Buried in the claim language, conditional limitations may be a vulnerability in an otherwise valuable claim. A conditional limitation is a claim feature that depends on a certain condition being present. For example, when or if condition X is present, feature Y is implemented or has effect. Without condition X, feature Y may be dormant or have no effect. Patent owners should be cognizant of possible conditional limitations implications because conditional limitations may affect claim validity and infringement as discussed below in the context of recent U.S. Patent Office and Federal Circuit cases.

Buried in the claim language, conditional limitations may be a vulnerability in an otherwise valuable claim. A conditional limitation is a claim feature that depends on a certain condition being present. For example, when or if condition X is present, feature Y is implemented or has effect. Without condition X, feature Y may be dormant or have no effect. Patent owners should be cognizant of possible conditional limitations implications because conditional limitations may affect claim validity and infringement as discussed below in the context of recent U.S. Patent Office and Federal Circuit cases.

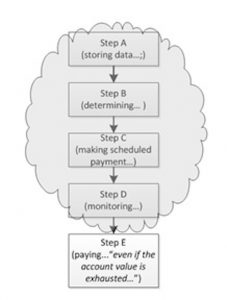

In Ex Parte Schulhauser, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“the Board”) held certain claims as unpatentable based on conditional limitations. Ex Parte Schulhauser, Appeal No. 2013-007847 (PTAB April 28, 2016). The claimed subject matter related to “medical devices for monitoring physiological conditions and, in some embodiments, to a minimally invasive implantable device for monitoring a physiological conditions [sic] and detecting the onset of a critical cardiac event such as a myocardial infarction.” U.S. Patent No. 5987352 (filed July 31, 2008). The Board evaluated the effect of conditional limitations on independent method claim 1 and independent system claim 11. Schulhauser at 1.

Method Claims

Claim 1 at issue in Schulhauser recited a method of:

(A) collecting … [data];

(B) comparing… [data with a criteria];

(G) triggering an alarm state if … [(C) the data is outside the criteria]; and

(D, E, F) [performing a series of steps if the data is inside the criteria]

Id. at 2. (emphasis added).

The Board found that the method contained “several steps [(specifically steps D, E, and F)] only need[ed] to be performed if certain conditions precedents [were] met.” Id. at 6. The Board reasoned that if the determining step (step C) is not reached then the “remaining method steps” (steps D, E, and F) did not have to be performed. Id. at 9. Accordingly, it was not necessary for the patent examiner to show that both paths of a conditional limitation were anticipated or obvious over prior art. Id. The examiner had to show that only one path was anticipated or obvious. Id.

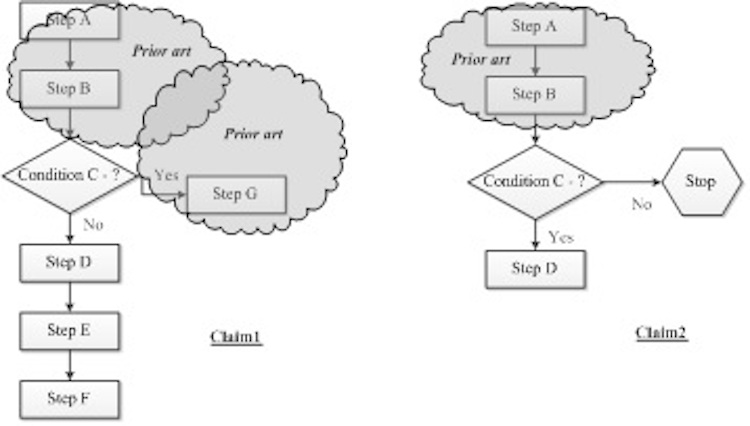

Figure 1. Claim 1 was at issue in Schulhauser. Claim 2 is hypothetical and could also be found unpatentable under Schulhauser. The clouded sections represent steps that were found to be obvious or anticipated under 35 U.S.C § 102 and 103. An examiner can invalidate both examples based on Schulhauser.

