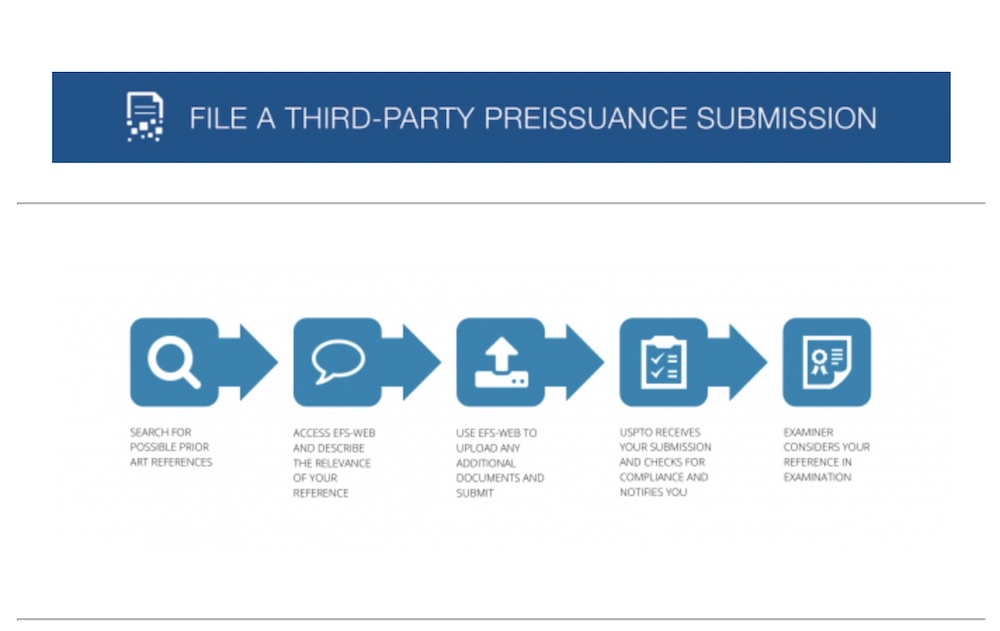

A decent patent strategy starts with protecting your current commercial product. A better patent strategy builds on this by not only considering what is, but what could be. For example, medical devices are constantly evolving, and it is prudent to protect not only the first generation of your device, but an array of possible second generation devices. Many practitioners stop at this second stage to the detriment of their clients. There is, however, a gold standard that looks beyond the task at hand and considers a client’s portfolio not in isolation, but as part of a whole. This gold standard incorporates both offensive and defensive strategies. To provide real value, consider the actions of others and invest time studying the patent landscape and gathering business intelligence from competitors’ filings. Additionally, instead of passively observing such filings, a company should also consider being more active by filing one or more third-party submissions (often termed preissuance submissions) in their competitor’s pending applications. These third-party submissions are a terrific defensive tool to slow down or impede your competitors’ patent ambitions.

In practice, here is how these submissions play out. Suppose for example that company A has been developing intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) devices for years. Company B decides that it too wants to pursue this technology, and ramps up its patent filings in that space. Because A is diligent, they monitor activity in the space, and see that a new application assigned to B has recently published. Instead of passively observing B’s efforts, A may submit prior art via third-party submissions to block B’s applications. A may want to do this for several reasons:

- A third-party submission reduces your competitor’s chance of getting a patent. In fact, there are no limits to the number of references or number of third-party submissions that can be filed in a single application with certain small exceptions. It would be extremely difficult for a patentee to overcome a mountain of relevant prior art, arranged in various combinations, carefully laid out for an Examiner by a skilled patent attorney with the resources to do so.

- Relatedly, third-party submissions often unearth the most relevant prior art. In the example above, A has been in the market for years and may be intimately knowledgeable of the prior art and the state of the art, more so than an Examiner. By using third-party submissions, A may proffer the most relevant art to the Examiner, or provide a combination of references that did not occur to the Examiner. While most Examiners are competent, it is not uncommon for an Examiner, pressed for time, to make a rejection over a combination of reference X in view of Y, when Y in view of X would be better. This is not a criticism of patent Examiners, but an acknowledgment of the (often unreasonable) time constraints imposed on them. In fact, the Supreme Court expressly recognized this problem, and cited these same limitations as a reason to uphold IPRs as constitutional in Oil States.

