Robin Thicke

Some IP commentators love to hate the Blurred Lines music copyright decision. A primary critique has stoked unnecessary fear in musicians that the decision blurs the line between protectable expression and unprotectable style or genre. Much of the animosity, however, is based on misunderstanding or misconstruing the law or facts. This post clarifies this aspect of the case to show why the district court decision was reasonable and should be affirmed in the current appeal at the Ninth Circuit.

The pop star composers of Blurred Lines—Pharrell Williams and Robin Thicke—brought a pre-emptive declaratory judgment action against the family of late soul superstar Marvin Gaye, after the latter raised concerns about the similarity of the song to Gaye’s classic Got To Give It Up. No. 13-cv-06004 JAK (C.D. Cal. 2015). The district court excluded the recording of Got To Give It Up on the basis that only the “lead sheet” used to register the song with the Copyright Office, or published sheet music of it, was admissible as evidence of Gaye’s composition. Despite this limitation, supporters of Williams et al have argued that the court’s evidentiary rulings and jury instructions were still improper and the verdict should be overturned. Others have argued that the outcome improperly extended copyright to cover “groove,” “style,” or “genre.” I will use my own experiences as a songwriter and lawyer to explain the issues and argue that in fact the court should have allowed Gaye’s recording of the song as evidence, as Lateef Mtima, Steve Jamar, and I wrote in our amicus brief for the Institute for Intellectual Property and Social Justice (IIPSJ) in the Ninth Circuit appeal.

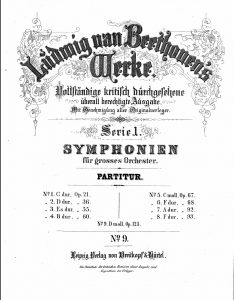

Like many popular music composers, I write songs on guitar or keyboard, with vocals, and make a rough recording to capture them. I do not use music notation as it is not that relevant for much of pop music that relies on innovative instrument timbres and off-the-beat phrasing. European music notation was not designed to express these. As the song fleshes out, I use multi-track recorders to compose and capture parts for different instruments. If I used written notation for this, I would have to write out multi-staff notation such as symphonic conductors use (see Beethoven score below).

And then I would be limited to performing/recording with musicians who could read sheets. Finally, when I record different parts myself, there is no need for charts. Today’s pop composers have taken this a step further and often establish the beats and rhythm parts—not to mention instrument timbre—as the commercial heart of a new song before adding melody lines as almost afterthoughts. While software can now generate music notation from music played on a computer-connected keyboard, this has not yet penetrated deeply into the pop composer space, in part because it is only useful for musicians who prefer to play from charts.

And then I would be limited to performing/recording with musicians who could read sheets. Finally, when I record different parts myself, there is no need for charts. Today’s pop composers have taken this a step further and often establish the beats and rhythm parts—not to mention instrument timbre—as the commercial heart of a new song before adding melody lines as almost afterthoughts. While software can now generate music notation from music played on a computer-connected keyboard, this has not yet penetrated deeply into the pop composer space, in part because it is only useful for musicians who prefer to play from charts.

Fortunately, by the time I started my music career in the 1980s, the Copyright Office allowed “aural” composers like me to submit a phonorecording of our songs—even for the music composition copyright. “Phonorecording” is a term of art in the Copyright Act meaning “material objects in which sounds . . . are fixed by any method now known or later developed, and from which the sounds can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device.” 17 U.S.C. 101. Phonorecords should not be conflated with “sound recordings” which are “works that result from the fixation of a series of musical spoken, or other sounds . . . regardless of the nature of the material objects, such as disks, tapes, or other phonorecords, in which they are embodied.” Id. Sound recording rights are noted by the (P) symbol on distributed phonorecords. The phonorecord is the material object and the sound recording is the “work” in the way that a physical book is a “copy” and the expressed fixed in it is the “work.” Music composition rights—covering the song itself regardless of who performs/records it—are denoted by the © symbol.

