The best practice is not only to file what is necessary, but to also file drawings that go beyond what is minimally necessary. Drawings can be your best friend.

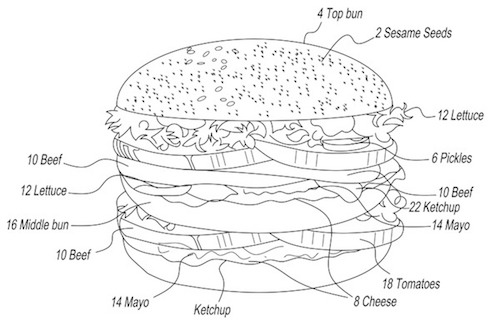

Sample patent illustration created by Autrige Dennis of ASCADEX Patent Illustrating.

For applications filed on or after December 18, 2013, other than design applications[1], U.S. patent laws no longer require that an application contain a drawing to be entitled to a filing date. See 35 U.S.C. 111. Having said that, it is an extraordinary mistake for anyone to believe that drawings are no longer required, or that submitting drawings at the time of filing is not the absolute best practice. Furthermore, it should be understood that high quality drawings — and many of them — are the single best and most economical way to expand the scope of any disclosure filed. And I say that without any drawing ability myself and without any intent for anyone to hire me to illustrate anything! My drawing skills are really quite terrible.

Inventors and those new to the profession, therefore, must understand that drawings should be viewed as required, period.

35 U.S.C. 113 continues to require one or more drawings if necessary for the understanding of the subject matter. And therein lies the first problem. Yes, it is technically possible since passage of the Patent Law Implementation Treaty Act in December of 2013 to obtain a filing date without a drawing, but if you are going to need to file a drawing to satisfy 35 U.S.C. 113, how are you going to be able to do that without adding new matter?

For those new to patents, new matter is absolutely prohibited from being added to a patent application. When you file a patent application you are defining your invention and being awarded a filing date for that invention, which is defined by everything present at the time of filing, whether in text, claims or drawings. If you try and add description or drawings later that will add matter not present at the time of filing you are trying to sneak so-called new matter into the application, which is prohibited. The only way to add that new matter is to file another application and get a new filing date, but that requires separate filing fees, which can and will get expensive. That is why the first filing needs to be as complete as you can make it; you cannot add new matter without another filing and set of filing fees.

So, if you filed an application without drawings how can you add illustrations later without them including new matter? Drawings are always going to include new matter, that is unless you file stick figures to nominally satisfy the drawing requirement, but stick figure drawings won’t really help understand the invention, and certainly don’t benefit the applicant by expanding the disclosure. Therefore, it will likely be practically impossible to submit drawings to satisfy this requirement without violating the prohibition against new matter.

Therefore, better practice remains to file applications with any and all drawings necessary to understand the invention. The best practice is not only to file what is necessary, but to also file drawings that go beyond what is minimally necessary. You never know later on during prosecution what details you may wish you had explained in the written text, what nuances you may wish you had elaborated upon. Drawings can be your best friend, and case law has shown that judges can and will look to the drawings to see what is fairly disclosed and would be understood by the person of skill in the relevant technology or scientific field. Therefore, with drawings more is better.

While the drawing standards and specific requirements are quite picky, and go well beyond the scope of this primer, and frankly beyond the knowledge of most patent professionals[2], there are a few things you should know about photographs.

While patent laws will at times allow you to file photographs in lieu of line drawings, as an amateur photographer I strongly discourage inventors from using photographs. While there are always exceptions, in my experience photographs almost never capture the invention as well as line drawings could. Given how relatively inexpensive good patent drawings can be ($75 to $125 per page, sometimes less) it makes far more sense to hire a professional and get the best patent drawings possible.

Additional Information

For more tutorial information please see Invention to Patent 101: Everything You Need to Know. For more on drawings I recommend the following reading:

- Patent Drawings 101: The way to better patent applications

- Patent Drawings and Invention Illustrations, What do you Need?

- Working with Patent Illustrations to Create a Complete Disclosure

For more information specifically on patent application drafting please see:

________________

[1] Pursuant to 35 U.S.C. 171, a design application (whether filed before, on, or after December 18, 2013) must be filed with any required drawing to receive a filing date.

[2] For the most part, the drawing requirements can be found at MPEP 608.02. Patent practitioners typically do not do patent drawings, but rather rely on the services of patent illustrators who provide specialized services.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[[Advertisement]]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Enhance-1-IPWatchdog-Ad-2499x833-1.png)

![[[Advertisement]]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Ad-1-The-Invent-Patent-System™-1.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IP-Copilot-Apr-16-2024-sidebar-700x500-scaled-1.jpeg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

2 comments so far.

Guy Letourneau

June 24, 2018 02:21 pmGene:

I believe there may be a narrow exception where the product or product by process is an anisotropic or well-blended homogenized mass. In US 4,623,551, “Cheese Foam,” the abstract provides description sufficient for the imagination. In a case like this, or a new inventive concrete aggregate mix, or a method that yields much finer or more consistent particle sizes for a pulverized material – could an illustration actually narrow the BRI of a claim by introducing visual limits on feature or particle sizes or their expected variations, such as for bubbles illustrated within the foam, or gravel sizes, or other graphical hints about the consistency of a mixyure? Or, would uniform distribution be implied as a limitation, where the invention might work just as well with less homogeneous clusters or pockets of materials or voids spaces which would also be within the written scope of the claim?

(Agent, not a lawyer, so I am wondering how this might play out.)

Paul Morgan

June 24, 2018 10:06 amGreat post, especially since some corporate clients and firms seem to be cost-limiting their application preparation to only two sheets of drawings.