- Third-party submissions are cost-effective–orders of magnitude cheaper than attempting to invalidate an issued patent via IPRs, or drafting a litany of non-infringement and/or invalidity opinions. In short, each patent issued to a competitor, even if in error, comes at a cost. Third-party submissions reduce the chance of that happening.

- Third-party submissions may be filed “anonymously” (i.e., through a strawman). The submission is not completely anonymous as the filing party must be identified, but the real party in interest may remain unidentified. Our firm routinely files third-party submissions on behalf of clients who wish to preserve their anonymity. In fact, most third-party submissions are actually filed at the direction of other law firms. By distancing the third-party submission from the real party in interest, as well as their familiar outside counsel, anonymity is maintained, and retaliation from the competitor is less likely.

- Third-party submissions are not only relevant to the application in which they are filed, but they may taint other applications in the same family, or other families as well. Once submitted, the patentee must now consider this newly-cited art, and is presumed to have knowledge of it. The patentee must then decide whether to file information disclosure statements in related applications. In fact, a properly timed third-party submission in one pending application may provide sufficient reason for a patentee to withdraw from issuance another application. Thus, even if the deadline for filing a third-party submission has passed, references may be introduced via a backdoor third-party submission, by filing them in another related pending case, and putting the onus on the patentee to cross-cite the references or risk a possible claim of inequitable conduct.

There are some limitations. Practitioners should be aware, for example, that the time limits for filing a third party submission are strict, and that the strategy requires active monitoring of competitors’ filings. Submissions generally must be made before the later of six months from publication, or the date of the first Office Action on the merits. Because Office Actions can issue out of turn, and because the first action predictor is merely an estimate, it is advisable to docket the six-month date from publication for an application of interest. Additionally, third-party submissions are limited to patents, published patent applications or other printed publications. Other facts or reasons as to why your competitor’s application is defective (e.g., incorrect inventorship) may be valid, but they are generally not accepted through this channel. Moreover, an Examiner is not required to apply prior art from a third-party submission, even if the submission was deemed compliant.

Finally, while third-party submissions will not result in estoppel, there is a risk that a botched third-party submission, either by the filing party in inaccurately setting out the relevance of the documents, or by the Examiner in failing to apply the art properly or at all, will simply strengthen a patent that results. Thus, some have criticized third-party submissions and advocated “keeping the powder dry” till the very end by holding on to the best art and using it to invalidate an issued patent during litigation. While this may be appropriate for some clients, seeing a litigation to its end is too costly for many. Instead, certain clients seek a dose of clarity from the patent office at the earliest opportunity in order to make informed business decisions, and forcing a competitor to narrow their claims is often good enough.

In short, there are myriad reasons to file third-party submissions and many clever ways to use them. While such submissions have been largely ignored, there are opportunities where they provide tremendous value at minimal costs.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

6 comments so far.

Anon

July 13, 2018 10:55 amThank you Mr. Sieman.

I agree that third party submissions are not for everyone (or for every situation).

However, I will stress again that the point of reference for “keeping your powder dry” should be corrected.

I do not think that adding in the fact that certain parties for whatever reason (be that their financial capability or their aversion to risk) changes the proper point of reference. For those parties that you point out, ANY litigation whatsoever may well be problematic – but that would be an entirely different problem than the topic under discussion.

Sadly, I have encountered far too many “hopeful” innovators who simply have not planned for what may be the necessary action of enforcing a patent right (if such a right is obtained). My client counseling always includes a discussion with the client as to WHY they want to obtain a patent, and what is involved in the full cycle of such. Some may merely want a patent and have no desire to enforce that patent whatsoever (this is true of both small and large clients, by the way).

Another facet to be aware of (and to be wary of) is to conflate “cost of litigation” in and of itself with patenting. This has been a tactic of anti-patent forces who seek to diminish the power of patents because of the “boogeyman” of litigation costs being “unfairly” imposed. The answer to the problems of costly litigation should be pursued regardless of – and thus separate from – the particular “item” being litigated. Reforms then in a general litigation context then should be the driver (and not a focus on changing patent law). As it is, litigation is a designed mechanism for enforcing one’s rights, and is a necessary vehicle in order to be able to enforce those rights when recourse outside of the courts is not effective (for example, when large multinationals refuse to bargain with small innovators – and make no mistake, there IS a large and active Efficient Infringer group out there that include such large multinationals).

