The application of the Supreme Court’s decision in Alice v. CLS Bank by the Federal Circuit has been disappointing, to say the least. There have been some rays of hope for innovators with decisions in DDR Holdings, Enfish and BASCOM, but these bright spots shine so radiantly because they are scattered in a sea of despair. Whether the Supreme Court intended to kill software patents or not, the way the Federal Circuit, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) and many patent examiners have applied Alice is to render much software patent ineligible in the United States.

The application of the Supreme Court’s decision in Alice v. CLS Bank by the Federal Circuit has been disappointing, to say the least. There have been some rays of hope for innovators with decisions in DDR Holdings, Enfish and BASCOM, but these bright spots shine so radiantly because they are scattered in a sea of despair. Whether the Supreme Court intended to kill software patents or not, the way the Federal Circuit, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) and many patent examiners have applied Alice is to render much software patent ineligible in the United States.

One particularly disconcerting and largely unpredictable aspect of Alice is how it has been used to render games patent ineligible.

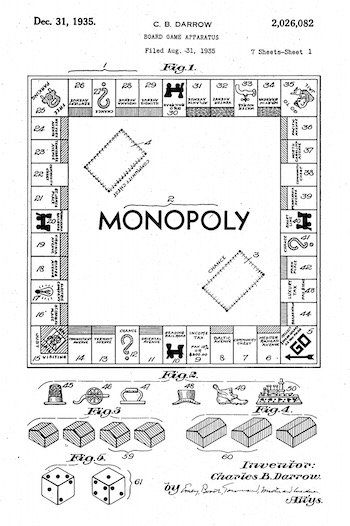

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has long issued patents for new games using conventional equipment (e.g., balls, clubs, cards, etc.) where the invention lies in the steps of the game. For example, in 1935 the USPTO issued U.S. Patent No. 2,026,082 on Monopoly®, and the USPTO has had gaming art units and classifications for decades. For example, see Art Units 3711 and 3714, and classes 273, 463 and 473.

Given the way Alice is being interpreted by both patent examiners and some of the judges on the Federal Circuit, one has to ask whether games are patent eligible any more. Could Monopoly® be patented if it were newly invented in 2016? According to at least some judges on the Federal Circuit, rules of game play are abstract ideas. But how can something that is defined with enough specificity to allow average citizens to enjoy countless hours of enjoyment be abstract? What exactly is abstract about a game, or the rules of a game? Absolutely nothing, and that this isn’t self evident speaks volumes of just how far we have fallen down the rabbit hole in the pursuit of whatever it is the Courts are presently chasing.

Monopoly® is not the only successfully patented game, although it quite possibly is the most famous patented game. Still, in the field of card games, the USPTO has long issued patents for entirely new games, improvements to existing games, and new betting options and/or payouts for existing games, all using conventional playing cards. See, e.g., U.S. Patent No. 5,823,873 (improved poker game using conventional cards commercialized as Triple Play Draw Poker®); U.S. Patent No. 5,154,429 (method of modified blackjack using conventional cards). There have also been many success stories of inventors commercializing or licensing patented new games.

In re Smith

Notwithstanding, earlier this year, in March 2016, the Federal Circuit issued a curious and highly questionable decision in In re Smith, which incorrectly expands the “abstract idea” test of Alice well beyond where the test was ever envisioned going. The panel decision extended the Alice reach to claims directed to performing a novel and non-obvious underlying practice that did not previously exist (steps of a new game) with known manufactures (cards).

The ruling in In re Smith is wrong because a process that did not previously exist simply cannot qualify as an “abstract idea” under step one of the Alice test. Furthermore, although we have not been told the definition of what it means to be “abstract” or for an idea to be an “abstract idea,” whatever those terms mean the logically cannot said to apply to a novel and non-obvious process. Indeed, a process that has never before existed, and which is thoroughly described, must logically transform an otherwise “abstract idea” into eligible subject matter under step two of the Alice test.

Under the statute, new processes that use conventional equipment or materials are clearly patent eligible subject matter. See 35 U.S.C. § 100(b), which says that patent eligible processes include “a new use of a known process, machine, manufacture, composition of matter, or material.” (emphasis added). The Supreme Court has never abrogated § 100(b), so it should be applied rather than ignored as if it doesn’t exist.

With respect to the game at issue in In re Smith, it was undisputed that the claimed combination of game steps is new, as the USPTO found that the Applicant overcame all §102 and §103 rejections based on the recited combination of such steps.

To fail the first step of the Alice test, a claim needs to tie up an “abstract idea,” which for purposes of this test was defined to be a preexisting practice that serves as a fundamental “building block of human ingenuity,” such as a “longstanding” and “prevalent” economic practice. Alice, 134 S. Ct. at 2354, 2356. In conflict with the statute and the Supreme Court’s reasoning, the Federal Circuit panel in In re Smith applied the Alice test to claims that indisputably recite a new set of game steps that was not preexisting, let alone “fundamental.” The inventiveness of the claims was based on the previously unknown combination of game steps, not the cards.

Left uncorrected, the panel’s decision will be applied by patent examiners, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), and district courts to create an improper categorical ban against patents claiming new games or similar inventive practices using conventional equipment. Such a categorical ban is contrary to the statute, controlling precedent and the USPTO’s own long history of granting patents on inventive practices using known equipment, including numerous game patents.

Alice-creep

This type of Alice-creep is particularly disconcerting because it ignores the primary concern of the Supreme Court in Mayo. Much of the 101 patent eligibility mischief we now experience can be traced back directly to Mayo v. Prometheus, where the Supreme Court ruled that conventional steps are not enough to transform a law of nature into a patent eligible process. While that decision itself clearly violates the statute, as well as directly overrules Diamond v. Diehr, the concern of the Supreme Court was undeniably and explicitly the additional of conventional steps.

In this case the USPTO found the claimed combination of gaming steps was not preexisting. Indeed, the patent examiner rejected the claims as being abstract because they were “an attempt to claim a new set of rules for playing a card game.” If the claims were a new set of rules that means the steps could not possibly be conventional. If the steps were not convention then Mayo shouldn’t apply at all. Given that the Alice framework is really the Mayo framework applied to abstract ideas instead of laws of nature, why should Alice ever be used to deal with a process that a patent examiner acknowledges is new, non-obvious and appropriately described? It would seem that Alice simply has no relevance in such a circumstance.

