Citation analysis has been routinely used for several decades to help assess patent quality and determine how patents impact the competition and affect the world at large. A greater number of forward citations for a given subject (published application or issued patent) may imply its importance in a given technical space, its monetary value, its potential for being infringed, or its shared interest by others in the technology.

Most patent professionals recognize that a raw count of the number of forward citations to a patent can be an indicator of a patent’s value. However, a mere count is insufficient because decoding the citations to support meaningful decisions is still a challenge.

To further complicate matters, important and meaningful citations are virtually always underreported making them unavailable to patent analysts for consideration.

This article reveals new data that may render traditional citation analysis inadequate, and discusses the who, what, and when of each citation as an important consideration when attempting to derive value from careful examination of the complete forward citation record.

What is a Citation?

First a brief background on citations: Citations come in two principal flavors—forward and backward (aka reverse). But in reality, forward citations are a derived artifact of reverse citations. The reverse-ness and forward-ness of a citation depends on the point of view.

First a brief background on citations: Citations come in two principal flavors—forward and backward (aka reverse). But in reality, forward citations are a derived artifact of reverse citations. The reverse-ness and forward-ness of a citation depends on the point of view.

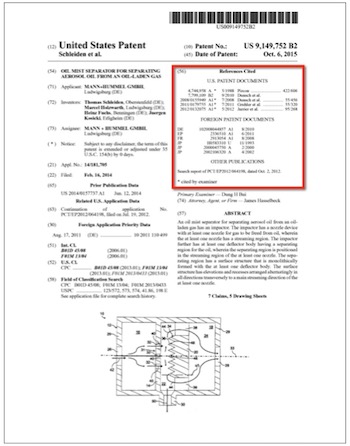

All citations begin life as backward citations. In the US, they are created by inclusion on an Examiner’s List of Cited Art (via form 892) or by an applicant’s submission on an Information Disclosure Statement (IDS) (via form 1449). When a patent grants, citations are listed on the front page of the published document. From the perspective of the cited art, backwards citations become their forward citations.

Unlike published patents, published applications do not contain the cited art on the front page even if they exist at that time. Backward citations are determined by processing the 1449 and 892 forms in the US, and corresponding forms from other jurisdictions.

Databases then resolve the applications and patents that cite a particular subject among the full corpus of backwards citations.

Why are Patents Cited

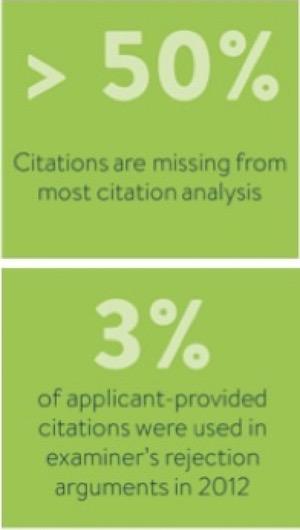

Patents are cited for two principle reasons. First, backward citations provide examples of the existing related art. In the case of applicant-provided IDS citations, the citations let the examiner know that the art was considered and the claims were carefully crafted around the prior art. In 2012, only 3% of applicant-provided citations were used in an examiner’s rejection argument. Similarly, examiners cite patents and applications as examples of the general prior art without necessarily being blocking prior art. But more importantly, examiners cite patents and applications as blocking subjects in their rejection arguments for either novelty (a 102 rejection) or obviousness (a 103 rejection).

Citation Completeness

Citation analysis is usually done with at least half the citations not recognized by the analyst, and if you are looking for important citations, most are not found on the front page of the patent. Even worse, on many newer patents, 100% of citations may not be recognized. Remember, applicants and examiners can cite either a granted patent or a published application. As it turns out, examiners cite applications far more often than they cite patents. The reason for this is because of temporal co-pendency, and the phenomenon of multiple-discovery, but more on that below.

Citation analysis is usually done with at least half the citations not recognized by the analyst, and if you are looking for important citations, most are not found on the front page of the patent. Even worse, on many newer patents, 100% of citations may not be recognized. Remember, applicants and examiners can cite either a granted patent or a published application. As it turns out, examiners cite applications far more often than they cite patents. The reason for this is because of temporal co-pendency, and the phenomenon of multiple-discovery, but more on that below.

