On February 2, 2018, in Sophos Inc. v. RPost Holding, Inc., Judge Denise Casper became the latest judge to declare a case “exceptional” under 35 U.S.C. § 285 and award the declaratory judgment plaintiff, Sophos, the opportunity to recover its attorneys’ fees. The court’s decision in Sophos comes as the four year anniversary of the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Octane Fitness v. ICON Health & Fitness rapidly approaches. After Octane Fitness, many predicted a large uptick in the number of fee-shifting motions filed and their success rate in patent cases. This article explores the fallout from Octane Fitness after four years on the books and any trends that have emerged in the courts.

On February 2, 2018, in Sophos Inc. v. RPost Holding, Inc., Judge Denise Casper became the latest judge to declare a case “exceptional” under 35 U.S.C. § 285 and award the declaratory judgment plaintiff, Sophos, the opportunity to recover its attorneys’ fees. The court’s decision in Sophos comes as the four year anniversary of the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Octane Fitness v. ICON Health & Fitness rapidly approaches. After Octane Fitness, many predicted a large uptick in the number of fee-shifting motions filed and their success rate in patent cases. This article explores the fallout from Octane Fitness after four years on the books and any trends that have emerged in the courts.

The overall numbers

Since Octane Fitness issued on April 29, 2014, district courts have been asked to award attorneys’ fees in patent cases nearly 420 times. Overall, district courts have agreed approximately thirty-three percent of the time.

In the last four years, the vast majority of section 285 motions—over 75%—have been filed by accused infringers. That makes sense. An accused infringer simply has more opportunities to “prevail” over the course of any given case. Procedurally, accused infringers have filed fees’ motions after winning by motion to dismiss, judgment on the pleadings, voluntary dismissal, summary judgment, trial, and even post-trial motion practice. Overall, accused infringers slightly underperform the national average with a success rate on section 285 motions of just under 30%.

For their part, patent holders typically need to take cases further (i.e., to the end) in order to “prevail.” As a result, the bulk of patent holder motions come after a finding of willful infringement (37%) or after the accused infringer defaults (33%). It total, patent holders prevail on exceptional-case motions over 46% of the time, but that percentage drops to 34% if adjusted to remove cases where the defendant has defaulted.

It is notable that a finding of willful infringement does not automatically mean a case will be deemed exceptional. Quite the opposite. On average, a finding of willful infringement only results in an exceptional case finding 51% of the time. Without a willfulness finding, however, success rates for patent holders on section 285 motions falls precipitously to only 14%.

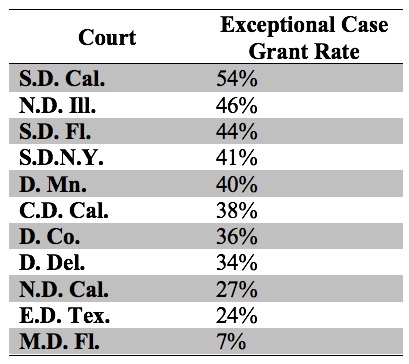

By the courts

There is no surprise which courts grapple with section 285 the most often after Octane Fitness. Nearly half of all exceptional-case decisions come from the five courts with the most active patent dockets: Eastern District of Texas (12%); Central District of California (11%); Northern District of California (11%); Delaware (9%); and Southern District of New York (4%). Table 1 provides the overall grant-rate for section 285 motions in districts with more than ten reported decisions. The District of Massachusetts, where the Sophos case was pending, falls squarely in line with the national average post-Octane Fitness, with a grant rate of 33%.

Trends

A centerpiece of Octane Fitness was the Supreme Court’s admonition that the then-operative Federal Circuit test for exceptionality “superimpose[d] an inflexible framework onto statutory text that is inherently flexible.” The Court reinforced that there was no precise rule or formula for evaluating section 285 motions in patent cases. As a result, district courts were directed to evaluate each case on its own, considering the totality of the circumstances. Such a flexible, case-by-case approach makes it difficult to tease trends out of the hundreds of decisions that have issued since Octane Fitness. Nevertheless, there are some basic conclusions and key themes that rise to the surface.

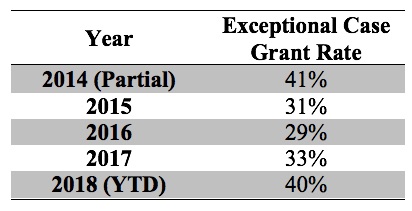

The Numbers. Quantitatively, the overall number of exceptional case decisions trended slightly downward in 2017, falling from an average of 9.5 decisions per month in each of 2015 and 2016 to 8.5 decisions per month in 2017. After an initial spike in grant rates, however, parties’ overall success rate has remained relatively flat in the last three years. (Table 2).

