“There is a misconception—a myth, really—that the innovation or idea behind the technology becomes more valuable once it has been declared to be standard essential. Such an understanding fundamentally misunderstands the role of Standard Development Organizations and the purpose of Standard Essential Patents.”

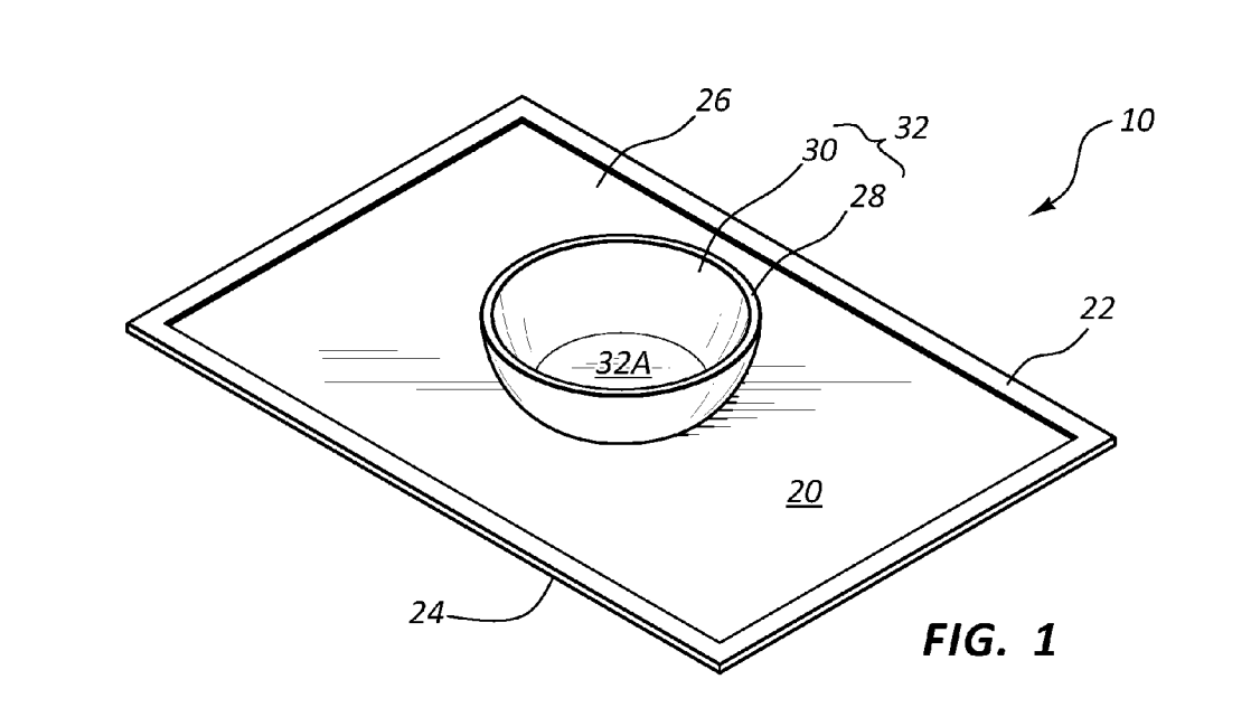

Standard Essential Patents (SEPs) are patents that are unavoidable for the implementation of a standardized technology. They represent core, pioneering innovation that entire industries will build upon. These patents protect innovation that has taken extraordinary effort to achieve.

Standard Essential Patents (SEPs) are patents that are unavoidable for the implementation of a standardized technology. They represent core, pioneering innovation that entire industries will build upon. These patents protect innovation that has taken extraordinary effort to achieve.

Standard Development Organizations (SDOs) exist as a mechanism for industry innovators to work together to collectively identify and select the best and most promising innovations that will become the foundation for the entire industry to build upon for years to come. Those contributing patented technologies to the development of a standard are asked to provide a FRAND (which stands for Fair, Reasonable and Non-Discriminatory) assurance, in essence committing to providing access to patents that are or may become essential to the implementation of the standard.

