“Prior art also will no longer have any geographic limitations.”[1]

The American Invents Act’s (AIA) provisions related to expanding the availability of prior art apply to US applications having an effective filing date after March 15, 2013. Aside from the language of the AIA there are few, if any, signal posts from the courts or the USPTO as to scope of the expansion. As more and more applications are examined and litigated under the AIA provisions, this can leave patent owners and practitioners anticipating the expansion.

The American Invents Act’s (AIA) provisions related to expanding the availability of prior art apply to US applications having an effective filing date after March 15, 2013. Aside from the language of the AIA there are few, if any, signal posts from the courts or the USPTO as to scope of the expansion. As more and more applications are examined and litigated under the AIA provisions, this can leave patent owners and practitioners anticipating the expansion.

One area of uncertainty are intervening disclosures. Although what qualifies as art under the AIA can be distilled to disclosures before a patent application, both pre-AIA and AIA created exceptions for intervening disclosures in Section 102(a)(2). Intervening disclosures are defined by an earlier filing date, but a later publication date and are sometimes referred to as secret prior art. Intervening disclosures apply only to US patents, US publications, and PCT applications. Other types of disclosures, such as disclosures at a Beijing conference in Chinese would need to be considered under Section 102(a)(1).

Where is this expansion for intervening disclosures going to come from? Mainly from two primary sources: 1) US patents or publications that have foreign priority claims; and 2) PCT applications published in a language other than English, regardless of foreign priority claim. Based on USPTO stats, in 2015 approximately 170,000 of the 326,000 US patents were obtained by foreign applicants.[2] The trend is that more US patents are being granted to foreign applicants and the US patents and publications of these foreign applicants may have earlier foreign priority dates.[3] In 2015, WIPO reported that approximately 200,000 PCT applications were filed and roughly 97,000 were in a language other than English.[4] Both of these primary sources indicate the potential of double the number of references in one year alone. The potential doubling of available intervening disclosures would create significantly more prior art.

The expansion will not be without limits and exceptions. This presents patent owners and practitioners the opportunity to participate in establishing these signal posts to shape the expansion. Moving forward in the next five years the questions as to the extent that current limitations and potential exceptions will define this expansion of intervening disclosure.

Pre-AIA Section 102(e) and Hilmer

Before the AIA, Section 102(e) created exceptions for intervening disclosures and provides that:

A person shall be entitled to a patent unless—

(e) the invention was described in – (1) an application for patent, published under section 122(b), by another filed in the United States before the invention by the applicant for patent . . . except that an international application . . . shall have the effects for the purposes of this subsection of an application filed in the United States only if the international application designated the United States and was published . . . in the English language.

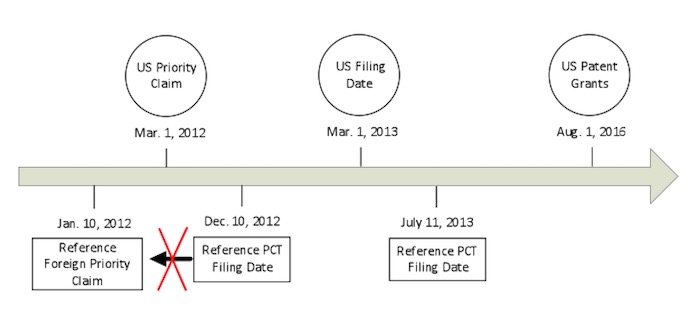

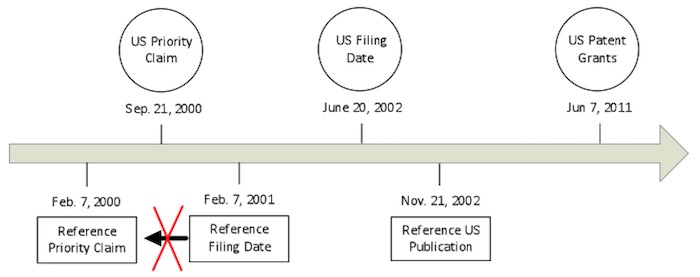

Under pre-AIA Section 102(e), one significant limitation on intervening documents is that if these intervening documents are only available as of its US effective filing date, not an earlier foreign priority date. This is referred as the Hilmer doctrine, which are two 1966 CCPA cases[5] holding that intervening disclosures are not available as of its foreign priority date.

The familiar situation is illustrated as follows, with circles indicating the claimed invention and rectangles indicating the intervening disclosure.

Courts and the USPTO have continued to apply the Hilmer doctrine to find intervening documents are not available under pre-AIA Section 102(e). This has helped applicants eliminate potential intervening disclosures by allowing applicants to obtain a benefit of a foreign priority, but denying the intervening disclosure the similar effect.