Indeed, it is difficult to understand how something that is described with enough specificity to satisfy 35 U.S.C. 112, which is also new and non-obvious, could ever be considered abstract by anyone at all concerning themselves with logic. Of course, such an irrational conclusion can be achieved because the Supreme Court and Federal Circuit have so far stubbornly refused to define the term “abstract idea.”

How can you have a legal test that is applied to refuse property rights to applicants and to strip property rights from property owners where the critical term is intentionally left amorphous and undefined so no one can understand what it means? Not defining the term “abstract idea” and yet applying it in the patent eligibility context goes against everything the law is supposed to stand for: certainty, predictability and fairness. By not defining the term “abstract idea” each decision maker is left to his or her own devices to subjectively determine what is and what is not abstract. Equal application of the law be damned, the Supreme Court and Federal Circuit demand a subjective test that cannot be predictably reproduced by any two people or panels.

It is well past time to acknowledge what every sane person knows, and actually define the term “abstract” so the law has meaning and those subject to the whimsical fancy of the current system can be spared. It is time for the innovators and the rest of the patent community to be informed as to the standards that will be applied. Making it up as you go along might have been funny for a while, but this absurdity is long past being ridiculous; it is problem of fundamental fairness.

Allow me to state the obvious, and what the Supreme Court and Federal Circuit seem afraid to acknowledge. The term “abstract” is defined as “being apart from concrete realities, specific objects, or actual instances.” Defining the term “abstract” in this common sense, everyday way, makes it is easy to understand that when an application has specifically defined the invention with enough specificity to satisfy 35 U.S.C. 112 the claimed invention cannot possibly be abstract.

And for goodness sake, if you have enough information to evaluate whether what is being claimed is novel and non-obvious how in the name of common sense can you with a straight face say what is being claimed is abstract? If it was abstract then you couldn’t possibly have conducted a novelty analysis or obviousness inquiry because the rights being sought would have been too bloody amorphous to allow for the type of careful scrutiny that is supposed to be applied when conducting a review of prior art under §102 and §103.

What about Monopoly®?

It seems clear that with the right Federal Circuit panel (or wrong panel depending upon your viewpoint) Monopoly® would be patent ineligible because it is nothing more than an abstract idea.

I find it impossible to believe that the Supreme Court intended Alice to rewrite generations of patent law applicable to the patentability of games, which simply were not at issue in Alice. Whether anyone likes it or not, the Supreme Court has only ever had the chance to rule on rather straight forward financial services business method patents in its modern “software” cases. To apply Alice to reach truly illogical results outside of the financial services business method patent space is wholly inappropriate. Hopefully the Federal Circuit will wake up and realize that applying Alice to wholly different facts patterns is extraordinarily inappropriate and akin to a first year law student over extrapolating to the point of absurdity.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

44 comments so far.

Prizzi’s Glory

September 1, 2016 04:43 pmIt is possible that the corpus of case law has rendered the patent system logically inconsistent.

The Monopoly game board, which was considered patent-eligible, is a simple model of a market in property.

One could formulate the previous statement as follows.

The Monopoly game board is a physical structure that maps bijectively into a simple model of a market in property.

In re Lowry tells us that data structures are patentable.

The Monopoly rules describe a system of investing by multiple market investors and will eventually converge to a winner (game theory says so).

The rules provide limitations on the claimed board game apparatus claimed on the monopoly board. (See Monopoly claim 9.)

The Alice claims could have been formulated in terms of a structure/model/board representing the market, an apparatus representing the participation of competing investors in the market, and rules that enable some subset of the investors to profit (i.e., win).

If we think of Alice in this way, then the problem with the Alice claims is not abstract ideas but simply indefiniteness.

Of course, if there is no way to formulate the Alice claims in a SCOTUS-acceptable fashion, then all game claims really must be 101-ineligible.

In other words, one can argue from the Supreme Courts Alice logic that hedging and hedging-like methods are never patent-eligible while one can argue from the historical allowance of claims involving rules applied to a game apparatus claimed from a game board/structure/model that hedging and hedging-like methods can certainly be formulated in a way that is patent-eligible.

Yet a game board seems inherently a structure that is patent-eligible.

SCOTUS seems to argue in Alice that adding limitations to a patent-eligible structure creates a less general claim that is patent-ineligible as an Abstract Idea.

That train of logic makes no sense whatsoever to me.

Can anyone tell me where my reasoning is flawed?

(M)

August 25, 2016 10:22 pmI’m looking forward to winning my case before the Supreme Court if it comes to that. (My game mechanics are that novel and that good, and I’m being modest.) From a game designer’s perspective, the Smith’s claims were weak tea. I’m not shocked they got knocked down, and I’m undaunted.

(Plus, if all else fails, we’ll always have Spry Fox vs Lolapps. 😉

Anon

August 22, 2016 07:55 pmYKWIA @ 40,

You ask a bunch of questions which shows that your final statement simply is not what you think it to mean.

Let me reply to your replies:

To the need to appreciate what “utility” means in the context of patent law, this should be self evident. The term has a distinctive meaning in patent law and your unwillingness to even recognize that with your attempts at humor(?) show exactly why you need to appreciate the legal meaning.

Still my point.

To the need to disabuse yourself from the “software is like a literary work,” mantra, the answer as well lies with the need to understand the law. Clearly you understand neither patent law nor copyright law, and your question of “Why? in the face of my direct answer shows that you are unwilling to learn the correct answer. If you have an issue with not being able to separate function from expression, you should know that you cannot obtain a copyright on such an item.

Still my point.

To the understanding of the legal term of equivalence, and your reply that you know what it means, your further comment evidences that you do NOT know what it means. You attempting to fold in copyright on this purely patent law aspect only seals the deal.

Still my point.

To your reply invoking State Street, when I was talking about Alappat, you have not answered my point.

