In Exergen Corporation v. Kaz USA, No. 16-2315 (March 8, 2018), the Federal Circuit, in a split non-precedential opinion, affirmed a holding that Exergen’s claims directed to methods and apparatuses for detecting core body temperature were directed to patentable subject matter under 35 U.S.C. § 101. The Federal Circuit’s decision, like many of its recent § 101 decisions, raises many interesting issues, and we briefly address two of them.

In Exergen Corporation v. Kaz USA, No. 16-2315 (March 8, 2018), the Federal Circuit, in a split non-precedential opinion, affirmed a holding that Exergen’s claims directed to methods and apparatuses for detecting core body temperature were directed to patentable subject matter under 35 U.S.C. § 101. The Federal Circuit’s decision, like many of its recent § 101 decisions, raises many interesting issues, and we briefly address two of them.

Legal Background

Anyone who “invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof” may obtain a patent. 35 U.S.C. § 101. However, because patents cannot monopolize the “building blocks of human ingenuity,” claims directed to laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas are not patentable. Alice Corp. Pty. v. CLS Bank Int’l, 134 S.Ct. 2347, 2354 (2014). In Mayo Collaborative Services. v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., 566 U.S. 66 (2012), and again in Alice, the Supreme Court provided a two-step framework for determining whether a claim is invalid under § 101. In step one, courts determine whether the claims are directed toward a patent-ineligible concept. If so, courts consider, in step two, whether the claims include additional elements that provide an “inventive concept” that transforms the claimed invention into a patent-eligible application.

Claiming well-understood, routine, or conventional activities will not make a claim “inventive” under step two. For example, the claims at issue in Mayo, which were directed to optimizing the dose a drug by measuring its metabolite, were invalid because they did nothing more than “tell a doctor about the relevant natural laws” that determine an optimal dosage, and the claimed steps of measuring the metabolite and giving the drug were routine and conventional. In Ariosa Diagnostics, Inc. v. Sequenom, Inc., 788 F.3d 1371 (Fed. Cir. 2015), a method for isolating paternally inherited fetal DNA from maternal blood serum or plasma was invalid because the existence of such DNA in the serum or plasma was an unpatentable natural phenomenon, and the claims did nothing but apply conventional techniques to isolate that DNA. Similarly, in Cleveland Clinic Foundation v. True Health Diagnostics LLC, 859 F.3d 1352 (Fed. Cir. 2017), the court invalidated a patent directed to a method of determining the risk of cardiovascular disease by measuring the quantity of myeloperoxidase (MPO) in the blood because the claims were directed to the natural phenomenon that MPO is correlated to cardiovascular risk, and applied “conventional MPO detection methods.” In contrast, in Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175 (1981), the Supreme Court upheld claims directed to a process for molding rubber that involved using a computer to calculate the required cooling time based on a formula called the Arrhenius equation. The Supreme Court later explained in Mayo that while the Arrhenius equation itself was not patentable, the claimed process was patentable “because of the way the additional steps of the process integrated the equation into the process as a whole.”

Exergen v. Kaz

At issue in Exergen were claims directed to methods and apparatuses for detecting core body temperature by detecting the temperature of the forehead directly above the superficial temporal artery. A temperature sensor is scanned across the side of the forehead while electronics in the detector search for the peak reading indicating the temporal artery. The core body temperature is calculated from that peak temperature based on a mathematical formula. According to the district court (No. 13-10628, D.Mass.), the parties, in post-trial briefing focused on whether Exergen’s claims, “when stripped of those elements that simply reflect law of nature, were ‘well-understood, routine, conventional activity previously engaged in …’ and whether singly or in combination, they truly illuminate an ‘inventive concept’” (quoting Mayo). It went on, however, to state that “[t]he relevant laws of nature … do not drop out of the analysis altogether.” The district court held that while the claims rely on natural laws—e.g., the formula calculating core body temperature based on temporal artery temperature—using the scanning technology in this context was sufficiently inventive and unconventional to make the claims patent-eligible.

