Owens Corning v. Fast Felt (Fed. Cir. 2017) illustrates an example of how the broadest reasonable interpretation (BRI) standard increases the chances that an obviousness argument could:

- successfully invalidate a patent claim during a post grant patent review proceeding; and

- make it more difficult to overcome an obviousness rejection during patent prosecution.

Background of Owens Corning Case

In Owens Corning, the petitioner was successful in invalidating a patent claim during an Inter Partes Review (IPR) before the Patent Trademark and Appeal Board (“Board”). Fast Felt (patent owner) owned U.S. Pat. No. 8,137,757 which described and claimed methods for printing nail tabs or reinforcement strips with a lamination roll on roofing or building cover material. The specification explained that the nail tabs reinforced specific locations on roofing or building cover material where nails would be driven through to attach it to a wood roof deck or a building wall stud wall.

Claim 1 of the ‘757 Patent recited:

- A method of making a roofing or building cover material, which comprises treating an extended length of substrate, comprising the steps of:

depositing tab material onto the surface of said roofing or building cover material at a plurality of nail tabs from a lamination roll, said tab material bonding to the surface of said roofing or building cover material by pressure between said roll and said surface. (emphasis added).

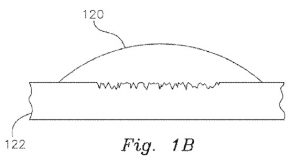

To add context to the claim, refer to the figure below. Reference number 120 identifies the tab material that forms the nail tabs, and reference number 122 identifies the roofing material. You can also view the patent itself by clicking on the patent number above.

Claim 1 states that the tab material is applied to a roofing or building cover material via a lamination roll. Of significant importance is that the claim was broad enough to cover nail tabs applied via the lamination roll to roofing and “building cover materials,” as discussed below.

Owens Corning attacked the validity of the ‘757 Patent by saying it was an obvious variation of U.S. Pat. No. 6,451,409 (Lassiter). Lasiter taught a process using nozzles to deposit polymer nail tabs on roofing and building materials. But instead of using nozzles as in Lassiter, the nail tabs as recited in Claim 1 of the ‘757 Patent were applied with a lamination roll. Owens Corning also referenced several secondary references disclosing the use of a lamination roll or printing process and argued it was obvious to use the lamination rolls or printing processes instead of the nozzles and thus arrive at the claimed method steps. The secondary references were U.S. Pat. No. 5,101,759 (Hefele) and U.S. Pat. No. 6,875,710 (Eaton).

Obviousness Issue

The primary legal issue was whether it would be obvious to replace the nozzle disclosed in the Lasiter reference with the lamination roll / printing process taught in the secondary references to arrive at the claimed invention.

I. BOARD’S OBVIOUSNESS ANALYSIS

In Patent Office examinations, patent claims are given their broadest reasonable interpretation (BRI). Referring to Claim 1 of the ‘757 Patent, the claim was broad enough to cover both roofing cover material and also building cover materials. The Board in deciding the issue of obviousness had limited the meaning of “roofing or building cover material” to only include cover material using asphalt. In other words, the Board focused on the roofing cover material.

This narrowed claim construction for “roofing or building cover material” focused on whether it would have been obvious to incorporate the lamination roll / printing process disclosed in the secondary reference to cover material having asphalt. But, by using this narrow claim construction that required asphalt, the Board ignored whether it would have been obvious to incorporate the lamination roll / printing process disclosed in the secondary reference to non-asphalt cover material. The Board concluded that Claim 1 was not obvious to use lamination rolls or printing processes on cover materials using asphalt and thus found the claims patentable (i.e., not obvious) over the cited references.

Under the broadest reasonable interpretation, roofing or building cover material would be broad enough to encompass cover material with or without asphalt. The Board had thus erred because it limited the meaning of the disputed claim terms by requiring a cover material using asphalt.

In reviewing the Board’s decision of nonobviousness, the Federal Circuit found that the Board simply did not consider the obviousness analysis in light of building cover materials that did not use asphalt. The Federal Circuit concluded that the Board erred by construing the claims to exclude such non-asphalt materials even though building cover material recited in the claim was broad enough to cover materials that do not have asphalt.

II. FEDERAL CIRCUIT’S OBVIOUSNESS ANALYSIS

With the broadest reasonable interpretation of the claim language in mind, the Federal Circuit analyzed the obviousness of the proposed combination of prior art references. Lassiter specifically taught that its process of applying nail tabs with a nozzle was applicable to building cover materials such as “covering sheets” and “Styrofoam board sheathing.” Moreover, the court found that: “Lasiter itself, by its terms, suggests that a person that a person of ordinary skill in the art would be motivated to print nail tabs on building cover materials that are not and will not be asphalt coated.”

Thus, although the Lasiter reference taught away from applying the printing process of the secondary references to an asphalt cover material, Lasiter did suggest applying the printing process disclosed in the secondary references to non-asphalt cover material such as covering sheets and Styrofoam board sheathing. The Federal Circuit thus found that one of ordinary skill in the art would be motivated to apply the printing process taught in the secondary references to the process taught in Lasiter. Hence, claim 1 was obvious.

Potential Recommendations

Fast Felt’s patent specification explained that the preferred embodiment of the invention was directed to roofing cover material with asphalt. However, it appears that the invention was broadened to encompass other applications not including asphalt. Broadening the scope of the invention’s applicability is a normal occurrence in the process of preparing a patent application. A patent attorney should identify the primary vertical market (e.g., roofing market) for the invention then carefully expand applicability of the invention to other vertical markets (e.g., building market in general) when desirable – and when permitted by the prior art.

The Owens Corning case illustrates how broadening a claimed invention’s field of use could be detrimental to the claim’s validity and make it harder to overcome an obviousness rejection. A way to mitigate invalidity attacks under these circumstances would be to consider adding an additional claim focusing on each of the more narrower fields of invention. For example, claim 1 could have been presented twice with a slight distinction between the two. A first time for roofing cover material only, and a second time for building cover material only. In this way, the litigation could have separated the scope of the claims and isolated any invalidity issues related to building cover material to its own independent claim so that the roofing cover material claim might have survived the invalidity attack and left the patent owner with some patent protection.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Quartz-IP-May-9-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

One comment so far.

Dan Hanson

November 7, 2017 01:18 pmIt seems to me the application of the Broadest Reasonable Construction in Light of the Specification standard played a non-determinative role in this case; the result would have been the same even under the so-called Phillips standard. The claims used over-broad language, and so did the specification; and the specification also indicated that the ordinary/customary meaning of “roofing or building cover material” was very broad as well.