Schulhauser suggests that certain conditional limitations in method claims can be given patentable weight because a method claim requires that specific steps are performed with respect at least one condition. See id. However, alternate steps based on the condition may be given no patentable weight because an alternate step may not need be met or performed. Id. If a method claim is drafted with alternative conditional limitations, every alternative path should be novel and not obvious to help ensure the method claim is valid. See id.

From an infringement perspective for method claims, the Federal Circuit has made it clear that if all claimed steps are performed or attributable to an alleged infringer, then there can be liability for infringement. Akamai Techs., Inc. v. Limelight Networks, Inc., 797 F.3d 1020, 1025 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (holding that the defendants infringed even though two of the claimed method steps were performed by customers and not directly performed by the defendants). Yet, there is little case law discussing how conditional limitations effect infringement. For example, infringement of conditional limitations was raised in Lincoln, but the court did not reach a holding on this issue. Lincoln Nat’l Life Ins. Co. v. Transamerica Life Ins. Co., 609 F.3d 1364, 1369 (Fed. Cir. 2010). In Lincoln, the plaintiff argued that the defendant infringed a claimed method by performing four out of five steps. Id. The plaintiff argued that the fifth step did not need to be performed because it was conditional. Id. The court rejected this argument and held that there was no infringement because the fifth step was not conditional. Id.

In arguing infringement, the plaintiff cited Cybersettle, an unpublished Federal Circuit case, stating that “[i]f the condition for performing a contingent step is not satisfied, the performance recited by the step need not be carried out in order for the claimed method to be performed.” Brief for Appellant at 6, Lincoln, 609 F.3d 1364 (Fed. Cir. 2010) (No. 09-1403, -1491) (citing Cybersettle, Inc. v. National Arbitration Forum, Inc., 243 Fed. Appx. 603, 2007 WL 2112784, at *4 (Fed. Cir. July 24, 2007)). However, not only is Cybersettle unpublished, this quoted language in Cybersettle is dictum. See Cybersettle, 243 Fed. Appx. 603, 2007 WL 2112784, at *4. It is not certain how the Federal Circuit would decide an infringement case of this nature in the future, but it is likely that plaintiffs will continue to rely on Cybersettle to support infringement claims against defendants who do not perform conditional steps of a method.

System Claims

Independent system claim 11 at issue in Schulhauser was directed to a cardiac condition monitoring system that recited “various ‘means for’ limitations involving functions substantially similar to those recited in [method] claim 1.” Schulhauser at 13. The Board reasoned that the system recited a structure capable of performing the claimed function in its entirety regardless of whether the condition was met in specific instances. Id. at 14. Therefore, the Board gave patentable weight to the means-plus-function conditional limitation where the specification provided sufficient structure of a processor that executed instructions for performing the claimed functions. Id. at 14-15. The Board held that in order to find anticipation or obviousness, the examiner must identify prior art that is capable of performing all of the recited functions. Id.

Post Schulhauser, the Board has found patentable other means-plus-function claims that recite a structure configured to perform conditional limitations, which must be present regardless of whether the condition actually occurs. See Ex Parte Morichika, Appeal No. 2014-000220 (PTAB April 5, 2017). Additionally, system claims including conditional limitations not written in means-plus-function format have been found patentable, citing to Schulhauser. See Ex Parte Conti, Appeal No. 2016-001320 (PTAB February 10, 2017); Ex Parte Lidstrom, Appeal No. 2016-003867 (PTAB December 30, 2016); Ex Parte Bortoloso, Appeal No. 2015-006985 (PTAB October 24, 2015). The patents involved in these cases include system claims that claim structure such as a processor or memory that is capable of or configured to perform a conditional feature. Id.

