LinkedIn was a big brand name with a small patent portfolio – a combination that made it vulnerable to attack. In 2012, the company decided to do something about it and here is what happened. In a 4-part series, we explore the steps LinkedIn took to reduce its risk profile and how it grew its patent portfolio through a strategy of organic patent filings and targeted patent acquisitions. Our 4-part series covers the following:

Part 1: How and Why LinkedIn Learned to Love Patents

Part 2: LinkedIn’s Patent Strategy

Part 3: Assertion Risk Mitigation Opportunity Through Patent Acquisition

Part 4: A Prepared Counter-Assertion Strategy (forthcoming)

_______________

LinkedIn was a rapidly growing company with only 22 patents in its portfolio in 2012, putting itself at high risk for patent assertion. With a revenue reaching nearly $1 billion and a growth of 86%, LinkedIn knew it had to develop a patent strategy to reduce its risk profile. So what was LinkedIn’s patent strategy and how did it increase its patent filings? Let’s start at the beginning.

LinkedIn was a rapidly growing company with only 22 patents in its portfolio in 2012, putting itself at high risk for patent assertion. With a revenue reaching nearly $1 billion and a growth of 86%, LinkedIn knew it had to develop a patent strategy to reduce its risk profile. So what was LinkedIn’s patent strategy and how did it increase its patent filings? Let’s start at the beginning.

LinkedIn launched the first professional social network in May 2003. Over time, it has become highly successful and increased its revenue in 2006 by 723% to $9.8 million and then by an average of 128% each year from 2007 to 2011 (LinkedIn Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Form S-1 and 2013 SEC Form 10-K). The company went public in May 2011 and by 2012 was making around $1 billion in annual revenue and continuing to grow rapidly: revenue had increased 86% over the previous year, R&D spend had risen by 95%, and headcount was up 63% (LinkedIn 2013 SEC Form 10-K). However, at the same time, LinkedIn had only one issued US patent and 35 pending applications. Company executives recognized the exposure to corporate patent assertions, but had held off dealing with the challenge until the business had proven itself. In 2012, LinkedIn hired a small internal patent team and began working with Richardson Oliver Law Group to come up with a mitigation plan.

The opportunities for risk mitigation can be divided into two categories: increasing organic filings to address future assertion risk and patent acquisition to address present and near future risk.

Future organic filings

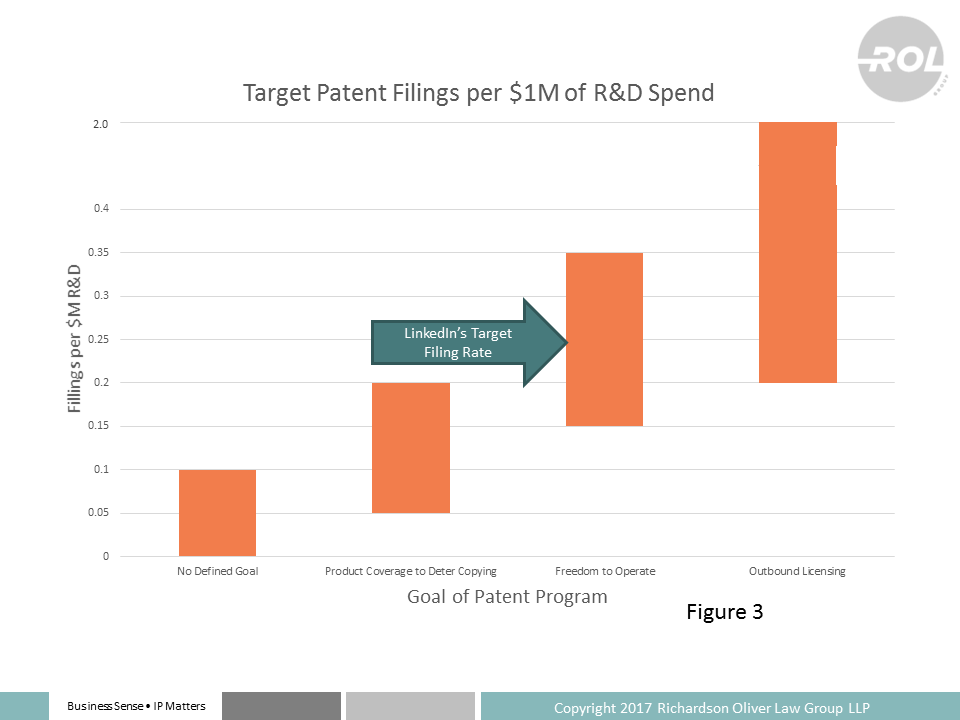

To determine a target patent filing rate, LinkedIn reviewed the goals and filing practices of other high-tech companies. A more sophisticated return on investment (ROI) analysis was not carried out at the time because LinkedIn already knew it was behind. The patent strategy team first looked at about 25 high-tech companies, analyzing their filing rates and R&D spend. R&D spend is a good proxy for how much innovation is taking place, as well as for future revenue expectations – which corporate patent asserters will target. We analyzed the companies to determine an imputed patent strategy and divided them into different bands based on the patent program’s goals (Figure 3):