The Myths

There is a misconception—a myth, really—that the innovation or idea behind the technology becomes more valuable once it has been declared to be standard essential. Such an understanding fundamentally misunderstands the role of SDOs and the purpose of SEPs. “The opposite is quite true,” explained Matteo Sabattini, Director of IP Policy for Ericsson. “A technology makes it into a standard because it is valuable to solve a specific problem.”

The concepts behind the industry cooperation and the FRAND framework for pioneering innovations seem easy and straightforward. Nothing could be further from the truth. Some economic realities never change. Those who create the technology want to be paid (or paid more) and those who use the technology don’t want to pay (or pay less). And this leads to yet another popular misconception about SEPs.

Some erroneously believe that technology implementers are locked into a standard, and that patent owners seek to extract unjustified licensing payments after implementers have spent great sums of money investing in the implementation of the standard. “Again, the opposite is true,” Sabattini explained. “Implementers that refuse to take a license, or hard-ball patent owners, are trying to reduce their costs and the return to standards developers when those developers have already sunk their R&D investments.”

Innovators Versus Implementers

Sabattini is exactly correct, but this is a point often lost on the public. Take for example the next great communication platform—5G technology. If you watch TV, or live in a major city with mega-billboards, or read practically any major publication, you will undoubtedly see advertisements from technology implementers touting their investment in rolling out 5G technologies to users. While it is important not to minimize the contribution of those technology implementers across the final mile to consumers, it is the likes of Ericsson and Qualcomm that have paved the way for the innovation of 5G technology from the ground up. So, while consumers wouldn’t get connected to 5G platforms without the technology implementers, 5G technology wouldn’t exist for technology implementers to roll out in the first place if not for Ericsson and Qualcomm.

It is the technology innovators that have invested massive sums of sunk costs innovating the technologies that the industry, by and through SDOs, adopts as the standard that technology implementers can build upon. It is this adoption that allows different technology implementers to roll out and create uniform, cross-platform consumer products and services, all built upon the significant investment of the technology innovators.

SEPs at the ITC

In recent years, we have seen a proliferation of disputes that are at their core about SEPs and the innovations they cover. They range from cross-border patent litigations and a race to a friendly courthouse to technology users suggesting antitrust authorities around the world institute investigations into licensing practices relating to SEPs.

Even as these disputes have grown in number, and the Courts, tribunals and forums asked to weigh in continue to grow in number, oddly enough, the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) has not yet really faced a situation where they have been asked to decide critical questions dealing with SEPs. So far, according to Ted Essex, retired Administrative Law Judge for the ITC and current Senior Counsel at Hogan Lovells, there have been 12 cases dealing with what could potentially be considered SEPs at the ITC. In one of those cases, the parties stipulated to the existence of SEPs. In the other 11 cases, neither party presented evidence on the issue. Judge Essex believes this may be because the defendants do not want to concede the issue of validity by presenting evidence that the patent is standard essential. While accused infringers will not present evidence on essentiality, because they would like to continue to challenge validity at the ITC and in other forums, patent owners likely also do not present evidence that the patent at issue reads on the standard, so they do not have to admit facts that would lock them into a FRAND license.

The issue of SEPs, SDOs, cross-border patent litigation and antitrust implications will only become a bigger, more complicated one for technology implementers and technology innovators alike.

Hear from the Experts

Join me on Thursday, February 7, 2019, for a wide-ranging discussion on the issue of Standard Essential Patents, Standard Development Organizations, Fair Reasonable and Non-Discriminatory licensing requirements and related antitrust investigations. Joining me will be Theodore Essex, retired Administrative Law Judge for the ITC and current Senior Counsel at Hogan Lovells, and Matteo Sabittini, Director of IP Policy for Ericsson.

Image Source Deposit Photos

Image ID: 135238328

Copyright: tumsasedgars

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IP-Copilot-Apr-16-2024-sidebar-700x500-scaled-1.jpeg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

6 comments so far.

