A few months ago, a judge ordered Apple to pay the University of Wisconsin $506 million for infringing one of its tech patents. Last year, Carnegie-Mellon University won $750 million in a patent infringement lawsuit against Marvell Technology Group. With such big-money patent cases in the news, you might think that owning a patent can create a major windfall of profit for universities. While this has proven true for a handful of institutions, the truth is that most universities actually make little or no money from licensing the inventions they produce.

A few months ago, a judge ordered Apple to pay the University of Wisconsin $506 million for infringing one of its tech patents. Last year, Carnegie-Mellon University won $750 million in a patent infringement lawsuit against Marvell Technology Group. With such big-money patent cases in the news, you might think that owning a patent can create a major windfall of profit for universities. While this has proven true for a handful of institutions, the truth is that most universities actually make little or no money from licensing the inventions they produce.

What’s in a number?

Though reports are often published listing top schools based on the number of patents they hold, this metric says nothing about the financial return or value of those patents. For example, in 2014 the Intellectual Property Owners Association (IPO) ranked the University of California (UC) as #1 on their list of Top 100 Worldwide Universities. This ranking was based on the 453 patents UC had under its belt – nearly twice as many as the next spot on the list (Massachusetts Institute of Technology with 275 patents) and over five times as many as Northwestern University, which ranked #22 with only 84 patents. The reality, however, was that Northwestern’s 84 patents were worth much more than UC’s 453 patents. As Bloomberg reports, the Chicago-based school earned $361 million in patent licensing royalties the same year that UC earned $109 million.

An exclusive club

In 2012, the Brookings Institute reported that just 16 universities accounted for 70% of all university licensing fees. These schools belong to a stable and exclusive club. In the last decade, just 37 universities have been able to make their way into the Top 20 of licensing revenue.

For the thousands of other universities in the world, investing in patent licensing is a very different story. In an average of 87% of universities over the last 20 years, the administrative costs of licensing patents through a dedicated Technology Transfer Office (TTO) were greater than the money that came in from licensing. Thus, while the payoff can be impressive, the risks of falling short are very high.

Why universities are allowed to own publicly funded inventions

Just over half of university research funding comes from the U.S. federal government. It used to be closer to 70% back in 1972, but the percentage keeps dropping – and it’s not due to a reduction in spending. Rather, universities are increasingly relying on private and corporate funding. Still, considering the billions of dollars the government contributes, it may seem odd that universities are allowed to own and patent innovations paid for by taxpayer dollars. It didn’t used to be this way.

Prior to the Patent and Trademark Law Amendments Act of 1980 — popularly known as the Bayh-Dole Act for Senators Birch Bayh and Robert Dole — patents from publicly funded research were owned by the U.S. government. The government did very little with the patents, often leaving them in limbo, unused. The purpose of the Bayh-Dole act was to grant research institutions and scientists the ability to own inventions, along with an obligation to do their best to exploit and monetize them. The idea was that this arrangement would lead more naturally to the effective dissemination of innovations.

According to law firm Goodwin, the law has been successful, and is credited with the creation of over 10,000 startups, at least 200 drugs and vaccines, and the contribution of over $500 billion to the U.S. economy.

Where university patents often wind up

When a university patents something that’s truly important, it can be difficult to find a licensee. For one thing, a discovery may be just the first breakthrough step in what can be a long development process. It could be years – and numerous other patents – before the university sees a return on its investment. Joy Goswami, assistant director of the TTO at the University of Delaware in Newark told Nature that only about 5% of university patents are ever successfully licensed.

Though the point of public funding is to promote public interest by supporting the creation of new businesses built around patents, the reality is that schools often wind up licensing their IP portfolios just to recoup their costs.

Changing IP strategies

The primary finding in the Brookings Institute report is that universities, to maximize their profits, should move away from TTOs and toward startups. Profits can be significant if university startups are granted access to the university’s patents for the purposes of administering, licensing, and otherwise exploiting their IP.

