“At what point does patent law protect the discovery or creation of plants or animals that contain elements that exist in nature in some form, are created using natural processes and human intervention, or a combination of the above?”

Much has been written about the uncertainty in U.S. patent law concerning laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas following the Supreme Court’s decisions in Mayo v. Prometheus and Alice Corp Pty Ltd v. CLS Bank Int’l. A recent decision from the Enlarged Board of Appeal at the European Patent Office (the Enlarged Board), however, demonstrates that the United States is not alone in grappling with issues surrounding patent eligibility.

Much has been written about the uncertainty in U.S. patent law concerning laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas following the Supreme Court’s decisions in Mayo v. Prometheus and Alice Corp Pty Ltd v. CLS Bank Int’l. A recent decision from the Enlarged Board of Appeal at the European Patent Office (the Enlarged Board), however, demonstrates that the United States is not alone in grappling with issues surrounding patent eligibility.

In the case of genetically modified plants and animals, questions arise on where to draw the line between human invention and biological processes. Earlier this year, the Enlarged Board reversed a 2015 decision that had held that product-by-process patents could be sought for genetically modified plants and animals despite a patent exclusion for “essentially biological processes.” The 2015 decision was not without controversy, and five years later the Enlarged Board agreed to revisit the issue. In its latest decision, the Enlarged Board changed course and concluded that the “essentially biological processes” exclusion applies both to processes and also the products—i.e., the animals or plants—created from those processes going forward.

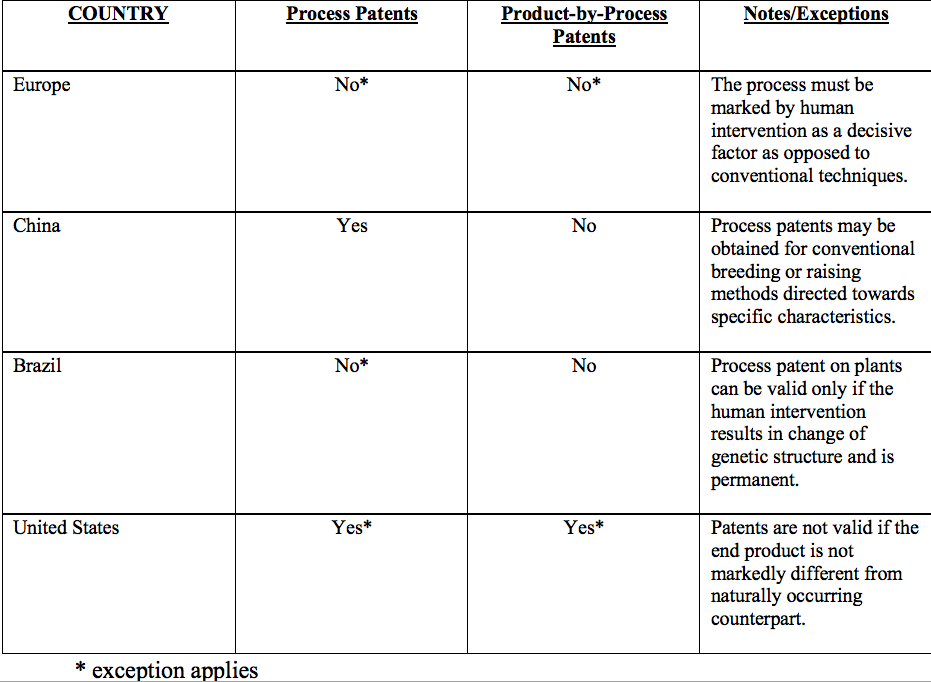

Across the globe, the patentability afforded certain plants and animals is under heavy scrutiny as countries consider what it means to discover or create a living thing. At what point does patent law protect the discovery or creation of plants or animals that contain elements that exist in nature in some form, are created using natural processes and human intervention, or a combination of the above? For example, a tomato with reduced water content, broccoli with a selective increase in anticarcinogenic glucosinolates, or an animal that is bred with the assistance of genetic markers to produce certain traits. The answers to these questions are not easy and are jurisdiction specific. To provide guidance, this article offers a brief review of the scope of patent protection for animals and plants in the United States, Brazil, Europe, and China.

Recent Developments

On May 14, 2020, the Enlarged Board issued a lengthy ruling regarding the interplay between Article 53(b) of the European Patent Convention and Implementing Regulations Rule 28(2). At issue, was whether Article 53(b)’s bar on “essentially biological processes” also included products derived from these processes.

The cases dealt with two patents, one on tomatoes and the other on broccoli. The tomato patent was directed toward a method for breeding tomatoes having reduced water content; a tomato capable “of natural dehydration while on a tomato plant” “unaccompanied by microbial spoilage” despite being on the vine past the point of ripening. The patent included claims that covered the products (tomatoes) made by that process. Similarly, the broccoli patent concerned broccoli that contained a selective increase of anticariogenic glucosinate. The methods claimed in both patents included “backcrossing,” selective breeding, screening and identifying certain traits, and propagation.