Redefining Intervening Discloses – AIA Section 102(a)(2)

The AIA eliminates the Hilmer doctrine by stating that “effectively filed” refers to the earliest priority date, US or foreign.[6] The AIA removed Section 102(e) and redefined intervening disclosures in Section 102(a)(2), which provides that:

A person shall be entitled to a patent unless—

(2) the claimed invention was described in a patent issued …, or in an application for patent published or deemed published …, in which the patent or application, as the case may be, names another inventor and was effectively filed before the effective filing date of the claimed invention.

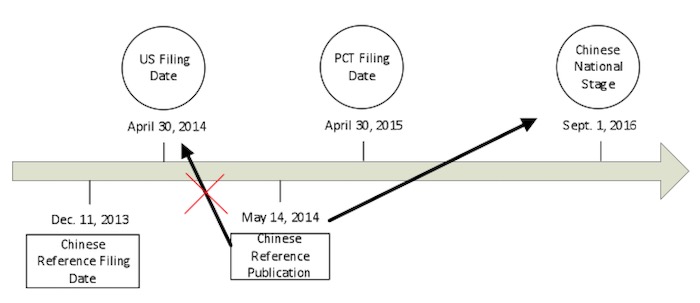

The difference is illustrated as follows.

The reference would be available under Section 102(a)(2) based on its foreign priority date. As of now there is no requirement that the reference perfected its foreign priority (reference in application and certified translation). Of course, under the pre-AIA, the Hilmer doctrine would cut off the foreign priority date, and the reference would not be available under pre-AIA Section 102(e). The expansion of the intervening disclosures, i.e. secret prior art, is clearly evident.

Note that in this example if the intervening disclosure was only published in foreign country, and not in the US or a PCT application, then the reference would not qualify under Section 102(a)(2) or pre-AIA Section 102(e). This is a first limitation on the geographically expansion of intervening documents under the AIA.

The first limitation becomes important when one considers the increasing number of Chinese patent documents[7] are published in China only without filing a corresponding PCT or entering the US. Thus, such Chinese patent documents would not qualify as intervening disclosure because there are no subsequent US applications or patents. However, those Chinese patent documents could be available as art against a subsequent Chinese application. The situation is demonstrated below in which the Chinese application was published before the 18-month period.

Section 102(a)(2) is expected to lead to an expansion of intervening disclosures. With more tools for searching foreign publications, a large potential resource of intervening disclosures, and USPTO guidelines encouraging broad searches there is expected to be an increase in using intervening disclosures in both anticipation and obviousness rejections. However, due to the length of prosecution, there have been no decisions to date defining the expansion under Section 102(a)(2) and many of the same questions raised early still remain.[8]

Despite the anticipated expansion of intervening disclosures, there are still limits the types of documents available as intervening disclosures. Two of these limits are familiar to practitioners under pre-AIA Section 102(e) and include: 1) inventive entity; and 2) support in priority document. In addition, the AIA created three new exceptions: A) disclosures obtained from inventor; B) intervening disclosure by another; C) ownership by same person.

Limitation 1) Inventive Entity

The pre-AIA Section 102(e) used the language “by another” and AIA Section 102(a)(2) uses the language “names another inventor.” The pre-AIA Section 102(e) standard required strict identity of inventorship and if not then the intervening disclosure was available as prior art. Applicants did have the available to file a declaration that the intervening disclosure was not by another.

The pre-AIA Section 102(e) used the language “by another” and AIA Section 102(a)(2) uses the language “names another inventor.” The pre-AIA Section 102(e) standard required strict identity of inventorship and if not then the intervening disclosure was available as prior art. Applicants did have the available to file a declaration that the intervening disclosure was not by another.

One item to consider is that foreign priority applications do not always identify inventors. This may make determining if the foreign priority application names another inventor challenging.

Limitation 2) Support in Prior Document

In Dynamic Drinkware, LLC, v. National Graphics, Inc., the Federal Circuit found that the petitioner in an Inter Partes Review (IPR) failed to carry its burden that the intervening disclosure, Raymond, was entitled to its filing date of its US provisional application. The Federal Circuit rejected the presumption that the intervening disclosure was entitled to its priority date. A reference patent is only entitled to claim the benefit of the filing date of its provisional application if the disclosure of the provisional application provides support for the claims in the intervening disclosure in compliance with pre-AIA Section 112, ¶ 1.