Ron Hilton

February 6, 2019 01:27 pmRon Katznelson @4, My only point was that not all SEPs are the products of formal efforts by SDOs. Your rebuttal applies to all SEPs, not just my comment. But if the rationale behind SEPs is valid, then my comment is consistent with that rationale. I fully agree that a patent portfolio does not necessarily confer market monopoly power. In most cases it does not. But in some cases it does. For example, if the patent protects an interface specification that has evolved into a defacto industry standard, no would-be competitor can design to that interface without infringement, and customers have no real choice since it is a prevalent industry standard for an entire product ecosystem. That is the definition of a “SEP” if you believe that they exist. But you certainly have the right to argue that they don’t really exist – that there is always a feasible alternative to or circumvention around any standard. But in my experience, that is not really the case, and patent and anti-trust law sometimes do come into conflict.

Jim

February 6, 2019 12:16 pm>> But that is precisely the intended result of our patent system. … Ironically, Mr. Hilton’s notion would have us believe that the law of innovation works against itself.

Actually, the intended result is the public good, and I’m not sure Mr Katznelson is the best judge to say this is identical with “a right to exclude a competitor’s products” in ALL cases. The law is a practical thing, and patent law isn’t some original constitution.

It’s as if some don’t accept the distinction between patents and SEP patents, such are the absolute statements made. FRAND is ill-defined we all know, but Mr Katznelson would have us believe it means absolutely nothing.

SEP and FRAND are things that will need greater definition going forward in the modern world, and there have been many suggestion on how to make the process better. The sky isn’t falling.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24119893

Ron Katznelson

February 5, 2019 07:05 pmI am always amazed by statements such as that of Ron Hilton @2 — “patent portfolios that effectively confer monopoly market power;” and “customers are the losers in this situation, continuing to pay higher prices for dated technology.”

Really? customers are losers? Who forces them to use inventive technologies that are still under the patent term? They are winners — not losers — because they must be deriving benefits that would not have been available but for the invention. As Judge Giles Rich said, “A time-limited exclusive right to subject matter which was neither known, nor obvious from what was known, takes nothing from the public which it had before.” If consumers do not want to “lose,” let them use the prior art or wait until the patent term expires.

The right to exclude under a patent, 35 U.S.C. § 154, is by definition a right to exclude a competitor’s products, which, by definition permits the patent holder to charge higher prices to compensate for R&D expenses and investment risks that others have not made nor taken; such exclusion necessarily affects consumer choice.

But that is precisely the intended result of our patent system. Mr. Hilton’s notion that “Innovations in the form of improvements … can be blocked from reaching the market by the incumbent’s refusal to cross-license” is a familiar refrain. It ignores, however, the much larger (average) economic magnitude and scale of non-obvious and disruptive inventions compared to follow-on “improvements.”

Ironically, Mr. Hilton’s notion would have us believe that the law of innovation works against itself.

Jacek

February 5, 2019 01:53 pmSince many of us (Inventors) actually believe in death of patents in US when we take in consideration actions of PTAB, Supreme Court and total ignorance of the real Issue by Congress from the infringer point of view Isn’t easier just invalidate the Patent and be done with the issue. Aren’t we all acting under false pretenses that in era of ” efficient infringement” patent means anything in US

Ron Hilton

February 5, 2019 01:49 pmNot all SEPs are the product of SDOs. There are defacto industry standards that arise over time, with large patent portfolios that effectively confer monopoly market power on the industry incumbent. Innovations in the form of improvements upon the defacto standard can be blocked from reaching the market by the incumbent’s refusal to cross-license. That is because they stand to lose more by the loss of monopoly power than they would gain from the improved technology. The customers are the losers in this situation, continuing to pay higher prices for dated technology.

Josh Malone

February 4, 2019 08:01 pmI think that there is yet another layer. Real innovators would deliver 20Gbps without hazardous millimeter wave transmitters. But without a functioning patent system the plan is to cram multiple high frequency transmitters onto every city block and incessantly bombard the inhabitants with these potential harmful waves. This is Russian and Chinese style “innovation”.