As previously reported, the past year of ex parte appeals data from the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), shows the USPTO’s Examining corps generating a consistently high reversal rate. This high reversal rate is likely the result of a confluence of many different factors and the goal of this post is not to propose solutions. However, these reversals are costing applicants big money. This is regardless of whether the reversal rates reflect the overall quality of the examination process (each reversal is a “defect”) or whether each reversal is a statistically random data point from PTAB judge panels non-uniformly applying the patent laws. This article shows the monetary effects of these high reversal rates.

As previously reported, the past year of ex parte appeals data from the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), shows the USPTO’s Examining corps generating a consistently high reversal rate. This high reversal rate is likely the result of a confluence of many different factors and the goal of this post is not to propose solutions. However, these reversals are costing applicants big money. This is regardless of whether the reversal rates reflect the overall quality of the examination process (each reversal is a “defect”) or whether each reversal is a statistically random data point from PTAB judge panels non-uniformly applying the patent laws. This article shows the monetary effects of these high reversal rates.

With overall ex parte appeal pendency at 18.4 months (from the PTAB’s Aug, 3 2017 presentation to the PPAC) applicants filing a notice of appeal today can expect to spend about two years from start to finish on the process. Most of that time is spent waiting. While patent term adjustment can compensate on the backend, for many applicants (particularly startups and small companies), the sooner the patent protection the better. For one, investors are often more likely to invest when business has a definitive right of protection. For another, with patent protection the business can stop infringing use and sue for damages sooner. This, and the costs of filing an appeal typically disincentivize patent applicants from taking the PTAB ex parte appeal route.

While societal and macroeconomic cost of PTAB appeals is for the economists, there is an estimable direct cost to patent applicants for every appeal filed—what they pay their lawyer to draft the appeal documents. Earlier this month, AIPLA released its 2017 Report of the Economic Survey, in which respondents were asked to provide their fee for preparing an appeal. The questionnaire asked for input from those who had actually filed an appeal in the last 12 months. According to the Report the median fee to prepare an appeal without oral argument (which represents the vast majority of ex parte appeals) has remained quite consistent across the 14 year window from 2004 through 2016. See p. 30. In 2004, the median fee was $3,600 while in 2016, the cost had risen to $4,200. While this is a median fee, meaning 50% of appellants paid more, and 50% paid less, it represents probably the best objective measure of the average cost of an appeal to any particular patent applicant we have access to.

In attempting to estimate total cost of the process, it is important to be aware of some data caveats. More appeals get filed than are docketed at the board since prosecution can be reopened or RCEs can be filed after the Examiner’s answer to take newly allowed subject matter. Furthermore, since on p. 34 of the 2017 Report of the Economic Survey the graph shows the current mean cost for an appeal being something slightly north of $5000, both of these pieces of information suggest that any estimates in this article using median values very likely underestimate the total dollars spent by applicants on their lawyers involved in ex parte PTAB appeals. The data in this post therefore represents a very conservative estimate. Also excluded are the government fees from this data set, which are a significant cost, as the appeal forwarding fee for each appeal ranges from $500 for micro entities to $2000 for large entities.

An ex parte appeal may involve just one issue of law or multiple issues of law. However, for the patent applicant to get a patent, the applicant must prevail on ALL the issues of law on appeal for at least one claim on appeal. Currently, the USPTO’s published appeal statistics do not reflect what happens to each legal issue on appeal in each case—the USPTO’s statistics are based ONLY on the overall outcome of the appeal. A reversed decision from the USPTO means the applicant won on all issues in appeal; an affirmed-in-part decision means the applicant lost at least one issue for at least one claim (there is no telling which from raw USPTO data), and an affirmed decision means the Board agreed with the Examiner for ALL the issues on appeal.

When an appeal is brought to the Board, the appellant/applicant is asking the Board rule that the Examiner’s position on a particular issue is erroneous. There are many affirmed-in-part appeals that issue from the Board where the only issue affirmed is obviousness type double patenting which the appellant did not challenge (think terminal disclaimer), but where the Examiner was reversed on the actually substantively argued issues (35 USC 102, 103, 112, 101, etc.). Because of the existence of these kinds of cases, an appellant is benefited when the Board reverses the Examiner for any substantive issue, as it finally (in many cases) resolves that particular issue between the Examiner and the applicant.

For this reason, for the purposes of this analysis, the assumption is made that a reversal by the Board on any individual issue is a benefit to the applicant worth paying the entire attorney cost of the Appeal to get. This oversimplifies the situation to an extent, but is a fair approximation, given that the applicants were willing to pay for a resolution of most of the issues by the Board in an appeal in the first place.