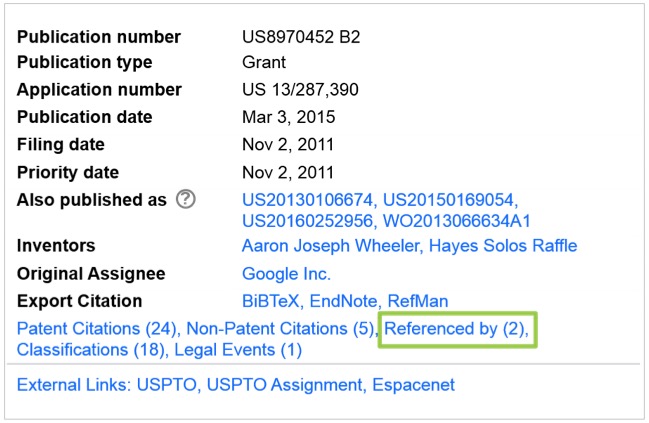

As an example, take Patent US 8,970,452 shown below. Notice how Google Patents (and likely all other reporting services), reports only two citations to the document.

While this is technically true, it is not the full story by a wide margin because the invention as a whole is not considered in Google’s analysis. The “patent” is a combination of both the patent and the parent application. After all, even if the claims change in the cited document during prosecution, the specification/description remains the same, and when examiners cite documents to build rejection arguments, they cite the specification of your patent or application, and not the claims.

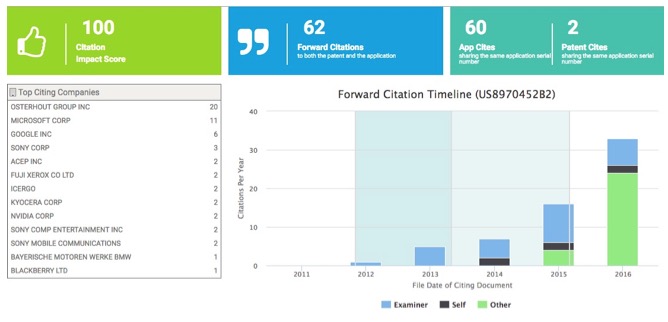

Let’s look at the same invention from a wider perspective.

The analysis above shows that the patent and its parent application received 62, not 2 forward citations. You cannot possibly evaluate the patent’s citation profile without the forward citations to the parent application. Notice the two blue plot bands behind the bar chart. The timeline illustrates when the application was filed, when the app published, and when the patent granted. This application was cited 29 times even before the patent granted which were not reported by any traditional citation services like Google Patents and others. Patents in the first darker blue plot-band, are from applications filed prior to application publication date, and they were invisible and thus unavailable to the citing applicant. This means that the citing applicant filed their application before they could have known about the possible prior art lurking in any of these co-pending cited documents. As a result, citations in the first plot band can only be from examiners, or in some cases self-citations—because they are hidden from everybody else.

This particular analysis also scores the citation profile of the patent at 100! This algorithm recognizes the age of the patent, the number of citations by examiners, self and other applicants, and the occurrence of co-pending blind citations (in the blue plot bands). The result is a score of 100, or in the algorithmic judgment, this patent is a top one percenter from a citation strength perspective.

If you only look at citations to the patent itself, you would never realize how strong the citation profile actually is, and how it may lead to infringing competitors.

If you only look at citations to the patent itself, you would never realize how strong the citation profile actually is, and how it may lead to infringing competitors.

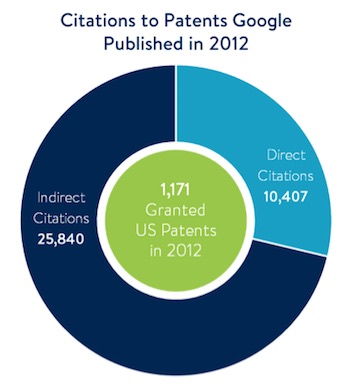

The graphic above shows the 1,171 organically developed patents in Google’s patents that were published in 2012. As of this writing there have been 10,407 forward citations directly to those patents, but even more interesting there were almost 25,840 additional citations to the corresponding parent applications. And it’s these 25,840 citations that are cited by the examiners, and cited in rejection arguments against Google’s competitors.

