As of April 2018, there were more than 114,000 people listed on the national transplant waiting list according to information published online by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. A new person is added to the waiting list every 10 seconds and an average of 20 people day every day as a result of not receiving an organ transplant. The waiting list for those who need to receive organ donations has risen steadily since 1991, when just over 23,000 Americans were waiting for a healthy organ from a donor.

At the same time, however, the American medical community has been making strides forward both in terms of the number of organs donated as well as the number of donated organs transplanted into the patients who need them. In 2015, organ transplants in the U.S. exceeded 30,000 transplants for the first time ever, a 5 percent increase over the previous year, and nearly 35,000 transplants were completed in 2017. Through the first six months of 2018, nearly 15,000 organ transplants were conducted. The overwhelming majority of organ transplant procedures completed between January 1st, 1988, and May 31st, 2018, were kidney transplants; the 433,675 kidney transplants completed during that 30-year span accounted for 58.9 percent of all completed transplants. Liver transplants came in second place behind kidneys with a total of 159,327 such transplants, or 21.6 percent of all transplants.

This July 8th marks the 32nd anniversary of the issue of a seminal patent in the field of organ donation and it protected a technology which became crucial for testing organ tissues to determine potential matches between organ donors and recipients. The lead inventor listed on this patent is Paul Terasaki, a 2018 inductee into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. Once again, we return to our Evolution of Technology series to take a look at the history of organ transplants, the technology that has been developed to improve the success of those transplants and where Terasaki’s innovation fits into that story.

The History of Organ Transplants from Skin Grafts to Kidney Replacements

Evidence of human organ transplantation actually extends back a few millenium to as early as the 2nd century B.C. when the Indian surgeon Sushruta experimented with autografted skin transplants, and there is some evidence of bone transplantation that occurred during the Middle Ages. The history of modern organ transplantation, however, extends back to 1869 when the Swiss surgeon Jacques-Louis Reverdin performed the world’s first “fresh skin” allograft by removing healthy skin from a body and seeding it in another area that needed to be covered. It would take nearly another 40 years before the next major advance in transplant surgery when the first successful full-thickness corneal transplant was completed in 1905 by Austrian-born ophthalmologist Eduard Zirm.

It would take until the middle of the 20th century for the next wave of organ transplant advances to get underway but it marked a major sea change in the ability of surgeons to successfully complete transplants. In 1954, American plastic surgeon Joseph Murray and American doctor David Hume completed the first successful kidney transplant between identical twins. The first kidney transplant between fraternal twins happened a few years later in 1959 and then the next year, the first kidney transplant between siblings was accomplished.

The decade of the 1960s saw a dramatic increase in the number of historical firsts in the realm of organ transplant procedures. The medical team of Murray and Hume also completed the first successful transplant of a kidney coming from a deceased donor in 1962. The following year would also see the first recovery of lung and liver organs from deceased donors for transplants. The first transplant of pancreatic tissues occurred in 1966, completed by University of Minnesota surgeons William Kelly and Richard Lillehei in an attempt to treat a patient with type 1 diabetes. The next year saw a relative explosion in organ transplant advances as 1967 saw the first liver transplant, the first simultaneous kidney and pancreas transplant as well as the first heart transplants, one in the U.S. and the other in South Africa.

Paul Terasaki and the Terasaki Tray Revolutionizes Donor-Recipient Matching

Despite these achievements in the realm of organ transplants, surgeons all over the world faced a tremendous issue in the risk that a recipient’s body would not accept a donor organ, leading to rejection of that organ by the body’s immune system and almost certain death. These issues are one reason why the first successful kidney transplants involved twins; the genetic similarities between the two bodies helped to ensure that the risks of organ rejection were minimal.

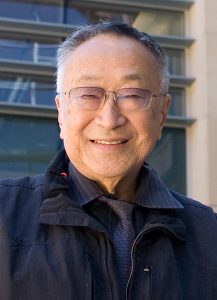

Born in September 1929 in Los Angeles, CA, Paul Terasaki would go on to pursue a career as a scientist in which he would develop the first major solution to the issue of determining a match between organ donors and recipients. His early life was difficult, having been born less than one month after the Black Tuesday stock market crash that kick-started the Great Depression. He also spent three years of high school with his family in the Gila River War Relocation Center, an internment camp for Japanese Americans living in the U.S. during World War II.

