“It is clear from a review of the different company patent portfolios that it will be difficult to obtain patent claims to cultured/substitute meat products per se. The inclusion of a new or different ingredient, like Impossible Foods’ plant-derived heme, makes product patent claims easier to obtain.”

Meat substitute technologies and the growing industry based on those technologies have seen significant growth in recent years, from the number of startup companies to the amount of investment money to the industry.

Meat substitute technologies and the growing industry based on those technologies have seen significant growth in recent years, from the number of startup companies to the amount of investment money to the industry.

This article analyzes the patent protection being sought and obtained by the various companies active in this young industry, taking a “deep dive” into the company patent portfolios with a detailed look into the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) files of the identified patent applications to understand some of the patent prosecution strategies, successes and problems encountered as the companies seek to protect their technology and investments.

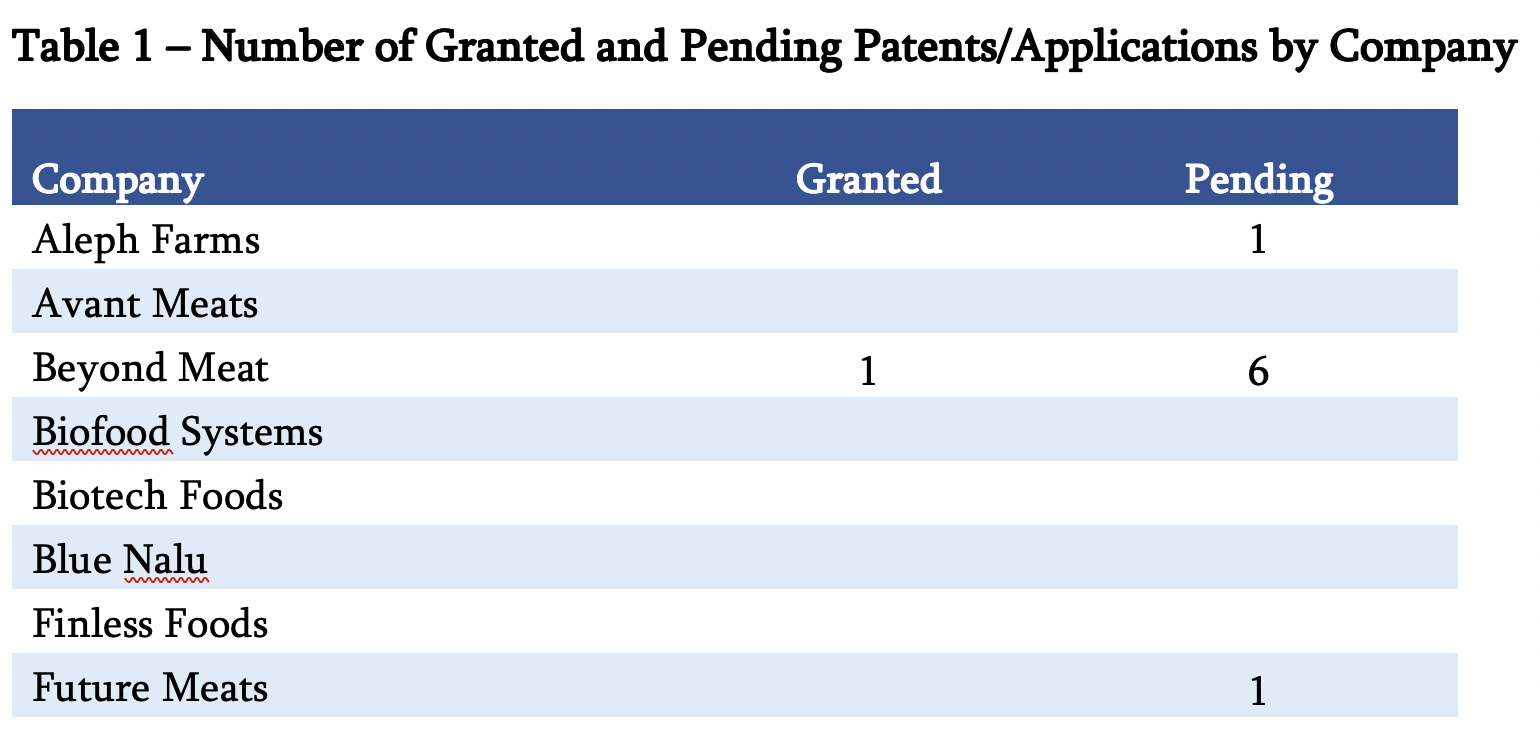

Table 1 lists all of the companies analyzed for this report, and identifies the number of granted patents and published pending patent applications in each company patent portfolio:

Details of any company patent portfolio from only public data can be difficult, since the publicly available information may not include IP that has been licensed by a company. In addition, patent applications typically publish 18 months after the earliest filing date, and that time lag can, for a time, obscure pending IP, especially for young startup companies.