The question is whether system conditional limitations outside this context would be given patentable weight. For example, Judge O’Malley concurring in part in MPHJ highlights that certain system conditional limitations may be given no patentable weight. MPHJ Tech. Invs., LLC v. Ricoh Ams. Corp., 847 F.3d 1363, 1379 (Fed. Cir. 2017). In MPHJ, the claim at issue was a system claim for transmitting electronic information to external destinations. Id. at 1365. Judge O’Malley opined that a “wherein” clause invoking certain protocols “when” a certain application was used is a “conditional, non-limiting, nonspecific clause that [did] not narrow the claim.” Id. at 1379. Judge O’Malley cited to Federal Circuit authority stating that “optional elements do not narrow the claim because they can always be omitted.” Id. (citing In re Johnston, 435 F.3d 1381, 1384 (Fed. Cir. 2006)). A portion with the conditional limitation of the system claim at issue in MPHJ is reproduced below:

at least one processor responsively connectable to said at least one memory, and implementing the plurality of interface protocols as a software application for interfacing and communicating with the plurality of external destinations including the one or more of the external devices and applications,

wherein one of said plurality of interface protocols is employed when one of said external destinations is email application software …

Id. at 1366.

Accordingly, conditional limitations that are not recited as structure that is capable of or configured to perform the conditional function may render the conditional limitation as “optional” and not truly “conditional.” The M.P.E.P. provides, “Claim scope is not limited by claim language that suggests or makes optional but does not require steps to be performed, or by claim language that does not limit a claim to a particular structure.” See M.P.E.P § 2111.04; see also M.P.E.P §§ 2103(C) and 2173.05(h). Furthermore, all alternative conditional limitations in system claims that are not limited to a particular structure (e.g., a processor configured execute instructions including the alternatives) may also be given no patentable weight if every alternate limitation is interpreted as “optional.” See MPHJ, 847 F.3d at 1379. MPHJ is an example of possible negative validity implications that may arise from conditional limitations in system claims. It is unclear however if infringement involving conditional limitations in system claims would follow Cybersettle reasoning of not requiring an accused product to have a conditional feature to find infringement.

The Federal Circuit will likely see these issues in the future and possibly review the reasoning in Cybersettle and Judge O’Malley’s MPHJ concurrence. Until then, claim drafters should carefully craft system claims to avoid limitations that may be construed as “optional.” Terms such as “optionally,” “if,” or “may” should be evaluated and likely removed from any claims. Further, temporal language in system claims such as “when,” “while,” “upon,” “before,” “after,” etc. can often be redrafted by including structure that is capable of or configured to perform the function and removing the conditional phrasing (e.g., temporal language) altogether.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

24 comments so far.

patent leather

August 30, 2017 10:11 pm@21 NWPI, “Couldn’t you just rewrite your claim language to recite a single step of “performing nonobvious process, only upon the condition tales”?”

I included the “doing nothing” step for illustrative purposes. My claim in #5 (“1. A method comprising: flipping a coin; when the coin is heads then a) standing and doing nothing; when the coin is tails then b) performing [nonobvious process].”) is really the same as: 1. A method comprising: flipping a coin; when the coin is tails then performing [nonobvious process].

I was illustrating why that claim isn’t patentable. Because if the flip was heads, no action is taken, thus if someone flips a coin to heads then they would infringe this claim. If this claim was really patentable, then doing a prior art activity would infringe which of course isn’t allowed.

If anyone thinks this claim is really patentable, then you are basically saying that the court should break each prong into what is old and what is new and not count what is old with regard to a 102 analysis. While there is one old case that took this approach (the name escapes me), this approach is not current law (and probably should not be).

JTS

August 30, 2017 08:31 pm1. A method comprising:

receiving event X;

determining whether event X satisfies condition Y;

providing a first operation configured to be performed based on a determination that X satisfies Y;

providing a second operation configured to be performed based on a determination that X does not satisfy Y.

There are many ways around the very real problem raised by the article above. Key: a positive step of evaluating the condition, and then the existence of elements that available to be invoked based on the evaluation.

