While there is still work to be done, the Music Modernization Act does solve some long-standing issues in the music industry.

What do California, Florida, and New York have in common in addition to coastlines? These three states were the sites of recent disputes between Flo & Eddie, the owner of pre-1972 musical recordings, and Sirius XM, who publicly performed those recordings, regarding whether common law or statutory copyrights existed in those states and if so, what level of compensation was due for the public performance. When Congress permitted sound recordings to be copyrighted over four decades ago, it didn’t extend that coverage to pre-1972 recordings. Pandora and Spotify were also sued for unpaid royalties.

What do California, Florida, and New York have in common in addition to coastlines? These three states were the sites of recent disputes between Flo & Eddie, the owner of pre-1972 musical recordings, and Sirius XM, who publicly performed those recordings, regarding whether common law or statutory copyrights existed in those states and if so, what level of compensation was due for the public performance. When Congress permitted sound recordings to be copyrighted over four decades ago, it didn’t extend that coverage to pre-1972 recordings. Pandora and Spotify were also sued for unpaid royalties.

This issue, and the piecemeal nature of licensing for digital music on a per-work, per song basis, were part of the impetus for the stakeholders in the music industry to work together to create the Music Modernization Act, signed into law on October 11, 2018.

Flo & Eddie vs. Sirius XM: California: not “Just Another Town”

Why is this case so significant? Because Flo & Eddie were successful enough to get a multi-million dollar settlement.

The backdrop: in 2015, Sirius XM had already settled with some of the major music labels for $210 million dollars. In 2016, Spotify had agreed to pay the National Music Publishers Association $30 million dollars.

While Flo & Eddie lost in Florida and New York because no common law copyright rights existed, the duo won in California since the court held that Cal. Civ. Code § 980(a)(2) protects pre-1972 sound recordings. The District Court granted Flo & Eddie’s motion for summary judgment, and Sirius XM was held to be liable for unauthorized public performance for broadcasting and streaming pre-1972 sound recordings as well as for conversion and misappropriation. Factual disputes prevented summary judgment against Sirius XM for reproducing the sound recordings in operating its satellite and internet businesses.

Flo & Eddie were also successful in certifying the class, defined as “the owners of sound recordings fixed prior to February 15, 1972 (“pre–1972 recordings”) which have been reproduced, performed, distributed, or otherwise exploited by Defendant Sirius XM in California without a license or authorization to do so during the period from August 21, 2009 to the present.” These circumstances set the stage for settlement, where class counsel received 30% of the total settlement amount in attorney’s fees, Flo & Eddie received $25,000 each, and the class was guaranteed $25.5 million recovery for past damages, a potential additional $10 million pending the outcome of the California Supreme Court’s decision, and a prospective royalty rate of 3.5% in exchange for Sirius’s 10–year license to perform the pre–1972 recordings.

Sirius XM isn’t alone in acceding to multi-million dollar settlements. The May 2018 settlement in the Spotify class action case resulted in $43 million dollars for past mechanical royalties for songwriters and publishers and perhaps $63 million dollars for future payments. Spotify was pursued for its alleged decision to systemically avoid paying mechanical royalties to songwriters and publishers.

Is the Flo & Eddie saga over? Not quite yet: the following question was certified to the California Supreme Court in Flo & Eddie vs. Pandora: (1) Under section 980(a)(2) of the California Civil Code, do copyright owners of pre-1972 sound recordings that were sold to the public before 1982 possess an exclusive right of public performance? (2) If not, does California’s common law of property or tort otherwise grant copyright owners of pre-1972 sound recordings an exclusive right of public performance?

The Pandora case was fully briefed before the Music Modernization Act was enacted on October 11, 2018, and to date, the docket does not reveal any new filings or action by the California Supreme Court.

The Wixen Lawsuit

Wixen, established in 1978, is a copyright management and royalty compliance company, representing many artists, including Tom Petty, the Doors, and Janis Joplin. It’s no secret that the Music Modernization Act, even in draft form, was and is a compromise bill: it eliminates certain remedies, such as statutory damages and attorneys’ fees, against streaming services such as Spotify unless a lawsuit was filed before January 1, 2018. So on December 29, 2017, Wixen sued Spotify for streaming thousands of songs without paying mechanical royalties to songwriters and publishers. Wixen wants Spotify to pay $1.6 billion dollars. Of the streaming services, when Spotify does pay, its reimbursement is one of the lowest in the industry in comparison to Tidal and Apple. The litigation is ongoing.