Multiple-Discovery of Patent Inventions

To fully grasp these concepts, you should also be familiar with the idea of multiple-discovery.

Ever notice how innovation occurs when it is ready to be invented? Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz independently invented calculus in the mid-17th century, Polio vaccine was invented simultaneously by Hilary Koprowski, Jonas Salk, and Albert Sabin; The integrated circuit was developed independently by Jack Kilby in 1958, and half a year later by Robert Noyce; the “Turing Machine” (modern computer) was proposed by Alan Turing, but also independently by Emil Post, both in 1936; and the list goes on. Among historians and sociologists, the concept is called “multiple-discovery.” One quick Google search will bear out the sociological and scientific reasons for multiple-discovery, and you’ll easily find many lists displaying hundreds of co-discovered, and co-invented technologies.

The same is true for every invention in your patent portfolio. Prior art, or multiple-discovered prior art is more likely to be found in co-pending applications—that is patents that were filed within a year or two of your filing or priority date. An artifact of the global patent system is that co-pending art is also invisible until an application is published—so you and your competitors don’t know what has been simultaneously invented until 18 months after the patent is filed and the application publishes.

Examiners recognize the important nature of multiple-discovery, and as a result tend to research prior art among co-pending applications, and more importantly they base more rejection arguments on co-pending art, than non-co-pending patents.

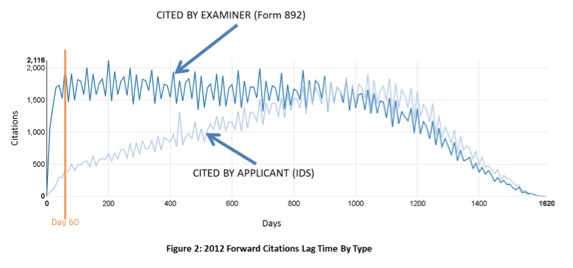

The figure above shows the time gap between the publication date of a new document, which includes either a published application, or a previously unpublished patent (Kind Code type A1, or B1, but NOT B2s) from a sample set of all documents published in 2012, and the date at which it receives its first citation.

Notice how examiners immediately find and cite the newly published art. In 2012, roughly two thousand citations were made by examiners within 60 days of publication, and only four hundred citations were made by IDS in the same period. It takes almost three years before the number of citations from IDS citations (applicant-supplied) matches those from examiners.

We argue that the reasons for this are twofold. First, examiners are more in-tune to co-pending art, and look for prior art where they know they are likely to find it. But maybe more importantly is the time lag advantage that examiners have. On average, examiners get to consider 18 months of publications that was invisible to the applicant.

The bottom line is that the important blocking citations, those used in rejection arguments, tend to come from co-pending prior art due to the phenomenon of multiple-discovery, and they are cited by examiners, and used in their rejection arguments far more frequently.

Now let’s look at the citation landscape, starting with the IDS. An IDS is typically submitted before the first office action, but can be submitted afterward with a fee. In 2014 the average IDS was submitted 484 days after the application file date. Sometimes one becomes aware of relevant art afterwards and submits more than one IDS. The breakout in 2014 was:

- 77% of applicants submitted one IDS

- 18% submitted a second IDS

- 4% submitted a third IDS

It is interesting to note that the highest number of IDS’s filed for 2014: a thirteenth submission for application by Microsoft 14/318,380!

Though there is benefit of submitting as complete a list of art as possible on an IDS, it can become an issue if the applicant is believed to be burying actual prior art in a long list, hoping it does not get noticed. A long list does not necessarily mean that, but might be questioned. As an extreme example, a recent submission for application 14/298,725 contained a 479-page IDS with 3,736 citations submitted citing patents dated as far back as 1925. Really long IDSes tend to be submitted in the pharmaceutical or medical arts industries.