Anon2

August 30, 2017 04:57 pmNwtpti@21

I agree with you there… I did not write the claim. A mere aggregation of something useless or known with something patentable, i.e. a collection which is not an inventive combination of the something useless or known with the something otherwise patentable by itself, is not a collection which should be claimed as the invention. One clearly should not bother with the limitations to the something useless or known and having no inventive combinatory contribution.

My point(s) are with respect to the manner by which something which behaves conditionally or a method which is to be carried out conditionally, can be claimed… assuming that the claim as a whole is an inventive combination.

Name withheld to protect the innocent

August 30, 2017 02:43 pmI think it is clear that it is a method capable of responding to a series of coin tosses, not just a single (for all eternity) coin toss, and it responds to each coin toss differently

That’s fine if you have a series of coin tosses. However, what if your competitor’s system is only set up to toss tails?

Let me ask you this. What is the purpose of the following claim language? “doing nothing under the condition heads.” Why would you include that in the claim language?

Couldn’t you just rewrite your claim language to recite a single step of “performing nonobvious process, only upon the condition tales”?

patent leather

August 30, 2017 11:18 am@17 Peter Kramer, thanks, I think that might work (of course there is a lack of CAFC case law here). I would delete the comma in the second prong so it reads, “performing nonobvious process[,] under the condition tales.” You don’t want each step to be constructed as a condition and then action, but rather each step is always positively performed regardless of what condition occurs. I think your claim would come down to what is in the spec, e.g., if there is a flowchart showing they are conditional blocks then the claim might fail but if the flowchart shows sequential operations with no conditions then it could very well pass muster.

Anon2

August 30, 2017 09:05 amNwtpti@18

I see you aren’t reading into the claim this time… I think it is clear that it is a method capable of responding to a series of coin tosses, not just a single (for all eternity) coin toss, and it responds to each coin toss differently.

Assuming the infringer actually performed the method, all you need is evidence which includes more than one toss… video evidence, testimony, or in the case of a system performing the method, having the system respond to both conditions as they randomly appear in a series of coin tosses.

Name withheld to protect the innocent

August 30, 2017 07:48 am@17

How does one infringe that claim if ALL of the limitations need to be met?

Peter Kramer

August 30, 2017 07:26 am@patent leather

How about:

A method capable of responding to two mutually exclusive conditions, said conditions resulting from a coin toss, said method comprising,

doing nothing under the condition heads, and

performing nonobvious process, under the condition tales.

Name withheld to protect the innocent

August 29, 2017 01:04 pmI would choose something which …

So would I. However, sometimes you get stuck defending language you didn’t write, and I try to avoid amending claims unless it is for purposes of getting around the prior art.

Anon2

August 29, 2017 12:03 pmNwtpti @14

I’m not so sure I whether should feel more secure or simply perplexed in knowing that I have been unsuccessful in a purposeful attempt to write a screwy invalid claim…

Notwithstanding my tending to agree with what you point out… words still matter… and I would choose something which specifically claims both X and Y are performed, with the specific limitations of A and B being the conditions upon which performance of X or respectively Y are “based on” or “responsive to”.

Name withheld to protect the innocent

August 29, 2017 11:43 amI would argue that method 1 is actually indefinite because it purports to conditionally define something

Indefinite? “if its claims, read in light of the specification, delineating the patent, and the prosecution history, fail to inform, with reasonable certainty, those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention” is the standard for indefiniteness per Nautilus. I don’t think one skilled in the art would have a problem understanding that language. It’s not the language I would use but, but that doesn’t mean it is indefinite.

I just ond’t think method 1 is amenable to being given any patentable weight because of what it explicitly tries to do.

If you are one of certain members of the Board (BTW — plenty of APJs given those kind of limitations patentable weight), then perhaps the claim language is not given weight. However, I don’t think the broadest reasonable interpretation of language is REASONABLE when limitations are read out of the claim so as to make it indefinite.

