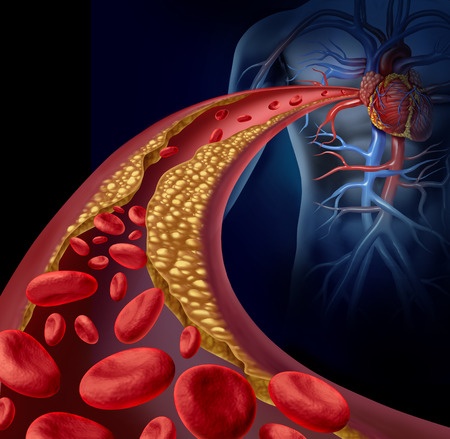

On February 28th, a group of six patent law professors filed an amicus brief with the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Cleveland Clinic v. True Health Diagnostics. The professors’ brief urges the Federal Circuit to reverse a finding by the lower court invalidating patents asserted by Cleveland Clinic covering diagnostic methods for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. According to the brief, the district court’s invalidation of Cleveland Clinic’s patents represents an improper application of 35 U.S.C. § 101, the basic threshold statute governing the patentability of inventions.

On February 28th, a group of six patent law professors filed an amicus brief with the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Cleveland Clinic v. True Health Diagnostics. The professors’ brief urges the Federal Circuit to reverse a finding by the lower court invalidating patents asserted by Cleveland Clinic covering diagnostic methods for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. According to the brief, the district court’s invalidation of Cleveland Clinic’s patents represents an improper application of 35 U.S.C. § 101, the basic threshold statute governing the patentability of inventions.

“Innovation in improving the assessment of a patient’s risk of developing cardiovascular disease is an invention that the patent system is designed to promote, and thus it should be eligible for patent protection,” the professors’ brief argues. Despite the U.S. Supreme Court’s recognition that the Section 101 threshold test should allow broad scope of patentable subject matter, district courts have been using statements from Supreme Court cases like Alice v. CLS Bank and Mayo v. Prometheus Labs out of their proper context and construe claim elements in highly generalized terms. “Thus, as happened in this case, a district court all too often merely asserts a conclusory finding that the claim— actually, specific elements dissected out of the claim as a whole—covers ineligible laws of nature or abstract ideas.”

Cleveland Clinic’s appeal to the Federal Circuit from the Eastern District of Virginia comes after the district court entered a final judgment last October which dismissed both counts from an amended complaint filed by Cleveland Clinic last February. That amended complaint alleged that blood tests for detecting levels of myeloperoxidase (MPO), which indicates inflammation related to cardiovascular disease, infringed on two patents held by Cleveland Clinic:

- U.S. Patent No. 9575065, titled Myeloperoxidase, a Risk Indicator for Cardiovascular Disease. Issued last February, it claims a method of detecting elevated MPO mass in a patient sample by obtaining a plasma sample from a patient and detecting elevated MPO mass in the sample by contacting the sample with anti-MPO antibodies and detecting their interactions.

- U.S. Patent No. 9581597, same title as the ‘065 patent. Also issued last February, it claims a method for identifying elevated MPO levels in a patient’s plasma sample with the use of spectrophotometric detection means. The work described both by this patent and the ‘065 patent were supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

In a memorandum opinion filed last August in Eastern Virginia, the district court found that these two patents from the amended complaint, as well as a third patent asserted elsewhere by Cleveland Clinic, were invalid for claiming unpatentable subject matter under Section 101. Such a finding was issued by the Eastern Virginia court after the Federal Circuit decided an earlier appeal last June where it found the three Cleveland Clinic patents to be invalid. After that Federal Circuit decision came out, defendant True Health made a motion to reconsider Cleveland Clinic’s patent infringement allegations without the need for additional factual discovery.

“Evaluating the technological context of an invention, especially when assessing whether someone has engaged in an inventive step over what was routine or ordinary in the prior art, is a factual inquiry,” the law professors’ brief argues. “Thus, the proper understanding of § 101 is that it is a legal question with underlying questions of fact that normally require proper resolution before declaring a patent claim ineligible under § 101.” Amici cite to the Supreme Court’s 2015 decision in Teva v. Sandoz to argue that SCOTUS has previously held that claim construction is a question of law with factual underpinnings. The brief also cites to a series of recent Federal Circuit cases to argue that the CAFC has also recognized the importance of factual questions underlying patentability requirements, including Akzo Nobel Coatings v. Dow Chemical and Alcon Research v. Barr Labs.

The dismissal of patent claims under Section 101 isn’t suitable for a resolution on the pleadings because of this importance of making a factual inquiry on the claims. This is a point that was recently reinforced by the Federal Circuit in its February decision in Aatrix Software v. Green Shades Software. In that case, the Federal Circuit reversed a Section 101 invalidity finding issued by the district court after finding that the lower court erred in not considering an amended complaint filed by plaintiff Aatrix which, if taken as factually true, would have established the inventive concept claimed by the patents.

The Cleveland Clinic case is just one example of a district court misapplying the patentability framework laid out by Alice and Mayo, according to the law professors. The professors note how the Supreme Court stated in both of those decisions that there are potential harms flowing from unduly restricting subject matter eligibility.

“Patent claims on diagnostic methods, including the specialized laboratory methods at issue here, present a particularly salient concern. Such claims are easy to analytically dissect and overgeneralize into individual foundational laws of nature or natural phenomenon, or restate at such a high level of generalization to be regarded as conventionally-known techniques in the art. That is not because such inventions comprise laws of nature or natural phenomena themselves, but because all diagnostic method claims seek to discover information about a subject, including those seeking to diagnose conditions in humans.”

If patents such as the ones asserted by Cleveland Clinic continue to be held invalid under the Alice/Mayo framework, the law professors argue that it will result in restricted innovation from biotech and pharmaceutical firms, especially the development of new scientific and therapeutic applications of either natural products or processes that incorporate natural phenomena. This threat to medical research is only exacerbated by the comparatively high research and development costs and long time-horizons such firms face in developing new medical treatments.

The six law professors included as amici in this brief are Walter Matystik, associate provost and adjunct professor at Manhattan College; Adam Mossoff, professor of law at George Mason University’s Antonin Scalia School of Law; Kristen Osenga, professor of law at University of Richmond School of Law; Michael Risch, professor of law at Villanova University School of Law; Ted Sichelman, professor of law at University of San Diego School of Law; and David O. Taylor, associate professor of law at SMU Dedman School of Law.

Image Source 123rf.com

Image ID : 26711342

Copyright : lightwise

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[[Advertisement]]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-1.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

One comment so far.

B

March 31, 2018 10:10 pmProfessor Mossoff et al. wrote a brilliant amici brief.