The Federal Circuit affirmed, in a split decision. The majority held that the district court did not clearly err in finding that it was unconventional to use temperature scanning technology to measure arterial temperature beneath the skin. Though that technology was conventional in other contexts—for instance, detecting “hot spots” that could identify injuries—it was not conventionally used to measure core body temperature. The fact that such use may have been disclosed in the art was not alone sufficient to make it conventional or routine. The majority analogized this case to Diehr, explaining that the inventors had spent “years and millions of dollars” to determine the “coefficient representing the relationship between temporal-arterial temperature and core body temperature” and had “incorporated that discovery into an unconventional method of temperature measurement.”

Judge Hughes dissented, arguing that the majority erred by relying on the natural law in determining inventiveness at step two. The district court had not disputed that the relevant scanning technology was conventional in other contexts, and had found only that it was not “routinely or conventionally used for the purpose of calculating core body temperature.” Judge Hughes faulted the majority for finding inventiveness by combining conventional technology from another context with a natural law or phenomenon—he reasoned the majority’s reasoning conflicted with Ariosa, which invalidated patent claims relating to the use of conventional DNA isolation techniques in the new context of isolating certain fetal DNA.

Can Courts Consider The Natural Laws In Deciding Step 2?

One of the more interesting issues raised by Exergen is whether claims can be “inventive” under step two by combining conventional technology from another context with a newly-discovered natural phenomenon (and, if so, when). Judge Hughes is undoubtedly right that it cannot always be inventive to use conventional technology in a new context with a newly-discovered natural phenomenon. Often the only reason the conventional technology had not been applied in that new context is because no one knew the natural phenomenon—in such a case, there is nothing inventive beyond the natural phenomenon itself. For instance, in Ariosa it was not conventional to use DNA isolation to isolate fetal DNA from maternal blood serum, but only because people did not know such DNA was in the serum.

Judge Hughes seems to suggest that the correct step-two inquiry should be whether, assuming the natural phenomenon were known, it would have been conventional to combine that phenomenon with existing technology to practice the asserted claims. He argues that consideration of whether the claims are really directed to the natural phenomenon or something more specific belongs at step one, and that step two is about whether the additional limitations are independently inventive. But even aside from Exergen, the Federal Circuit arguably has not always followed that approach. For instance in Rapid Litigation Management Ltd. v. CellzDirect, Inc., 827 F.3d 1042 (Fed. Cir. 2016), the court upheld claims directed to a process of repeating the conventional steps of freezing and thawing liver cells because a skilled artisan would not have known the cells would survive multiple freeze-thaw cycles (a natural phenomenon). Though Judge Hughes characterized CellzDirect as a step-one case, the decision also held that the claims were inventive under step two.

What could be driving cases like CellzDirect and Exergen is the court’s sense that the additional claim limitations sufficiently narrow the claims to avoid monopolizing the natural phenomenon itself; courts seem to uphold claims when they incorporate natural laws into specific devices, but not when they simply tell a practitioner to apply a natural law. But, as Judge Hughes argues, this inquiry seems more appropriate at step one, as it has little to do with the search for “inventiveness” in the additional claim limitations that is supposed to drive the step-two inquiry.

Given the uncertainty in this area, patentees with potential § 101 issues should emphasize both the novelty and specificity of all claim limitations that go beyond natural phenomena themselves.

Known Does Not Mean Well-Known

Another issue relates to the majority’s statement that “something is not well-understood, routine, and conventional [in step two of the Mayo test] merely because it is disclosed in a prior art reference.” The Federal Circuit first drew this distinction (at least explicitly) just a month earlier in Berkheimer v. HP Inc., No. 2017-1437 (Feb. 8, 2018). The Federal Circuit went further in Exergen by providing an example: a thesis written in German, and located in a Germany university library, is prior art, but the thesis would not establish that something that is well-understood or conventional.

