. 2956114, titled Broad Band Magnetic Tape System and Method. It protected a method of recording a frequency spectrum in a recording system by frequency modulating a carrier frequency so that the carrier frequency’s maximum deviation is less than the maximum frequency of the frequency spectrum and then recording the frequency modulated carrier. The method produced good results for recording and reproducing television without resulting in signal variations during recording.

Ginsburg’s innovation was first marketed in 1956 as the Ampex VRX-1000 at a price of $50,000 per unit; CBS was the first company to employ the technology. Before long, cable companies were moving away from live broadcasts and towards recordings that could be replayed at prime time hours for viewers from coast to coast. Later, the helical scan system would improve video recording by wrapping film around a recording drum at an angle, further reducing tape speed while improving the ability to record video at high frequencies.

Sony and JVC Face Off in the Videotape Format Wars

Of course, American families couldn’t afford Ampex’s high price point and it would take more than a decade for mass consumer options to enter the market. Sony released the world’s first VCR in 1971 based on the U-matic technology it had developed. U-matic introduced the concept of videotape housed within a videocassette instead of a reel format.

What helped Sony take an early lead in the mass market for VCRs and videotape recordings was the tape format famously known as Betamax, released in 1975. Betamax tapes and machines were sold along with the concept of time-shift viewing, allowing consumers to record a program and watch it later at their convenience. Those with a knowledge of historic legal challenges to copyright will likely remember Sony Corporation of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc., a case in which the U.S. Supreme Court decided 5-4 that Sony’s sale of Betamax did not constitute copyright infringement. This case also features one of the more interesting pieces of mental gymnastics in U.S. legal history in which Jack Valenti, then the president of the Motion Picture Association of America, stated that “the VCR is to the American film producer and the American public as the Boston Strangler is to the woman home alone.”

Sony soon found competition in the American market within the borders of its own home country when Japan’s JVC (TYO:6632) released its VHS system in 1976. VHS cassettes used technology which was similar to Betamax but there were a few important differences, the most important of which was VHS’s longer playback. Even though Sony had achieved a dominant market position through Betamax, consumers and the movie industry alike turned to VHS because those videocassettes could contain a full-length movie.

The videotape format wars between Sony and JVC would extend into the 1980s, but the eventual winner was clear. Today, when one thinks of a videocassette, that person will typically envision the thinner rectangular cassette with two transparent panels on either side for viewing the film reel, the iconic look of the VHS.

The Rise of Blockbuster and the Onslaught of DVDs

Fortunately for Jack Valenti, videotape wasn’t the killer which he had envisioned. In fact, movie production studios experienced a great boon in video rental sales of movies. In 1986, Waldenbooks, at that time the nation’s largest bookseller, forecast an 80 percent increase in home video revenue for that year. Interestingly, the Billboard issue which that tidbit comes from lists Walt Disney Home Video as the producer of eight of the top 10 selling children’s video producers; Disney was a party in the Sony v. Universal City Studios case.

The company which is perhaps most closely associated with the rise and fall of home video is Blockbuster, the now-defunct video rental chain which was founded in 1985. Blockbuster became successful by offering a wide variety of titles shelved across a wide floor space which gave consumers the ability to browse entire genres. By 2004, Blockbuster had reached a market value of $5 billion with $5.9 billion in annual revenue coming from 9,000 stores across the world.

But well before 2004, the DVD format had been established by a consortium of ten tech companies which included both Sony and JVC, bringing those former warring factions under the same aegis. There were certainly those who questioned the merits of the DVD format versus tape-based VHS but the DVD offered better data versatility. Interactive features and the ability to skip to any scene within a movie without having to fast-forward or rewind became prized by consumers. By January 2002, the DVD Entertainment Group was reporting that DVD players were in one out of every four U.S. homes and that DVD sales had finally overtaken VHS sales. At that point, there was a clear downward trajectory for video leading to the recent news of the last VCR unit to be commercially produced.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[[Advertisement]]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-banner-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-938x313-1.jpeg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

3 comments so far.

Paul Cole

August 1, 2016 08:11 amI can remember when VCRs were launched!

Gene Quinn

July 30, 2016 11:43 amAnon-

I can understand not getting excited, or nostalgic, over the last VCR. It is an interesting cautionary tale, however, for tech companies (well all know who they are) who seem to think that what they have right now will last forever. The one thing we know about technology is that there is always going to be something that comes next. Sometimes that which comes next supplants what up until then was perfectly fine and dominated the industry.

-Gene

Anon

July 30, 2016 11:29 amThe last Beta…

The last 8-Track…

The last Vinyl record…

The last “wax-tube”…

(pardon me for not getting too excited) 😉