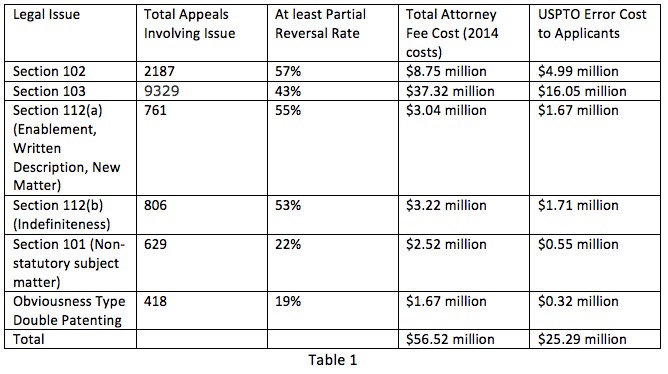

Table 1 shows data using a median attorney fee appeals cost of $4000 per appeal. Since the appeals being decided today were filed about two years ago, and the median cost of an appeal was $4000 in 2014, the total cost to Applicants of appeals decided today would be best measured in 2014 dollars.

Since a fair number of appeals involve more than one issue, the total cost number in the table only represents the total error cost to Applicants to overturn erroneous rejections made by the Examiners across all the issues. To attempt to estimate the approximate total error cost, 372 of the 11458 ex parte appeals decisions from 8/23/2016 to 8/23/2017 were randomly reviewed to determine which were single issue vs multi-issue decisions. This sample size was designed to provide a 5% margin of error at a 95% confidence level. The observed percentage of multi-issue cases was 40.59%, which, taking into account the margin of error, means that between 35%-45% of ex parte appeals considered in this dataset involved more than one issue. Reducing the total costs in Table 1 by this percentage to weed out double counting of costs means that applicants spent between $31.09 and $36.74 million in total on attorney fees for appeals and that the resulting attorney fee cost of USPTO reversal error during the year was between $13.91 million to $16.44 million.

These are not minor sums of money, particularly since all of this money was spent by applicants in just one year. Patent attorneys do not have fee schedules like the USPTO where they charge micro, small, and large entities different fees based on how much the inventors earn. Because of this, the cost of appeals as a percentage of gross income accordingly falls disproportionately on independent inventors and startups when compared with large entities.

Some would argue that Applicants only appeal cases that they think they can win. However, what is quite clear from this data is that the Examiners (and the supervisors who participate in the appeal conferences) are not as good as might be anticipated at picking winning cases for the USPTO—and applicants are paying tens of millions of dollars per year as a result.

As the old saying goes, “Ignorance of the law is no excuse.” So there seems to be no good reason that the Examining corps’ inability to apply the law to the facts in ex parte appeals should be costing applicants this much money yearly. We should not have 2X higher reversal rates for novelty and obviousness than statutory subject matter. However, until something changes about how the USPTO decides to take cases to the board, it is apparent that patent applicants will continue to have to be patient and pay.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

8 comments so far.

Louis J. Hoffman

September 13, 2017 01:44 pmThis excellent article grossly underestimates the cost of erroneous rejections.

(1) Many applicant abandon applications after faulty rejections because they cannot afford appeal costs.

(2) The $4000 cost referenced to do an appeal refers only to the brief (which sounds low to me anyway), and it doesn’t include reply brief, oral argument, and PTO fees (notice of appeal and appeal-submission fee plus any extensions).

(3) In at least some instances, the patent-term adjustments referenced for successful appeals do not benefit applicant, such as when there is a terminal disclaimer; in those cases, the time wasted on appeal costs applicant patent term, and wrongly so.

AnExaminer

September 8, 2017 04:18 pmUnder Lee:

Your experience under Lee appears to have been vastly different than mine. I haven’t notice any substantive differences between Kappos’ time and Lee’s that can be attributed to Lee, especially when it comes to how I examine my cases. The same cannot be said for the changes made between Dudas and Kappos. Lee’s tenure just felt like more of the same.

As for your comment about “Examiners were told that every Action that was essentially re-work (e.g., second non-final, re-open after AFCP, Allowance after appeal brief, etc.) would be reviewed for quality.” That’s the first time I’ve heard of anything like that, but since I do almost no re-work it doesn’t bother me. Also, second non-finals and re-opening after filing of an appeal brief are indicative of examiner errors in the prior office actions, so it seems logical for those cases to receive more scrutiny.

Just my opinion, but this is how I see things:

Dudas screwed everyone with the second pair of eyes, and “reject, reject, reject” mentality.