But even accounting for those caveats, it is clear that Impossible Foods is far and away the most aggressive in developing a patent portfolio. That aggressiveness can be seen by the way numerous patents and/or pending applications have spawned from a single original application, creating mini “patent thickets” around a basic core technology. For example, Impossible Foods’ patent U.S. 9,700,067 granted from a U.S. application based on a Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) application originally filed in 2014; and the family stemming from that PCT application includes at least five other granted patents and four other pending applications. Similarly, Impossible Foods’ U.S. application 13/941,211 filed in 2013 has to date formed the basis for 10 granted patents and seven pending applications.

Many startups lack the finances to support such an aggressive patent portfolio development. But Impossible Foods has obviously made the decision to invest significant resources towards developing a sizable patent portfolio.

Understanding a company patent portfolio requires analyzing both quantity and quality. But, as military commentators often say, “quantity has a quality all its own”.

Development of a substitute meat product can involve a variety of technological aspects and innovations, including:

- The final, commercialized substitute meat product.

- Processes for making the product or making intermediate products.

- Intermediate products or materials utilized in the process to make the product.

- Additional ingredients added to the commercial product.

- Machinery utilized to make the product.

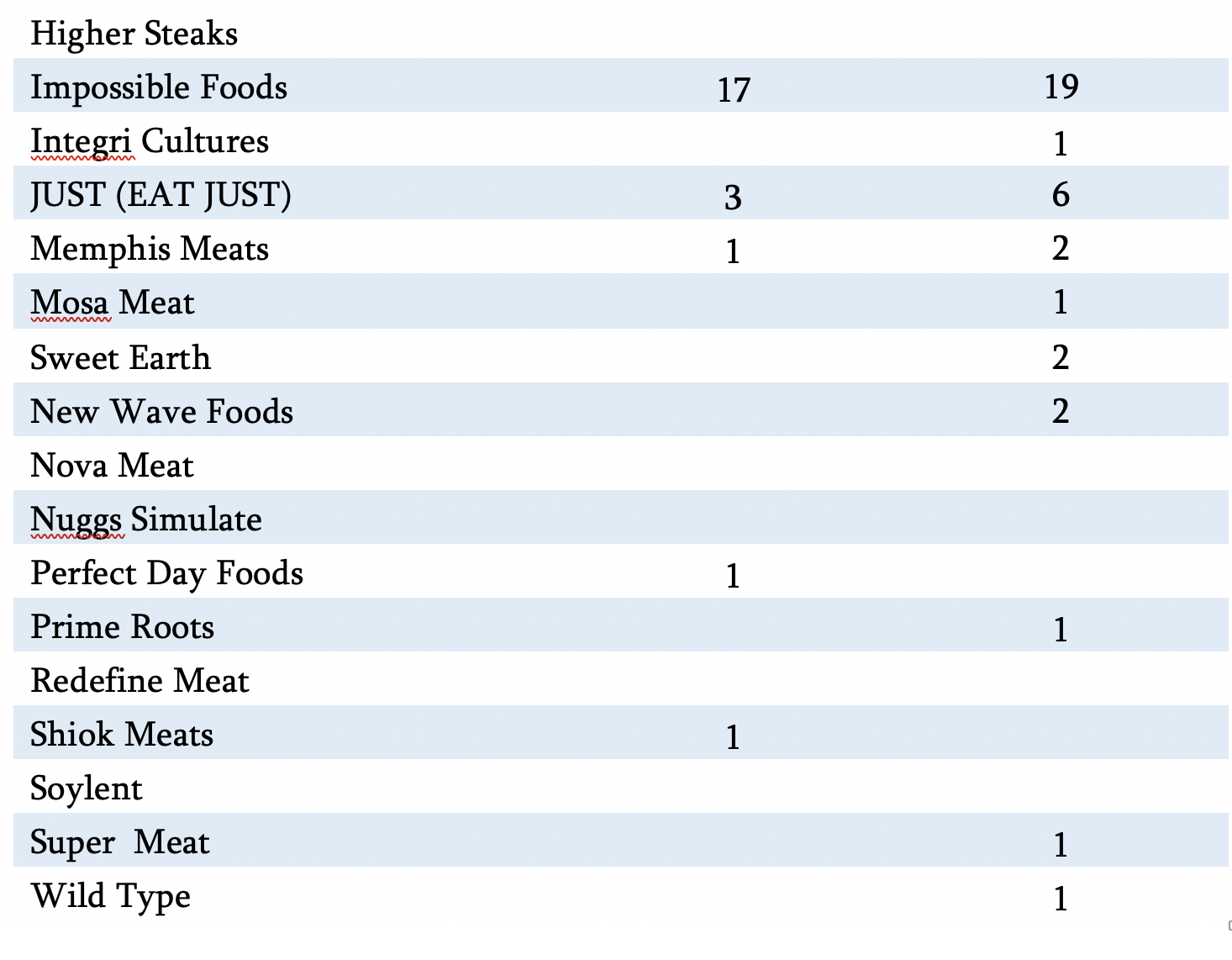

Table 2 gives a summary of the key players and their pursuit of types of patent protection.

This type of breakdown shows that these key players are not only seeking patent protection on the desired final food product, but also protection for processes and products related to making the final food product.

This type of breakdown shows that these key players are not only seeking patent protection on the desired final food product, but also protection for processes and products related to making the final food product.

Closer Analysis of Claim Coverage

As can be seen from Table 2 above, only Impossible Foods to date has a granted patent with pure product claims directed to a cultured/substitute meat product.

Other companies have tried, but failed to obtain pure product claims. Typically product claims have been rejected with the examiner asserting that the claims merely recite “products that use or eliminate common ingredients”, or the claimed combination of ingredients is merely typical “optimization” and there is no evidence that the claimed combination of ingredients results in any “unexpected results”.

So why has Impossible Foods succeeded where others have failed? The answer it seems is based on heme.

Impossible Foods has seven granted product patents (two others about to be granted) with claims to a food product/meat-like food product/meat substitute. The claims in all seven of those patents have one important characteristic – they all claim the presence of a “heme-containing protein”. All of the product claims in these patents (aside from U.S. 10,863,761) have two additional important limitations:

a) the claims further define that the product “contains no animal proteins”; and