Instead, the Federal Circuit found that for a petitioner to rely on the benefit of an earlier filing date, the petitioner has the burden to show:

(1) that the intervening disclosure is entitled to the benefit of the priority document by showing support for the intervening disclosure’s claims in the priority document, and

(2) that the anticipatory disclosure of the intervening disclosure is shared by the priority document.

This burden requirement was followed by the PTAB in Ariosa Diagnostics, Inc. v. Illumina, Inc., IPR2014-01093 (2016) that found the petitioner failed to carry its burden that the intervening disclosure was entitled to the US priority date as shown below:

In particular, the PTAB found that the incorporation of reference of the priority document was not sufficient to show that “the material being relied upon as teaching the subject matter of the challenged claims must be carried through from that earlier filed application to the patent document being used against the claim.”

Separately, the PTAB also found conclusory statements in an expert declaration that the priority document provided sufficient written description support for the intervening disclosure was insufficient.[9] Thus the intervening disclosure, which was used in a grounds for obviousness, was not available under pre-AIA Section 102(e) as a reference. Other decisions at the PTAB have also found references available under pre-AIA Section 102(e) based on Dynamic Drinkware.[10]

However, Dynamic Drinkware was decided based on pre-AIA Section 102(e) and in footnotes the Federal Circuit indicated that this decision does not consider AIA Section 102(a)(2).[11] Dynamic Drinkware based its decision on In re Wertheim, which the USPTO Examination Guidelines indicate was displaced by the AIA Section 102(d).[12] In its guidelines, the USPTO states:

Thus, as was the case even prior to the AIA, there is no need to evaluate whether any claim of a U.S. patent, U.S. patent application publication, or WIPO published application is actually entitled to priority or benefit under 35 U.S.C. 119 120, 121, or 365 when applying such a document as prior art.

Despite these guidelines, this does not mean that the applicant cannot or should not raise the issue during prosecution or in subsequent legal proceedings. The open question is whether the courts will apply draw similar conclusions when interpreting Section 102(a)(2) as Dynamic Drinkware. In addition, the 112 requirements under Nautilus may provide ample challenges that priority document fails to support the intervening disclosure. Thus, seeking to avoid such burdens and limitations, one may avoid using intervening disclosures under Section 102(a)(2) if different disclosure under Section 102(a)(1) can be applied.

In addition to these limits on intervening disclosures, the AIA also created three exceptions for 102(a)(2) under 102(b)(2). In the current environment, without any guidance on the exceptions, the best resource for considering these exceptions is to refer to the USPTO comprehensive training materials. Asserting these exception in prosecution may necessitate the need to submit a declaration under 37 CFR § 1.130.

Exception 102(b)(2)(A) Intervening Disclosures Obtained From Inventor

This exception applies to the intervening disclosures itself and states:

102(b)(2)(A) – the subject matter disclosed was obtained directly or indirectly from the inventor or a joint inventor

The issues that arise from this exception is: i) defining what is the subject matter and ii) how to demonstrate the “obtained directly or indirectly from the inventor or a joint inventor.” For the subject matter, the USPTO guidelines indicate that same subject matter is not equated to obviousness. If the intervening disclosure is cited as an anticipatory reference it should have the same subject matter.

Regarding the evidence needed to demonstrate that subject matter was obtained it is evident that if the intervening disclosure by an overlapping inventive entity that the showing should be similar to “not by another” showing under pre-AIA Section 102(e). However, if the intervening disclosure is by someone outside of the inventive entity then the open question is what is sufficient for this showing? For example, must the showing be similar to a derivation proceeding, which is also a new type of proceeding, or something else?

Exception 102(b)(2)(B) Collateral Disclosure by Another

Following the prior disclosure, the AIA provides another exceptions for collateral disclosures prior to the effective filing date of the claimed invention. These collateral disclosures may be made by the inventor(s) or another who obtained it from the inventor(s).

This exception to intervening disclosures states:

102(b)(2)(B): the subject matter disclosed had, before such subject matter was effectively filed under subsection (a)(2), been publicly disclosed by the inventor or a joint inventor or another who obtained the subject matter disclosed directly or indirectly from the inventor or a joint inventor

By invoking this exception, there are several pitfalls. First, the collateral disclosure must be within the 1 year grace period otherwise the collateral disclosure could be available under 102(a)(1). Although this exception is similar to 102(b)(1)(B) for prior disclosures, the difference is that the collateral disclosure must be made before the effective filing date of the intervening disclosure under 102(b)(2)(B), but only made before the disclosure date under 102(b)(1)(B). Also the collateral disclosures for under 102(b)(1)(B) must be within the 1 year grace period, but it is possible that the collateral disclosure could be outside of the 1 year grace under 102(b)(2)(B).

