The late Justice Scalia once said that he generally did “not like patent cases.” It is all but certain that his vacancy will soon be filled by the conservative Judge Neil Gorsuch. Empirical evidence on Supreme Court decisions show that the more conservative a Justice is, the more likely he or she is to vote in favor of recognizing and enforcing rights to intellectual property.[i] However, for the reasons explained below, I believe that on his own, Gorsuch’s joining the Court may at best have marginal effect on the Court’s trajectory in patent law doctrines. It is important to explore this in the context of the historical trends of Supreme Court jurisprudence in patent law.

The late Justice Scalia once said that he generally did “not like patent cases.” It is all but certain that his vacancy will soon be filled by the conservative Judge Neil Gorsuch. Empirical evidence on Supreme Court decisions show that the more conservative a Justice is, the more likely he or she is to vote in favor of recognizing and enforcing rights to intellectual property.[i] However, for the reasons explained below, I believe that on his own, Gorsuch’s joining the Court may at best have marginal effect on the Court’s trajectory in patent law doctrines. It is important to explore this in the context of the historical trends of Supreme Court jurisprudence in patent law.

A common refrain in the realm of patent commentary, blogs, and symposia, is to beleaguer the Supreme Court to keep its hands off the patent law. This exhortation is not new. The predecessor to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, the national appeals court for patents, had on occasion viewed Supreme Court review as detrimental because of the risk that the Justices would misunderstand and misapply patent doctrine.[ii] Commentators have since criticized the Supreme Court’s frequent failure to understand the patent law and craft effective doctrine.[iii] Donald Chisum, author of the leading treatise on U.S. patent law, has concluded that “the Justices seem to treat patent cases as second class citizens and write opinions that read as though they were dictated while standing waiting for the elevator.”[iv]

Cause for some of this criticism can be traced to at least three factors. The first is the political preferences and attitudes held by the Justices.[v] The second is the Justices’ lack of science and technology experience, never having been closely involved in discovery and invention. Lending support for this notion is the fact that Justices are nearly twice as likely to decide in favor of copyright owners as in favor of patent owners.[vi] All Justices are accomplished authors; none were inventors, scientists or entrepreneurs. With this background, Justices may simply be more sympathetic to the claims of an author against a copier than they are to the claims of an inventor against a rival producer. Third is the fact that all Justices are generalists without prior patent law experience. Thus, they often seek to eliminate patent “exceptionalism,” attempting to bring patent law in conformity with general legal principles.[vii] The resulting decisions reveal the Supreme Court’s holistic outlook as a generalist court concerned with broad legal consistency rather than fidelity to patent law’s underlying specialized and unique features moored in technology research, invention, and patenting processes. Unfortunately, as shown below, the adverse effects on patent rights due to the deviant patent doctrines arising out of the Court’s decisions far exceed the benefits of assimilation and conformity of the patent law with the general law.

Recently, starting with the Festo decision in 2002,[viii] the Supreme Court has decided a sequence of cases that have incrementally weakened the force of patent rights. The case in Festo goes to the heart of patent law by limiting the doctrine of equivalents whenever the applicant made a narrowing amendment to the claims in prosecution at the Patent Office. The impact is most severe in the biotechnology field: because thousands of different analogs of a protein could be made by substituting a single amino acid, potential infringers would easily circumvent claims to a specific protein by substituting amino acids, thus placing an impossible burden on the applicant to specifically disclose and claim all potential analogs. Adverse consequences of Festo’s limit on the use of the doctrine of equivalents are not only the narrower construction of claims in litigation; patent applicants now face the dilemma at the Patent Office when attempting to avoid amendments to the claims in order to preserve the protection of the doctrine of equivalence, only to increase the risk that the claims may later be found invalid.

With the landmark 2006 decision in eBay,[ix] the Supreme Court has fundamentally demoted the meaning of the constitutional term “securing … the exclusive right” for virtually all patentees that are non-practicing entities. The result of eBay for such patentees is the effective loss of injunctive relief – property rules are trumped by liability rules, in which the patentee receives monetary damages from the infringer, effectively as a compulsory license.

