Throughout the majority of prosecution, Applicants face one decision-maker: the Examiner. The Applicant and Examiner can communicate on paper via written office actions and Amendments or verbally via interviews. Rejections can be explained, arguments presented, and claims amended. But at times, this exchange reaches a standstill, where the parties cannot agree on whether the pending claims are patentable. Applicants can then choose whether to initiate an ex parte appeal process, which would allow the Applicant to present their case to other decision-makers, namely the Patent and Trial Appeal Board (“PTAB” or “the Board”).

Throughout the majority of prosecution, Applicants face one decision-maker: the Examiner. The Applicant and Examiner can communicate on paper via written office actions and Amendments or verbally via interviews. Rejections can be explained, arguments presented, and claims amended. But at times, this exchange reaches a standstill, where the parties cannot agree on whether the pending claims are patentable. Applicants can then choose whether to initiate an ex parte appeal process, which would allow the Applicant to present their case to other decision-makers, namely the Patent and Trial Appeal Board (“PTAB” or “the Board”).

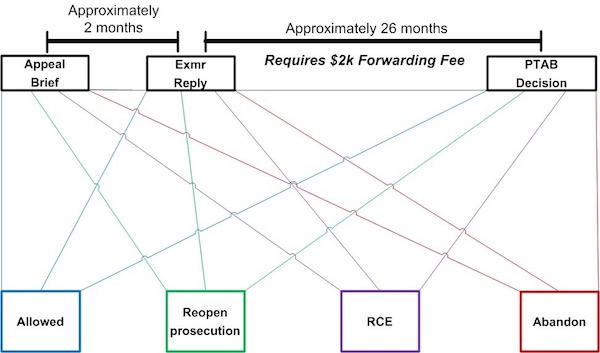

The appeal cycle includes several stages. A Notice of Appeal must first be filed, and the Applicant (then also referred to as the “Appellant”) has two months to file a full Appeal Brief that includes arguments. An Examiner is then to reply with an Examiner’s Answer, which is supposed to be issued within two months from the Brief. The Appellant has an option to (but need not) respond to the Examiner’s Answer with a Reply Brief. As of March 19, 2013, Appellants must also pay a forwarding fee at this stage. The PTAB then considers the presented arguments and issues a decision.[i]

Despite the attraction of engaging different decision-makers, traditionally, appeals are viewed as being associated with two prominent (often undesirable) consequences: long delays and cost. In 2013, the average delay between an appeal being received at the PTAB and issuance of a decision was 26 months.[ii] At present, for large entities, the USPTO fee for filing the Notice of Appeal is $800 and the forwarding fee is $2,000. Further, the median attorney fees for preparing the Appeal Brief is $5,000.[iii] However, it is important to recognize that these delay and expense consequences primarily occur when an appeal completes a full cycle.

As illustrated in Figure 1, each party (the Appellant and the Examiner) has the maintained opportunity throughout the appeal cycle to pull the application out of the appeal cycle. The Appellant can file a request for continued examination (RCE) to return to normal prosecution or can abandon the application. The Examiner can issue a notice of allowance or a new office action. These Examiner actions present an opportunity in which an appeal cycle may end prematurely, which may (and often would) decrease the delay and cost of the cycle.

Thus, we set out to study the life cycle of appeals by conducting a stage-by-stage analysis to identify what fraction of applications were exiting the appeal cycle and how. Specifically, we obtained data (using LexisNexis® PatentAdvisorSM) corresponding to each appeal brief filed between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2011. The data identified the stage at which the appeal exited the appeal process and the next significant event after exiting the process. This assessment thus provides information pertinent to assessing what delays, costs and decision outcomes are truly associated with appeals. (See also our corresponding article published in ABA’s Landslide.)[iv]

[Varsity-1]