After high school, Terasaki completed all levels of higher education at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), completing his bachelor’s, master’s and Ph.D. programs in zoology. After realizing that he had developed allergic reactions to most of the animals which he worked upon as a zoologist, Terasaki decided that he would refocus his career on immunology during his post-doctoral studies in London.

Upon returning to California and UCLA after completing his studies in London, Terasaki continued his work exploring both the cellular and molecular basis for the rejection of tissues in the bodies of organ transplant recipients. This led to the development of tissue typing tests based on the recognition that human leukocyte antigen (HLA) cell markers, which are involved in the progression of autoimmune diseases, could be measured to determine potential matches between organ tissues from donors and the bodies of transplant recipients. The microcytotoxicity test developed by Terasaki was capable of performing a total of 1,000 tissue tests with the use of only one microliter of serum from human patient samples.

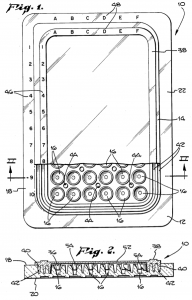

The revolutionary work of Dr. Terasaki can be seen in the technology claimed by U.S. Patent No. 4599315, titled Microdroplet Test Apparatus and issued on July 8th, 1986. Listing Terasaki as the lead inventor, it claims a microdroplet test apparatus adapted for use in determining HLA antigens by measuring lymphocyte cytotoxicity, the apparatus including a tray having a top surface, a bottom surface and a perimeter with a plurality of microtest wells in the tray for receiving and holding test solutions including lymphocytes and selected cytotoxic reagents capable of lysing selected lymphocytes. The resulting invention, which became widely known in the medical field as the “Terasaki Tray,” provided a suitable means for handling minute quantities of reagents as well as an apparatus in which numerous tests could be carried out simultaneously. This particular advance improved upon previous Terasaki Trays, which exhibited difficulties with lymphocytes either sticking or not flowing completely down the constant slope microstest well side wall, by shaping the test wells to promote localization of the lymphocytes at or near the microtest well bottom.

The revolutionary work of Dr. Terasaki can be seen in the technology claimed by U.S. Patent No. 4599315, titled Microdroplet Test Apparatus and issued on July 8th, 1986. Listing Terasaki as the lead inventor, it claims a microdroplet test apparatus adapted for use in determining HLA antigens by measuring lymphocyte cytotoxicity, the apparatus including a tray having a top surface, a bottom surface and a perimeter with a plurality of microtest wells in the tray for receiving and holding test solutions including lymphocytes and selected cytotoxic reagents capable of lysing selected lymphocytes. The resulting invention, which became widely known in the medical field as the “Terasaki Tray,” provided a suitable means for handling minute quantities of reagents as well as an apparatus in which numerous tests could be carried out simultaneously. This particular advance improved upon previous Terasaki Trays, which exhibited difficulties with lymphocytes either sticking or not flowing completely down the constant slope microstest well side wall, by shaping the test wells to promote localization of the lymphocytes at or near the microtest well bottom.

Terasaki would go on to co-found One Lambda to market the Terasaki Tray assay plate and that company was acquired in 2012 by Thermo Fisher Scientific for $925 million. After retiring in 1999, he would go on the found the Terasaki Research Institute to continue exploring solutions to problems in organ transplantation. Before he passed away in January 2016, Terasaki received a number of awards and recognitions including the 2011 UCLA Edward A. Dickson Alumnus of the Year award; the UCLA Medal in 2012; and the U.S.-Japan Council Lifetime Achievement Award in 2014.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

One comment so far.

Karol Franks

July 10, 2018 10:50 amPaul Terasaki saved so many lives through organ donation, including my daughter. He was a kind, humble man. And generous too http://newsroom.ucla.edu/releases/paul-terasaki-donates-50-million-158486