In 2007, the Supreme Court made it easier to find a patent invalid for obviousness under 35 U.S.C. §103. In KSR,[x] the Court rejected the Federal Circuit’s “rigorous approach” of requiring at least one of the established indicia of obviousness—teaching, suggestions or motivation (TSM) to combine known elements. The Supreme Court noted that TSM is but one of several factors that may be considered in evaluating whether a claimed combination is obvious. The Court removed the clarity of TSM by injecting other “several factors” with the circular definitions of “common sense” and “whether it would be obvious to try” – criteria that are prone to hind-sight subjective second-guessing of obviousness. Following this decision, unbound by any objective standard, judges and patent examiners would proclaim obviousness by “common sense” and by circular arguments that the combination is “obvious” because it is “obvious to try.” As a result, many more patents were found invalid for obviousness and many more patent applications failed to overcome rejections based on obviousness.

The Supreme Court has issued other decisions that have incrementally weakened the force of patent rights in other ways. These include Quanta, [xi] upholding patent exhaustion doctrine and expanding scope of implied licenses, and MedImmune[xii] which expanded the circumstances under which a patent licensee may seek declaratory judgment that the licensed patent is invalid. Most dramatically, the Court issued decisions between 2012 and 2014 that cast serious doubt on the validity of hundreds of thousands of biotechnology, medical diagnostics, software, and business method patents in force.[xiii]

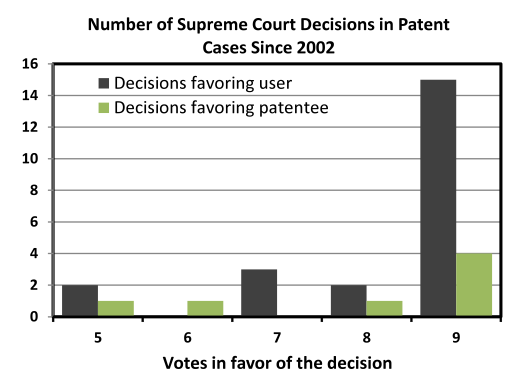

The accompanying table above summarizes all patent law decisions issued by the Supreme Court since the eBay decision in 2002. It includes the Justices vote count and an indication whether the decision involved an interpretation of the law that tends to favor and enhance patent rights or whether it favors the user, an alleged infringer or licensee.[xiv] The table indicates that Supreme Court decisions that weakened patent rights were 3.3 times more frequent than those favoring patent rights.

Nothing like the Supreme Court’s problematic jurisprudence on patent-eligible subject matter (the definition of the types of inventions that are protectable under patent law) demonstrates the urgent need to inject some serious technical patent law expertise to the Court. The 1952 Patent Act enumerates the types of patent-eligible inventions by conferring patent protection for “[w]hoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof” subject to other patentability requirements. 35 U.S.C. § 101 (emphasis added). However, the Supreme Court has long redefined the four enumerated statutory categories by barring patent protection for certain types of inventions or discoveries: “Laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas are not patentable.”[xv] Thus, for patent-eligibility of inventions involving elements from any of the three judge-made categories, the Court requires that the claims must be directed to an “inventive concept,”[xvi] or “something more.”[xvii] By this, the Court conflates subject matter eligibility in § 101 with the patentability requirements for novelty and non-obviousness in §§ 102, 103. Moreover, for decades, the Court consistently declined to define the term “abstract idea” whenever the opportunity to do so arose.[xviii]

The spectacular failure of the Supreme Court to craft effective patent law doctrine in the most critical gateway to innovation – the type of subject matter eligible for patent protection – has been criticized by key thought leaders in patent law. In recent oral remarks, the former chief judge of the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit explained the problem created by the Justices:

How do you define an abstract idea? … What limitations add significantly more to a claim that has in it one of these implied exceptions that the Supreme Court has pulled out of nowhere. It’s not in the Patent Act, the four categories. Nothing in [the statute exists] by way of exceptions. Certainly nothing in there about abstract ideas, laws of nature, natural phenomena, etc. They just made it up.[xix]

A technology field that is highly susceptible to the confusion and mischief arising out of the Justices’ inability to effectively address substantive patent-eligibility law involves computer-implemented inventions and software related patents. The Alice case involved such claims and when the question before the Supreme Court arose, whether “claims to computer-implemented inventions – including claims to systems and machines, processes, and items of manufacture – are directed to patent-eligible subject matter,” Donald Chisum wrote:

That this question warrants Supreme Court deliberation in 2013 is startling and disgraceful. How can such uncertainty exist in the 21st century about so basic a question as the patentability of computer software? Computers, software, and disputes about intellectual property protection for programming have been around since the 1960s. The statute at issue (Section 101) is unchanged since 1952.