Federal protection for pre-1972 recordings

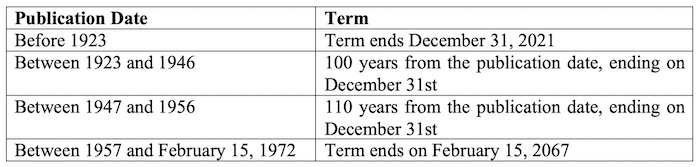

As part of the compromise among music industry stakeholders, the Music Modernization Act adds pre-1972 sound recordings, including a public performance right, to the Copyright Act. An extra term of protection is added to the standard 95 years from the first publication date:

Fair Market Value Approach

The Music Modernization Act also makes several significant changes to how the people who create music — songwriters, vocalists, and instrumentalists — are compensated, and for the first time in US copyright law, the work of producers and engineers is specifically recognized. SoundExchange, which manages the payment of digital streaming royalties for post-1972 works, is tasked with payments to all stakeholders for the now-covered pre-1972 works. This is a much needed revenue stream for producers and engineers whose older sound recordings were used for many years on a royalty-free basis. In a stark change from prior practice, royalty rates will be negotiated using the fair market value concept of the “willing buyer, willing seller;” the goal is to increase compensation to the music creators when digital platforms (who had earned millions from streaming) use their music.

This fair market value approach will also be utilized in setting royalty rates for works in the databases of performance rights organizations ASCAP and BMI, and instead of one Southern District of New York judge assigned to all of these cases, the assignment will be random.

Public Database of Music

Significantly, the Music Modernization Act creates a new Mechanical Licensing Collective, funded by the digital services, to issue blanket mechanical rights licenses to the digital services and collect and distribute royalties to songwriters and publishers. This comprehensive public database should be a boon to the music industry. The new collective is tasked with identifying rights holders and creating a public database of musical works and sound recordings so that attribution information — matching songwriters and publishers to songs — can be corrected and timely payments made. The prior cumbersome notification process, where the user had to send notification requests to the last known address of the musical copyright owners, will be replaced entirely after a transition period. The next step is for the US Copyright Office to issue the underlying regulations for the 17-member MLC Board, which will include music publishers (10 voting members), songwriters with publishing rights (4 voting members), and 1 non-voting member from each of these groups: a non-profit advocating for songwriters, a non-profit trade association of music publishers, and a digital licensee coordinator (3 members).

Open Issues

Not all issues in the music industry were solved by the Music Modernization Act: licensing of physical sound recordings (vinyl and CDs) will still occur on a per-work, per song basis. Terrestrial radio pays songwriters and publishers royalties for playing music, but it doesn’t pay performance or sound-recording royalties. And while the goal of one public database is laudable, the responsibility still lies with songwriters and publishers to submit copyright applications and to submit all of their musical works and sound recordings to the MLC. While copyright owners may, at their own expense, use an auditor to review the royalty payments once a year, if there is an underpayment, the MLC will pay that amount but not the cost of the audit. Additionally, the 10 music publishers on the MLC Board outvote the independent songwriters. While there is still work to be done, the Music Modernization Act does solve some long-standing issues in the music industry.

Image Source: Deposit Photos.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

3 comments so far.

Gordon Daniel

February 2, 2019 06:29 pmThe text of the “Music Modernization Act” is available online. Large business in the music business have been screwing songwriters since the days of Stephan Foster. The MMA does not change that. It simply perpetuates the same old problems. “Fair Market Value” by the way is what a willing seller will sell and what a willing buyer will pay. It is not a committee deciding how much the seller should be paid. That is communism.

Amy B Goldsmith

November 11, 2018 07:57 pmDear BP:

You’re quite welcome.

Kind regards,

Amy

BP

November 11, 2018 02:12 pmThanks to you and IPWatchdog for this informative post!