Mark Twain, circa 1907. Public domain.

There might be no writer more important to the development of American literature than Samuel L. Clemens, known better by the pseudonym Mark Twain. Even Ernest Hemingway has admitted in writing that “all modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn.”

Twain was a humorist, a chronicler of human hypocrisy and was the first mainstream writer to capture the vernacular of the American South, among other regions. Even his pen name, which he started using in 1863, was a play on terminology used by those traversing the famed Mississippi River; “mark twain” meant that the river water reached the second mark on a depth-measuring line indicating that the river in that area was deep enough for a steamboat to pass.

One of Twain’s more strongly held beliefs was that the people of the United States had a unique drive and propensity for innovation, which made this nation a special one. In a piece titled “The Bolters in Convention” published by the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise, Twain opines that “we are fearfully and wonderfully made, and we glorious Americans will occasionally astonish the God that created us when we get a fair start.” In an 1890 speech titled “On Foreign Critics”, Twain notes that “we are called the nation of inventors. And we are. We could still claim that title and wear its loftiest honors if we had stopped with the first thing we ever invented, which was human liberty.”

In Mark Twain’s 1889 novel A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, a fictional account of an American engineer traveling back in time to the days of King Arthur’s Camelot who attempts to bring modern innovation into the past, we can see evidence of Twain’s stirring defense of strong patent laws. At the beginning of chapter nine, the American narrator Hank Morgan discusses how he visits tournaments to study them and:

“see if I couldn’t invent an improvement on it. That reminds me to remark, in passing, that the very first official thing I did, in my administration – and it was on the very first day of it, too – was to start a patent office; for I knew that a country without a patent office and good patent laws was just a crab, and couldn’t travel any way but sideways or backways.”

In addition to all the accolades that can be bestowed upon Mark Twain, he was also an inventor himself. As the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office itself has reported, Mark Twain’s real-life alias Samuel Clemens was named as an inventor on three U.S. patents granted to the author during the 19th century.

In addition to all the accolades that can be bestowed upon Mark Twain, he was also an inventor himself. As the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office itself has reported, Mark Twain’s real-life alias Samuel Clemens was named as an inventor on three U.S. patents granted to the author during the 19th century.

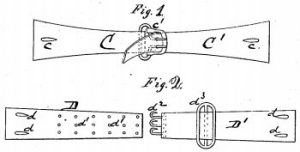

This Monday, December 19th, marks the 145th anniversary of the issue of the first U.S. patent granted to Clemens. U.S. Patent No. 121992, titled Improvement in Adjustable and Detachable Straps for Garments, was issued in 1871 and protected an elastic strap for vests, pantaloons and other clothes, which can be detached for use on multiple clothing items, the advantages of such “are so obvious that they need no explanation.”

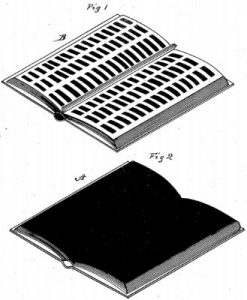

Twain’s next U.S. patent was granted in June 1873. U.S. Patent No. 140245, entitled Scrap-Books, disclosed the production of a self-pasting scrapbook in which pages are entirely covered, or covered on one side, “with mucilage or other suitable adhesive substance.” Twain’s patent also discloses scrapbooks in which the adhesive substance is applied at intervals and not across the entire face of a scrapbook page. “In either case the scrap-book is, so to say, self-pasting, as it is only necessary to moisten so much of the leaf as will contain the piece to be pasted in, and place such piece thereon, when it will stick to the leaf,” the patent reads.

Twain’s next U.S. patent was granted in June 1873. U.S. Patent No. 140245, entitled Scrap-Books, disclosed the production of a self-pasting scrapbook in which pages are entirely covered, or covered on one side, “with mucilage or other suitable adhesive substance.” Twain’s patent also discloses scrapbooks in which the adhesive substance is applied at intervals and not across the entire face of a scrapbook page. “In either case the scrap-book is, so to say, self-pasting, as it is only necessary to moisten so much of the leaf as will contain the piece to be pasted in, and place such piece thereon, when it will stick to the leaf,” the patent reads.

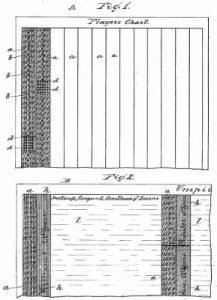

Twain had a great wit, so it’s not surprising to see that his third patent was directed at a board game designed to test the historical knowledge of players. U.S. Patent No. 324535, titled Game Apparatus, was issued to Clemens in August 1885 and disclosed an “instructive and amusing game” consisting of players’ charts with rows or columns of numbers accompanied by a hole; the numbers represent historical years and players compete by placing a pin in a hole and stating an event taking place in the year associated with that hole. “For instance, beginning with the first column and the year 1066, we have the battle of Hastings and the overthrow of the Saxons, and so on,” the patent reads.

Twain had a great wit, so it’s not surprising to see that his third patent was directed at a board game designed to test the historical knowledge of players. U.S. Patent No. 324535, titled Game Apparatus, was issued to Clemens in August 1885 and disclosed an “instructive and amusing game” consisting of players’ charts with rows or columns of numbers accompanied by a hole; the numbers represent historical years and players compete by placing a pin in a hole and stating an event taking place in the year associated with that hole. “For instance, beginning with the first column and the year 1066, we have the battle of Hastings and the overthrow of the Saxons, and so on,” the patent reads.

It would be interesting to hear Twain’s thoughts on the current state of the U.S. patent system, given reports of patent examiner abuses at the USPTO as well as the recent establishment of administrative courts, which amount to little more than intellectual property-killing death squads. While we can’t get Mr. Clemens himself to describe which direction the U.S. crab is currently travelling, we can recognize that perhaps the most celebrated American novelist of all time was not only a patent owner but a champion of a strong patent system supporting national economic success.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

One comment so far.

Eric Berend

December 21, 2016 04:46 amLet us hope that greater understanding and reverence for the Founding Fathers’ essential governance designs as regards intellectual property, returns someday soon to the U.S. Congress and the other two Branches of Federal Government; as Clemens well understood, incentivizing ingenuity as a mutual compact of the public and private interest, is best for any nation’s economy.