The responsibility lies squarely at the feet of the Supreme Court. Its confusing statements about the patenting of “abstract ideas” have trickled down to the lower courts, understandably causing disagreements among judges. Regrettably, the result is one of the most serious diseases that can infect the legal system: similar cases are decided differently based solely on the identities of the judges.” [xx]

The dearth in understanding technologies and related invention processes and the lack of prior expertise in patent law pertains to Justices across the political spectrum. Patent law raises questions that have the potential to divide conservatives and liberals alike, as it pits principles of liberty and property against one another. For example, the pillars of the recent problematic jurisprudence on patent-eligibility were authored by liberal Justice Breyer (Mayo v. Prometheus) and by conservative Justice Thomas (Alice v CLS Bank).

Computer-related inventions and software products powered the American economy and work force as it transitioned from automobiles, textiles, consumer products, steel and other industries that went offshore or simply changed due to technology or regulation. This is extremely significant because estimates from the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers show that 44% of all U.S. patents in force are, in some way or another, software-related patents.[xxi]

Patent-eligibility rulings that do not cohere with technological realities and modern scientific thinking can only distort the development of the patent law. Patent protection for the most advanced technologies is denied, thereby suppressing incentives for leading-edge domestic R&D investments that can bring back American jobs. In recent testimony before Congress, Robert Stoll, the former Commissioner for Patents at the U.S. Patent Office explained that America is now

the narrowest subject matter patent-eligible country in the world. The effects of these decisions as they are being applied by the lower courts are limiting the availability of patents in core technologies—areas of computer implemented programs, diagnostic methods and personalized medicine—and thereby limiting the ability of innovators to provide value to consumers, build their businesses, and grow. These cutting edge fields are the very technologies in which the United States leads the world. In Europe, claims must have “technical character” and in China claims must have a “technical feature distinctive from the prior arts”. So these other countries have broader subject matter eligibility than we do! [xxii]

Finally, the eroding strength of patent rights is due not only to the decisions the Supreme Court has made or affirmed, but also to those it declined to make. A decision to deny certiorari results in a de-facto affirmance of a Federal Circuit decision, which, in some cases can be highly detrimental to patent rights. For example, in two recent landmark decisions, the Federal Circuit held that patent rights are not “private rights” (rights which arise in exchange for the inventor’s private trade secret rights when those are disclosed in a patent) but are rather “public rights,” i.e., rights that are created by the federal government. Thus the Federal Circuit held that Congress can delegate patent validity adjudications to administrative tribunals having neither Article III constitutional protections for patentees nor the right to a jury trial under the Seventh Amendment. The Supreme Court denied both petitions for certiorari,[xxiii] essentially opening the door for Congress to delegate all adjudications of patent validity from Article III courts to an administrative patent board at the U.S. Patent Office.

The bar chart below breaks down the decisions listed in the table above by the Justices’ votes (excluding neutral decisions), showing that only a small fraction were closely decides by a majority of 5 votes.

It therefore appears that patent decisions will seldom be close decisions in the future. Thus, unless would-be Justice Neil Gorsuch demonstrates extraordinary persuasive effect on his future colleagues, even if he should arrive at opinions favorable to patentees, he would be unlikely to tip many decisions of the Court in favor of patent holders. Inevitably, it would still be up to Congress to legislatively undo the Supreme Court’s harm to American patent rights.

_______________

Notes

[i] M. Sag, T. Jacobi, and M. Sytch. “Ideology and Exceptionalism in Intellectual Property: An Empirical Study.” 97 California Law Review, 801-56 (2009).

[ii] See, e.g., Application of Bergy, 596 F.2d 952, 966 (C.C.P.A. 1979), aff’d, 447 U.S. 303 (1980) (The Supreme Court’s decision in Parker v. Flook, 437 U.S. 584 (1978) “may have unintended impact in putting an untimely and unjustifiable end” to long-standing propositions of patent law. “The potential for great harm to the incentives of the patent system is apparent.”).