But for music fixed in a phonorecord, there can be two works embodied: a sound recording and a music composition. The best way to distinguish them is to think of phonorecords that are not music, such as audio books or environmental sounds (e.g., audio recording of a beach). There is only a sound recording right in these as no musical composition is being performed/recorded. The phonorecord is the physical embodiment, while the sound recording is the legal right to a particular fixed sequence of sounds, analogous to distinguishing physical embodiments from a patented invention. The analogy is imperfect, though, because the sound recording is limited to the exact electronically or mechanically captured sequence of sounds. Thus, to infringe a sound recording, I have to electronically or mechanically duplicate a phonorecord of the original. (I will use “electro-mechanical” for brevity to mean electronic or mechanical, as well as truly “electro-mechanical” hybrid processes/devices). A new recording of sounds at the same beach is not an infringement. For a music phonorecord that captures performance of an original composition, the material object serves as a fixation of that composition, as well as of the performance as a sound recording. Thus, a commercially distributed phonorecord can have both the (P) and © symbols on it to note the two different rights embodied.

The oft-misused term “sampling” is clarified by this distinction too. True sampling means electro-mechanically duplicating snippets (or “samples”) of phonorecords. Recording musicians performing the musical content of the desired passage is neither sampling nor an infringement of any sound recording right in the original phonorecord. It may be infringement of a music composition right though. Sampling came about first through the mid-20th century musique concrète movement (most famously in The Beatles’ Revolution #9). But, affordable tape recording units of the 1980s enabled artists of modest means to duplicate musical passages they liked—often “looping” them to create a longer vocal-free music base—to then overdub a vocal rap. Combined with recording the effects of “scratching” on turntables, this created the underlying sound of modern rap and hip hop. But even after some rappers could afford to record music passages fresh, they had become enamored of the evocative effect of sampling phonorecords that had instantly recognizable sounds due to the confluence of particular musicians performing at certain studios with specific equipment (e.g., mics, recording devices, mixing boards, effects)—“lightning in a bottle” that can be next to impossible to replicate in a new recording.

Beginning in 1978, aural composers like myself could record our compositions onto any phonorecord medium—including affordable cassette tapes—and then submit this to the Copyright Office with the proper form to register our © composition right. This could be a basic recording of voice and guitar, or a multitrack recording including other instrument and vocal parts. The open question remains whether a basic voice-and-guitar phonorecord would give rise to the composition right covering the fully orchestrated version of the song or just the vocal and guitar parts captured. To be safe, a composer should submit a phonorecord that includes all the parts she composed for the song.

Either way, an evidentiary problem in any later dispute is to identify which parts embodied in commercially released phonorecordings were composed, and thus protectable, by the songwriter? Like combination patents, most musical compositions should be viewed as combinations of discrete musical elements or parts. Some of these parts may be considered scenes a faire under copyright, which is loosely similar to prior art no longer covered by a valid, enforceable patent. Examples include standard blues riffs or longstanding popular chord changes. But, original musical elements can be enforceable essentially on their own. Thus, one need not copy all or even most elements of an overall multi-part composition to infringe. Simply copying a substantial portion of one element can be enough. An example would be copying famous rock riffs such as that to The Beatles’ Day Tripper or The Rolling Stones’ (Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.

But prior to 1978, aural composers had no option to submit a phonorecording to register their © composition right. Rather, there had to be a written notation. (There is anecdotal evidence that the Office in fact did allow wax cylinders or player piano rolls as deposits for registration in the early 20th century.) And even as the Copyright Office allowed for any form of writing—including sui generis systems of a composer—in practice record labels and music publishers insisted on submitting standard European notation versions for registration. Because the aural composer could not produce this, a trained scribe at the publisher would write what he thought was a reasonable approximation of the song based on listening to a phonorecord—usually with no involvement of the composer. Further, the convention of the time was to draft a bare bones “lead sheet” which included only what was perceived to be the main melody of the song (usually the lead vocal) together with chord names above the staff (e.g., “A7”). No one considered these to be complete notations of the composition, but rather they were used as placeholders to identify the work, much like the abbreviated submissions for software to the Office, or abbreviated DNA sequences to the PTO for patent applications.