Anon2

August 29, 2017 11:21 amNwtpti @11

I too like phrases such as “based upon” or “responsive to”. these further identify that that which is conditional is the behavior of the actual entity claimed.

Anon2

August 29, 2017 11:16 amNwtpti @11

Your reply seems to indicate that you allege that method 1 and 2 as explicitly claimed mean the same thing. Is this true? I would argue that method 1 is actually indefinite because it purports to conditionally define something, as opposed to method 2 which simply defines something which does things conditionally.

I understand that you have prefaced your statement with “assuming all of the limitations are given patentable weight”, I just ond’t think method 1 is amenable to being given any patentable weight because of what it explicitly tries to do.

Name withheld to protect the innocent

August 29, 2017 10:51 amAnon2 @9

Assuming all of the limitations are given patentable weight, then 3 is nearly the same as 1 and 2. However, the terms “if” and “when” can be construed to have different meaning. Although both could be considered as creating conditional statements, the term “when” could also be construed to require a timing relationship (comparable to “while”).

Consider the differences between the following terms:

A “if” B

A “when” B

A “while” B

A “based upon” B

A “responsive to” B

Depending upon the circumstances, I prefer to use “based upon” or “responsive to” over terms such as “if” or “when”

CP in DC

August 29, 2017 09:50 am@6 Patent Leather

Simplicity in the claim is more problematic. Generally, in medical diagnostics or biotech the method to determine the disease is newly discovered. The treatment is generally known, but accuracy in diagnosis is critical.

The examiners and PTAB generally find that any discovery to predict the disease is directed to a law of nature or natural phenomena. Most of us do not agree that finding causation or being able to accurately predict such causation is merely the discovery of a law of nature. Once the inventive aspect is discarded as directed to a “law of nature” the examiners reject the remainder as well understood and routine in the art. So to avoid ineligibility, conditional limitations are placed into the claim to write in the diagnostic test.

Here is the rationale by the PTAB.

[A]s to part one of the Supreme Court’s test, Appellants’ claim 1 is expressly directed to the law of nature discovered by Appellants—that the presence of the TT genotype at SNP rs2297480 is indicative that an individual having a bone disorder will respond to treatment with bisphosphonates.

As to part two of the Supreme Court’s test, the only other step in Appellants’ claim 1, administering bisphosphonate to the individual having the bone disorder, is a well understood and routine treatment step for such patients, as explained in Appellants’ Specification. See Spec. 1 (“Oral bisphosphonates are the commonest first-choice treatment where a reduction in osteoclasis would be beneficial, for example, for post-menopausal osteoporosis …..”).

It’s difficult to see so many rejections on patent eligibility in a field directed to treating diseases that occur in nature. Who wants to cure artificially created diseases?

Anon2

August 29, 2017 08:18 amJust a follow-up to post @8

Consider the following pseudo (and decidedly non-standard) claims:

Method 1) A method such that:

IF A, the method COMPRISES doing X, and

IF B, the method COMPRISES doing Y.

Method 2) A method comprising:

DOING X; AND

DOING Y,

wherein X is done when A, and Y is done when B.

Does the meaning of the following claim fall closer to method 1 or method 2?

Method 3) A method comprising:

performing X when A; AND

performing Y when B.

Anon2

August 29, 2017 07:06 amIf a system is configured to perform according to various criteria, a few specific different things, infringement can be shown quite easily by having the system operate, and perform the few specific different things in response to the various criteria.

Patent Leather, A system which flips a coin and does nothing when the coin is heads and does something novel when the coin is tails, can be tested for both behaviors, as relevant conditions apply. A system which does only one thing is not a system arranged to do both.

The apparent subtlety is the difference between claiming in the alternative, different things each of which does different things, or claiming a single thing which does different things in response to different conditions.

One must be careful choosing language which distinguishes between on the one hand claiming in the alternative something which does X if A OR does Y if B (where for whatever reason the OR indicates conceptual exclusivity) versus some single thing which is arranged so as to do X when A and ALSO to do Y when B.