- no defined strategy;

- product coverage to deter copying;

- obtaining freedom to operate; and

- outbound licensing.

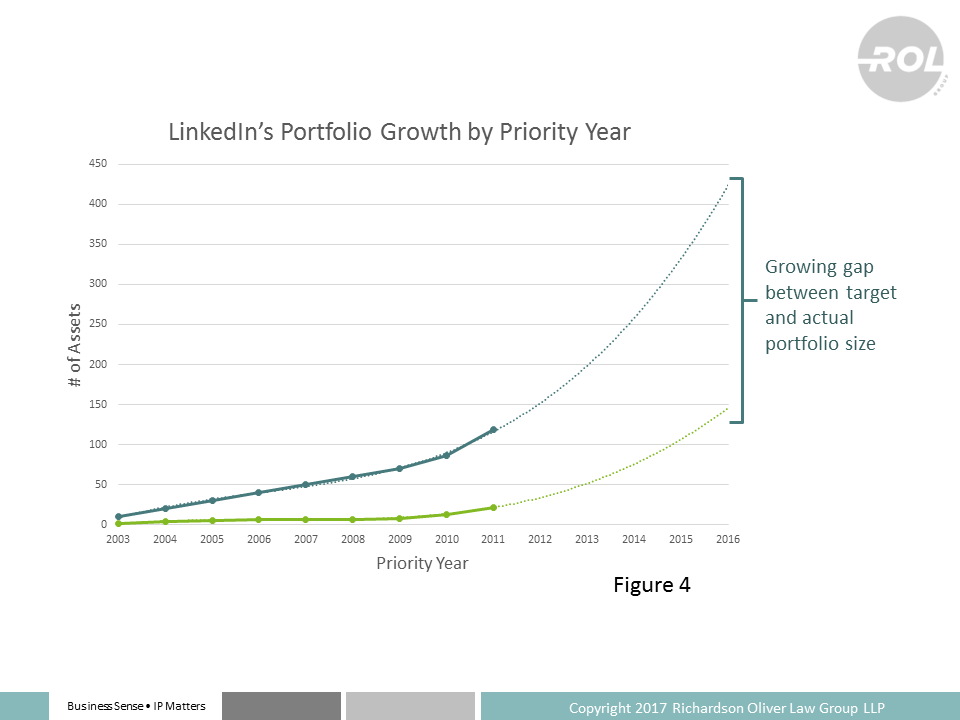

We set our goal as obtaining freedom to operate; we wanted to be able to continue to deliver products and services to our growing customer base by relying on our core technologies, while minimizing patent risk from larger patent holders. We thus set our target filing rate in the middle of that band – 0.25 patents per $1 million in R&D spend. As illustrated in Figure 4, LinkedIn’s filing rate had been below our target rate before 2001. Had it remained unchanged, the projected organic filings in 2016 would have missed the target or freedom to operate by almost 300 patents. Arguably, LinkedIn could have used a higher filing rate for the earlier years, as those years tend to produce some of the most fundamental patents. However, even without this, LinkedIn needed to catch up.

How LinkedIn increased patent filings

LinkedIn increased its organic patent filings to 0.42 filings per $1 million R&D in 2015. While this was above the 0.25 target, these additional filings helped to close the gap created by previous low rates. In order to increase the filing rate, LinkedIn needed to fundamentally shift its patent culture. Timetables and goals were discussed and set, and several targeted projects were launched.

First, invention harvesting sessions were held on a regular basis. Minimizing the impact on inventors’ time and attention was critical to the success of this program, so we gathered small groups of engineers together and reviewed their current work, captured the ideas they put forward and selected those that met the filing criteria.

Further, we benchmarked inventor incentives to better align with other social media companies.

We added a highly visible recognition component to our incentive program, which included inventor appreciation events (for example, our private movie premieres were very successful), program-branded clothing and patent cube awards – all of which were designed to reward inventors and promote the program.

In addition, we carried out education as to the size of the patent deficit problem and the plan, obtaining buy-in from the general counsel, the engineering and product teams, the finance department and the chief executive officer.

