A little less than one year ago the United States Supreme Court issued its decision in Alice v. CLS Bank, setting off a whirlwind reaction. In a unanimous decision authored by Justice Thomas the Supreme Court held that the patent claims were drawn to a patent-ineligible abstract idea, thus they were not eligible for a patent under Section 101. Despite the fact that the claims involved were directed to software (i.e., software patent claims) the Supreme Court did not use the word “software” in the opinion. Nevertheless, the future for software patents has been dramatically altered.

A little less than one year ago the United States Supreme Court issued its decision in Alice v. CLS Bank, setting off a whirlwind reaction. In a unanimous decision authored by Justice Thomas the Supreme Court held that the patent claims were drawn to a patent-ineligible abstract idea, thus they were not eligible for a patent under Section 101. Despite the fact that the claims involved were directed to software (i.e., software patent claims) the Supreme Court did not use the word “software” in the opinion. Nevertheless, the future for software patents has been dramatically altered.

Since the decision by the Supreme Court, Alice has been used to reject software patent claims as being patent ineligible by the Federal Circuit, numerous district courts, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) and patent examiners at the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). Indeed, the Alice decision has infused a great deal of uncertainty into the law of patent eligibility. The level of uncertainty can perhaps best be exemplified by the fact that the Federal Circuit issued what appear to be diametrically opposed opinions in Ultramercial and DDR Holdings.

Numerous patents have been lost with claims invalidated as being patent ineligible in the wake of Alice. This has negatively affected patent valuation, rendering many patents worth far less if not completely worthless. this has led some commentators to lament the toxicity of the patent asset and question whether the the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has the bandwidth to cope with the increased time demands placed on patent examiners as they navigate the patent eligibility issue in as many as 50% of all pending patent applications.

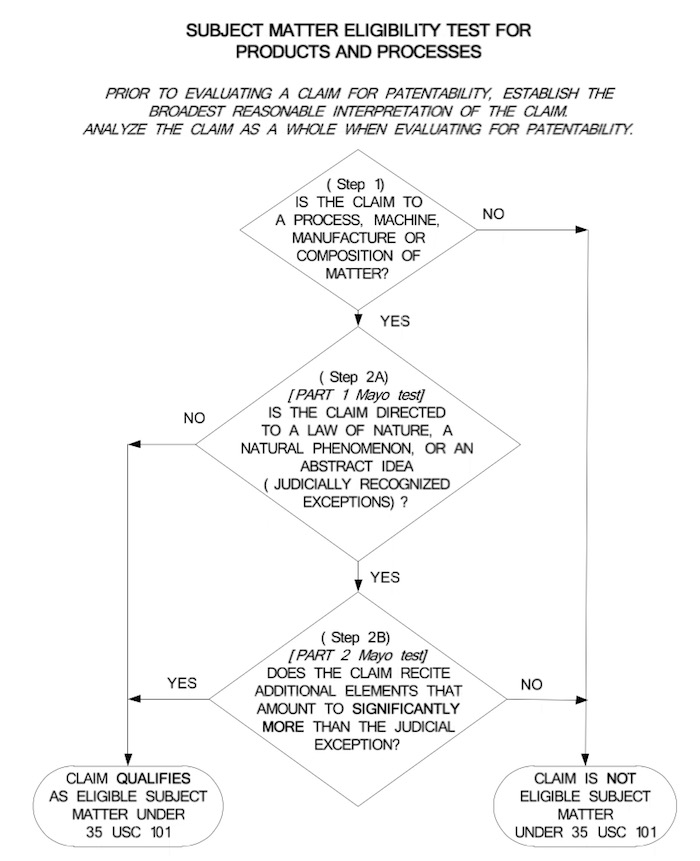

In December 2014, the USPTO provided interim guidance on patent eligibility. The guidance provided the below flowchart to describe the two-step analysis required when patent examiners are confronted with software patent claims.

The USPTO further attempted to mitigate the Alice disaster by publishing hypothetical examples of when software patent claims should be deemed to be patent eligible. Unfortunately, it seems to many practitioners that at least some examiners are simply not following what the Office has told them to do.

Reports suggest that some patent examiners are going through both parts of the Mayo analysis even when Step 2A of the analysis clearly requires a finding that the claim is patent eligible. While I do sympathize greatly with the examiners given the tumultuous past few years, with no fewer than 19 substantive changes to patent law according to an Inspector General from the Commerce Department, there is no excuse for continuing on to Step 2B of the inquiry if the patent claims are eligible under Step 2A. Unfortunately it seems that many patent examiners and judges alike are channeling the Supreme Court and attempting to determine how they may view a particular patent claim rather than independently applying the test. This has led to great uncertainty, which has led many to question the future for software patents.