b) the claims all recite that cooking the product “results in the production of at least two volatile compounds which have a beef-associated aroma.”

The importance of heme in the Impossible Food products is explained on their website as:

Heme is what makes meat taste like meat. It’s an essential molecule found in every living plant and animal — most abundantly in animals — and something we’ve been eating and craving since the dawn of humanity. Here at Impossible Foods, our plant-based heme is made via fermentation of genetically engineered yeast, and safety-verified by America’s top food-safety experts and peer-reviewed academic journals.

The importance of these limitations in the granted patents can be seen by reviewing the prosecution history of the patents. Prosecution included numerous responses, claim amendments and the submission of several Declarations to support the surprising results achieved by the invention, particularly with respect to the volatile compounds associated with a “meaty aroma”. The claims that were ultimately allowed and granted were much different than the originally filed and published claims, with allowance being granted based on the importance of the above discussed claim limitations, including recitation of a specific soy heme polypeptide and “no animal products”.

Prosecution of further applications gradually became easier for Impossible Foods as the later claims all eventually included these same claim limitations.

So it is rather clear that heme is the key to the granted patents (although not reciting the specific soy protein) for Impossible Foods. While other companies have been met by continued rejections of their product claims, Impossible Foods could emphasize the presence in a “meat-like” product of a non-meat ingredient, namely a plant derived heme. No other company seems to base their patents on the presence of such a particularly unique ingredient.

Lessons Learned

1. Product claims are difficult.

It is clear from a review of the different company patent portfolios that it will be difficult to obtain patent claims to cultured/substitute meat products per se. The inclusion of a new or different ingredient, like Impossible Foods’ plant-derived heme, makes product patent claims easier to obtain. But it will be very difficult to obtain product patents for products based merely on combinations of known food product ingredients.

2. Declaration evidence helps.

The substitute/cultured meat industry is rather new. But the typical product is comprised of known ingredients that are combined in a different way or manufactured in a different way to provide the new product. This scenario is very common in many industries. In the broad “chemical” or pharmaceutical fields, oftentimes the new product is a new combination of known ingredients or is a new compound that is a variation of a known product. Patent applications on such products are very often met with the same kind of rejections being encountered by applicants for meat substitute patents, namely the objection that the claimed product is a mere “optimization” or minor modification of known products without any evidence of an “unexpected result”. Overcoming such rejections often requires some evidence by an expert or person skilled in the art, in the form of a Declaration, reporting on experiments or test results to show something “unexpected” in the claimed invention. Declaration evidence of this type was submitted in several of the Impossible Foods cases and in applications by Beyond Meats.

