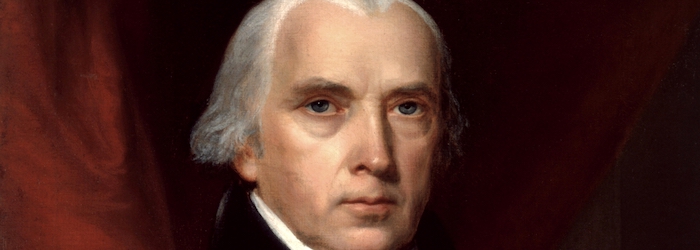

James Madison — the fourth President of the United States and the father of the U.S. Constitution — wrote the usefulness of the power granted to Congress in Art. I, Sec. 8, Clause 8 to award both patents and copyrights will scarcely be questioned.

Congressional power to grant both patents and copyrights is derived from Art. I, Sec. 8, Clause 8 of the United States Constitution, the so-called Intellectual Property Clause. To patent attorneys Art. I, Sec. 8, Clause 8, will forever be known as the Patent Clause. For attorneys specializing in copyright law this clause is known as the Copyright Clause. It is probably best to simply recognize that our founding fathers deemed intellectual property rights so vitally important to the success and stability of our new country that these rights were written into the Constitution, a document not generally known for its length and specificity.

The Clause is short and direct. Congress has the power to “promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.”

As James Madison — the fourth President of the United States and the father of the U.S. Constitution — stated at the beginning of Federalist Paper No. 43, that the usefulness of the power granted to Congress in Art. I, Sec. 8, Clause 8 to award both patents and copyrights “will scarcely be questioned.” The entire passage reads:

The utility of this power will scarcely be questioned. The copyright of authors has been solemnly adjudged, in Great Britain, to be a right of common law. The right to useful inventions seems with equal reason to belong to the inventors.

This is the only reference to Art. I, Sec. 8, Clause 8 in any of the Federalist Papers. Indeed, very little is known about what the Framers of the Constitution thought about patents and copyrights because, as Madison succinctly explained, the need for both patents and copyrights was considered self evident and without question by the Framers.

Professor Melville Nimmer’s treatise on copyright also explains:

When the framers of the United States Constitution met in Philadelphia to consider which powers might best be entrusted to the national government, there appears to have been virtual unanimity in determining that copyright should be included within the federal sphere. Although the committee proceedings that considered the copyright clause were conducted in secret, it is known that the final form of the clause was adopted without debate.

1 Melville B. Nimmer & David Nimmer, Nimmer on Copyrights, § 1.01[A] (2000).

Congress has been exercising its prerogative to grant both patents and copyrights since the very beginning of U.S. history. Indeed, on January 8, 1790, President Washington delivered his first State of the Union speech to Congress. In this first ever State of the Union, only months after the ratification of the Constitution and assuming Office, President Washington asked Congress to exercise its powers granted in the Constitution to enact a patent statute.

Washington’s State of the Union was a mere 1,096 words, yet he devoted this passage to patents:

The advancement of agriculture, commerce, and manufactures by all proper means will not, I trust, need recommendation; but I can not forbear intimating to you the expediency of giving effectual encouragement as well to the introduction of new and useful inventions from abroad as to the exertions of skill and genius in producing them at home, and of facilitating the intercourse between the distant parts of our country by a due attention to the post-office and post-roads.

Congress responded quickly. The first Patent Act was the third law ever passed by Congress. Indeed, the first Patent Act, the Patent Act of 1790, was signed into law on April 10, 1790, just several months after President Washington asked Congress to take action. See The Day that Changed the World: April 10, 1790.

Following the Patent Act of 1790, the Congress soon delivered the first copyright laws. The Copyright Act of 1970 was approved by Congress on May 31, 1790.

There is little doubt that patents were viewed by both Washington and Madison to be centrally important to the success of the new United States. The importance is only underscored by the fact that the only use of the word “right” in the U.S. Constitution is in reference to authors and inventors being granted exclusive rights. In other words, the only “rights” mentioned in the Constitution are patents and copyrights.

The ultimate decision with respect to whether to grant protection in either copyrights or patents is left to the sound discretion of Congress. Nothing in the Constitution requires that Congress actually award protection in the form of copyrights and/or patents. In this regard the United States Supreme Court has explained:

While the area in which Congress many act is broad, the enabling provision of Clause 8 does not require that Congress act in regard to all categories of materials which meet the constitutional definitions. Rather, whether any specific category of “Writings” is to be brought within the purview of the federal statutory scheme is left to the discretion of the Congress. The history of federal copyright statutes indicates that the congressional determination to consider specific classes of writings is dependent, not only on the character of the writing, but also on the commercial importance of the product to the national economy.