I do feel for the Patent Office and patent examiners because I don’t know how they can really rationalize the Federal Circuit’s rulings in Ultramercial and DDR, at least not the way that patent decisions have historically been rationalized. While there are ways that you could distinguish Ultramercial from DDR, I don’t think you can honestly rationalize these two decisions by looking at the patent claims. The patent claims are structured in a similar way. There was a thicker technical disclosure in the patents that were an issue in the DDR case, but a thicker specification should be properly treated under 35 U.S.C. 112, not as a patent eligibility issue under 35 U.S.C. 101. The future for software patents, although tied to patent eligibility under 101, seems more directly linked in an analytical way to sufficiency of disclosure under 112 and obviousness under 103.

Normally when there is a rejection the innovation itself has not been rejected, but rather the particular way in which it has been claimed is found to be unacceptable for one reason or another. The insidious nature of patent eligibility rejections, however, is that that innovation itself is rejected without regard to whether the innovation is useful, new, non-obvious and described well enough. A finality in the decision making process is reached even before any substantive inquiry is made about the nature and quality of the innovation. Such cursory decisions at the front end, without any factual inquiry into the merits of the invention, can render an entire category of innovation dead on conception, which is why patent eligibility has always been historically viewed as a low threshold inquiry, not the insurmountable mountain that it has become.

There never should be difficult decisions under 101. If there isn’t an easy, obvious decision that would render the innovation patent ineligible then patent examiners, and Judges, shouldn’t seek to use 101 to immediately render the entire innovation patent ineligible. In many regards this type of decisional approach is reminiscent of the “earth is flat” crowd, who couldn’t be bothered with considering new information and instead clung to irrational notions in the face of evidence to the contrary. What scientific research and technological pursuits will be stopped by a patent eligibility requirement on steroids? We have already significantly deterred R&D into genes, medical diagnostics and software. Amazing really, but this Supreme Court will go down as one of the most science phobic courts of all time.

Using 35 U.S.C. 101 to render an innovation patent ineligible is not only myopic in the extreme, but it is also akin to using an elephant gun to kill a mosquito. The proper analysis has historically allowed the other sections of the statute due the work for which they were intended. If there is anything in the disclosure that satisfies 35 U.S.C. 112 then look at the claims through those eyes as you determine whether the claims are novel under 35 U.S.C 102 and non-obvious under 35 U.S.C 103. Patent eligibility should only be used as an impediment in the most extreme, egregious cases. It is simply inappropriate, and rather stupid, to allow innovations to be weeded out before anyone actually considers whether there was a disclosure that adequately teaches a new and non-obvious innovation.

Historically the USPTO always preferred to issue a patent when in doubt rather than bury the innovation that otherwise could have led to things that we could never have known. Stopping an innovation at the gate prevents investment, which places a strangle hold on the technology and kills further research and development. Unfortunately, somewhere along the way we got away from that understanding. Perhaps it was under the Bush Administration with so-caled “second pair of eyes” review, and if you recall that was largely a response to New York Times, NPR and other media outlets making fun of certain patents that had issued, for example the patent on the swing that went sideways. So the response was that the Patent Office was never going to let anything that shouldn’t have issued ever issue again. Well, silly patents don’t issue as often as it once did, but by having the filter so high you wind up catching a lot more than what you really should.

But this leads us to the real reason that 101 is such a hot topic — by forcing patent eligibility to perform a stringent gatekeeping function district court judges can get rid of many patent cases on a motion to dismiss without any discovery. The Supreme Court seems exceptionally interested in the patent troll that’s not really in front of them in the cases they are deciding, and they are trying to deal with abusive litigation despite that not being an issue. Yes, there are bad actors in the industry, but making the patent eligibility inquiry the ultimate test is not a productive way to do anything other than weed out innovation at its earliest stages before it has ever been evaluated for novelty or obviousness, and in many cases before it has ever had an opportunity to show its value in the marketplace.

As odd as all the machinations over software patents have been, the one thing that strikes me as most bizarre is how the courts continue to cling to the ridiculous, nonsensical distinction between a general purpose computer and a specific purpose machine. This isn’t a distinction without a difference, but rather it is a distinction for those without a clue. The real value in software is that it operates across platforms. If you want to fire up an Apple computer you’re going to be able to use compatible software, if you’re going to fire up a PC you’re going to be able to use the same compatible software regardless of what other software you might be using. Yet, interoperability and compatibility seems to literally make software less likely to be patent eligible because it works on any type of machine. Well, that is of course the point. If you say that out loud it sounds strikingly ridiculous, yet judges write it all the time as if the more they write it somehow it will eventually become true.

That fact that software works on any machine, at any time, in any environment is where the value resides. To even suggest that interoperability and compatibility somehow makes the software routine is among the most ridiculous things anyone has ever thought, said or written. It shows such a lack of familiarity with the fundamental underpinnings of software that anyone who has such a childish view of the technology should be deemed unfit and not competent to decide issues involving the technology.