In its 2015 decision, the Board held that, while method claims were invalid under Article 53(b)’s exclusion for claims directed toward essentially biological processes, product-by-process claims were valid, in decisions now referred to as Tomato II and Broccoli II.

Following the 2015 decisions, and in response to criticism by various coalitions, the European Patent Office amended the Implementing Regulations and added Rule 28(2) to explicitly exclude products “exclusively obtained by means of an essentially biological process.” Quickly becoming a hot topic of public debate, the newly amended rule was referred back to the Board for a determination as to its validity in light of the Board’s previous decision interpreting Article 53(b). Over 40 written statements were submitted by amici on the question, including from public and government institutions (e.g., Austrian Patent Office, the Danish Government), the EU Commission, plant breeders’ associations (e.g., German Plant Breeders’ Association, Euroseeds), non-governmental organization (e.g., No patents on seeds!), and legal experts.

In a surprise decision, the Enlarged Board determined that Rule 28(2) was not invalid for extending the exclusionary scope of Article 53(b) to include the products of essentially biological processes, in its opinion G 3/19. The Enlarged Board held that patent protection could not be granted to “product claims or product-by-process claims directed to plants, plant material or animals, if the claimed product is exclusively obtained by means of an essentially biological process or if the claimed process feature define an essentially biological process.” Interestingly, the Enlarged Board noted that “[a] particular interpretation which has been given to a legal provision can never be taken as carved in stone, because the meaning of the provision may change or evolve over time.” With this note, the Enlarged Board appeared to acknowledge the fluidity of the legal issues presented and left open the possibility for future evolution of the law on this issue.

State of the Law

Europe

In Europe, patents are generally governed by the European Patent Convention. Article 53 of the European Patent Convention states the various exclusions to patentability. As relevant here, Article 53 precludes patent protection for “plant or animal varieties or essentially biological processes for the production of plants or animals.” As detailed above, the European Patent Office expounded upon Article 53(b) in Rule 28(2), which extended the exclusion to “plants and animals exclusively obtained by means of an essentially biological process are excluded from patentability.”

The touchstone for patent protection is whether a proposed claim contains an “essentially biological process” or not, which is (perhaps unsurprisingly) unsettled. In 2010, when first considering the tomato and broccoli patents, the Enlarged Board held that a process is not “essentially biological” if it contains a step that introduces or modifies a trait in the genome, “so that the introduction or modification of that trait is not the result of the mixing of the genes of the plants chosen for sexual crossing.” (G 0001/08, G 0002/07). The Guidelines for Examination in the European Patent Office (“EPO Guidelines”) further clarifies the phrase “essentially biological”: “A process for the production of plants or animals which is based on the sexual crossing of whole genomes and on the subsequent selection of plants or animals.” (EPO Guidelines Part G, 5.4.2). The EPO Guidelines also instruct that the Article 53(b) analysis applies to the patent as a whole to determine whether it is “essentially biological” and any technical steps of human intervention are ignored. Under the EPO Guidelines, a patent may not be granted if it includes any instances of crossing, inter-breeding, selectively breeding, or selfing. (EPO Guidelines Part G, 5.4, 5.4.2). Finally, the EPO Guidelines permit the examiner to read into the patent application an essential biological process even if one is not mentioned. An important exception to note is that a patent can relate to conventional breeding practices if it is directed towards a plant or animal that is naturally unable to reproduce.

China

Under China’s Patent Law, Article 25, patents are not allowed for “scientific discoveries” or “animal or plant varieties.” In the Guidelines for Patent Examination (“PRC Guidelines”), these terms are defined very broadly. Animal is defined as a “life form which cannot synthesize carbohydrate and protein by itself but maintains its life only by absorbing natural carbohydrate and protein,” excluding humans. (PRC Guidelines, Section 4.4). Similarly, the term plant “refers to the life form which maintains its life by synthesizing carbohydrate and protein from the inorganics, such as water, carbon dioxide, and inorganic salt, through photosynthesis, and usually is immovable.”

Two important exceptions apply to these broad exclusions. First, the exclusions do not apply to the non-reproductive components of a plant or animal that have been modified or any by-products from an animal or plant. Accordingly, a patent can be sought for most physical or physiological modifications of animals or plants. Second, similar to Europe, China allows patents on processes for the creation of animals or plants, if they are not “essentially biological.”

To determine whether a process is “essentially biological,” the examiner is instructed to look at the extent of human involvement or intervention. “If the human technical involvement is the controlling or decisive factor for achieving the result or effect of that process, the process is not essentially biological.” (PRC Guidelines, Section 4.4). Accordingly, a patent may be granted for the process of raising animals bearing certain characteristics such as increased/reduced fat content or higher yield. Similarly, a process patent for the cultivation of plants through irradiation or certain soil treatments are valid as would certain instances of cross-breeding, if one or more of the steps involved significant intervention, i.e., forced fruiting of an asexual plant.

