Agriculture is a huge industry in the state of California. In 2012, California’s $45 billion in farm-level sales accounted for 11 percent of total U.S. agricultural sales, with five of California’s counties (Fresno, Monterey, Tulare, Kern and Merced) found among the nation’s leading agricultural counties. Corn, cotton, rice, wine grapes, citrus and walnuts are just a few of agricultural products produced in the Golden State. As we here at IPWatchdog have written before, California’s irrigation system for agriculture relies heavily upon a system of dams and reservoirs bringing water from Lake Shasta and other sources in the northern regions of the state down towards southern, more arid regions.

December 6th marks the anniversary of a patent issued nearly 130 years ago for a crucial technological advance that played its part in turning California into the farm producing giant it is today. The story of its inventor, Harriet W.R. Strong, is a reminder of the incredible resilience that most innovators show in the face of adversity, whether those challenges are life or work-related.

Born July 1844 in Buffalo, NY, Harriet Russell had already moved with her family to California by the time she was in school, studying at a seminary in Benicia, CA. From an early age she was plagued by spine issues that would follow her throughout her life. In her late teens she met Charles Lyman Strong, a mining superintendent whom she married in 1863. A series of breakdowns in Charles’ physical and mental health, as well as a string of business losses, weighed heavily upon him. He took his own life in 1883, leaving Harriet as a widow and single mother of four daughters at the age of 39.

Hassled by growing financial concerns, including legal matters from Charles’ business failures, and still battling chronic health problems, Harriet became determined to turn the family’s 220-acre farm, Rancho del Fuerte, into a profitable one. Situated near what is now Whittier, CA, the ranch sat on land that was arid but could still produce fruits, nuts and pampas grass. It wasn’t until after Charles’ death that Harriet took charge of the farm, when she began experimenting with the crops which could be grown at Rancho del Fuerte. She also began her own personal studies on irrigation, horticulture and the various prices that different crop commodities could fetch at market.

Eventually, Strong settled upon the walnut as her main commercial crop, finding it to be the most profitable crop she could grow on her farm. The cultivation of walnuts, as with many nuts grown from trees, requires a great deal of water for proper irrigation; by some measures, as much as five gallons of water are needed to produce a single walnut. To provide this water to her walnut crops, Strong would develop a string of irrigation and water storage systems which would prove to be remarkably successful. In a few years’ time, she became America’s leading commercial grower of walnuts, turning around her family’s finances and earning herself the nickname “the Walnut Queen.” Strong maintained about 150 acres of walnut trees providing an average yield of $295 per acre; in 2014 dollars, that’s nearly $8,000 per acre.

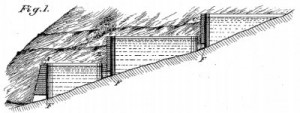

On December 6th, 1887, Strong was issued U.S. Patent No. 374,378, titled Dam and Reservoir Construction, from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. It claimed an improvement in collecting and retaining water consisting of a series of reversed arched dams built one above the other in an inclined channel or valley so that the water in each lower dam acts as a brace or support for the dam above; the series of dams was connected by gates. This irrigation innovation allowed for lower-strength dams to be used higher up in the dam series and worked to save water in steep inclines or valleys instead of letting it drain away. In 1893, Strong won agricultural and mining awards for an improved dam design when she exhibited it at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

On December 6th, 1887, Strong was issued U.S. Patent No. 374,378, titled Dam and Reservoir Construction, from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. It claimed an improvement in collecting and retaining water consisting of a series of reversed arched dams built one above the other in an inclined channel or valley so that the water in each lower dam acts as a brace or support for the dam above; the series of dams was connected by gates. This irrigation innovation allowed for lower-strength dams to be used higher up in the dam series and worked to save water in steep inclines or valleys instead of letting it drain away. In 1893, Strong won agricultural and mining awards for an improved dam design when she exhibited it at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

The late 19th century was a very important time in the development of California as an agricultural powerhouse. Attempts at major construction projects in California irrigation go back to before the Civil War but a major impetus for water development came from the federal government in 1873 when then-President Ulysses S. Grant commissioned an investigation by the Army Corps of Engineers to survey California’s Central Valley region. That report recommended the development of watersheds in California’s mountainous Sierra region. The half-century between 1870 and 1920 also saw the majority of the development of the Central California Irrigation District, which today provides irrigation to more than 1,600 farms spanning across an area greater than 143,000 acres.

In 1887, the state of California passed the Wright Act, which created public irrigation districts. Major engineering projects wouldn’t get underway, however, until early in the 1900s. Although irrigation was important in northern areas of the state, San Francisco was established in an area with little available water and southern California was practically a desert. Monopoly and price gouging typified the water industry in San Francisco until the Raker Act of 1913 gave the city the right to dam the Hetch Hetchy Valley to provide water for drinking and irrigation. The Owens Valley Water Project, which still causes some controversy to this day, resulted in the 1913 completion of the Los Angeles Aqueduct, which diverted water from Owens River. Early development of irrigation systems taking water from readily available sources in northern California down to the semi-arid and desert conditions of the southern regions of the state would eventually coalesce into the Central Valley Project, which covers a nearly 500-mile stretch of watershed running through California ranging in width from 60 miles to 100 miles at various points. All told, it contains 20 dams and reservoirs, 11 power plants and hundreds of miles of canals.

As for Strong, her ability to engineer a solution to watering her crops was bolstered by the strong business sense that she possessed. She found a market for pampas grass, a flowering plant used for decoration, in national political conventions for both Democrats and Republicans during the 1892 and 1896 election years. She found success on the East Coast in Philadelphia, where more than 130,000 pampas grass plumes were sold at Wanamaker’s department store. She was also dedicated to feminist causes, working to help organize a Ladies Business League of America. In the fight for women’s suffrage, Strong would travel along with Susan B. Anthony and other feminist leaders to promote the cause across the United States.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

No comments yet.