[iii] Donald S. Chisum, The Supreme Court and Patent Law: Does Shallow Reasoning Lead to Thin Law?, 3 Marq. Intell. Prop. L. Rev. 1, 4 (1999) (showing that quality of reasoning by the Supreme Court is often weak, illogical, ambiguous, and inconsistent); John F. Duffy, The Festo Decision and the Return of the Supreme Court to the Bar of Patents, 2002 Sup. Ct. Rev. 273, 329–32 (2002) (inventions often entail incremental improvements: the details of such patent cases are likely to be difficult for generalist judges to understand, thus likely to seem so minor as to not be worth the effort to understand); John M. Golden, The Supreme Court as “Prime Percolator”: A Prescription for Appellate Review of Questions in Patent Law, 56 UCLA L. Rev. 657, 672-700 (2009) (Justices have little to contribute as generalists after all, and the Supreme Court will, in fact, do worse in developing substantive patent law than the semispecialized Federal Circuit).

[iv] Chisum, supra note 2, at 16.

[v] Sag et al. (2009) Supra note 1; See also Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., The Common Law, 1, Boston: Little, Brown, & Co. (1881) (“The life of the law has not been logic: it has been experience. The felt necessities of the time, the prevalent moral and political theories, intuitions of public policy, avowed or unconscious, even the prejudices which judges share with their fellow-men, have had a good deal more to do than the syllogism in determining the rules by which men should be governed.”)

[vi] Sag et al. (2009) Supra note 1 at 841.

[vii] Peter Lee, The Supreme Assimilation of Patent Law. 114 Michigan Law Review, 1413 (2016).

[viii] Festo Corp. v. Shoketsu Co., Ltd., 535 U.S. 722 (2002).

[ix] eBay, Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C., 547 U.S. 388 (2006) (holding that, even if patent is found valid and infringed, injunctive relief against infringer not granted unless equitable four-factor test is met).

[x] KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex, Inc., 550 U.S. 398 (2007).

[xi] Quanta Computer, Inc. v. LG Elecs., Inc., 553 U.S. 617 (2008).

[xii] MedImmune, Inc. v. Genentech, Inc., 549 U.S. 118 (2007).

[xiii] On biotechnology patents, see Ass’n for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc., 133 S. Ct. 2107 (2013) (denying patent-eligibility of certain isolated genetic sequences even though isolation does not occur naturally); on medical diagnostic patents, see Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs., Inc., 132 S. Ct. 1289 (2012) (holding that claims directed to administering and determining an effective level of certain drugs in the treatment of autoimmune diseases were patent-ineligible); on software and business method patents, see Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int’l, 134 S. Ct. 2347 (2014) (holding that the claims were directed to an “abstract idea” without “something more.”).

[xiv] “P” means the decision results in an interpretation of the law that tends to favor the patentee in patent infringement suits (even if the patentee may not have prevailed in that particular suit). “D” means the decision results in an interpretation of the law that tends to favor the alleged infringer or licensee (even if they may not have prevailed in that particular suit). “N” means the decision resulted in an interpretation of the law that does not clearly favor either side.

[xv] Alice, supra note, 10 at 2354 (citation omitted).

[xvi] Mayo, supra note 10, at 1294.

[xvii] Alice, supra note 10, at 2350 (“in applying the § 101 exception, this Court must distinguish patents that claim the building blocks of human ingenuity, which are ineligible for patent protection, from those that integrate the building blocks into something more, thereby transforming them into a patent-eligible invention.”) (citing Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., 132 S.Ct. 1289, 1303 (2012)).

[xviii] See, e.g., Alice, supra note 10, at 2357 (“In any event, we need not labor to delimit the precise contours of the ‘abstract ideas’ category in this case.”).

[xix] Hon. Paul R. Michel, Judicial Litigation Reforms Make Comprehensive Patent Legislation Unnecessary as Well as Counterproductive, 14 Northwestern Journal of Technology and Intellectual Property, 131,136-137 (2016) (emphasis added).

[xx] Donald S. Chisum, Patents on Computer-Implemented Methods and Systems: The Supreme Court Grants Review (CLS Bank) Background Developments and Comments, Chisum Patent Academy (December 10, 2013).