Goldstein v. California, 412 U.S. 546, 562 (1973). Nevertheless, Congress has consistently chosen to grant both patents and copyrights ever since the enactment of the first copyright statute in 1790, and the first patent statute, also in 1790.

The reason the U.S. Constitution grants Congress the power to legislate in the area of intellectual property is to promote innovation and the arts. It is interesting to note, however, that while today we speak of innovations as relating to patents and the arts relating to the dominion of copyright law, the words “science” and “useful arts” as included in Art. I, Sec. 8, Clause 8 do not carry the same meaning they do today. It is interesting to note that the word “science” in the Clause refers to protection of copyrightable subject matter and the term “useful arts” refers to the protection of patentable inventions.

Giles Sutherland Rich, the father of the 1952 Patent Act, explained this in an address at Franklin Pierce Law Center in 1994. Judge Giles Sutherland Rich explained:

[O]ver a time of two centuries, the meaning of even common words may change. “Science” as we use it today does not have the connotation it did in 1787 when it referred to knowledge in general, in all fields of knowledge. What we mean today by “science” was then called natural philosophy. It was quite clearly intended by the authors of the Constitution that copyright, not patents, was intended to promote science, and the province of rights granted to inventors respecting their “Discoveries” was to promote the “useful Arts.” Yet we find never ending references in the opinions of Federal Judges, perhaps looking at the patent clause for the first time, and taking what is there written at face value, to the promotion of “Science and the useful Arts” by the issuance of patents.

35 IDEA 1, 2 (1994). Notwithstanding the evolution of the Constitutional language, both the patent and copyright laws promote this progress by extending to patent and copyright owners the right to exclude others.

The patent laws offer this exclusive right for a limited time as an incentive to inventors, entrepreneurs and corporations to engage in research and development, to spend the time, energy and capital resources necessary to create useful inventions; which will hopefully have a positive effect on society through the introduction of new products and processes of manufacture into the economy, including life saving treatments and cures. See Kewanee Oil Co. v. Bicron Corp., 416 U.S. 470, 480 (1974)(patents provide “an incentive to inventors to risk the often enormous costs… [benefiting] “society through the introduction of new products and processes of manufacture into the economy, and the emanations by way of increased employment and better lives for our citizens.”); see also Universal Oil Products Co. v. Global Oil Refining Co., 322 U.S. 471, 484 (1944)(“As a reward for inventions and to encourage their disclosure, the United States offers a seventeen-year monopoly to an inventor who refrains from keeping his invention a trade secret.”)

Likewise, the copyright laws offer exclusive rights for a limited time as an incentive to authors and artists to create. The purpose of providing authors with copyright protection is to stimulate activity in the arts, which will in turn provide intellectual enrichment for society. This utilitarian goal is achieved by permitting authors to reap the rewards of their creative efforts. See also Mazer v. Stein, 347 U.S. 201, 219 (1954) (“The economic philosophy behind the clause empowering Congress to grant patents and copyrights is the conviction that encouragement of individual effort by personal gain is the best way to advance public welfare through the talents of authors and inventors in ‘Science and useful Arts.’”)

Given that today’s business world is increasingly based on a company’s ability to innovate and create, the the basic economic truth that without protections free-riders will take what others have created, acquire intangible assets in the form of both copyrights and patents are critically important.

The Constitutional goal of stimulating creativity and invention has been wildly successful throughout U.S. history. Nevertheless, in recent years innovators have struggled to gain and keep the patent protection they need, thanks to the creation of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board and several Supreme Court decisions on patent eligibility that while bad have been interpreted by lower courts in a way that has hamstrung the software and biotechnology industries. Meanwhile, authors and artists have struggled with rampant and flagrant infringements enabled by the digital era, often with no recourse being available.

The Framers of the Constitution, including Madison and Washington, once viewed the need for patents and copyrights as self-evident. That truth should be remembered on this President’s day, and taken to heart by our leaders in Washington, D.C.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Quartz-IP-May-9-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

9 comments so far.