Companies in this field can expect that successful patent prosecution will often require this type of evidence. It can be an unwanted time burden and expense, but is typical, and often required for success.

3. Take an incremental approach.

Young companies often want to obtain a broad patent to protect against competitors and to show the value of their technology. They see that grant of a broad patent as a way to validate the technology at the core of the company, and to increase value of the company or increase interest in additional investment money. But an incremental approach can oftentimes be more valuable and successful.

This “incremental” approach has been followed by Impossible Foods. The first patent granted to Impossible Foods, U.S. 9,700,067, issued with product claims to a “ground beef-like product”. Those claims are somewhat narrow in that they require the presence of a specific heme-containing compound, namely the soy-derived heme polypeptide having a specific protein sequence, or one having “at least 80% sequence identity”. But Impossible Foods over time filed various continuation/divisional applications, and new applications, to seek a variety of different types and broader claims. Thus, rather than focusing on getting just one or two broad patents, Impossible Foods now has a small “patent thicket” which provides protection for its core technology.

4. Have patience.

Young companies also need to understand that it takes time to build a patent portfolio. Beyond Meat (actually, its predecessor company) filed its first U.S. provisional application in September 2014, and more than six years later only has one granted patent, with nine others still pending. Impossible Foods (or its predecessor) filed the initial provisional patent applications in 2011, so it has taken 10 years for that company to build its patent portfolio, but it has incrementally and patiently created complete families of patents from its two early provisional patent applications.

Patience and perseverance pay off in patent prosecution, as in other areas of business and life.

But all that patent portfolio building does not come free. Well-funded companies like Impossible Foods can better afford such work, but all young companies struggle with the investment costs to build a necessary patent portfolio.

Learn from the Pioneers

Patent protection is vital for young, technology-based companies, both to protect innovation and to attract investment. In the growing substitute meat industry, Impossible Foods has by far had the most patent success, mainly because it bases final product patent protection on the presence of an ingredient not found in other meat products—heme. Other companies would do well to take note of the lessons learned from the experiences to date of the early leaders in this emerging IP field.

An Appendix 1 that summarizes the patent landscape for each of the main companies in this field, and Appendix 2 that gives a detailed analysis of the prosecution actions for the individual patent portfolios and patent applications, explaining the steps taken in the USPTO as the applicants sought (or are seeking) to obtain granted patents are available by request or can be downloaded from the BSKB website, www.bskb.com.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Photography ID:312551700

Copyright:steveheap

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

6 comments so far.

Len Svensson

May 27, 2021 01:24 pmGeorge: Several of the Impossible Food cases did involve one or more RCEs, used to provide extra opportunities to submit more evidence and/or amended claims. But as time went on, and the strategy became more clear, likely also to the Examiner, RCE filings were less needed.

I actually am usually leary of CIPs. If new disclosure in a CIP is needed to support the claims, then that means those claims are not entitled to the original filing/priority date, which opens the door to new prior art issues, including maybe the inventor’s own publications.

ipguy

May 27, 2021 12:14 pm“meaty aroma”

Seems a little vague and indefinite.

George

May 26, 2021 10:29 amSorry, ‘Svensson’ – typing too fast as usual (and no ability to correct posted comments).

George

May 26, 2021 10:27 amWhen it comes to ‘secret recipes’, isn’t it better to just try to keep those a trade secret (at least for marketing purposes)? I suppose keeping the most important and easily discoverable ingredients would be impossible though, so patents would be the only option then.

The ‘tricks’ used to create massive amounts of cultured meat cells could maybe be kept secret, though, especially if it involves adding special enzymes, nutrients or other ingredients and processes that wouldn’t be divulged in the final product. Indeed ‘methods’ for obtaining the final product (in large quantities) might be much better protected with trade secret (for much longer). That’s where the ‘quantity’ of product able to be produced may obtain it’s own ‘quality’, as suggested by Svennson.

George

May 26, 2021 10:13 am‘insight’ – not ‘incite’! Sorry.

George

May 26, 2021 10:09 am“Patience and perseverance pay off in patent prosecution, as in other areas of business and life.”

Did they file RCE’s or CIP’s? That’s an important incite. Most practitioners don’t advise filing CIP’s (at least not more than once). We NEVER file RCE’s! We file CIP’s in order to ‘broaden’, not narrow, our claims (or at least maintain the original scope).