Peter Sleman

July 12, 2018 10:08 pmJNG, I’m following up with some interesting data from bigpatentdata on TPS, but “uptake” rate will follow if I’m able to get it:

http://blog.bigpatentdata.com/2018/07/the-high-stakes-world-of-bee-patents-charts-on-third-party-submissions/

Peter Sleman

July 12, 2018 04:24 pmAnon, your point on publication is a great one. Regarding keeping the “powder dry,” you are certainly correct that ideally, you would be able to stop a suit in its tracks at a very early stage. But attorney fees can rack up quite fast, even in the early stages of litigation, and for some risk-averse or bootstrapped clients, even the early stages of litigation are unaffordable. Third-party submissions are one strategy, and they’re not for everyone.

JNG, I’ve had mixed results and I will pass along quantitive data if I find it. You are correct in that your mileage may vary, and I think it will also vary by technology sector. Some Examiners are more astute than others. From my experience, detailed claims charts seem to help. If an Examiner has been selected for an application, I would also suggest taking a look at Examiner Ninja before filing a third-party submission to glean some insight on how they operate.

JNG

July 12, 2018 01:14 pmPeter

I’d be curious to know your “uptake” rate by the Examiners on these submissions. I’ve done over 50 of them now, and the breakdown is pretty disappointing. In more than half of the cases, the Examiner doesn’t even bother looking at the submission; I mean, it isnt even mentioned at the end of the Office Action as a related art citation. For an example, see SN 14/583,311 where I cited some cases in July 2016 in a 3P submission (mapping the claims against a reference) against a FB pending application that matches social network users based on some affinity scores. Months later, in the first OA, the Examiner acts as though there is nothing there.

In half of the other half of the cases, the reference is mentioned but not applied in any fashion. Its just acknowledged, but nothing more. Of the remaining 25%, the disposition is again mixed: about half the time the Examiner will distinguish it on his/her own without any input from the applicant. It is in ~15% of the total cases where the Examiner actually applies the reference in the manner cited in the submission. For an example of that, see SN 14/275444 which is a case to Google that the Examiner used my reference in the Feb 2016 Office Action.

Overall, I’ve found the exercise to be extremely inefficient for the same reasons I think we find historic weaknesses in the PTO: many Examiners are somewhat close-minded and unwilling to accept that someone else could know or search the field of art better than they can. Thus, they reject the input out of hand. Now, granted, I may be simply a crappy 3P submission drafter, but I would have expected the Examiners to at least take note of the references out of caution. I also did not file the submissions in the form of complete ghost-written Office Actions, where I laid out the analysis word-for-word so that they simply could put their signature on the page (i.e., REALLY appeal to their lazy side) and that probably count against me. But to do that would require a pretty significant investment so the client would really need to find that case important.

Anon

July 12, 2018 08:28 amAlso, there is a bit of a misunderstanding in the “keeping your powder dry” section of the article.

The author references a high cost of seeing litigation through to the end as a reason NOT to keep your powder dry (as related to the possibility that putting the references in front of the USPTO may not have the desired impact).

But that is not the correct comparison point.

Rather, the point of keeping your powder dry is to be able to share that powder at the beginning stages of any litigation/enforcement action. As the author notes, counsel outside of the Office may provide a much more impactful and cogent invalidity position than an examiner. Sharing this (at the different timing of a potential start of a litigation) – only with the patent holder – may have multiple benefits.

First, of course, is that this may stop the suit against you. Well before the article’s “through to the end” comparison point.

Relatedly (but different), this also may NOT stop suits against OTHER competitors.

Having someone else having a patent then becomes a strength for you as that other person’s (still deemed valid) patent clears away other would be competitors (who may not be as sophisticated as you and your own patent landscaping efforts).

There are a few other items in the article that I find disagreeable (including the notion of “sneaking around” timing rules, and trying to “trap” applicants on cross-citing), but standard IDS practice (cross-cite EVERYTHING) and the fact that Examiners more often than not prefer their own searches anyway, make those items more of a nit.

Anon

July 12, 2018 08:12 amOne of the reasons that I will typically advocate to my clients to have a universal “no-publication first” policy is based on the tactics shared in this article.

There are limits to the request for non-publication, of course. But having a universal policy wherein the choice of non-publication is the default and then changing that status (which one has generous opportunities to do) only in those situations (and at such later dates) as necessary prevents tipping off competitors who may want to play the games as discussed by the author.