Grappling dummy and production thereof

Grappling dummy and production thereof

US Patent No. 6,139,328

Issued October 31, 2000

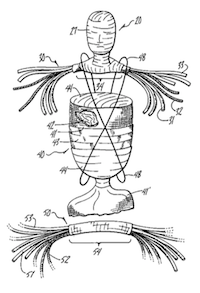

This is a patent that I have used for years when teaching law students the art of patent application drafting, particularly claim drafting. As you can see from the picture, this invention is a grappling dummy. This dummy meets the utility requirement because it is used for exercise or practice by athletes training for competitive martial art or wrestling.

Perhaps this is not your idea of a “useful” invention, but the utility requirement, which is one of the so-called “patentability requirements,” is satisfied if the device that is claimed in the application can be used for the purpose described. Here the inventor has quite clearly provided a useful invention, at least in so far as the patent law is concerned.

Not that it is necessary to satisfy the utility requirement, but this patent goes further relative to utility. The patent explains: “The grappling dummy is useful for exercise or practice for athletes training for competitive martial art or wrestling purposes, as well as for practicing self-defense moves.” This is relatively obvious from the general disclosure and as such wouldn’t actually be necessary to say. Utility is a threshold requirement meaning there needs to be a utility, but the utility can be express, implicit or even inherent. For example, if you invented a new and improved hammer you wouldn’t really need to explain what it is useful for. Notwithstanding, you probably really should explain the utility of the invention explicitly. Just be sure not to do it in a way that makes it sound like what you are describing is the only utility.

On its face it is hard to immediately reach the conclusion that this “invention” is not or should not be patentable, which is why it is not going into the Museum of Obscure Patents, but there are a couple learning opportunities available.

[Enhance]

First, if you look at the patent you will notice that in Column 1 there is a section labeled “Background and Summary of the Invention.” I am not a fan of this presentation, particularly after the United States Supreme Court’s decision in KSR v. Teleflex, which has caused most patent attorneys to become even more cautious relative to the Background section of a patent application. Regardless of KSR, I am not big on this presentation because the Background and the Summary play two different roles in the patent application. The Background is where you discuss the prior art and the Summary is where you discuss your own invention in a nutshell, or executive summary fashion. Where does the Background end and the Summary start? While this OK in this case given the relative simplicity of the invention and that there really is no particular discussion of the prior art, best drafting practices are not to mix the two together. Keep them separate. They serve different purposes and you don’t want an angry patent litigator dissecting something so simple as your opening paragraph.

Second, the patent goes on to explain that an inventive aspect of the invention is that the weight of the grappling dummy is diminutive relative to its stature. The patent explains:

An inventive aspect of the grappling dummy is that, for a given stature, if it is given for example a stature of about five foot ten inches (178 cm) tall, then the weight of grappling dummy is correspondingly given a relatively diminutive weight:–e.g., somewhere in the neighborhood of forty pounds (18 kg) or so. It has been discovered that giving the grappling dummy such a relatively diminutive weight (relative to its stature) happens to just “feel” right to the user who is practicing or exercising with the dummy. In other words, whereas the grappling dummy is given a proportionate height for a practice opponent, it is given a grossly diminutive weight.

My issue with this paragraph is slight, and many will likely see it as quite picky. When you say “an inventive aspect of the invention is,” what do you mean? Is this the only inventive aspect of the invention. You want to be extremely careful whenever you start talking about inventive aspects of your invention. If you say “the inventive aspect of the invention is,” you may be seen as limiting yourself and admitting that your invention has but one inventive aspect. The importance of this is that if the patent examiner finds that one inventive aspect in the prior art they will use your disclosure coupled together with the found inventive aspect to fashion an obviousness rejection that will be exceptionally difficult to overcome.

The grappling dummy patent does, however, broaden past this diminutive weight inventive aspect to later say that there is an inventive knee construction strong enough that the knee will not extend past straight. Further, the patent explains that “a substantial inventive aspect” is that the joints of the dummy all hold their angle of articulation until a sufficient applied forces flexes or extends them to a changed position. While these additional “inventive aspects” are quite helpful because they do identify what the inventor thinks is unique and doesn’t limit the patent application to a single inventive aspect, it would probably be better to use squirrely lawyer words and phrases like: “while there are many unique aspects of the invention, one particularly unique aspect of certain embodiments of the invention is that…” You get the idea. You never want to box yourself into a corner saying, or at all implying, that there is one or a limited number of unique aspects to your invention.