Still my point.

To your reply that “every patent system is bedeviled” to my point that your example of the international standard misses the mark, your reply itself ALSO misses the mark. This only shows that you are fixated on your own philosophical viewpoint to the exclusion of what the law actually is.

Still my point.

To your reply of not limiting yourself to software, you have not addressed my point that software is NOT information.

Still my point.

To your off-point replies of other items in response to my point that software is only created to be used in conjunction with a machine and is thus a machine component, your attempt to move the goal posts fails. You need to not use other things as I am not talking about other things.

Still my point.

And to reiterate, your words of “ Handily, the words on the page stand for themselves.” are very much true – but certainly not in the manner in which you would like.

Gene Quinn

August 22, 2016 02:21 pmYou Know Who I Am-

This forum is for those who are seriously interested in having a factually correct discussion of the issues. If you are incapable of having such a discussion please go elsewhere. Opinion is one thing, but factual inaccuracies are not acceptable.

First, despite what you have said, State Street has been explicitly overruled. Please read Bilski v. Kappos to inform yourself.

Second, Alappat have not been overruled and remains good law.

Third, software is not a literary work and the writing of code is, of course, separable from the utility provided by the code written.

Fourth, copyright law protects against copying and pasting and as such is not a useful or appropriate form of protection for software. You might as well obtain a copyright, but you get the $30 worth of protection the application costs.

-Gene

You Know Who I Am

August 22, 2016 01:32 pm“You need to appreciate what “utility” means under patent law”.

Why? I know there are useful things that cannot be patented. A sound legal argument, for example, could be most useful, but may not be patented. A better recipe for salsa is mighty useful, but not patent eligible.

“You need to disabuse yourself of the “software is like a literary work” mantra (software does have aspects of expression that do garner copyright protection, but also has aspects of functionality that do garner patent protection)”.

Why? There is clearly tension in both copyright law and patent law in separating expression from function. The structure, sequence and organization of a software work is sometimes inseparable from its utility. If software produces information consumed by people, and you need IP protection, copyright would be the proper vehicle, since copyright is concerned with the human consumption of protected works.

“You need to understand what equivalence means in the patent law arena (and not attempt to become sidetracked with a poster’s shortcut of “=”)”

I know what it means. I know it is in direct tension with copyright, where the question of how close a copy is too close is often the central inquiry.

“You need to understand that inventions often can be claimed in multiple statutory categories”.

I do understand this as well- and if you can get a machine or composition of matter or manufacture status, fantastic; my proposed doctrine won’t apply. Good luck getting one of those with a typical software invention.

“You need to understand that Alappat is NOT “dead dead dead.”

No, you need to understand that it is. Nobody ever overturned State Street either, but it’s dead too.

“You need to understand that your example of the international standard does NOT carry the logical nor legal weight that you think that it does. This is tied to you need to understand that software has multiple aspects that are afforded DIFFERENT protections under different IP laws.”

You need to understand that every patent system is bedeviled by the information invention problem.

You need to understand that your “focus on information” has become obfuscated when you attempt to aim at software, as software is not information”.

I am not limiting my doctrine to software – only claims to methods that result in information- which software assuredly produces. I say so multiple times.

“Since you claim to be knowledgeable of the software industry, you should be aware that ALL software is created to be utilized in conjunction with a machine: software is a machine component”.

Is a television broadcast a component of a television? Is the pattern fed to a weaving loom a machine component?

“And lastly, your view of what a reasonable legal person would view as to being on the short end is simply Unreasonable”.

Uh huh. Handily, the words on the page stand for themselves.

Anon

August 18, 2016 07:41 pmWhat Ever Name You Want to Go By @34,

Your moniker does not matter – but your understanding of patent law – or more correctly, your misunderstanding – does matter.

You need to appreciate what “utility” means under patent law.

You need to disabuse yourself of the “software is like a literary work” mantra (software does have aspects of expression that do garner copyright protection, but also has aspects of functionality that do garner patent protection).

You need to understand what equivalence means in the patent law arena (and not attempt to become sidetracked with a poster’s shortcut of “=”).

You need to understand that inventions often can be claimed in multiple statutory categories.

You need to understand that Alappat is NOT “dead dead dead.”

You need to understand that your example of the international standard does NOT carry the logical nor legal weight that you think that it does. This is tied to you need to understand that software has multiple aspects that are afforded DIFFERENT protections under different IP laws.

You need to understand that your “focus on information” has become obfuscated when you attempt to aim at software, as software is not information.

Since you claim to be knowledgeable of the software industry, you should be aware that ALL software is created to be utilized in conjunction with a machine: software is a machine component.

And lastly, your view of what a reasonable legal person would view as to being on the short end is simply UNreasonable.

None of this is new to you.

Yet, you insist on persisting in your ignorance.

step back

August 18, 2016 04:23 pm@37 HWHASWMBO,

Transfer won’t help you.

Alice is everywhere. Even in non-3600 units.

After Alice, nothing is patentable, not even new methods for doctors to clean their hands prior to open brain surgery.

Besides, getting a switch to a new examiner is next to impossible.

–Him who has been there and tried that to no avail 🙂

He who has a she who must be obeyed

August 18, 2016 02:32 pmAs a side note, I am in the process of experiencing close up the heaping pile that is art unit 3600 when it comes to Alice. I have to laugh somewhat at the naiveté of You Know Who I Am when I look at my claims, which are directed to specific (not generic) components within different communication devices and their physical interactions. The examiner indicated that neither she, nor her supervisor, had any technical knowledge of the electronics, and that the application was misclassified, but hey. In addition to adding material to what should not have been close to an Alice claim, the primary won’t go forward unless we specify the data passed between the devices (otherwise, apparently, the method claims are merely algorithmic). The best I can hope for is that the client springs for a CON and we can get it classified into the appropriate art unit (2400/2600).

Glug.

step back

August 18, 2016 01:21 pm@34 Don’t Really Know Who You Are

Process of doctor washing hands is not statutory subject matter?

Let’s step back here if you Mr. Unknown don’t mind.

