Patent claims can recite a numerical range and a patent can be awarded based on the novelty and nonobviousness of the claimed range. Normally, compositions are claimed in this manner but other types of inventions can be defined in terms of a numerical range such as a length as well. In re: Brandt (Fed. Cir. March 27, 2018) explains that very small differences in the respective ranges can support an obviousness rejection unless the inventor shows a meaningful difference exists.

Patent claims can recite a numerical range and a patent can be awarded based on the novelty and nonobviousness of the claimed range. Normally, compositions are claimed in this manner but other types of inventions can be defined in terms of a numerical range such as a length as well. In re: Brandt (Fed. Cir. March 27, 2018) explains that very small differences in the respective ranges can support an obviousness rejection unless the inventor shows a meaningful difference exists.

Manual of Patent Examining Procedure

MPEP 2131.03 explains how to determine when the range disclosed in the prior art anticipates or is an obvious variant of the claimed range. MPEP 2173.05(c) provides additional information on claiming a numerical range as part of the invention.

Four basic scenarios between claimed range and prior art’s disclosed range

Four scenarios may exist when a patent claim recites a range. For example, the claimed numerical range can be broader than the prior art’s disclosed range. (e.g., claimed range is 2.5-6, whereas prior art’s disclosed range is 4-5). The prior art’s disclosed range anticipates the claimed range of the invention. The claimed range is not novel. See MPEP 2131.03(I).

Second, the claimed numerical range can overlap the prior art’s disclosed range. (e.g., claimed range is 2.5-6, whereas prior art’s disclosed range is 5-6). Third, the claimed numerical range can be narrower than the prior art’s disclosed range. (e.g., claimed range is 4-5, whereas prior art’s disclosed range is 2.5-6). The prior art’s disclosed range may anticipate the claimed range. During examination of a patent application, examiners require an inventor to show why the claimed range is critical or any difference across the range. See MPEP 2131.03(II). Otherwise, the claim will be rejected.

Fourth, the claimed numerical range can be close to but does not overlap or touch the prior art’s disclosed range. In this instance, the prior art’s disclosed range does not anticipate the claimed range. In re: Brandt explains this relationship between the respective ranges further. This scenario is treated in a similar manner that the second and third scenarios are treated. The bottom line is that the inventor has the burden to present arguments or evidence that show that the respective ranges have a meaningful difference. Otherwise, the claimed range will be obvious.

In re: Brandt

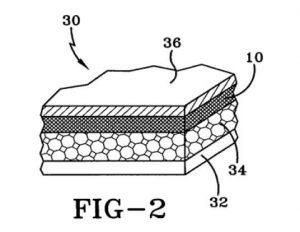

This case is an appeal from a final rejection during examination. The inventors appealed the examiner’s final rejection to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (Board). Now, the inventors appeal the Board’s findings to the Federal Circuit. The patent application at issue (US Ser. No. 13/652858) in the case relates to a roof covering. The covered roof consists of stratified layers including a roof deck 32, an insulation board 34, and a high-density overboard 10. See image below.

The claims of the patent application required the coverboard to have a density > 2.5 lbs/ft.3 and < 6 lbs/ft3. The examiner cited a prior art reference that disclosed a layer having a density between 6 lbs/ft3 and 25 lbs/ft3. The upper end of the claimed range abutted the lower end of the range of the cited prior art. This difference was described as “virtually negligible” “could not be smaller” “minor” “so mathematically close.” Because of this, the examiner rejected the patent claims as being obvious.

The claims of the patent application required the coverboard to have a density > 2.5 lbs/ft.3 and < 6 lbs/ft3. The examiner cited a prior art reference that disclosed a layer having a density between 6 lbs/ft3 and 25 lbs/ft3. The upper end of the claimed range abutted the lower end of the range of the cited prior art. This difference was described as “virtually negligible” “could not be smaller” “minor” “so mathematically close.” Because of this, the examiner rejected the patent claims as being obvious.

The inventors had two arguments in support of this appeal. First, the Board erred in finding a prima facie case of obviousness because the respective ranges did not facially overlap. In support of this proposition, the inventors cited a nonprecedential decision, specifically, In re Patel, 556 F. App’x 1005 (Fed. Cir. 2014). The Federal Circuit disagreed with the inventors’ reading of the case. Moreover, the Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s decision because the claimed range and the prior art range abut one another and the inventors did not provide any meaningful distinction between the respective ranges.