One might wonder if submitting the IDS then causes the art listed to be cited against one’s own application. It can and does happen, but is rare: in 2014, only .3% of IDS provided citations were further cited in a Novelty (102) rejections against the submitter, and another 2.7% in Obviousness (103) arguments. So you could say that applicant provided citations have relative little relevance to your citation analysis.

Although it may be academically interesting to learn these trends, and if you like nerdy academic analyses, then you probably enjoyed it for knowledge sake. But using these data for competitive advantage will help keep ahead of your competition.

How to Use Expanded and Timely Citation Data

If you do plan to use forward citation data, having complete and current data allows you to learn market details that are otherwise invisible to you, such as:

- If a competitor’s product development plans are similar to yours

- Filing cited inventions that may not be claimed in your patents via the continuation process

- If a technology sector you are interested in is embryonic, mature, on the rise, or aging into a condition wherein interest is drying up

- If you are more or less active in the sector than others

With up-to-date and accurate citation data, you get insight to take actions, including:

- Steer your development plans to meet a competitor head on, or put your investment resources where your competitors largely are not

- Identify potential infringement and licensing opportunities

- Decide if the protected technology has lost its value, especially future value, so consider not paying the renewal fees

- Check that you are most active in the areas where your present products and future products need protection

- Watch for new entrants into your technical space

- Establish that a competitor is aware of your technology

Conclusion:

Technology moves quickly. By the time you notice a citation, the technology may already be mature or replaced by something else. Avoid stale sample data –better to know others have cited your IP right away instead of a year or more later. Applications that went abandoned might be more important to know about than those that issued, all having the presumption of validity over your IP.

Most people reading this article are routinely using forward citation data. However, to truly understand your forward citations and leverage the knowledge contained therein, you need better raw material, data that is three times more complete, weeks old instead of quarters or sometimes years old, and with the most important citations. Solutions are becoming available that open the door to the broader set of data, giving you the insight you need to take appropriate action.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

6 comments so far.

Paul F. Morgan

January 3, 2017 10:47 amAngry Dude, one good reason to cite a published application rather than the issued patent is because of its earlier statutory bar publication date, especially against pre-AIA applications.

Paul F. Morgan

January 3, 2017 10:44 amCounting the number of times a patent is cited in later patents as a measure of its importance or value has been sold as a valuable tool for years now. But I have yet to see any proof of its validity, and there are good reasons to doubt it. Patents are cited in later patents for their detailed specification disclosures, not for their claim breadth. Often later-filed improvement patents have much more detailed specifications than the earlier “pioneer” patent with the most valuable claims.

PS DIP

January 3, 2017 10:22 am@3 – Eric – Apply Hanlon’s razor… “Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.”

The internal systems of the USPTO are antiquated and were created before US PG-Pubs came into existence. Most reliable patent search / analysis / valuation engines use “family” based data so that citations to each and every member of a family may be considered and given appropriate weight. (We patent data nerds have been dealing with this stuff for quite awhile…)

Eric Berend

January 3, 2017 09:59 am@#2., ‘PS DIP’:

So: for mere convenience’s sake, obfuscation is normalized; and the inventor-applicants remain at a distinct disadvantage of, at the least, enormous inefficiency.

‘Big Tech’ data-crunching techniques have advanced to the point where this ‘problem’ should have a more convenient solution than manual text searching and matching. Interesting that with such a push a business in general by those entities for investment in “Big Data”, there seems to be little, where it would erode wealthy infringers’ advantage in this part of the process.

PS DIP

January 3, 2017 06:47 amIt’s much more convenient to cite a PG-Pub because the Paragraphs are all numbered and match up to the text / key word search system. It’s a royal pain to find the correct Column / Line in the issued Patent, especially if it has a lengthy specification….

angry dude

January 2, 2017 09:16 amMy published US patent application was cited twice as many times as the resulting patent – years after patent was granted

Most of citations are by different PTO examiners

Why can’t at least PTO cite an issued patent instead of its parent application ? They are all linked together in their system and this process can be easily automated