35 USC 101 clearly deems a useful process to be statutory subject matter.

Even you admit that the process transforms by making the doctor’s hand more hygienic.

The only question left is whether it is novel (under 102) or obvious (under 103).

So let’s say the liquid used for washing is infused with some sort of improved chemical agent that makes the washing even more rigorous, or cost effective, or whatever. Then it’s novel and nonobvious.

And yet you insist is is not “eligible”?

We think we now know who you are.

MM? agent 6? Justice Thomas? King Tut’s Abacus Man?

All of the above?

Curious

August 18, 2016 09:53 amMaybe you aren’t aware that Ux, or User Experience, is in many cases is the preeminent competitive factor in the success or failure of a software product.

The same thing can be said about automobiles, hand drills, snow blowers, and a host of other mechanical devices.

Boy, that don’t sound much like mere computer parts to this country bumpkin.

?? Your definition refers to “occur before, during and after use.” Use is function.

but no reasonable legal observer would think I’m on the short end of the discussion thus far on this thread

LOL … you are not normal. Delusional, probably, but definitely not normal.

Humans using information is the height of abstraction.

I don’t think you understand what is really meant by “abstraction.”

Software is very much akin to a novel, or short story

LOL … delusional and a comedian. I see you didn’t comment on my comparison of the course work of an electrical engineer major, computer science major, and English literature major.

If you claim an item of hardware as a method- but why would you

Hardware is almost always “used.” While some hardware just sits there, most of the time is actively used and that active use can be claimed as part of a method. You couldn’t figure this out?

The idea of a different computer program creating a different machine is dead, dead, dead at the CAFC and the USSC

Dead? Where is the case that overturns Alappat? Your point is a non sequitur — new machines can still be directed to abstract ideas pursuant to Alice/Mayo.

not methods whose sole result is an item of information, wherein the economic value of the information arises from human use of that information

Can you show me where Congress prohibited patents on that subject matter? Congress is the voice of the people — they get to write the law. Your little diatribe turns a blind eye to the fact that the whole “abstract idea” jurisprudence is a blatant power grab by the judiciary to declare what class of inventions should be patentable-eligible or not. It is NOT their job to do so. Their job is to interpret the law. While judges can gap fill, there are no gaps to fill in 35 USC 101.

You Know Who I Am

August 17, 2016 11:50 pmStep Back @ 19, If you read the paper or the text of my comment, you would clearly see that reality-revealing “informational” inventions (e.g. a new microscope, telescope, radio receiver, chemical detector, medical condition detector, etc.) should be patentable (!) because those inventions are a) not methods and b) not methods whose sole result is an item of information, wherein the economic value of the information arises from human use of that information. Human use of information is pure abstraction. I’d like my doctor to know that washing his hands kills germs, but I don’t think that knowledge should be patent-eligible.

Curious@17, if software were hardware, why use two different words? In any case, let’s stipulate that hardware equals software.

If you claim an item of hardware as a method- but why would you- and the method results in information consumed by people, the invention should not be eligible.

If the hardware is new, non-obvious, fully described and distinguishable from the prior art by something other than the character of the information being processed by the hardware, it would be a new machine or composition of matter and claimed as such.

The idea of a different computer program creating a different machine is dead, dead, dead at the CAFC and the USSC- listen to oral argument after oral argument in 101 cases, and it’s always just dismissed flatly when some poor lawyer attempts it. My scheme is not about software patents- it’s about information results of method patents.

Rational @ 15, uh yea, I know how computers work. Claim a new kind of computer and get a patent. Claim any of the mathematically possible sequences of the CPU gates and memory states that add up to human use of the processed information resulting, and your claim should be ineligible. Claim a new, non-obvious and fully described use of the information by a non-human actor, and go get a patent.

Gene @ 8 To think of software as literature strikes you as rather ridiculous. OK. Have you spent time in the software business? Maybe you aren’t aware that Ux, or User Experience, is in many cases is the preeminent competitive factor in the success or failure of a software product. Google it- there are millions of references at every level of the software industry. Please see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User_experience for a basic overview, but the defintion is enough to make the point here:

The international standard on ergonomics of human system interaction, ISO 9241-210,[1] defines user experience as “a person’s perceptions and responses that result from the use or anticipated use of a product, system or service”. According to the ISO definition, user experience includes all the users’ emotions, beliefs, preferences, perceptions, physical and psychological responses, behaviors and accomplishments that occur before, during and after use.

Boy, that don’t sound much like mere computer parts to this country bumpkin.

“The fact that you “write” software in a human language, which is then compiled so the machine can understand the instructions, doesn’t mean software is akin to a novel or short story.”

Why the quotes around the word “write”?

I think you need to expand your understanding of the business. Software is very much akin to a novel, or short story in it’s use of symbols, tropes, sequences, ornamental design choices, etc.

And again, my focus is not on software alone, because software is only one way of generating information for human use.

My focus is on information- and how the patent system MUST relate to it going forward if it has any hope of regaining the balance that worked for so many years. The AIA and all of the interventions have been net losers- had the problem been fixed right, they never would have been needed. Humans using information is the height of abstraction. Bad claiming, which Mayo/Alice could nicely handle conducted under proper 102/103/112 standards, is a whole other situation and should not be lumped in with eligibility.

No I’m not “normal”, but no reasonable legal observer would think I’m on the short end of the discussion thus far on this thread.

Curious

August 17, 2016 07:08 pmI do hope there is no relation.

I really hope not as well. Without looking, that reg. number is probably 20+ years old, and I cannot perceive of anybody with that experience who would misstate the law that badly. As such, I really doubt there is a relation.

Briguy

August 17, 2016 06:50 pmDon, the fact that you would laugh that such claims could be seen as abstract is actually the entire purpose of this article. Yes, it is laughable. That’s the point.

Anon

August 17, 2016 04:34 pmWell said, Curious.

By the way, there is a Dennis Braswell who is a registered practitioner (Reg # 35831). I do hope there is no relation.

Curious

August 17, 2016 01:09 pmDon — Let me take this up for Gene, and respond to some of your comments.