Brazil

In Brazil, Industrial Property Law No. 9.279, governs patent rights. Under Article 10, patents may not be granted for “all or part of natural living beings and biological materials found in nature, or isolated therefrom, including the genome or germ plasm of any natural living being and the natural biological processes.” Similar to China, this is a broad exclusionary definition that prohibits patenting of “natural living beings.” Unlike China however, the guidelines do not provide any exceptions to this broad exclusion. Instead, Article 10’s exclusion is expanded to cover “all or part of living beings,” whether natural or genetically modified. The only narrow exception provided is for “transgenic microorganisms that satisfy the three requirements of patentability—novelty, inventive step and industrial application . . . [and] express, by means of direct human intervention in their genetic composition, a characteristic normally not attainable by the species under natural conditions.”

A patent may be sought on the process of cultivating plants under certain criteria. In 2015, the National Institute of Industrial Property issued a resolution clarifying that patents for production processes could be granted for modified plants or animals obtained by means other than a “natural biological process.” (Resolution Nº144/2015 (noting that patents involving animals are subject to the restriction that if the claims “cause suffering thereto without resulting in any substantial medical benefit to human beings or animals from such processes,” they are not patentable)). This resolution defined “natural biological process” as a process that does not include human intervention or “technical means.” Similar to Europe, the resolution notes that if the process at issue occurs in nature, without any human intervention, then a patent cannot be granted. Accordingly, if a patent is directed towards producing a plant through genetic modification it may be denied if the mutation is reproduceable in nature, even if only under certain rare circumstances. The resolution concludes that “biological processes are considered nonnatural when human intervention is direct in the genetic composition and are permanent in character.”

United States

In the United States, three forms of protection exist for plant development: Utility Patents, Plant Patents, and Plant Variety Protection Certificates. While overlap certainly exists between these three systems, generally a utility patent offers the broadest scope of protection when available. Under 35 USC § 101, a patent may be obtained for certain plants and animals and the processes directed towards their production. See Ex Parte Hibberd, 227 USPQ 44e (PTO Bd. Pat. App. & Inter. 1985); Ex parte Allen, 2 USPQ2d 1425 (Bd. Pat. App. & Inter. 1987); J.E.M. Ag Supply, Inc. v. Pioneer Hi-Bred Int’ l, Inc., 534 U.S. 124, 143-46, 122 S.Ct. 593, 605-06, (2001) (noting that 35 U.S.C. § 101 coexists with the Plant Patent Act and the Plant Variety Protection Act due to the differing requirements and protections of each). And in Ass’n for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc., 569 U.S. 576, 133 S. Ct. 2107 (2013), the Supreme Court laid out the framework to apply when a claim is directed towards a “product of nature,” such as a plant or animal. The Court determined that the central question for patent eligibility is whether the product “was new with markedly different characteristics from any found in nature.” Id. at 577.

To assist examiners in determining whether a patent is directed toward a “product of nature,” and therefore ineligible, the United States Patent Office published guidance on how to apply the markedly different analysis. In a slight variation of the human intervention test, as applied in Europe, the PTO’s analysis focuses on comparing the proposed patented subject matter to its “naturally occurring counterpart in its natural state.” The examiner is instructed to look at various characteristics of the products such as structure and function. This open-ended analysis is designed to be applied on a case-by-case basis, which introduces a lot of uncertainty into whether a patent may be granted or not. Similar to Brazil, a proposed patent’s subject matter or end result is not markedly different from “an inherent or innate characteristic of the naturally occurring counterpart or an incidental change in a characteristic of the naturally occurring counterpart.”

Conclusion: Evolution is Natural

As shown above, the there is little global agreement about the proper scope of patent protection for developing plants and animals. In terms of permissiveness, China’s approach to patentability offers the widest breadth of protection. Generally, China’s system allows for patents on methods of productions as long as a human is involved in some capacity. While this permissive approach is attractive, it is not without some drawbacks as a developer should consider the patent’s strength and scope as it relates to long-term patenting costs. In contrast, Brazil has the most restrictive approach to the patentability of plants and animals, effectively limiting patent protection to only production processes for genetically modified plants that have no naturally occurring counterpart.

As between the United States and European Union a comparative analysis is more nuanced due to inherently different tests: markedly different (in the United States) and essentially biological (in Europe). Under the U.S.’s markedly different test a patent may issue for an animal or plant that is created through conventional means, such as selective breeding, as long as the end-product contains a characteristic distinct from any naturally occurring comparator. On the other hand, one can theorize a patent that entails a non-essentially biological process, such as genetic mutation, radiation, CRISPR, to consistently produce a naturally occurring mutated product. The former may be valid in the United States but not the European Union, and the later vice-versa.

As this discussion continues across the globe, further conversations are expected to be held concerning how we determine whether a certain breeding technique is “conventional” and whether someday genetic modification will be included in that grouping as its use continues to grow. As noted by the Enlarged Board, the rules governing this space “can never be taken as carved in stone” because as countries continue to grapple with these issues, the law likewise will evolve; it’s only natural.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Copyright: elenathewise

Image ID: 6696935

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

No comments yet.