Showing Up Empty Handed

To the extent there is a unifying theme in the district court decisions since Octane Fitness, it is “winning alone is not enough.” A mere disagreement on the merits—whether it be claim construction, infringement or invalidity—will rarely, if ever, result in fee-shifting, especially if the losing party advances a reasonable (even if weak or worse “ill advised”) argument that was supported by a minimum quantum of evidence or law. Courts, however, are much less forgiving when parties refuse to engage on essential elements of the case. In Sophos, for example, the court found that the patent holder “failed to provide any support in the record for a number of positions it took at summary judgment.”

These types of deficiencies manifest most frequently after an accused infringer prevails on a non-infringement defense and/or the patent holder fails to stipulate to non-infringement after an adverse claim construction ruling. A corollary to this trend is that courts have limited tolerance for last-minute changes in case theories, particularly when the shifting theories are apparent to the court, such as during summary judgment.

Defeat Before the Patent Office

In cases where the accused infringer “prevailed” because of something (i.e., invalidation) that occurred in the Patent Office, courts have almost universally rejected bids for fee shifting. But the exception is also worth noting. Courts have awarded fees in cases where the patent holder was perceived to aggressively pursue the infringement case without regard to the proceedings before the Patent Office.

Non-Practicing Entities

Courts appear to give a varying weight to the business practices of patent holders. In one egregious case—where the patent owner filed nearly 500 lawsuits against small companies, settled most for well less than the cost of motion to dismiss, and dismissed those cases where the defendant mounted any form of merits challenge—the court awarded attorneys’ fees to deter and discourage exploitative litigation by patentees who are uninterested in testing the merits. The more common trend, however, is for courts to—at least nominally—declined to draw adverse inferences based on a patent holder’s licensing activity. The Sophos matter is again illustrative. There, the court chose to “put[] aside Sophos’ contention that RPost has engaged in baseless litigation against other entities in similar cases” in reaching its decision that the case was “exceptional.”

Litigation Misconduct

When faced with a motion for attorneys’ fees, courts are generally more willing to engage on the substantive strengths of the party’s positions rather than the tactics used to litigate the case. More often than not, the prevailing party’s allegations of litigation misconduct collapse into the “substantive strength” inquiry. Aggressively litigating an objectively weak case is, after all, a form of litigation misconduct. Aside from that, courts appear reluctant to call balls-and-strikes on every rule infraction over the course of a multi-year patent case. As with all generalities, however, there are exceptions where, e.g., a party fails to engage in the litigation process, engages in discovery abuses, violates a court order, or inexplicably withholds relevant discovery (or theories of the case) until the last possible minute.

Pre-Litigation Diligence or Lack Thereof

A noticeable subset of decisions granting attorneys’ fees to accused infringers involve situations where the court comes to the conclusion that the patent holder should have known better before bringing the lawsuit. These cases come in many flavors. For example, the infringement theory was facially baseless or the patent was so obviously invalid under 35 U.S.C. § 101. But those cases are few and far between. (In fact, courts deny attorneys’ fees motion more often than not after successful § 101 challenges at the pleadings stage.) The more typical scenario seems to arise when the accused infringer prevails on a license or standing defense. There, courts appear more willing to fault patent holders for not investigating ownership or the licensing status of the asserted patents—information that is unquestionably known (or knowable) to the patent holder before filing suit.

Conclusion

Four years after Octane Fitness, the Supreme Court should be satisfied that its decision has had the intended effect. Exceptional case determinations remain the exception, but not as elusive as they once were. District courts have embraced the discretion and flexibility afforded them by Octane Fitness. There is no rule or formula to fee shifting in patent cases, but after Octane Fitness, litigants on both sides are well-advised to perform an honest gut-check of their case from time to time.

Methodology: The statistics presented above were compiled by running a search on Docket Navigator® for all decisions either granting or denying requests for attorneys’ fees. The entries were reviewed and classified. Certain adjustments were made to remove duplicative hits, ancillary decisions, or fee awards under other authorities (such as Fed. R. Civ. P. 11). Partial grants were treated as “grants.”

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

3 comments so far.

PTO-Indentured

February 26, 2018 12:55 pmCare to also indicate the percentage of these cases granting ‘exceptional’ attorneys fees — resulting from AIA ‘influenced’ rule-making (‘law’)?

AIA’s impact on making so many of our U.S. patents defenseless, by intentionally and substantially weakening them in post-grant, was the perfect setup for challengers to claim ‘all fees are payable and due’ because the PTO has proven that the patentee ‘exceptionally’ brought forth a patent shown to be easily invalidated. Check please!

Bob Taylor

February 26, 2018 11:56 amVery interesting article. Thanks to the authors.

This tends to confirm that courts are using restraint in applying Section 285, which we would have expected from the word itself. I would like to have seen the first chart disaggregated as between patent owners and accused infringers.

Curious

February 25, 2018 03:36 pmI guess that mirrors today’s society’s belief that nearly everyone is “exceptional.”

God forbid that a person (or a case) is merely “average.”