For people starting out in the patent field, virtually all job announcements require some patent prosecution experience. A typical requirement is, for example, at least 2 years of experience in prosecution. I get it. What employer wants to invest in training only to see a person slip away once they can finally do something useful. Rather, you’d like to on-board the person, get them working immediately and discover what gaps may exist from their past experience and work to fill them in. Great idea, except it is hard to pull off, especially with 1500 or so newbies entering the patent professional ranks each year.

For people starting out in the patent field, virtually all job announcements require some patent prosecution experience. A typical requirement is, for example, at least 2 years of experience in prosecution. I get it. What employer wants to invest in training only to see a person slip away once they can finally do something useful. Rather, you’d like to on-board the person, get them working immediately and discover what gaps may exist from their past experience and work to fill them in. Great idea, except it is hard to pull off, especially with 1500 or so newbies entering the patent professional ranks each year.

Another issue is “mentoring”. Always promised and (almost) never delivered. The new generation of patent professionals seems to me to want more and regular feedback as to how they’re doing and encouragement as to next steps. All good in theory – but one size does not fit all, and time is always at a premium during the work day. After hours interaction is also hard to come by owing to the long days already recorded and the need for some work place/home place separation. So how do you handle the foregoing issues as an employer and/or how can you get a jump on these issues as a potential employee? Training? Internships?

Internships are a good idea if you have the time and inclination, and even better if, while in school, they can translate into credits toward a degree. While you might not be learning and doing the nitty gritty it takes to do the job you hope to have, you’ll at least be exposed to many of the issues typically encountered and learn from watching those responsible. A great opportunity for those who are either “patent curious” or “patent serious” is the externship program run each summer at the USPTO. My son did this externship as a Junior/Senior year transition as an aerospace engineering undergrad. He interned in the Design area, and then went back and became an Examiner in the utility area. He is now in law school and looks forward to joining the ranks of us in the near future. But, family aside, I recommend this to many prospective patent people as I speak at law schools across the country. The patent business is terrific, in my view, but not necessarily for everyone. This is especially true of being a USPTO Examiner. It is a job unlike any other. Hence, witnessing aspects of it first-hand provides a much better basis to make decisions going forward and gauging whether interest can likely become vocation.

Clerking of any sort at any patent related enterprise, public or private, is also an excellent first step for the same reasons as the USPTO externship mentioned above. Clerking introduces you to the vocabulary and process of law in context. You get to know, again, what is going on and even if you are not drafting work product, you interact and support those who are. And if, by the end, you do get to write a portion of a brief, decision, amendment, or application, so much the better.

All the foregoing works if you are proximate any of these opportunities. And, even if you can avail yourself of these things, they still do not equate to 2 years of experience. So, how about some training or classes or books. Sadly, most training you’d find helpful exists, if at all, internally, at most enterprises, and available CLE is either too specific, i.e., a single case study, or too generic and high level and geared to those with the experience already extant. Classes would be good, if available. But, in my experience the patent realm is a mile wide, i.e., there are a few of us spread all over, but only an inch deep. Hence, only a few loci exist where “classes” would make sense. Books are good, and PLI, where I have taught for 20+ years has a terrific IP library with many titles that should be at your elbow as they are at mine. Seriously, if your firm does not have a copy of every PLI IP title in their library, go talk to whomever is in charge of such things and “make it so!”

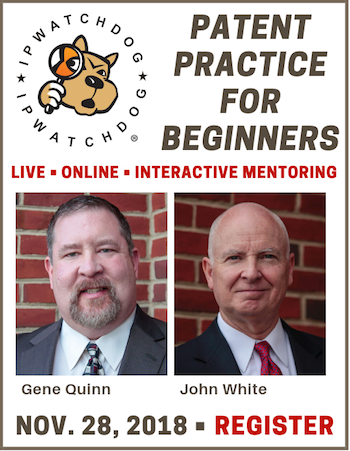

Gene Quinn and I have talked about this need gap as we have traveled and taught across the US for these past 18 years, and have long talked about a course to fill that gap for people getting started; and, also alleviate the concern for those hiring such newbies that they cannot “hit the ground running”. Our suggested solution is a 21 hour course that we call Patent Practice Training for Beginners. The course is delivered in 3 hours increments over six days during a two week period. All of the lectures are delivered “live” on the web — nothing is pre-recorded. Each day also includes a mentoring/question segment at the end of each session, which runs at least 30 minutes but frequently goes longer so every question gets answered. To a student they have all found these mentoring sessions extremely helpful, and although optional attendance has been 100%.