In this second case only a single something which is arranged, ready, capable etc. to do both X and Y at different times in response to different conditions will infringe.

According to logic, language, limitations… there is no ambiguity in a carefully written claim to a system.

Would this change just because one is dealing with a “method”? There does not seem to be any reason why not. A method claim which has a step X which is performed IF A obtains, requires performance for infringement. If, for whatever reason, in the context of the defendant’s conduct, A simply never performed X, it has not been shown that A performed the relevant step of the method. Infringement is not some college philosophy hypothetical, if the evidence does not show X was performed, and also it was performed in the company of A obtaining, a limitation simply was not met.

Name withheld to protect the innocent

August 29, 2017 01:05 amYet it is accepted that a conditional claim can be infringed so long as only one prong is performed.

I haven’t seen that case law. Infringement requires all limitations be practiced. If you have mutually exclusive limitations, then how can all be practiced?

Typically, when you have conditional limitations, it is just one branch of the logic tree is patentable.

For example, a method that involves: doing nothing if nothing bad happens versus doing [special fix-it step] when something bad happens.

In these instances, you don’t recite both branches of the logic tree. You only recite the branch that is patentable.

The easy way to get around the Board’s broadest unreasonable interpretation is just to claim that the condition has happened. For example:

A method of fixing a computer, comprising:

identifying that a particular problem with the computer has occurred;

responsive to the particular problem being identified, perform special operation to fix computer.

The Board’s analysis is premised on the possibility that the condition hasn’t been met, and therefore, the step need not be performed. However, if you positively recite that the condition has been met, you’ve gutted the Board’s analysis.

patent leather

August 28, 2017 09:33 pm@CP in DC, that claim could have been saved by removing the condition. Something like this: “… determining that the TT genotype is present in the sample; and administering intravenous [pamidronate] to the individual.”

patent leather

August 28, 2017 08:46 pmThere is nothing in this case that is contrary to law or troublesome. Conditional claiming is one of the trickiest things to get right when prosecuting, yet mastering it is extremely important when prosecuting software and electronics in which conditional claiming is sometimes unavoidable. Consider the following claim:

1. A method comprising: flipping a coin; when the coin is heads then a) standing and doing nothing; when the coin is tails then b) performing [nonobvious process].

If only one prong is needed to be patentable during examination, then this claim would be patentable by virtue of the second prong. Yet it is accepted that a conditional claim can be infringed so long as only one prong is performed. In fact, it would be impossible to perform both prongs of this claim. So a rule that both prongs of a conditional claim have to be performed to infringe would render most such claims (unless drafted very cleverly) uninfringeable.

So looking at the example claim above, if this claim were really patentable, then one only need to flip a coin (to heads) and stand and they would infringe this claim!

If the prosecutor intends to have both prongs positively recited, then he or she should try something like this:

2. A method comprising: flipping a coin; providing an operation defined by when the coin is heads then a) standing and doing nothing, and when the coin is tails then b) performing [nonobvious process]; and performing the operation.

I’ve been on both sides of conditional claims and I’ve seen many of the most prestigious patent firms botch conditional claims to the point where they are unpatentable or uninfringeable. Practitioners should be very cognizant of these issues and when drafting conditional claims should be VERY careful in how they are worded and how the logic flows.

CP in DC

August 28, 2017 08:04 pmCondition limitations help claims pass the eligibility test in personalized medicine or diagnostic claims. Otherwise, the claims are considered either an observation of natural phenomena or a mental process (determine and diagnose). However, these condition limitations don’t save every claim as in Ex Parte Chamberlain. Here is the claim that the PTAB found ineligible, even though it closely followed the “patent-eligible” julitis example by the PTO guidelines.