Night Writer

February 20, 2018 11:58 amReally great job Gene. It is so important that people have time to spend to counteract people like Mark Lemley, who Stanford pays to burn down the patent system.

angry dude

February 20, 2018 10:09 amSteve L@6

“The modern system does not fulfill the constitutional promise for Inventors while it does for Authors, and if it does for both then why such a stark comparison?”

You know why, don’t you, dude ?

Corporate power and greed

There are Disney and Hollywood pushing for stronger copyright laws and there are googles apples and amazons pushing for unenforceable US patents

Constitution ??

Teach it to scotus and congress critters cause they are the ones who care the least

Steve L

February 20, 2018 09:54 amI wrote this (below) as a comment to an article earlier this month, but it is particularly apt to Gene’s article today. Patents are a right and the Constitutional promise for them has not been fulfilled.

IP laws have been very good to the Copyright/Trademark area, but not so much for Patent law. Artists and Inventors are both cited in the Constitution (Article 1, Section 8, Clause 8), but equal treatment between the two has not been ushered. Copyright’s are protected 70 plus years vs 20 for inventions and can be enforced with substantial copyright specific criminal penalties (nothing like that for inventions). The practical cost of obtaining copyright/trademark protections for both USPTO fees and Attorney costs are a fraction of that for Patents and the same could be said for defending them.

Patent law is struggling with an arcane system that does a very poor job of making the court system accessible to average inventors. When a patented product is blatantly knocked off (aka, copied), all bets are off that the inventor will ever get justice. Defending copyright/trademark is much easier and the paths are much clearer.

Micky Mouse (Disney) has been the most successful political lobbyist ever! The comparisons between Copyright/Trademark vs Patent should cause us to ask, has the constitutional promise been fulfilled for Patent law? I say not, it is time for a paradigm shift in improving the inventors protections and we should pursue more and more constitutional arguments. The modern system does not fulfill the constitutional promise for Inventors while it does for Authors, and if it does for both then why such a stark comparison?

RespectPatents

February 20, 2018 09:21 amPaul,

Capitalized or not, “right” in Art. I, Sec. 8, Clause 8 is the ONLY place used within the body/actual text of the Constitution or Bill Rights (not headings). The importance is without question. Parties that question if a patent system is even needed today should leave the country. It is part of the genius design of the Constitution.

Anon

February 20, 2018 08:10 amBenny,

Try to remember that some terms are NOT dependent on “normal” accepted use.

Try to remember that some terms carry a definite LEGAL notion of “normal” accepted use.

If you do so, then you may find yourself more able to deal with the feelings that undergird your comment.

Benny

February 20, 2018 05:36 am“the copyright laws offer exclusive rights for a limited time ”

That is stretching the meaning of the word “limited” beyond its’ normal accepted use.

Anon

February 19, 2018 03:03 pmPaul,

Your view of “Right” carries with it one (not so minor) item: the difference between an inchoate Right and a legal right, fully matured under the law.

What the Constitutional Clause is, IS a delegation of authority among the various branches of the government, and it is fully within the single legislative branch (as opposed to the judicial or executive branches to set the actual ground rules for the “race” for a patent (as a granted legal property, contrasted with the notion of the inchoate right).

Your view is a little bit crabbed, and “crunches” the concept of “withdrawal” because the item is a grant. In other words, your words are not correct, and the legal meaning is a bit more nuanced.

Anon

February 19, 2018 02:57 pmIt is NOT a coincidence that Madison also warned of a judiciary that was too powerful (mirroring how the current Supreme Court acts as if “Supreme” places them above the Constitution, the Separation of Powers, and the notion of a court of limited powers (notably, the current case or controversy element as opposed to subjective, prospective notions of what may happen).

Paul Morinville

February 19, 2018 02:42 pmIn Article 1, Section 8, Clause 8, the word Right is capitalized. Words in the Constitution are capitalized for a reason. It is the only place in the Constitution where the word Right is used and that means it is actually a Right just like Free Speech, Religion, etc. are Rights.

The courts, Congress and the Administration have it completely backwards. They consider that Right to be granted by the government, not the other way around. If it is granted by the government, the government can take it away. But that is not how it works and nor how it should work.

The People granted Congress power to protect our Rights in the Constitution. Our Rights exist even without the government. Rights are granted by God and hang atop of the government. Which means that the government has no power to grant any Rights… the only power the government has is to protect our Rights.

Therefore a patent is a government document used to protect a Right to an invention that already exists as a Right even without the government.

The government has strayed so far into socialism … it is shamefully ignorant.