With the increased filing rate came a significantly increased budget. A well-defined plan helped clear the budget request.

Figure 5 shows the results of the efforts on filings. From 2012 to 2016, our filings increased from 20, 80, 120, 200, 300 and 330, to match the target filing rate, and to compensate for LinkedIn’s high revenue and R&D growth.

LinkedIn also needed to build out its internal patent team. LinkedIn started by leveraging outside firms, but faced the problem of a cold start. A successful patent program needs to be integrated into a company’s culture and business, and it needed to invest. Therefore, LinkedIn added our first full-time patent attorney, Pierre Keeley, in 2012, followed by an experienced patent paralegal, Grace Forker. As soon as additional headcount was approved, we added another key patent attorney Puneet Sarna, from Dolby Labs – and supplemented the team with a secondment of a junior patent attorney. LinkedIn also needed to add to its outside counsel strength, so we brought in an IP strategy firm (Richardson Oliver Law Group) and another patent prosecution firm. Currently, our broad patent team includes our vice president of intellectual property, product and privacy, Sara Harrington; two patent attorneys; one patent paralegal; and a patent litigator. To handle the large influx of invention disclosures, we upgraded our tracking system for invention capture, patent application tracking and tracking metadata associated with our overall portfolio.

Having the executive buy-in and operating capacity to handle the additional inventions did not mean that we would get the additional invention disclosures. As mentioned above, the invention harvesting sessions proved critical to our success. We adopted a white-glove service approach to minimize the impact on inventors. We identified the team members needed for a harvesting session and then lowered the preparation time for inventors to close to zero – the main thing was that they show up to discuss their projects.

Typically, between five and 10 people from a single project would gather and discuss their project for an hour, resulting in in between five and 15 invention disclosures. Projects would typically run for between two and six months before a session was held.

Inventors were a little nervous before the invention harvesting sessions, but ultimately the sessions were seen as successful. The patent team recognized that sessions needed to be positive for inventors – this included clarity about how LinkedIn was going to use its patent portfolio. After one session, a participant commented: “We didn’t know how the meeting was going to go. We thought we were going to get beat down by lawyers. Actually, the session was really positive. The patents are going to allow us to continue to operate the open source project.”

LinkedIn also needed to address a culture in which some inventors viewed patents – and software patents in particular – negatively. Within the company we evangelized about defensive use of patents and the way that our founders had used them to help the broader community. For example, our founders were concerned that a foundational social media patent would fall into the hands of an NPE or someone that might harm emerging social media companies, so they bought it. We also educated inventors on how to apply for patents, what the benefits are and who to contact. We built an internal web page integrating inventor education and inventor recognition, and identified R&D team members who supported the goals, harnessing their advocacy and enthusiasm. We presented to the company in an all-hands meeting, where we gave out lots of T-shirts. We were complementary about an engineering culture which believes in innovation and craftsmanship and wants to market its engineering brand by supporting strategic open source projects, as well as on the professional accomplishment of being recognized for innovation by adding a patent to your profile.

A few simple ideas worked well to keep the patent program in the minds of inventors, such as distributing small branded giveaways across the entire company, focusing on items that inventors would keep on their desks.

Although cash awards for our inventors are an integral part of our incentive program (ours are competitive), we believe that the combination of the white-glove service model and the public recognition has had a higher overall impact on our success.

Looking to the future, our organic filing rate is likely to slow. However, we have been able to catch up on some of our lower filing rates and supplement our portfolio through strategic purchases. In June 2016, Microsoft announced the purchase of LinkedIn, so our plans will adapt to the new overall strategy after the purchase closes.

Increasing its organic patent filings was only one part of LinkedIn’s patent strategy. The second step was to backfill its portfolio through patent acquisition. With a targeted buying program, LinkedIn can grow areas in which it is not developing organic technology and patents. In part 3 of our series, we cover assertion risk mitigation opportunities through patent acquisition and LinkedIn’s acquisition process and results.

>>>> CLICK HERE to CONTINUE READING <<<<

Sara Harrington is vice president of legal intellectual property, product, privacy and Pierre Keeley is director of patents at LinkedIn. Kent Richardson and Erik Oliver are partners of the Richardson Oliver Law Group. Note, in December 2016, LinkedIn was purchased by Microsoft, Inc., and this series represents the pre-purchase patent strategy.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

One comment so far.

American Cowboy

July 13, 2017 01:36 pmSounds like LinkedIn will have a lot of patents that it does not plan to use itself, much like most big corporations and NPE’s.