Gene Quinn and I have talked about this need gap as we have traveled and taught across the US for these past 18 years, and have long talked about a course to fill that gap for people getting started; and, also alleviate the concern for those hiring such newbies that they cannot “hit the ground running”. Our suggested solution is a 21 hour course that we call Patent Practice Training for Beginners. The course is delivered in 3 hours increments over six days during a two week period. All of the lectures are delivered “live” on the web — nothing is pre-recorded. Each day also includes a mentoring/question segment at the end of each session, which runs at least 30 minutes but frequently goes longer so every question gets answered. To a student they have all found these mentoring sessions extremely helpful, and although optional attendance has been 100%.

We’ve given the course, by now, a handful of times and received good feedback. It is sort of the Goldilocks solution: not too long or short, covers every USPTO issue, and provides examples and a review of every paper that can be filed. Students also get a significant discount on the two best PLI titles to get you started in prosecution.

In my estimation, this course solves two issues. One, the experience gap, which likely brings a confidence gap, and the mentoring gap. We provide web access to monthly mentoring sessions for the year after the course. When I left the USPTO as a former examiner in January 1987 and headed for Cushman, Darby and Cushman, the prior USPTO experience provided a huge confidence boost. Even if I had never written first hand, an amendment or application, I had seen many and had been on the other side of the prosecution equation. As for mentoring, there was none. But fellow Associates filled the gap (sort of – after hours – at the Hay Penny Lion pub downstairs), and whatever partner you did do work for, if you did well, would keep giving you work and, if you did poorly, or required too much feedback, …. the work stopped. Ah, good old sink or swim. So, if you swam well enough, often enough, you got a raise and were kept. If not…… But that was so 30 years ago, this is now.

It seems to me a firm would welcome the chance to buy neutral training that boosts experience and knowledge and doesn’t cut into the work day and eliminates their need to organize and staff and provide the same internally. If a person leaves at the end of two years, they are out some training costs, but have had productive work in the meantime.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

9 comments so far.

Anon

October 25, 2018 11:26 am“Also, it was a matter of pride to write patents that could never be rendered invalid.”

Scrivening by the Court has rendered patent profanity beyond measure.

This is a systemic problem – one that yields a solution along the lines of Congress waking up (if that were possible), applying their power of jurisdiction stripping against the Supreme Court to yank their fingers out of the nose of wax, reset a properly functioning Article III court of review (the CAFC is beyond tainted), and once again strive to make having a patent a noble venture.

CP in DC

October 25, 2018 09:34 amNight Writer

I think the problem is that people are often hired now to see how much they can be exploited and employees know this and as such will jump ship for a better opportunity.

I agree. With the commoditization of patent prosecution, the profession has turned into a business about the bottom line. I often hear how patent prosecutors are fungible goods easily replaced. The refrain “anyone can do patent prosecution” is so often repeated, that people forget that not anyone can do it well. Something often forgotten.

So if firms invest little in prosecutors, pay them poorly, and make people feel like they can be replaced at the drop of a hat, why would anyone expect them to stay? Worse, why would anyone or any firm expect people to enter the profession (if we can still call it that).

The demise of the large IP boutiques has taken its toll on training. I started at a top IP boutique and learned the trade by others willing to give their time. Not everyone trained, but enough did. Also, it was a matter of pride to write patents that could never be rendered invalid. That no longer exists with many practitioners. Now it’s meet the budget, put out the product, and move on.

Night Writer

October 24, 2018 12:54 pm@4 CP

I don’t know. I guess for me it wasn’t hard. I was hired by one of the top IP boutiques and they didn’t mind training me. They had training programs, notebooks, and mentors. Also they didn’t dump all the hard work on you. Now I am at a large IP boutique (not as prestigious) and we don’t train people.

I think the problem is that people are often hired now to see how much they can be exploited and employees know this and as such will jump ship for a better opportunity.

In my first law firm they said their goal was to keep me there for the rest of my life and they meant it. I had to leave for another city for personal reasons.

Josh

October 24, 2018 11:48 amAnother great way to get some experience and show employers that you are patent serious can be found at the University of Minnesota. They offer a Master’s of Science in Patent Law. The program sits you down next to second and third year law students to learn the basics of patent law. As part of the program, students also get the chance to work with several practicing patent prosecutors to get some hands on experience responding to office actions, claim drafting, and even entire patents. I did this program myself, and now I am a practicing patent agent only four months after graduating! If you are patent serious this is a great option

CP in DC

October 23, 2018 10:28 amNot to be overly pessimistic, and alternative is a 2 year internship for new lawyers. Ok, now the problems. If a lawyer can go into another field without the loss of income, they will. Howrey (remember them) offered something similar for all their lawyers. The program offered training and no pressure of meeting billable hours for less pay…. they got no takers.

Canada has a 2 year apprenticeship for new lawyers. The problem: because all lawyers must do it, they are viewed as cheap labor (and paid accordingly) to do the mundane tasks no one wants.

Obviously any program would have to include patent agents, otherwise people would opt for that route and avoid two years of lower pay.