Not everyone agrees with this conclusion though. Bayh-Dole expert Joseph Allen believes universities should not get rid of their TTOs – they just need to add startups. He said, “If you’re managing a portfolio of early stage university inventions, a small subset will have some commercial potential. An even smaller subset could be the basis for forming a new company… Telling universities that they should primarily focus on inventions that could form start-up companies, or that they should not use exclusive licenses is like telling a carpenter that they can use a hammer but not a saw.”

It’s not all about the money

The odds of making a massive amount of money from a patent are small. Stanford, for example, has disclosed 10,000 inventions since 1970 and only 3 of them have generated multimillion dollar licenses.

Even without a spectacular financial payoff, doing meaningful research can be an important part of an educational institution’s identity. After all, research is an important educational complement to classroom instruction. Thus, for most universities, making money from the resulting patents is just icing on the cake.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

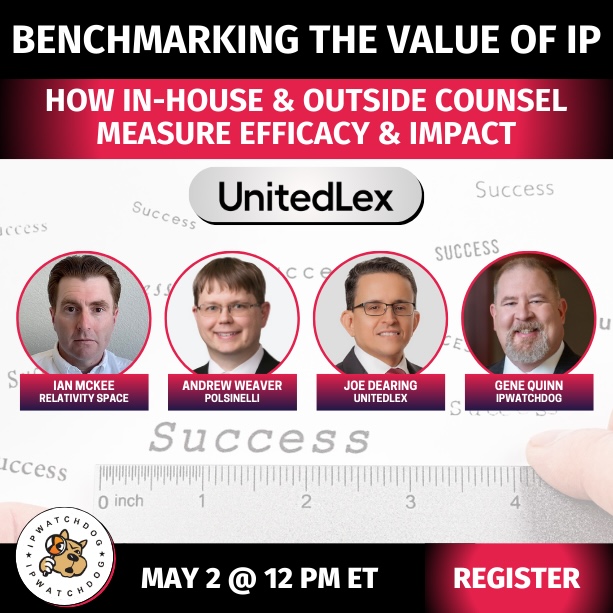

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Quartz-IP-May-9-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

3 comments so far.

Gene Quinn

November 21, 2017 04:36 pmBill-

I don’t believe that is correct. Universities would still obtain patents, and there was still (ostensibly) the ability to license from a University, but the amount of red tape required made it functionally impossible in reality to license University technology. In fact, there were zero drugs to come to market as the result of university research prior to Bayh-Dole and since Bayh-Dole the number is 200+.

Bayh-Dole expert Joe Allen wrote that after passage of Bayh-Dole 200 new drugs and vaccines were created when no drugs were developed from federal funding under previous patent policy. See:

https://ipwatchdog.com/2016/03/01/winning-the-patent-policy-wars/id=66649/

Bill Edens

November 21, 2017 04:13 pmI was under the impression that prior to the Bayh-Dole Act that there was little incentive to patent discoveries, so rather than sitting in limbo they were just never patented. Which meant that they were available for use by all. Which in tern lead to the discoveries making their ways inexpensively into all sorts of products and services. Perhaps my understanding is based on too much anecdotal information.

Chris Gallagher

November 20, 2017 02:54 pmAdam correctly quotes Joe Allen’s earlier post :

Telling universities that they should primarily focus on inventions that could form start-up companies, or that they should not use exclusive licenses is like telling a carpenter that they can use a hammer but not a saw.” https://ipwatchdog.com/2014/01/27/does-university-patent-licensing-pay-off/id=47655/

Bayh-Dole was intended to facilitate the commercialization of federally-funded basic research to convert it the public’s benefit. Prior to its 1980 passage, promising basic research was gathering dust on government shelves rather than being refined and transferred into the private sector where its promising benefits could be converted into public availability after applied research and prudent private capital investment. TTO patent holders are best suited to successfully select and harness such support. As Joe Allen’s post above conclusively demonstrates, the record proves it. University TTO patent holders and their commercialization partners are positioned to decide what commercialization method or structure is best suited to expeditiously execute that now long achieved congressional objective .