Finally, the claims to the grappling dummy patent seem to have a large number of elements and a great level of specificity, even in the broadest claim. For example, claim 1 states:

1. A grappling dummy comprising:

a torso having a semi-rigid abdominal wall extending between upper and lower ends;

a bi-lateral arm assembly;

a bi-lateral leg assembly;

each of the bi-lateral arm and leg assemblies comprising:

a bundle of flexible strand elements,

generally rigid left and right upper-limb members disposed on the bundle flanking a gap that defines one of a shoulder portion and a hip portion therebetween correspondingly for the arm assembly and leg assembly, respectively,

generally rigid left and right lower-limb members disposed on the bundle flanking the left and right upper-limb members, respectively, and respectively defining therebetween correspondingly for the arm assembly and leg assembly, left and right elbow joints and knee joints, respectively,

attaching means for attaching the upper- and lower-limb members to the bundle between various strands thereof and allowing relative movement in the respective elbow or knee joint,

resistor means associated with each elbow or knee joint for limiting the articulation in the associated elbow or knee joint substantially to flexion and extension only, and providing frictional resistance to the flexion and extension movements of the associated elbow or knee joint, and,

stop means associated with each elbow or knee joint for stopping extension movement in the associated elbow or knee joint at a given limit that corresponds to hyper-extension thereof;

arm assembly mounting means for mounting the shoulder portion thereof to the upper end of the torso and allowing movement at left and right shoulder joints thereof;

leg assembly mounting means for mounting the hip portion thereof to the lower end of the torso and allowing movement at left and right hip joints thereof; and,

hip resistor means associated with each hip joint for limiting the articulation in the associated hip joint substantially to flexion and extension only, and providing frictional resistance to the flexion and extension movements of the associated hip joint.

Such a long, detailed and narrow feature set may have been require to get a patent issued, but is the patent effort (i.e., time and cost) worth such a narrow set of claims? The answer can be a resounding YES, or a definite NO! It all depends upon what you want to do with the patent. One this is for certain though, if you add enough qualifiers and sufficiently narrow a claim you can get a patent on virtually anything, which is unfortunately a truth that invention promotion companies know all to well! In almost all circumstances the goal is to get the broadest valid claim you can possibly obtain. Getting a narrow claim is not likely going to be satisfying, which is why you really should do a patent search prior to deciding whether to even move forward with a patent application. Only by doing a patent search can you get any idea regarding the likely scope of patent claims that could be obtained.

In the situation where the only patent that can be obtained includes claims with great specificity, such as this one, obtaining a patent is likely not going to provide the type of strong protection that one would normally associate with a patent. True, the inventor of this patent will enjoy exclusive rights with respect to that which is claimed. The question, however, is whether the exclusive rights are so narrowly defined such that competitors could engineer around the patent. If your patent covers a successful product there will be market entrants who will seek to engineer around, and if your patent allows that to happen then the return on your investment does not provide the expected yield.

The morale of the story is this — you always need to consider what you want to do with a patent once it issues. If you want it to scare off competitors and maybe encourage consumers because you can say you have a “patent pending,” then any patent could be worthwhile, depending of course on financial costs.

For more information on patent application drafting please see:

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

2 comments so far.

Inventor0875

August 22, 2011 12:04 amFor fun: It would be interesting to see various imaginative “design-around” from the blog readers.

What elements/features would you remove/change in claim 1 above and still have customers for your non-infringing design-around version ?

Erin-Michael Gill

August 20, 2011 06:56 pm“Such a long, detailed and narrow feature set may have been require to get a patent issued, but is the patent effort (i.e., time and cost) worth such a narrow set of claims? The answer can be a resounding YES, or a definite NO! It all depends upon what you want to do with the patent.”

Nice post Gene – people really need to spend more time asking inventors: so how is this patent going to be used…