Kappos reversed the anti-patent policies of Dudas but screwed examiners, and ultimately the public, by lowering the net number of hours spent reviewing applications via a variety of changes (new count system that resulted in the more difficult arts receiving less net counts for the same amount of work, AFCP that took counts away from examiners that they use to receive, First Action Interview pilot that results in examiners doing what is essentially three office actions rather than two in the first round of prosecution, etc.).

Lee…I can’t think of a single thing that is attributable to Lee that changed my day-to-day job. Under Lee, SPEs have been required to review more cases each quarter from primary examiners than they use to, but that hasn’t changed how I do my job.

AnExaminer

September 8, 2017 03:30 pm“what is quite clear from this data is that the Examiners (and the supervisors who participate in the appeal conferences) are not as good as might be anticipated at picking winning cases for the USPTO”

That is a curious way to look at it. Did you consider the other side of the coin that attorneys are not as good as might be anticipated at picking winning cases?

Examiners do not pick the cases that are appealed, Applicants and their attorneys do. Even though examiners can reopen at the appeal conference, the appeal stats should still show a large selection bias in favor of applicants for cases that are appealed. However, that’s not what we actually find. In FY16 examiners were completely affirmed 57.4% of the time, and affirmed in part another 12.9% of the time. These stats vary a little year to year, but not by much over the last few years. So where is the article railing against how much patent attorneys are costing their clients on erroneous appeals? After all, the article says that the total attorney fees are $56.56 million, so with 57.4% of appeals being completely affirmed and completely ignoring the affirmed-in-part cases, wouldn’t that mean that attorney “errors” are costing their clients at least $32.47 million? Far more than the alleged examiner “error costs” of $16.44 million. As the old saying goes, “Ignorance of the law is no excuse.” So there seems to be no good reason that the patent attorneys’ inability to apply the law to the facts in ex parte appeals should be costing applicants this much money yearly.

Under Lee

September 7, 2017 12:32 pmGene:

Many things started at the workgroup level very shortly after Lee announced her quality initiative.

Increased training, reviewing re-work, community outreach, goals/numbers art units were expected to reach, etc.

The problem was all of these things lacked substance or had unintended consequences.

One hour module training directed to an audience of teenagers, artificial numbers/goals that discouraged remedial training, coaching errors and actual errors unevenly applied, community partnership meetings that felt so scripted, no actual dialogue took place, information from the TC director level not being practiced at the art unit level, review processes that encouraged maintaining subpar work.

It felt like, and still feels like, chaos.

It felt like Lee told everyone to increase quality, and everyone started implementing all these ideas without any actual foresight.

Some things occurred that would be met with outrage from the public. Senior Examiners quietly expressed their concern between each other, but no Examiner will ever discuss them in the open for fear of losing their job. But if you listen closely, you may be able to the hear the whispers.

It may not be fair to blame Lee for all of these issues. However, she was the Director when all these things were implemented/occurred. And all of these things were implemted/occurred when she announced her quality initiative.

I don’t think there will ever be any paper trail or link about these issues.

Gene Quinn

September 7, 2017 11:02 amUnder Lee & Kappos versus Lee-

Can you elaborate on Lee’s initiatives that negatively influenced examiners? Is there any paper trail or link available?

-Gene

Kappos versus Lee

September 7, 2017 10:33 amIt would be interesting to see the trends for the last 10 years and the following 2 years.

Under Kappos the pressure seemed to be directed toward doing anything and everything you could to allow an application.

Under Lee the pressure seemed directed toward issuing that next rejection.

There is so much discussion about Lee and the PTAB. What is lost in these discussions is the damage done by Lee to the Examining corps.

So many of the things implemented under her were a complete disaster. Her initiatives were implemented with surface dressing and no substance.

Almost everyone in the corps is happy to see her gone.

Under Lee

September 7, 2017 10:30 amInteresting article. I understand the the numbers point to Examiners not knowing how to apply the law. However, I think there is a little more to the story.

I remember not too long ago some Examiners were told that every Action that was essentially re-work (e.g., second non-final, re-open after AFCP, Allowance after appeal brief, etc.) would be reviewed for quality.

Not sure if this was TC or agency wide, but it felt that way.

The premise made sense. The PTO wanted to ensure quality and fairness to Applicants.

However, what really happened was Examiners felt pressured to maintain their rejection. No one wanted their previous Action to be used in support of an error in a current Action. The pressure was directed toward taking it to the board – better to be overturned in 2 years than get an error today.

The problem is the review process. If an Examiner is issued an error, even if it was not an error, there is almost no chance of getting it removed.

This appeared to be another initiative by Lee which did not consider the unintended consequences.

Wei Wei Jeang

September 6, 2017 07:21 pmI cannot agree with you more. It’s been infuriating having to appeal my clients’ cases and I have near perfect reversal rate on my appeals.