In patent 2,026,082, every single claim begins with the phrase “A board game apparatus”

If you are aware of current US case law, the fact that a claim recites a device (e.g., a board game apparatus or computer) does not save it from being declared directed to an “abstract idea” by the courts. The Federal Circuit has frequently upheld decisions in which claims directed to machines are deemed to be directed to “abstract ideas.” The fact that you don’t appreciate evidences that you are not a practitioner in this field.

Ethical practitioners will find the previous inventions, pay the appropriate license fees for the items which were previously invented, and THEN add their device.

LOL — while I appreciate your noble sentiments, this is not done in the vast, vast majority of instances. What happens is that an infringer will infringe a patent (known or unknown, willfully or not) with no intention of paying for a license to that patent. There is a term for this — efficient infringement.

So, yes, whether you like it or not, most patents have valid prior 102 and 103 art which would preclude an inventor from legally creating such a device without at least some licensing fee paid to someone, or using a 20 year old art

Again, you are not a practitioner and do not understand what is meant by “102 and 103 art.” If 102 or 103 art exists, then the patent would not be granted — period. However, a invention (that improves upon an older invention) could infringe that older invention. Despite infringing, the older invention is not 102 art. Moreover, without anything more, the older invention is not 103 art.

Thanks again for the laughs, keep em coming!

Before you laugh — please realize that your ignorance (a term used accurate in this instance) on the issues does not give you a lot of leverage to do so.

Gene Quinn

August 17, 2016 01:04 pmDon Braswell-

I’m glad to provide you a laugh, but the laugh really should be on you. It seems that you aren’t understanding any of this.

You ask where the abstract idea is with respect to Monopoly, which only someone unfamiliar with Alice and how Alice is being applied would ask. Isn’t the real question this: Where is the abstract idea in In re Smith? If playing a game is an abstract idea, which is absolutely asinine, then playing Monopoly would have to be an abstract idea. Are you still with me? Hope you can keep up.

Perhaps you will also recall in Alice how the Supreme Court said that systems claims are abstract ideas. So that means that it is possible for a device to be an abstract idea, since after all that is what a system really is. Hope you are still with me and I haven’t lost you.

So you might want to rethink your notion that just because there is a clearly “physical thing” that means the claim couldn’t be considered abstract. That is, of course, the whole point of using Mayo and Alice together. When “physical things” are added to claims they are simply read out using Mayo after concluding they are conventional, routine, or practically conventional or mostly routine.

What you said is that rarely do patents overcome 102 and 103 issues, which as absurd as it is wrong. To get a patent the claims must be new under 102 and non-obvious under 103. There are many fully litigated patents that have over and over again withstood ever challenge and clearly they have overcome 102 and 103 repeatedly. Your attempts to make your ridiculous statement correct by altering what you actually said are amusing, but continue to show that your depth of knowledge is extraordinarily shallow.

You say: “While the examiner may have stated, “the process was new, non-obvious and appropriately described” that does not mean that the applicant could build the device without paying appropriate fees for prior art and patent claims. The patentee does not have the patent rights to build an iPhone because he has patented a “new, non-obvious and appropriately described” application for an iPhone. Hence my obvious statement stands.”

That is perhaps the most ignorant statement I’ve ever heard from someone who is allegedly a patent practitioner. Obviously you know very little about patents and patent practice. Patents can and are granted every week on inventions that if made or used would infringe on the work of others. Whether the patent owner or applicant can make and use the invention they are seeking to patent without infringing is ABSOLUTELY NOT EVER a part of any legitimate or appropriate patentability inquiry. God help your clients if you don’t understand that fundamental truth.

Your claim now that when you said in a blanket way that every patent claim has a 102 and 103 problem you were discussing licensing fees that need to be paid is laughable.

Don Braswell

August 17, 2016 12:41 pmGene, Having read your comments, my office mate and I had a good laugh. So thank you.

You clearly referenced Monopoly as an abstract idea. I must ask- where is the abstract idea you referenced? In patent 2,026,082, every single claim begins with the phrase “A board game apparatus” While some other phrases may have covered intended use, this is clearly a physical thing and it is described in some detail. So, you might want to rethink your “abstract idea” notion.

Second, as you well know, most patents build on a previous idea (whether 102 or 103).

While the examiner may have stated, “the process was new, non-obvious and appropriately described” that does not mean that the applicant could build the device without paying appropriate fees for prior art and patent claims. The patentee does not have the patent rights to build an iPhone because he has patented a “new, non-obvious and appropriately described” application for an iPhone. Hence my obvious statement stands. Ethical practitioners will find the previous inventions, pay the appropriate license fees for the items which were previously invented, and THEN add their device. So, yes, whether you like it or not, most patents have valid prior 102 and 103 art which would preclude an inventor from legally creating such a device without at least some licensing fee paid to someone, or using a 20 year old art.

Thanks again for the laughs, keep em coming!

Gene Quinn

August 17, 2016 12:04 pmDonald Braswell-

You can believe my premise is faulty, but your premise is simply wrong. You say that because Monopoly included a BOARD (your emphasis) it “was an invention.” It is true enough that an apparatus is patent eligible subject matter, but it is also perfectly true that a process is patent eligible subject matters. So despite what you seem seem to believe otherwise, processes are an invention as well and under the Patent Act deserve patent protection when they are new, non-obvious and adequately described. The invention in question in In re Smith was admitted (by the examiner) to be new, non-obvious and adequately described. Therefore, it is an invention.

You also say: “Rarely does a patent these days ‘overcome all 102 and 103 issues.’”

You can believe that if you want, but that is nonsense. In this case it is also counterfactual.

It always amazes me the lengths people like you will go to cling to the mythology you so desperately want to believe. Whether you like it or not, the examiner agreed that the process was new, non-obvious and appropriately described. And whether you like it or not, processes are patent eligible even without a BOARD.