Exits After Appeal Brief are Rather Common

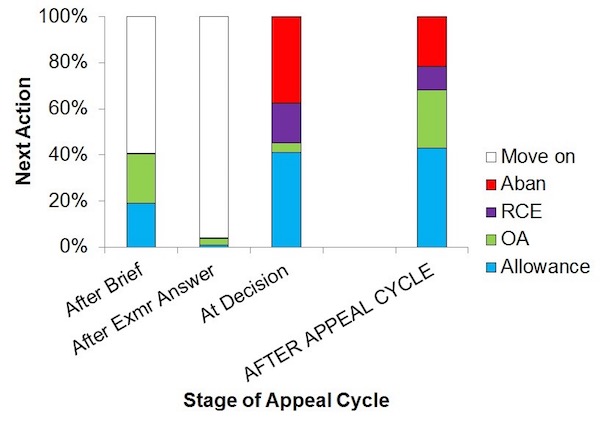

The first bar in Figure 2 illustrates what is likely to occur after an Appellant has filed an Appeal Brief. The data indicates that a substantial 19% of Appeal Briefs lead to the Examiner quickly allowing the application (blue portion of first bar). Another 21% were pulled from the appeal cycle by the Examiner via an office action (green portion of first bar). The post-Brief allowances and office actions were issued relatively quickly (on average: 3 months after the Brief), such that the multi-year delay was avoided. With the current fee structure, these Appellants also would have avoided the substantial PTO forwarding fee ($2,000 for large entities).

Given that a substantial portion of Briefs result in issuance of new office actions, we further explored the statuses of these applications. Were they left in a prosecution purgatory, or did prosecution become more fruitful? Most of these applications had been subsequently allowed, with 59% of the applications being patented. Another 15% were still pending and 26% were abandoned. In total, across all applications for which the appeal cycle was terminated after the Brief, 77% of the applications had a patented status.

Exits After Examiner’s Answer are Rare

For the remaining 60% of appeals (those that “Move On” and that are represented by the white portion of the first bar), an Examiner’s Answer is issued. The vast majority of appeals having received an Examiner’s Answer move on to be considered by the Board (white portion of the second bar): Appellants filed an RCE or abandoned an application only 0.2% of the time following issuance of an Examiner’s Answer.

It is unsurprising that Appellant-initiated appeal exits are rare after filing a brief, as an Appellant recently made a decision to invest in preparation of an Appeal Brief. Further, during the time period our data was taken (between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2011), no fee was required to forward the appeal brief to the PTAB. Today, however, large entities must pay a $2,000 forwarding fee[v] to submit an appeal to the PTAB for consideration (after filing of the appeal brief and receipt of an Examiner’s Answer). Despite this additional fee, a separate analysis of ours has shown that such Appellant-initiated withdrawals remain uncommon (approximately a 5% withdrawal rate responsive to Examiner Answers issued in calendar year 2014). This decision to continue onwards may be due to the past investment in attorney fees to draft the Appeal Brief and encountering no new arguments from the Examiner in the Answer.

Appeal-Cycle Exits At Board Decision: Approximately 50% Reversal/Reversal-in-Part Rate

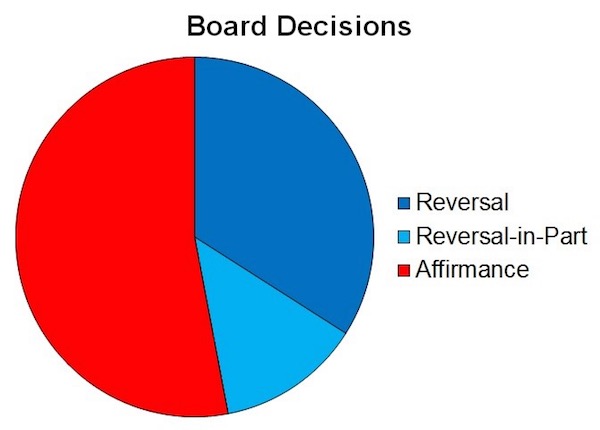

Of those appeals that reach the Board, 41% of the PTAB decisions led to a next-action allowance (blue portion of the third bar), while 38% were followed by an abandonment (red portion of the third bar). The next events are not precise reflections of the PTAB decision. Thus, we also examined the distribution of the decisions: 34% of the PTAB decisions were reversals; 13% were reversals-in-part; and 53% were affirmances. (Figure 3.)