Second, the inventors argued that the Board erred in finding the prior art does not teach away from the claimed invention. During the appeal to the Board, the Board required the inventors to show the criticality of the difference between a coverboard having a density of 5.99 lbs/ft3 and 6.00 lbs/ft3. The inventors argued that requiring the inventors to make such a showing was in error. The Federal Circuit disagreed because the inventors’ arguments were tantamount to “an assertion that there is some criticality to having a coverboard density of greater than 6 pounds per cubic foot.” The Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s decision.

Ramifications for preparing a patent application

Some inventions are conducive for claiming ranges. As stated above, composition claims are stated as a range. However, even mechanical invention can be claimed as a range. For example, a lever system can be described in terms of a range even though claiming a lever in terms of a specific range would be quite limiting.

Preparing a well-crafted patent application requires a significant amount of foresight. It is not possible to foresee all of the many different challenges the patent application will encounter during examination and attacks during litigation but the goal is to anticipate and mitigate those challenges and attacks.

With this in mind, when the invention can be described in terms of ranges even for mechanical inventions, take a few minutes and think through the ramifications of changing dimensions to see if those ranges make the invention behave differently and include those insights into the patent application. The patent application can describe the ranges as narrowing or shifting brackets. More importantly, to the extent possible, the patent application should also explain how the invention behaves differently within the sub ranges. During the examination stage, the broad range may have to be narrowed to avoid the prior art range or the prior art range might be close to the claimed range. Having the reasons for differences in the subranges may help in support of the future nonobviousness arguments.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Quartz-IP-May-9-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

3 comments so far.

Anon

April 16, 2018 08:47 pmMichael,

Why do you think that there should be a difference between “predictable” and “unpredictable”…?

Patent law itself makes no such distinction.

Michael

April 16, 2018 03:15 pmA problem with this case is that the invention relates to the predictable mechanical arts, whereas the most significant use of ranges are in the unpredictable chemical arts. The holding makes sense in the mechanical arts, but the case will be cited by many patent examiners in the chemical arts to support rejections where the holding doesn’t make sense.

Anon

April 15, 2018 12:17 pmNice article on some “nuts and bolts” of patent law,

One aspect not touched here (perhaps on purpose, in order to keep the focus of the article simple) is that any time a range is used, one is engaging in a patent aspect called “climbing the ladder of abstraction.”

I point this out because “abstract” has become a “dirty word” – a bit of patent profanity, and it may be about time that we start taking that word back – start deflating the “boogeyman” that THAT word has become.

Whenever something is captured in a claim that is more than a SINGLE “objective physical structure” what we have done is recognize that the invention has more than a pin-point scope.

There is absolutely nothing wrong with claims to inventions having more than a pin-point scope.

Quite in fact, one may realize that the protection afforded in patents with claims WITH a pin-point scope is almost too minimal to have any worth (due to the fact that so often any such claim with a pin-point scope can be “designed around” with ridiculous ease and can be done so with what otherwise would be merely some “obvious” variant.

The mashing of the nose of wax of 101 (by the Court) so often overlaps with 103.

I like to point out that the Supreme Court themselves (albeit perhaps inadvertently) created (or perhaps more accurately, reinforced) this type of “protection” in the otherwise “detested” KSR decision. I always like to point out that the Court’s decisions are often double-edged swords.

In KSR, the leading edge of the sword (in the more typical “anti-patent” thrust) was that findings of obviousness would be easier – so as to prevent new inventions from overcoming the legal requirement of not being obvious. The trailing edge of that sword though is that inventions already patented were desired to be more protected (look again at Kennedy’s actual words (emphasis added):

“Granting patent protection to advances that would occur in the ordinary course without real innovation retards progress and may, in the case of patents combining previously known elements, deprive prior inventions of their value or utility.”

I would put this question up for consideration: how can prior inventions be deprived of their value or utility is NOT that prior inventions are strengthened in the “penumbra” of what those inventions cover?

This notion of “penumbra” then speaks to a stronger protection of existing patents – stronger in particular in the notion that any such “pin-point” scope that can be easily worked around is something that the patent laws should not tolerate.

For the strength of patents (and NOT necessarily for the strength in DENYING patents).

I fully admit that perhaps the Justices were not quite aware of the double edge effect that their words carried – but that double edged effect exists nonetheless.