-Gene

Donald Braswell

August 17, 2016 09:30 amIsn’t your starting premise regarding Monopoly less-than-fully disclosed? The claims in Monopoly were directed towards the BOARD of the game (see claim 1: “In a board game apparatus a board acting as a playing-held having marked spaces constituting a path or course extending about the board,…”) Thus monopoly was an invention. It probably had issues with a 103 combination of Parchesi and perhaps Milton Bradley’s first successful game called the “Checkered Game of Life” (complete with prisons and fat office), but it appears they overcame those rejections to successfully receive a patent for a system (the board) AND abstract method (the rules). In other words, Monopoly probably passed the Alice Test of today – as it had “something more.”

Second Point. Rarely does a patent these days “overcome all 102 and 103 issues.” Of course, this is what defending lawyers claim in court, but in reality most inventions these days are 24 limitations / steps of “been there, invented that already” and that last 25th step which makes the 103 combination of previous parts / methods no longer sustainable under KSR. The USPTO office’s initiative, “Clarity of the Record” requires patent examiner’s to note these previous steps that have been previously disclosed (or invented) along with the inventive step for future reference. Just some thoughts.

step back

August 16, 2016 10:51 pm@24 Anon

Congress has much more important things to do than worry about a handful of inventors and their tinker toys.

By gosh man. Congress has a two ring circus to run.

(The SCOTeti already have their clown acts in good shape. Go ask Alice.)

watch?v=Vl89g2SwMh4 on U-toob

Anon

August 16, 2016 06:11 pmGene,

I fear that leaving out process claims will not save you. The Supreme Court (and any other lower court at that court’s whim) will merely snippet out that two paragraph statement and “just apply it” to the “Gisted” claim.

Bottom line: the Supreme Court has already made the statutory categories disappear and it matter not at all which category you attempt to place your invention in.

This is an inescapable conclusion of the words that the Supreme Court have chosen to use. As I mentioned when Alice first came out, this is a wreck merely waiting to happen and the faster and harder we stomp on the gas pedal, the sooner Congress can step in and fix this problem.

Just like 1952.

Anon

August 16, 2016 06:06 pmStep back@19,

You miss the point: been there, done that.

Gene Quinn

August 16, 2016 04:02 pmPrizzi’s Glory-

You may be right that Alice would only apply to method claims, but that is far from certain. Remember in Alice the Supreme Court did not analyze the systems claims other than to say they were essentially claiming the same invention and because the method claims were patent ineligible the systems claims were likewise ineligible. It took them all of 2 paragraphs to dispose of systems claims, which are claims to a machine. Hard to believe that some machines are considered abstract ideas by the Supreme Court, but that is where we are.

I think if I were to represent anyone wanting a game patent I’d write the specification the old fashion way, but consider kit claims to the board and various pieces and parts, as well as other tangible claims. Until this gets sorted out one way or another method claims are going to contaminate many otherwise patentable inventions. Of course, I’d have the support for method claims, but probably pursue them in a separate application altogether.

-Gene

Prizzi’s Glory

August 16, 2016 02:20 pmIs it possible that only method claims to games are at risk under the Alice Mayo precedents?

The Monopoly patent claims a structure, which is a game board while this three dimensional chess patent 3,767,201 claims the three dimensional structure on which the game is played.

Gene Quinn

August 16, 2016 12:50 pmStep @10 –

At times like this I wish we had “Like” functionality on the comments here!

-Gene

step back

August 16, 2016 12:28 pm@18 Anon

But other readers could (probably are) watching.

This is a public forum.

So we should put factual arguments out for them.

Moreover some litigators could be watching …

and looking for good arguments as to why their reality-revealing “informational” invention (e.g. a new microscope, telescope, radio receiver, chemical detector, medical condition detector, etc.) should be patentable despite Mayo.

So let’s get back to giving examples of how Mayo gone wild destroys inventing in the reality revealing realm and forget about the ad hom bite backs.

OK?

Anon

August 16, 2016 10:02 amStep back @14,

Normally I would agree with you fully.

But this poster is not normal, and has anointed himself to be some type of “savior” all the while NOT understanding either the technical facts, nor the underlying law.

He has been unwilling to listen to reason, and thus, rebuke is in order.

Curious

August 16, 2016 09:51 amsoftware = hardware

Put software (running on hardware) or hardware (alone) in a black box and they are indistinguishable.

Software is a way of describing (instructing) how to operate a computer — it is not an “abstract idea.” Moreover, software does not exist outside of a computer (or computer component). A description of software can be an abstraction, but so can a description of a mechanical device. For example, when I state that something is a “motorcycle,” it is an abstraction that can cover hundreds of thousands of different embodiments. Alternatively, if I describe “welding piece A to piece B,” that is also an abstraction since it abstracts away a multitude of steps that are involved as part of the welding.

Claims are created through the use of words, and words are, by their very nature, abstractions. Unless we are dealing with inventions defined by atomic elements (e.g., materials), the invention is going to be defined as an abstraction.

Do you have a different idea of how computer work?

To most, it is just magic.

angry dude

August 16, 2016 08:53 amsoftware = hardware

end of discussion

A Rational Person

August 15, 2016 11:21 pmYou Know Who I Am@7

“If the result of a method is information, and the method recites no new mechanical or chemical changes, that invention is abstract if the value of the infringement is based on human consumption of the resulting information. If a non-human actor is consuming the information result of the method, and the method meets the requirements of 102/103/112, a patent should issue.”

But virtually every software method claims effectively recites a “mechanical change”, i.e., a change in tiny “switch” computer.

From the definition of “software” from Wikipedia:

“At the lowest level, executable code consists of machine language instructions specific to an individual processor—typically a central processing unit (CPU). A machine language consists of groups of binary values signifying processor instructions that change the state of the computer from its preceding state. For example, an instruction may change the value stored in a particular storage location in the computer—an effect that is not directly observable to the user. An instruction may also (indirectly) cause something to appear on a display of the computer system—a state change which should be visible to the user. The processor carries out the instructions in the order they are provided, unless it is instructed to “jump” to a different instruction, or interrupted.”

EVERY state change in a computer involves a PHYSICAL CHANGE of one or more “switches” in the computer. That’s how software and computers work.

Do you have a different idea of how computer work?

step back

August 15, 2016 10:38 pm@11 Anon

I don’t think it helps to say “you are ignorant” if you want to engage someone in a debate because such ad-hominums will make them simply walk away.