Interestingly, the average Examiner allowance rate among appeals reaching the PTAB is 50%. It is worth recognizing that the “similarity” between these probabilities (of at least partial PTAB reversals and of Examiner allowance) may be misleading. It is our opinion that (on average) potential Appellants’ allowance prospects in front of their Examiner are lower than the Examiner’s reported allowance rate. For example, the fact that the Applicant is considering the appeal suggests that an impasse has been already reached with the Examiner. Further, the Examiner’s refusal to have already allowed the application may suggest that the patentability of the application is more questionable than of other applications that the Examiner has allowed.

Conclusion

Frequently, when an Applicant considers whether to appeal a rejection, the benefits and drawbacks of a full appeal are considered. Presently, the Applicant would consider the fee as the attorney fees, the PTO Notice of Appeal fee and the substantial forwarding fee, and the Applicant would consider the multi-year delay of receiving a decision. Our data indicates that, while these considerations remain relevant, they are not the end of the story.

Rather, Examiners frequently terminate an appeal cycle expediently with an office action (often leading to an allowance) or an allowance, in which case the delay and a portion of the expense is avoided. Such changes of an Examiner’s heart may be a result of engagement of the Examiner’s supervisor. Specifically, an appeal conference between the Examiner, the Examiner’s supervisor, and another Examiner (known as a conferee) is required in response to filing of a compliant Appeal Brief.[vi] Similar conferences are required in response to filings of Requests for Pre-Appeal Brief Conferences, so it is possible that the distribution of post-Brief examiner responses mirror a distribution of responses to Pre-Appeal Brief requests.[vii]

Should an Application endure a full appeal cycle, our data indicates that approximately half of the appeals are at least partly reversed by the Board. This is approximately equal to the average allowance rate of the Examiners examining the application. However, a selection bias would suggest that the applications with weaker patentability arguments are more likely than others to be reviewed by the Board. Meanwhile, frequently, the Board issues only partial reversals, in which case a rejection of one type may prevent a claim from being allowed despite a reversal of another type of rejection, or an allowable claim may be of undesired scope.

Thus, we emphasize that data is nuanced. Just as it is important to be cognizant of applicants’ unique objectives for a given application, it is also important to recognize the complex distribution of potential outcomes of engaging in the appeal cycle.

_______________

[i]. For a related discussion on promoting predictability and consistency of PTAB decisions, see Kate S. Gaudry & Thomas D. Franklin, Only 1 in 20,631 Ex Parte Appeals Designated as Precedential by PTAB, IPWatchDog, Sept. 27, 2015; see also Kate S. Gaudry & Justin Krieger, The Patent Bar’s Role In Setting PTAB Precedence, Law360, Sept. 10, 2015, available at http://www.kilpatricktownsend.com/~/media/Files/articles/2015/The%20Patent%20Bars%20Role%20In%20Setting%20PTAB%20Precedence.ashx.

[ii]. E-mail from U.S. Patent & Trademark Office, to Kate Gaudry, Attorney, Kilpatrick Townsend & Stockton, LLP (Aug. 20, 2015) (on file with author).

[iii] See American Intellectual Property Law Association, Report of the Economic Survey I-117 (2013).

[iv]. Kate S. Gaudry & Sameer Vadera, The Appeal Process: The Statistical Likelihood of Success, Landslide, Vol. 8, No. 4, at 12 (March 2016).

[v]. The forwarding fee is $1,000 for small entities and $500 for micro-entities. See USPTO Fee Schedule, infra note 6.

[vi]. U.S. Patent & Trademark Office, Manual of Patent Examining Procedure, 9th ed., (Mar. 2014) (hereinafter “MPEP”) § 1207.01, available at http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s1207.html.

[vii] Karl Fazio & Kate Gaudry, 10 Years Later – A Look at the Efficacy of the Pre-Appeal Brief Conference Program, IPWatchDog, July 21, 2015.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

6 comments so far.