[xxi] IEEE-USA Amicus Curiae brief in the U.S. Supreme Court case CLS v. Alice, (January 28, 2014) (Appendix estimating that as of 2012, nearly 1 million software-related patents were in force, a substantial fraction of all 2.23 million utility patents in force).

[xxii] Testimony of Robert L. Stoll, Former Commissioner of Patents at the USPTO, Before the Senate Committee on Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 114th Congress, (February 25, 2016). See hearing video at 1:21:10 – 1:22:35.

[xxiii] Cert. denied: MCM Portfolio LLC v. Hewlett-Packard Co., No. 15-1330, 2016 WL 1724103, (U.S. Oct. 11, 2016); Cooper v. Square, Inc., No. 16-76, 2016 WL 3856113 (U.S. Nov. 14, 2016).

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

27 comments so far.

Anon

March 7, 2017 09:48 pmNight Writer,

You are incorrect, and history alone provides plenty of examples (just think Dred Scott for starters).

Night Writer

March 7, 2017 04:00 pm>Can the Supreme Court’s erosion of patent rights be reversed?

No.

Anon

March 6, 2017 10:23 pmStill waiting, Mr. Heller.

Ron Katznelson

March 6, 2017 09:20 pmAs my article explained, the SCOTUS’ punt on a key property right question is troubling. It could have corrected the Federal Circuit’s long-held error; patents are property and IPRs adjudicate private rights: in a proceeding in which claims are cancelled, the patent bargain is undone without restoring to the inventor his/her private right of trade secrecy. The petitioner receives private benefit – the right to exploit the inventor’s published description of an invention that would otherwise be protected by private rights of secrecy, and the inventor incurs a net loss of that private right because the loss of secrecy (by publication of the patent) is irreversible. It is this economic transfer of a private right to the petitioner at the expense of a net loss to the inventor’s private right that is at the heart of IPR adjudications.

See my full legal and historic analysis in the Amicus Brief I authored on behalf of IEEE-USA and filed in support of the MCM’s cert petition at http://bit.ly/Amicus-MCM.

step back

March 6, 2017 06:52 pmDoes this mean that Thomas actually cares about property rights?

https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/16pdf/16-122_1b7d.pdf

Night Writer

March 5, 2017 01:45 pm@12 Ed the Ned: You have stated many times that no software is patentable unless it is burned into a ROM.

angry dude

March 4, 2017 06:55 pmstep back @19

No, I’m not stuck in this world and don’t need anti-gravity for that

I invent things for Virtual Reality nowadays – literally spend some time out of this sorry world

When I’m done I will completely disappear into virtual worlds and you won’t see me again 🙂

step back

March 4, 2017 04:05 pmStay angry my friend:

https://cdn.meme.am/cache/instances/folder504/500x/66432504.jpg

step back

March 4, 2017 04:00 pm@18 angry:

Both Left and Right have contempt for patents held by non-corporate or small corporate owners.

Probably for different reasons and maybe those are worth exploring.

On the High Court (SCOTUS) you have Breyer J. of the Left making fun of computer related inventions by calling forth the spirits of King Tut and his abacus man.

On the far right you have Scalia/Thomas calling it all gobbledygook and comparing it to something understood from the dawn of time (from the fundamental truths seeking times of the 1850’s).

In the middle you have Kennedy J. believing that an “idea” is something you hand over to any arbitrary 2nd year engineering student during a chance meeting at a Silicon Valley coffee shop and then that student takes care of the geek details by “coding” a single generic computer over weekend’s last gleaming.

In other words, for their respective different reasons, the Left, the Right and the Middle all disrespect the American inventor and hi/her right to secure exclusive rights for his/her discoveries.

Obama only pretended to be pro-science. He really did not understand it. That is evident from his charging good ‘ole Joe Biden to launch a “Moonshot” to cure cancer for once and for good. It is also evident from whom Obama appointed to be in charge of the USPTO and from his signing the AIA into law.

We’re stuck on this one planet of the primates until you invent and reveal your anti-gravity machine. 🙂

angry dude

March 4, 2017 12:32 pmstep back @17

Dude,

wtf are you talking about ???