I think we can come up with many examples of where mere “information” has real life severe consequences and it would be irrational to say not patent eligible.

Consider the receiver end of a radar system.

It may provide “mere information” about when and from where the enemy’s missiles are homing in to sink your battle ship. You can take evasive maneuvers or just ignore that “mere information”. Your call.

(Wasn’t that the punch line to some joke about a Nova Scotia lighthouse and a US battle fleet? IIRC: Admiral “You don’t understand this is a US Navy Destroyer and we will smash right through you. Now give way I say!”. Other party on radio link: “This is Nova Scotia Light house number 351. It’s your call. Do as you want.” -another example of “mere” information)

Curious

August 15, 2016 09:10 pmI have yet to encounter a coherent argument that explains why my definition is unworkable, or does not comport with current law or doctrine, or is too arbitrary for use as a line-drawing tool.

To borrow an expression from ‘anon,’ I’m not surprised with your eyes clinched so tight. Current statutory law is “any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof.” Following statutory law and Congress’ intent, anything under the sun made by man is patent eligible.

copyright for those items of software and information technology that are not patent-eligible

is essentially useless. All that protects is lazy copying. It does not prevent copying functionality.

When a non-human actor responds to information, that response can never be “abstract”. When a person responds to information, it can only be “abstract’.

OK. I’ve developed a new algorithm for detecting gold using a typical metal detector. The algorithm causes an audio cue that indicates that gold — and no other metal — has been found. Patent eligible?

What if I employ the same new algorithm with a combined metal detector and robotic digging tool so that when the algorithm detects gold, the robotic digger digs it up. Patent eligible?

Curious

August 15, 2016 08:53 pmSoftware has too much in common with literature and other works of authorship

Look at the coursework for the average computer science major, electrical engineer major, and the English literature major, and then come back to me as to which of the two (electrical engineer major or English literature major) has more in common with the computer science major.

One might argue that a mustang or corvette are “works of art,” but in the end, they are far more objects created by engineering than art. While one can build “artistry” into computer software, the same can be said about any object designed by a mechanical or electrical engineer. Few objects are completely utilitarian.

Anon

August 15, 2016 08:41 pmYKWIA,

I have to say, that you are really displaying your ignorance of the law with that long winded rant.

Your own attempts speak out against your views. Start over and learn the law from scratch – without your preconceived biases.

step back

August 15, 2016 06:56 pm@7 YKWIA:

Your doctor just received mere “information” from the lab (by way of a merely generic digital information relaying means).

It says you are missing a vital chemical among your vital bodily fluids and you will become deceased unless it is replenished within 4 hours.

But heck.

It’s only abstract information.

It’s not “real”.

So let’s just throw it away and forget about.

What’s the harm?

Enjoy the next 3:58 Hours/mins.

Apologies that it took 2 of your minutes to read this. 🙂

Alex in Chicago

August 15, 2016 06:29 pmI may be a bit of a blackjack N00B for asking, but don’t you have to do all that in normal blackjack?

Gene Quinn

August 15, 2016 05:48 pmYou Know Who I Am-

You write: “Allowing monopolies on whole swaths of essentially literary genres is too restrictive of human freedom, and cases can never be reliably adjudicated.”

RESPONSE: Agreed. Monopolies should not be granted on literature. Luckily, patents are NOT granted on literature. But patents aren’t monopolies either, despite what the Supreme Court likes to think. See:

https://ipwatchdog.com/2012/09/03/debunking-innovative-copycats-and-the-patent-monopoly/id=27749/

You also write that software is essentially literature, which is curious to say the least. Now I’m not saying that all software should be patented, clearly it shouldn’t all be patented, but all software should be patent eligible. Whether a patent should issue should be decided by 102, 103 and 112, not 101.

To think of software as literature strikes me as rather ridiculous. Software directs a machine to operate. Literature does not direct any processes. The fact that you “write” software in a human language, which is then compiled so the machine can understand the instructions, doesn’t mean software is akin to a novel or short story.

-Gene

You Know Who I Am

August 15, 2016 04:55 pmThere are basically three positions on software patents; none should be allowed, because software is intangible and thus abstract in every case, all should be allowed (that meet 102/103/112 requirements) because software is made by the hand of man, and some should be allowed, based on various tests such as a technological arts test, or improvement of computers, or Mayo/Alice.

I cannot abide the “all should be allowed” position. Software has too much in common with literature and other works of authorship; it models and simulates aspects of the world with individual works of creative expression created by writing in a language. Allowing monopolies on whole swaths of essentially literary genres is too restrictive of human freedom, and cases can never be reliably adjudicated.

The line between copying and inspiration is always sui generis. Patenting the expression of general ideas rather than specific works would be too limiting. After “Jaws”, nobody could make a fish movie for 20 years (nominally- the scandal of continuation practice is for another day). After “Star Wars” nobody could do a space movie – the doctrine of equivalents exists to ensure that result.

Copyright law has evolved to handle these kinds of tensions. This is one of the basic reasons we have different law for copyright and patent. (Please save the trope that copyright does not cover utility and that’s what patents are for. There are always gray areas like training films or the “gaming” arts- the exact point of this article.

I could live with the “no software patents, period” position, but I don’t think that is in the best interest of the economy or in-line with the Constitutional right to patent in some instances. Note to pro-patent extremists: I agree with you on the basic values of the patent system. You should recognize that when countering what I have to say.

Thus I am in the “sometimes” camp, and I think the 8 members of the USSC are too, as are the 11 of the CAFC. All have, to one degree or another, expressed some notion of when “sometimes” should be, and there is a plurality that the framework for the distinction must be found somewhere in the “abstract ideas exception” doctrine. Software is not the only kind of invention facing abstraction issues. The problem really swings around information, but by proxy we talk about software. Yet no plurality has formed about the definition of abstraction, because it’s a tricky problem.

The reason, stated clearly in Bilski, and generally in many of the subject matter cases, is human freedom. The ability to add to and draw from the “storehouse of knowledge” that belongs to all mankind. The ability to associate and design our commerce without interference. The ability to pass along aspects of culture and ways of organizing ourselves are rights that must not be infringed-any more than the patent right may be. The “abstract ideas exception” is the place where that freedom is protected.