The lead sheet used to register Got To Give It Up (below) was unusual because it included a key bass line that in fact was one of the clearest elements copied by Williams et al in Blurred Lines. While some critics have claimed—without evidence—that this was a “standard” scenes a faire bass line, that is hindsight bias familiar to patent experts. Gaye’s bass line influenced many later songs and thus seems standard now, but I have yet to hear a similar bass line on a phonorecord commercially released before Got To Give It Up. I will be happy to revisit my position if/when one turns up. At the same time, if this were such a standard bass line at the time, the scribe would not have taken the unusual step of specially notating it.

Critics also complain that the court allowed the Gaye family’s musicologist to submit in evidence a performance of the lead sheet that added elements not in it. This included playing the chords with an appropriate rhythmic feel given the notated bass and melody lines. The critique has little merit. When a scribe writes “A7” at the top of a bar of music, any professional musician who reads that (including me) knows they have to interpret it for rhythm. There is no notation showing what rhythm to play the chord in and there is no default “rule”; all you know is that you are playing that chord somehow during that measure. You are not even told what voicing to use, and all professional musicians know that there are multiple ways to play any given chord such as “A7,” especially on guitar. That said, an experienced musician can make an educated guess from clues such as the melody line phrasing. In Got To Give It Up, the musicologist had even more to work from because of the phrasing of the central repeating bass line. Thus, she performed the lead sheet as any other professional musician would, making necessary decisions as to rhythm of the chordal accompaniment that are inherent to the lead sheet notation and not “added” or made up elements.

The district court also allowed the song’s published sheet music to be submitted as evidence. The problem is that commercial sheet music is generally an adaptation of the actual composition to allow beginning to intermediate amateurs to perform a facsimile of the song. Pop songs are often modulated to keyboard or vocal friendly key signatures, such as C, and many elements are left out. Most importantly, the sheets are written to convey only a two-handed piano version of the song, together with the lead vocal melody line and maybe guitar chord names. They are thus an abridged version of the composition that tries to incorporate some reasonably playable elements into one part. Important bass lines, horn lines, lead guitar lines, etc. are often left out. Finally, played mechanically, these piano parts often show little musicality, as this algorithmic “performance” of Got To Give It Up’s commercial sheet music shows. Human musicians thus must also interpret such sheets to make them sound like real music.

Gaye composed in the studio. He was not trained in European notation and did not use it. He created innovative parts for different instruments and combinations of old and new elements, and performed many of them himself. Therefore, the only way to understand the full scope of a Gaye composition is to hear its phonorecording. That such phonorecords could also be commercially distributable sound recordings does not cancel out their role for him as fixations of the composition itself, just as post-1978 composers like me submitted phonorecords to register our composition rights.

Thus, the district court should have allowed the phonorecord of Got To Give It Up as evidence of the actual composition (identified and registered through the placeholder lead sheet convention of the time). That the Gaye family still won even with the exclusion of this phonorecord only underscores the validity of the district court jury verdict. Williams et al wanted the court to limit evidence to the lead vocal melody (and as performed by a new singer, not using Gaye’s voice from the original phonorecord) because they felt this was the weakest point of similarity between the two songs. Admission of the bass line and inherent rhythmic chord patterns—not to mention percussion and background vocals that Gaye composed in the original phonorecord—would show clear similarities in important elements of the songs. Thus, Williams et al unleashed proxies who tried to paint the decision and similarities as based on amorphous and unprotectable “groove,” style, or genre in the media. But that is not what either the judge, jury, or the Gaye family understood from the evidence actually presented in the courtroom. They were reasonably responding to concrete specific instrument parts that had been copied, as well as the protectable combination of them.

In sum, the verdict in Blurred Lines was supported by properly admitted courtroom evidence. The Gaye family musicologist presented a necessary and reasonable performance of the lead sheet, which the jury required because they could not be expected to read and understand the lead sheet themselves. In fact, the judge should have also admitted Gaye’s phonorecord as well—especially as the Office’s rule was changed the year after the song was released—which would only strengthen the family’s case.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

2 comments so far.

Lost In Norway

January 10, 2018 01:27 amGreat article. It changed my mind on the ruling. Thanks.

Gabriel Hogan

January 9, 2018 01:58 pmFirst good, clear argument I have read on this. Thank you.