As we approach the first anniversary of the Alice decision, the future of software hangs in the balance. Ultimately I have no doubt that software will be declared to be patent eligible either by the Congress or the Supreme Court, but it took the Supreme Court nine (9) years to retreat from their first misguided software patent decision in Gottschalk v. Benson. Congress seems wholly incapable of doing anything that would remotely be in the best interest of the patent system. Thus, the immediate future for software patents seems murky. Certainly there are ways forward, but the way forward is not cheap, it is not easy, and it will likely be long and arduous. Gone are the days that a patent on software could be quickly and cheaply obtained. To be worth anything in the long run great care must be made to disclose the technology with an overwhelmingly detailed specification. Narrowly tailored claims should be sought, but with plenty of support to circle back for broader protections once the courts have come to their senses on software, which makes up at least 50% of all innovation today.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[[Advertisement]]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-1.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

6 comments so far.

Nelson Avek

September 23, 2015 09:04 amA question was asked to a patent examiner, the question was –

Do you see a future where software patents do not exist?

His answer: ” Can I? Sure.

Do I? Not really. Laws are slow to change, and we just had major reform. The courts generally nudge in a direction, and I doubt they would just go and invalidate all those patents. It would cause a lot of chaos, and a lot of big companies would not be happy.

This is completely just my opinion, but over the next 10 years you will see less and less “bad” software patents coming out. Why? Because examiners will have a body of prior art to pull from. There was a big problem where there was a complete void of any prior art that examiners could use, so they couldn’t reject even stupid stuff. ”

That’s what he said. We can see a no-software-patent-future, but that is nearly impossible as, we can’t eliminate the existing good patents which were worth filing.

Let’s leave it on future only.

And yes, you can read the full Question/Answer session from here –

http://www.greyb.com/11-answers-help-understand-how-patent-examiners-work/

These are total 11 question, answered by a patent examiner which can help you better understand their way of work.

Paul Cole

June 1, 2015 02:06 amAs I have pointed out on numerous occasions, my friend Keith Beresford who is one of the ablest patent attorneys practising before the EPO was not able to obtain grant of the European patents that came in issue before the Supreme Court, and the applications were abandoned without even a hearing before the Examining Division. In the absence of any clearly identifiable technical effect sufficient to convince the EPO as to eligibility, pursuing the US patent to the Supreme Court was an ill-advised venture.

SoftwareForTheWin

May 31, 2015 06:16 pmSaint Cad:

Nail on head.

For an individual/startup, given all of the patent changes over recent past, the ROI of any resulting patent(s) will be significantly decreased from previous history. Any potential licensees have much greater chances of finding a way to weasle out of paying any licensing $fees. Really, the $20k is only the beginning of the costs of choosing to go down the patent road (Alice, Post Grant Reviews, induce others to infringement Akamai vs Limelight, Ebay, appeals, …the list goes on and on and on…).

In many cases today (given the realities of 2015 patent climate), that $20k can be better allocated elsewhere. Indeed, numerous success stories of startups that have forgone relying on patents exist.

Saint Cad

May 27, 2015 08:26 pmHere’s the quandry I’m in and I’m sure many other are as well. I’m all set to file a provisional patent for a software “idea” that I have but am I ready to spend $20k for a non-provisional patent that may be rejected? Add to that if I do the customary process of filing the provisional patent and start to market/sell my idea for money to pay for the patent, will companies rely on Alice to say no thank you and try to steal my idea? Why would any small inventor take that risk now, especially as with the year deadline we don’t have time to wait for the next SCOTUS ruling.

EG

May 27, 2015 08:10 am“The Supreme Court seems exceptionally interested in the patent troll that’s not really in front of them in the cases they are deciding.”

Gene,

Absolutely correct. Our Royal Nine makes a judgment based on NO FACTUAL RECORD before it to support that judgment. And people wonder why we patent attorneys generally have no respect for Our Judicial Mount Olympus?

“[T]he one thing that strikes me as most bizarre is how the courts continue to cling to the ridiculous, nonsensical distinction between a general purpose computer and a specific purpose machine.”

Gene,

Another absolute truism. The software modifies the operation of that computer, and without software to run it, that computer is pretty much a worthless desk ornament. The Royal Nine are embarrassing in not understanding computer basics that even are kids know.

Ronni

May 27, 2015 07:58 amThank you for your comments. I completely agree. I just responded to a 101 rejection of claims directed to a system, where the examiner took the position that because the system could be implemented entirely by software, it was patent ineligible because it was not directed to one of the four classes of patentable subject matter set out in 101. The PTO rejections are out of control. IMHO