It’s a tough problem and I’m glad we are talking about the necessary training to become a good prosecutor. Simply passing the patent bar is not enough.

CP in DC

October 23, 2018 10:17 amI think no one trains anymore. Working for a mill or the PTO will teach you fast and cheap work, not the skill sets you want to sell to any mid-level boutique, much less BigLaw. A mill is a mill for a reason, fast and cheap work, hardly the training ground for the complexities of drafting and legal reasoning necessary for complex arguments. On this site we bemoan the low quality examination at the PTO with the common conclusory rejections (obvious to combine or try) or factless 101 arguments (think Berkheimer memo). Also, the PTO now compartmentalizes prosecution, examiners don’t know how to fix claims, modify priority claims, describe figures, or many other needed skills to prosecute an application. Granted working at the PTO punches your ticket to move on, the mill not so much (we all know the type of work at the mills).

The time to train is not in the budget. We spoke about tighter budgets and that eats into time spent training. Experienced prosecutors want to get their time and move on. No one wants to spend precious time on non-billable training. Few do it for the greater good.

The basic problem is that everyone wants trained people (get a job after 2-3 years) and no one wants to train. This problem was around 20 years ago and is still around today (just more pronounced). It’s simple, it takes time and effort (and money) to train and trained people leave as soon as they can for the better paying job (who wouldn’t). So the cycle continues.

If you want change then change the dynamics. I don’t know how, because I no longer care to train. I did my time and firms did not reward the work, so I stopped. Can the PTO or mills fill the vacuum? Probably not for the reasons I discussed. Perhaps clients’ demand for better work will motivate to train (I know of clients that don’t allow first and second year associates to work on their matters), but right now budgets are all that matters.

abitofftopicbut

October 22, 2018 11:42 pmJohn at 2:

I highly recommend the prosecution mill route. You will learn actual prosecution. I’ve known too many people that started at the patent office and were tainted with the Office’s perspective for many years after they left – it can be hard to unteach many of the bad habits and misinterpretations of law that examiners learn.

Also, somewhat unrelated – Biglaw is no place for patent prosecution, not for anyone. Clients are getting ripped off (because the attorneys have much less time, and the work is often given to people who need hours, not ones who are qualified), and prosecutors are being overworked and underappreciated. I was drawn into biglaw by the fabled “prestige.” I saw that client budget caps were 20% or more higher. Then I saw that my bill rate was 60% higher than it was at the boutique I started at. And my expected hours were higher. And I got a, wait for it, 6% pay bump. I was pretty good and still billed a good 7 or 8 hours a day at biglaw, with almost 100% realization/efficiency. But that was still nowhere near enough. I got calls every month saying that I couldn’t put my status as “heavy” when I was billing fewer than 180 hours a month. And even though I was collecting 1700-1800 hours a year, all they cared was that I wasn’t billing 2200+. Sure, the one or two partners in the patent group appreciated my work, one even offered me $20k straight up to stay when I said I was leaving. But nothing would have been worth it to stay in biglaw trying to do patent prosecution. Anecdotal, but in my view patent prosecution should be done in smaller groups where appropriate focus and attention can be given to the work without all the pressures of money and prestige found in biglaw.

John

October 22, 2018 07:02 pmI think the two best routes are to either work for a patent mill or for the USPTO. A mill will have higher pay and easier transition to more fulfilling jobs after two years experience, whereas the USPTO has better job security, quality of life, and a more gradual ramp-up process.

Either way you’re on a fast track to the mythical 10,000 hours it takes to master a skill.

The course discussed in the article probably would help some people get a shot from a decent mid-sized boutique. I doubt it would move the needle for BigLaw IP departments, which are still beholden to law school tiers and Latin honors for applicants with little experience.

Michael J. Feigin, Esq. http://PatentLawNY.com

October 22, 2018 11:12 amSo true … it’s a very hard field to break into. There’s a tremendous learning curve and not much training. My prior employers received training and years of employment from places like RCA and AT&T. That was back in the 1980s and earlier. By the 2000s I had to beg and work as a secretary to get experience starting out and got a lot of ‘no’ before finding places to even get that far. I had to teach myself a method of dealing with Office Actions with my own acronym …

LOCA –

Limitation – what is the phrase in the claim?

Office Action – what does the Office Action state about this particular limitation?

Citation – what does the citation actually say?

Analysis – what’s the truth?

On the flip side, at a small law firm I don’t have the time to really train people … I’ve taught people the above a bunch of times with the result being either a) they sink or b) they go somewhere else bigger and better after they’ve learned.

Great idea to try and fill the gap … I might be sending potential interns to you first to see how serious they are. I took a PLI course way back when … passed on the first try. (Also had to take the exam the day after the course ended thanks to the OED unexpectedly granting my application to take the exam right after I sent the request … giving me a 90 day window to take it which ended right after my law school semester / the day after the PLI course. Good times.)