But is the distinction consistent with § 101 precedent? To start, it is not inconsistent with the various Federal Circuit decisions that found patent claims invalid without considering whether the claimed methodology/techniques were routine, conventional, or well-understood. It is also not inconsistent with Mayo and Ariosa. In Mayo, for example, the Supreme Court found that the claimed measuring step was “routinely” performed by scientists, and in Ariosa, the Federal Circuit noted patentee admissions in the specification and prosecution history referring to certain claimed techniques as “standard,” “well-known,” and “routine.” It is less clear whether the distinction was understood in Cleveland Clinic. There, the Federal Circuit referred to the claimed methods as “conventional,” but that appears to be based on admissions in the specification that the methods were “standard” and “known in the art” and that kits were “commercially available.” Under Exergen, would that be enough? If not, is Exergen at odds with Cleveland Clinic? Such questions may be addressed in the future, whether en banc, at the Supreme Court, or in future appeals of other § 101 determinations.

And what is the difference between a technique that is merely “known” (e.g., a technique disclosed in that German thesis) and a technique that is well-known and conventional? Must that technique be cited ten or twenty times in the prior art? To what extent does it have to be practiced or commercialized? If a distinction must be made, determining whether a known technique is well-known may require very specific factfindings, as the majority in Exergen noted. (Recently, the Federal Circuit was asked to consider en banc in Berkheimer whether factual issues are possible in the Section 101 analysis, and a petition for certiorari raising similar questions is pending in Cleveland Clinic.) In view of Berkheimer and Exergen, patentees may be safe admitting that aspects of their claimed invention were known, as long as they explain why those aspects were nevertheless not conventional. Still, the safer bet is for patentees to do what they can to distinguish their inventions from the prior art.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

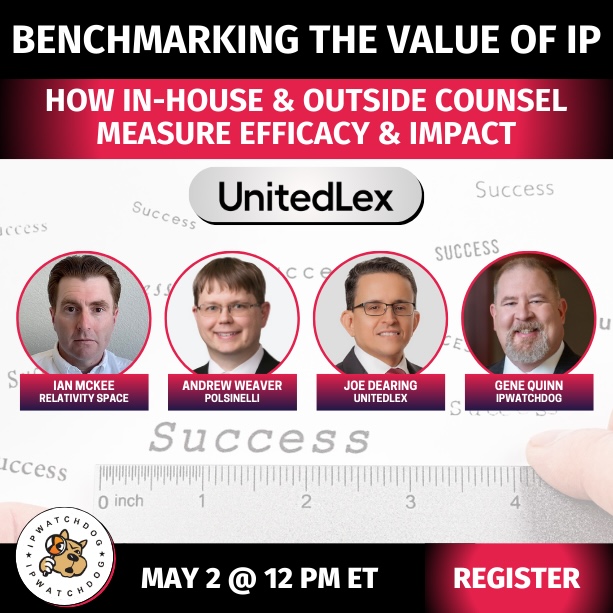

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Quartz-IP-May-9-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

2 comments so far.

Anon

April 11, 2018 11:21 am…and then along comes the Prost-led decision (thankfully non-precedential) of Maxon v. Funai, butchering the distinction as to what the “ordered combination” analysis pertains to….

Anon

April 9, 2018 09:21 amI think that the article misses a critical distinction: not only IS there a difference between known and well known (however that difference is to be eventually distinguished), the more critical element is just whose responsibility it is to MAKE that distinction.

So while the concluding remarks are geared to what applicants can (or should) do, that jump to provide advice to the applicants overshoots the plain fact that it is the Office that needs to establish – with facts and evidence – just why they believe that something is more than merely possibly known – and transcends to the higher level of being well known and conventional.

One way of looking at what well known and conventional means, then, can be to consider that something well known and conventional is also something widely practiced.

Of course, there is an important additional step that the Office must also provide: the facts/evidence that the ordered combination is what rises to the level (and not just each of the claim elements individually).

One other comment vis a vis: “But is the distinction consistent with § 101 precedent? To start, it is not inconsistent…”

I find this “to start” to be too cute. The plain answer to the question posed is “Yes, the distinction is consistent.”

If the authors (or any other readers) think otherwise, please provide a case on point. Cleveland Clinic is not such a case – it is not on point, and the attempt to “infer” something from a case that is not on point is – at best – clouding the point.