Trump’s administration is anti-science – they don’t believe in climate change

Obama’s administration was pro-science but still killed the golden goose – US patent system

Screw them all

Find me another planet

step back

March 4, 2017 12:19 pmTo reverse at the SCOTUS,

first we must get at the underlying resurgence in anti-science sentiment within the general population and among our its-a-hoax politicians.

http://www.betterworldclub.com/blog/2014/05/02/epas-mccarthy-slams-the-agencys-anti-science-critics-1/

angry dude

March 3, 2017 09:19 pmEric @13

Well said but futile…

After EBay I knew immediately that we were screwed

I’s been a long time since any independent inventor in tech space made money in pure patent enforcement

The last example I can remember is Townshend (56K modem) and that was in late 90s…

The doc said ‘to the morgue’, to the morgue it is!

Independent Inventor

March 3, 2017 08:33 pmSuperb, Eric, simply superb.

Gene — this is worthy of its own, standalone article. Hope you’ll consider making it so.

Anon

March 3, 2017 08:24 pmMr. Heller @ 12,

I will kindly refrain from entertaining your attempted deflection, and would instead appreciate a more direct response.

Eric Berend

March 3, 2017 06:53 pmThank you very much, Ron. This inventor appreciates being able to have guidance as to the strategic view of the legal ‘lay of the land’. Unfortunately, in terms of the foundation basis of separation-of-powers, the situation as you described it, is very similar as what it appears, to me.

You articulate the issue simply and correctly, in explicating the trade now being one of private rights of trade secret for supposedly public rights of now-feckless and inventor-antagonistic establishment. Patlex Corp. v. Mossinghoff was an abomination; that Judge Newman has been fruitlessly chasing down for over 30 years. No matter how “patent friendly” nor patentee oblivious or hostile she may have been since that time, there can be no placing the genie back into that bottle – without the intervention of the U.S. Congress.

As an inventor, whose father was also an inventor, that brought a “Prius” design in prototype, to the New York Int’l Auto Show in 1961 (and now found in a McLaren F1 doing 900+ HP near you), I find the current milieu to be an outrage, plain and simple.

The current-day anti-patent movement is, fundamentally, a criminal and civil “RICO” racket, with the specific purpose of plundering the intellectual property of U.S. inventors; for the unjust enrichment of “Big Tech” and the gold-plated ‘Silicon Valley Pirates’. The criminal part, is founded in the illicit influences against the public interest; in which dozens of a certain specific corporation’s officials also took positions in the U.S. Federal government; influencing and directing policy and appointment of positions in the Judicial Branch; to an unprecedented proportion of overall Federal positions for any one interest in all U.S. history; and particularly, in policy making positions.

At this advanced point of its operation, how can this not meet the legally settled definitions of civil and criminal conspiracy?

What – is this ‘forest’ so large, that nearly everyone concerned, became ‘lost in the trees’? Where is the strategic vision, or even, a merely partially adequate scope of comprehension?

As an inventor, my role is to invent. I have at least six potential patents for new apparatuses in several different fields; all physically founded and not process-based or oriented (i.e., including software, of course). All, are jeopardized in their manifestation, if I dare take on the presently absurd risk of disclosure in the process of U.S. patent prosecution.

One of the MOST essential aspects heretofore obscured in this debate, is the actual loss of public benefit, to having the inventor drive the adoption of the invention technology. This effect and potential in the public interest, cannot be overstated enough; especially, at a time of fundamental property rights degradation, as this.

Call it, for now and for want of a more cogent and less banal exemplar, the “Steve Jobs effect”. When the engineer or designer is involved with ‘skin in the game’ in the actual implementation and market adoption of a particular technology; then, there is the greatest chance of the best and highest value outcomes, in both the public and private interests.

When entrenched and not subject to such potential of competition, the benefits of adoption of competing and disruptive new technologies; is left to established corporations and markets; which have amply demonstrated, time and time again, that this public interest becomes derogated, and the technology’s adoption, hampered, degraded or eliminated entirely. What force then, will serve to advance the U.S. public interest in the benefits of new technology?