A method of treating osteoporosis in a human individual having a BMD T score of -1 or less, the method comprising:

determining in a nucleic acid sample obtained from the individual, the presence of a TT genotype at single nucleotide polymorphism rs2297480 (SNP rs2297480) in the farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FDPS) gene,

wherein the presence of the TT genotype is determined by hybridizing the nucleic acid sample to a nucleic acid probe which comprises SEQ ID NO: 1 or the complement thereof; wherein the probe or the nucleic acid sample is immobilized in a nucleic acid array, and;

administering intravenous [pamidronate] to the individual if the TT genotype is present in the sample.

Even though the condition would be met “wherein….” and an action was required “administering…” the claims did not survive.

Without the condition limitation, the claims don’t stand a chance.

Name withheld to protect the innocent

August 28, 2017 07:15 pmI believe that somebody will have to appeal the PTAB to have this decision overturned.

Someone did in Ex parte Fleming, but I just looked it up and the appeal was dismissed about 4 months later (this happened 5 months ago). I’m not really sure why it happened.

I wasn’t aware of the Hehenberger case. However, the logic contained therein is rarely applicable — there are very few single step method claims.

I agree about your point as to the difference between method and device claims. A machine configured to do [conditional operation] must have such a configuration whether or not the operation is ever performed. As such, it seems incongruous to have the same limitations acceptable for a machine but not for a method.

BTW — you wouldn’t want to perform ABC together as a method claim (separately claim AB and AC is fine) because someone couldn’t infringe that claim. If you meet condition B, then condition C cannot be met and vice versa.

sgb

August 28, 2017 04:43 pmI agree with name withheld, but I think that the public policy argument will win the day in this one because the decision was based on the “broadest reasonable interpretation.” However, the broadest reasonable interpretation is premised on what a skilled artisan would understand the claim to mean and, moreover, a skilled artisan understands conditional logic.

Second, this only applies to method claim, which serves no public policy purpose (which the entire reason of the BRI). Assume you have a process that (A) determines the temperature; (B) performs X if the temperature is greater than 100 degrees; and (C) performs Y if the temperature is less than 100 degrees. Assuming that each step above (i.e., A, B, and C) is novel, based on Schulhauser, you can claim AB and AC separately, but you cannot claims ABC together in a method claim. But a system claim (that performs the method) can claim ABC. It doesn’t make any sense why method claims can have no conditional logic, but apparatus or system claims can have unlimited logic.

Schulhauser is a great example of the USPTO gone wild with the BRI. Unfortunately, I believe that somebody will have to appeal the PTAB to have this decision overturned.

Also, name withheld, under your scenario, ex parte Hehenberger is structurally identical to your hypothetical. The majority opinion ignores Schulhauser, but the concurring opinion states that, if they ignored the condition, there would be no claim. So therefore, they can to interpret the entire claim.

Name withheld to protect the innocent

August 28, 2017 11:33 amLet’s make a couple things clear.

If someone wanted to make the argument, Ex parte SCHULHAUSER might fall under the guise of illegal substantive rule making by the USPTO. The use of precedential opinions to make pronouncements on substantive law is arguably not permitted by law.

Second, the line of Board cases relied upon the USPTO are very weak. The original case (ex parte Katz) doesn’t even cite Federal Circuit case law for their argument that conditional limitations can be ignored. The case law I’ve seen cited refers to “optional” limitations, but a conditional limitation is not the same as an optional limitation.

A synonym for “limitation” is a “condition.” If you think about it, all limitations are conditions.

What is the difference between:

A method of creating a prince, comprising:

going to a swamp with a princess; and

“kissing a green frog by the princess” or “if a frog is green, kissing the frog by the princess.”

Would the PTAB argue that a princess merely appearing at a swamp is anticipatory prior art using the second quoted language because not all frogs are green and therefor that step isn’t necessarily performed? What the USPTO fails to recognize is that ALL limitations must be considered, and the claimed invention, AS A WHOLE, must be anticipated or rendered obvious by the applied prior art.

The Board’s actions are just another in a line of tricks the Board uses in order to affirm rejections that they would otherwise have to reverse an Examiner on.