Second, if disclosed in a patent application then that collateral disclosure might be a reference under Section 102(a)(1) or an intervening disclosure under Section 102(a)(2). This might practically limit the disclosures to non-patent documents. If limited to non-patent documents then it may be difficult to establish that the collateral disclosure sufficiently disclosed the subject matter.

Third, the uncertainty in how “subject matter” will be interpreted as discussed above. The subject matter disclosed in the collateral disclosure must be found in the intervening disclosure. Three examples illustrate some of the potential issues:

| Collateral Disclosure | Intervening Disclosure | Exception – based on subject matter |

| Discloses species | Discloses generic and discloses species | Yes |

| Discloses species | Discloses list of species, but no generic | Partial to only the disclosed species |

| Generic | Species | No |

This exception may prove limited in its use and widespread adoption. Because of the potential pitfalls this exception may be used when all other options are eliminated.

Exception 102(b)(2)(C) Ownership by Same Person

The third exception applies when the intervening disclosure and claimed invention are owned by a same person. The ownership must be established as of the effective filing date of the claimed invention. The date to establish ownership may be a later date that what was required under pre-AIA which requires establishing common ownership at the time of invention. This prevents an company’s own disclosures that are from a different inventive group from being used as intervening disclosures in anticipation rejection and obviousness rejections. Previously, pre-AIA 102(e) intervening disclosure own by the same person would only be excluded if applied in obviousness rejections under 103(c). Similar to pre-AIA, to invoke this exception during prosecution a statement of common ownership is sufficient and no declaration is needed.

One note of caution is that when the disclosure fails within the grace period, the disclosure can be applied as a prior disclosure under Section 102(a)(1) and/or an intervening disclosure under Section 102(a)(2). The USPTO is encouraging Examiners to make both rejections. By invoking the exception under 102(b)(2)(C) the rejection based on Section 102(a)(2) may be overcome but the rejection based on Section 102(a)(1) would still remain.

This same person also applies to joint research agreement (JRA) between 1 or more parties that is effect before the effective filing date of the claimed invention and undertaken within the scope of the JRA. To take advantage of this exception, the application must disclose or is amended to disclosure the parties of the JRA. It remains to be seen whether courts will allow patent owners to amend the granted patents to take advantage of this exception.

Available for Obviousness

As with pre-AIA, to be available as a reference in an obviousness rejection, either alone or in combination, the disclosure must be available under 102(a)(1) and/or 102(a)(2). Current guidelines are not requiring the examiner to specify which section the reference is available under and thus it is left to the applicant to determine and challenge if necessary.

Conclusion

From a starting point the exception and limitation give rise to the possible of restricting the expansion. Based on the initial assessment it appears difficult to proceed with exceptions 102(b)(2)(A) and 102(b)(2)(B) and applicants would be advised to proceed with caution in invoking these exception. The exception under 102(b)(2)(C) for same person may provide the most utility to avoid intervening disclosures. In addition, other limitations may practically restrict what types of documents can be available and further limit the expansion of intervening disclosures.

As more applications are examined, appealed, and litigated, the anticipated expansion of intervening disclosures will begin to take shape in the context of existing limitations and new exceptions.

_______________

[1] Committee Reports, 112th Congress (2011-2012), House Report 112-098 – Part 1

[2] Not all foreign applicants have foreign priority claims, several already have US priority claims.

[3] http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/ac/ido/oeip/taf/st_co_15.htm

[4] http://ipstats.wipo.int/ipstatv2/pmhindex.htm?tab=pct

[5] 359 F.2d 859, 878 (C.C.P.A. 1966)

[6] § 102(d) eliminates this distinction by providing that a published application or patent is “effectively filed” for the purposes of § 102(a)(2) on the date of actual filing in the U.S. or the date that an application under §§ 119, 365(a), or 365(b) was filed.

[7] Michael Sneddon, “Inside Views: A Look At The Huge Upswing In China Patent Filings” (finding 705,000 domestic filings in 2013, but only 30,000 of those filed abroad or less than 5%).

[8] Gene Quinn, “America Invents: The Unintended Consequences of Patent Reform.”

[9] Cisco Systems, Inc. v. Constellation Techs., LLC, IPR2014-00914 (2015)

[10] Masterimage 3D, Inc. V. Reald Inc., IPR2015-00035 92016)

[11] “Because we refer to the pre-AIA version of § 102, we do not interpret here the AIA’s impact on Wertheim in newly designated § 102(d).”

[12] Examination Guidelines for Implementing First Inventor to File Provisions of the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act, 78 FR 11059 at 11077 (col. 1)(February 14, 2013).

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

No comments yet.