The other problem with a definition is that abstraction arises in two totally different contexts in patent law. It differs from what kinds of things can be patented (eligibility) and which specific purported inventions can be patented (patentability). Bilski rejected a physical or tangible structure as a requirement for eligibility as a “process”, so there is a big challenge fitting always abstract information to a “sometimes” allowable framework. The “technical solutions to technical problems” test is as useless a tabula rosa as the notion of “abstract ideas”. The EU is basically on the same “know it when we see it” standard as we are.

Abstraction at patentability is something else entirely. That is the true use of Mayo/Alice; to help insure claims are not being drawn to ideas about solutions, rather than actual solutions to problems. It’s a streamlined, combined view of 102/103/112. It should only apply to already eligible inventions and should not be considered a test of eligibility, but of patentability. If an invention meets those requirements, it can’t be “abstract” in this second sense. Gene Quinn demands a definition of abstract ideas, and I agree with him on that point.

I have a workable, practical definition with impeccable lingual and philosophical justification.

Simply put: The word abstract has, as its Latin root, the act of “drawing away” When people draw meaning, they are creating abstractions. No abstraction can exist without a human mind to apprehend it. When a non-human actor responds to information, that response can never be “abstract”. When a person responds to information, it can only be “abstract’.

If the result of a method is information, and the method recites no new mechanical or chemical changes, that invention is abstract if the value of the infringement is based on human consumption of the resulting information. If a non-human actor is consuming the information result of the method, and the method meets the requirements of 102/103/112, a patent should issue.

The test is simple, does not impede innovation of self-driving cars or self-toasting toasters or of a vast array of artificial intelligence and other innovations that information technology may enable- but it does prevent wholesale patenting of computer implemented business methods, or any other kind of model or simulation whose economic value arises from the use of information people draw into their minds and respond to.

This does not rule out on any level the devices that store, process, or present information- because those items aren’t methods. This still leaves copyright for those items of software and information technology that are not patent-eligible, but still benefit economically from appropriate IP protection.

In terms of eligibility only- MPEG patents; yes. Blackjack patents; no. Tesla Autopilot: yes. Showing nearest pizza on a map; no. Opening a rubber press based on rules: yes. Finding fetal cells in maternal plasma: no. Designing a database with one table: yes. Finding the lowest credit card rate: no.

I have yet to encounter a coherent argument that explains why my definition is unworkable, or does not comport with current law or doctrine, or is too arbitrary for use as a line-drawing tool. It’s a darn sight less arbitrary than what we have now and what we are likely to have until information/abstraction is reliably defined in patent law.

step back

August 15, 2016 01:47 pm@4 reiterated: Nothing is patentable.

Not even real time monitoring of an oil well:

TDE PETROLEUM DATA SOLUTIONS v. AKM ENTERPRISE (8/15/2016) J. Lourie and friends:

http://www.cafc.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/opinions-orders/16-1004.Opinion.8-11-2016.1.PDF

Curious

August 15, 2016 01:36 pmIn re Smith:

On the first step, we conclude that Applicants’ claims, directed to rules for conducting a wagering game, compare to other “fundamental economic practice[s]” found abstract by the Supreme Court.

CLS Bank:

At the same time, we tread carefully in construing this exclusionary principle lest it swallow all of patent law

A variation of Blackjack is not some “fundamental economic practice.” The Supreme Court used “fundamental” to preface “economic practice” — not “any.” While the Supreme Court deserves blame for presenting vague tests, the Federal Circuit deserves even more blame for ignoring the limitations that the Supreme Court placed on the application of the “abstract idea” exception.

We went from a prohibition on “basic tools of scientific and technological work” to a prohibition on games. There is absolutely no justification (legally or policy-wise) for preventing patents on these kinds of inventions. This is a perfect example of a court judicial activism.

step back

August 15, 2016 10:25 amGene, Gene,

When will you understand?

Nothing is patentable unless the “we” of the Supreme Court decide otherwise.

At their root, all inventions are directed to the idea that human beings, perchance even the rabble commoners among them, can invent at all. The latter is an abstract, fundamental and dangerous idea.

If we allow inventors to have treacherous thoughts like the notion that “they” and not the market invented, then inventors might wish to have “rights”.

The royal “we” of the Supreme Court cannot allow the little people to have “rights”.

Imagine sir what havoc would ensue if the commoners were given “rights”!

😉

http://patentu.blogspot.com/2016/06/you-didnt-inventbuild-that-part-ii.html

patent leather

August 15, 2016 10:01 amthere’s two problems I see with the Smith decision:

1) “On the first step, we conclude that Applicants’ claims, directed to rules for conducting a wagering game, compare to other “fundamental economic practice[s]” found abstract by the Supreme Court. See id. As the Board reasoned here, “[a] wagering game is, effectively, a method of exchanging and resolving financial obligations based on probabilities created during the distribution of the cards.”

OK, so what if the invention was not a wagering game. Let’s say it was a video game utilizing cards (or any other type of indicia) but no wagering takes place. Is this a “fundamental economic practice?” So by adding a step of “wagering” it turns into a FEP. What if it were claimed more broadly (without any “wagering”)?

2) “But appending purely conventional steps to an abstract idea does not supply a sufficiently inventive concept.”

This is in tension with Bascom (although Smith did come first). But given the literal language in Smith, step 2 of Alice is basically dead unless you have a non-obvious non-abstract idea inside the claim. But if you have a “non obvious-non-abstract idea” inside the claim, then clearly you wouldn’t have a 101 problem anyway. This seems to ratify Flook’s “point of novelty test” which was overruled in Diehr (and despite some opinions to the contrary, was not resurrected by some of the later decisions).

Michael Risch

August 15, 2016 08:44 amThis was a close case even before Alice. See my discussion of games in “A Surprisingly Useful Requirement”: http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1790463

Anon

August 15, 2016 08:20 amVoid for vagueness.

(That would be the law as written by the Supreme Court)