Richochet Network – ever heard of it? In 1998 – 1999, they provisioned 120K wireless Internet access, open sky; in at least 21 metro U.S. areas and expanding. Then, it was bought out, and disappeared. Now, some EIGHTEEN YEARS LATER, do we yet, have ANYTHING even CLOSE? NO. *[1]

It’s ISDN all over again – hold it back from the public, dole out watered down versions presented in extortionist nosebleed pricing to selected corporate customers for TWENTY YEARS, then watch it finally get sidetracked by the rise of the Internet based upon TCP/IP and IEEE Ethernet standards adoption.

And now, at this point? The so-called “disruptive” technology implementation was squashed. The public benefit was wholly thwarted: the technology never appeared again. But the “Big Telco” cabal got to monopolistically fluff up its stock prices and apparent profits, at everyone else’s expense.

Yet, some would dare conflate patents with actual monopolies. Patents are, in fact, a potent monopoly-busting tool! How else, shall ‘mature’, fully consolidated industries become challenged by competition? Why else, would huge, “1er%” monopolists, seek to destroy or neutralize these instruments of property protection? The patent practitioner community has been thrown back on its heels for so long now, in this mendacious, evil attack, that opportunities to demonstrate a superior and much more truthful narrative, have gone by the wayside.

I am gifted in strategic analysis; however, from my viewpoint, that is a ‘fight off the alligators’ function – it distracts from and consumes time and resources better directed towards the ‘drain the swamp’ of inventing. So, isn’t about time that such an admonishment, is leveled at the patent practitioner and political communities?

Time to wake up, put some pepper in your big-boy pants, and put them on. This ship is going down, and it awaits your earnest participation in the fight. We’ve been getting our clock cleaned now by liars and demagogues for years, and it’s partly because the enemy took the kid gloves off and got down-and-dirty – and this side of the issue did NOT – so far, the response of the patent practitioner communities of inventors and attorneys; on those levels of society; has been, shall we say, quite lacking. This conflict will not be won or at the least, adequately defended, solely through genteel collegial comportment.

*[1] ”With capital market conditions the way they are, I think it’s really unlikely,” said Scott Ellison, who is director of wireless mobile communication at the Massachusetts-based research firm IDC and works out of its New York office. ”High-speed wireless data networks are out of favor because similar services are expected from larger companies like AT&T Wireless, Cingular and Verizon.”

(New York Times, Aug. 16, 2001, “Technology” column)

Edward Heller

March 3, 2017 05:38 pmAnon, “….with your rather well known bias against software patents.” Give me an an example of a “software” patent the I am biased against.

Anon

March 3, 2017 04:48 pmWhile I am sure that a certain segment of the population would be enthralled with a series dealing with patent law issues, I would settle for such issues to be dealt with in the blogosphere in an inte11igent and inte11ectually honest manner.

The re-animation (or attempts thereof) of the Mental Steps Doctrine and the (purposeful) obfuscation of machines with the human mind undergirds a HUGE element of the anti-software patent ideology.

There is a massive need for sunlight to be used and the (purposeful) misconceptions made plain and reburied once and for all.

I am sure that with your rather well known bias against software patents, that you would like to be able to make your case without depending on a decrepit and (purposefully) misconstrued doctrine. Would that be a correct presumption?

step back

March 3, 2017 04:32 pm@7 Ned

There is only one “creator” in the present universe.

The rest of us rearrange that which was made available by the creator.

Edward Heller

March 3, 2017 03:49 pmAnon, Tutorial? On Zombification? So we have half dead doctrines walking about? We need a new TV Series: The Walking Dead Doctrines starring Rick Grimes.

Anon

March 3, 2017 03:11 pmMr. Heller, perhaps you can convince the moderator at that other site to provide a tutorial on the rise, fall, and attemtped Zombification of the Mental Steps doctrine of patent law.

It is clear that the “version” being bandied about is quite disassociated from its patent law moorings.

Edward Heller

March 3, 2017 02:46 pmRon, you said, ” By this, the Court conflates subject matter eligibility in § 101 with the patentability requirements for novelty and non-obviousness in §§ 102, 103. ”

Respectfully, the court has always treated the 101 requirement of “new” differently than simply not “known.” The requirement for newness requires some creation of the inventor beyond the discovery of the product of nature or law of nature.

Regarding “abstract ideas,” based on a very fruitful discussion with Distant Perspective, I agree with him that this only effectively means “mental steps.” When the novel subject matter is an abstraction, it must be applied to transform, etc. Effectively, this test is equivalent to the MOT. The Federal Circuit decision are consistent, especially when the claimed subject matter is directed to software that improves the until of a computer or computer systems.

On IPRs and the constitution, perhaps the issue for decision by the Supreme Court should be whether the Federal Circuit was correct that Congress can, consistent with the Seventh Amendment, assign the trial of an patent validity for which there is right to a jury trial to an administrative agency where no right to a trial by jury.

step back

March 3, 2017 12:29 pmPatent cases expose a number of embarrassing attributes about we human creatures.

First we tend to be very vane. Ninety percent (90%) of us think we place in at least the top 50% of our population if not in the top 10% or 1%.

Second we are incompetently blind to almost all the things we are incompetently blind to. (How many of you are picking up the IR wavelengths now coming off your screen or hearing the ultrasonic vibrations?)

Third we crave social admiration. (Mirror mirror on the wall, who is the most admired of us all?).

Supreme Court Justices are susceptible to all these vices and succumb to them on a regular basis.

Yes. They all have very high IQ’s and are among the top 10% smartest people in our population.

But so too are all the young among our population who pursue advanced studies in the hard sciences (e.g. physics, chemistry, electronics, …). Why does it take our young ones (those with super high IQs) so many years to “get it”? Answer: because it’s hard hard stuff and our biological brains can only do so much and not much more.

If you were a Justice sitting on the SCOTUS and all your “friends” (amici curie) complemented you on how smart and clever you are and convinced you that molecular biology is no more complicated than plucking a leaf off a tree, wouldn’t you believe them?

And if some non-“friends” tried to explain to you that molecular biology is hard and that is why our high IQ youths take so long to earn their PhDs and that is why you, one of the “Supremes” may never understand it; wouldn’t you discount everything they argue?

So sure. At the end of the day all the complex stuff reduces to “generic” computers doing no more than conventional and routine operations, ones that 2nd year coders do every weekend without breaking a sweat. All those so-called smarty pants inventors out there and their devious scriveners cannot possibly be smarter than we the Supreme SCOTeti. They are merely trying to hoodwink us with their voodoo witchcraft and obfuscating language.

Aha. We can see right past them by devising a simple framework for witchcraft detection. First we dangle an oblong magic shard at the end of a string, slowly move it over the claim and give it a twirl. If it points in almost any direction but one secret one, the claim is clearly “directed to” skullduggery.

But just to be fair (because after all, our mirror tells us we are the fairest of them all) we will apply a second test. We submerge the claim in holy witch water to see if it has that elusive “something more”. You see, witches are made of wood and thus they float. Only those that have that “something more” stay under.

So after all that, why are all those cry baby inventors complaining? We have been imminently fair. After all, “we” are Supreme and in that top 1% number. Clearly they are not. Sigh.

Independent Inventor

March 2, 2017 06:40 pmThank you Ron. A most insightful and important patent treatise indeed.

Iamnotmichellelee

March 2, 2017 01:55 pmSee these two articles by Judge Michel: http://www.iam-media.com/Magazine/Issue/80/Features/The-uncertain-state-of-patent-law-10-years-into-the-Roberts-court and https://www.criterioninnovation.com/articles/understanding-the-errors-of-ebay/

Night Writer

March 2, 2017 10:31 am@1 David: I largely agree with what you said.

angry dude

March 2, 2017 10:19 amThe doc said ‘to the morgue’, to the morgue it is!

David

March 2, 2017 10:08 amAbout MCM, Cooper, and Gorsuch:

It stands to reason that if the Article III question was set in stone, the Court would not have compelled the USPTO to file a response on Monday.

Though patent decisions are often unanimous, the Article III question is not a patent case, it’s a separation of powers case. Simply, the case asks “who gets to decide?”

In Stern v Marshall (2011), the Court split 5-4, with the dissenters looking to preserve Article I courts in an advisory role.

Though questions of patent law tend to be apolitical, separation of powers determinations often track party lines.

Without Scalia, MCM and Cooper may have resulted in a 4-4 deadlock. The mere possibility would have counseled the Court against cert.

Gorsuch’s pending arrival changes that.