The Truth

April 8, 2016 09:49 pm@Curious – “this is not counting that the Board could be wrong when they affirm”. I noticed you didn’t consider the fact that the Board has often been wrong not only when they’ve affirmed, but also when they reversed. I’ve seen multiple instances where two related cases with almost identical claims have gone to the board on the exact same issue, and two separate panels have rules two different ways on the exact same issue (putting aside the fact the patent attorneys were supposed to make the board aware of the other related cases, and the examiners should have done double patenting rejections). After having seen the various panels of judges do this same thing multiple times now, the only conclusion I can make is that PTAB decisions are largely random and rarely reflect the quality of the rejection by the examiner or the quality of the arguments made by the attorney. You’ll note that there really isn’t a mechanism for the Examiner to appeal a decision (there is one where the examiner would have to convince the TC director to have the board reconsider, but I don’t know of a single instance of this happening), and for Applicants appealing PTAB decisions is extremely cost prohibitive. So there really isn’t any quality control on the board, and if you look at their production statistics you’ll see that they are by far the worst offenders when it comes to “end-loading” to meet their quotas (i.e. making large number of decisions at the end of each quarter and especially the end of the fiscal year).

The real issue for the USPTO is that at the end of the day you really can’t objectively quantify and measure quality work product.

Night Writer

March 23, 2016 01:54 pmBenny @4 and their secret always reject some applications is outrageous. I was the attorney for one case that they kept rejecting and rejecting. It cost the client big dollars and the PTO never came clean about their secret agenda. Really outrageous. I remember in an interview an examiner telling me: yes you are right. The claims are patentable over the references, but I am sure my supervisor will find more references. Again, and again. It was very confusing and frustrating.

Benny

March 22, 2016 05:38 amKen at 2 wrote “they must simply have no consequences for poor performance”.

I think that is the core of the failings of the US patent system in general – shoddy work by a semi-qualified patent examiner can translate to 7 figure loss or profit difference to the applicant (it cuts both ways), while the USPTO accepts no responsibility for their errors.

Curious

March 21, 2016 06:41 pmI appreciate the work that has gone into generating the data, but filing an “appeal” to get the Examiner to move off his/her position is something I’ve been telling clients for nearly a decade.

What I think is interesting, and is certainly worth a graph on its own, is the total percentage of at least one deficiency in the Examiner’s action. By my calculation, it is approximately 2/3rds of all appealed OAs are deficient in one way or another (this is not counting that the Board could be wrong when they affirm, but filing an appeal to the Federal Circuit is so expensive that meaningful numbers cannot be generated). This is a sad state of affairs.

Further, the Examiner’s refusal to have already allowed the application may suggest that the patentability of the application is more questionable than of other applications that the Examiner has allowed.

It also may suggest that the Examiner is one that doesn’t like to allow patent applications. See, e.g., any Examiner working in the business method art units of TC3600.

Unfortunately, this article neglects to mention one of the most important factors to consider when appealing — patent term adjustment (PTA). When faced with a final rejection, you can either file a RCE or appeal (after final amendments are usually a waste of time because they rarely get entered, so I’ll ignore that option). The filing of a RCE forever tolls Type B PTA. However, a successful appeal keeps the meter running on Type B PTA. By avoiding the filing of RCEs while filing appeals to overcome rejections, I have seen many, many instances of applicants obtaining years and years worth of PTA. For worthwhile inventions that stand the test of time, obtaining additional PTA can represent significant potential revenue sources for clients.

Aside from PTA, another downside of the RCE and Amendment route is that amending claims creates estoppel that can be better avoided by appeal.

Ken

March 21, 2016 08:37 amI guess I’m just not one of the lucky ones – my appeals lead to rejections getting rubber stamped by the supposed “conference” so it’s off to the PTAB. In one case the examiner wouldn’t even attempt to make an argument – it made me realize that they must simply have no consequences for poor performance, as long as the poor performance is in the “reject” direction.

Luis Figarella

March 21, 2016 08:16 amThanks for the stats, I too got an allowance after filing the Appeal Brief (after multiple RCEs and my ONLY in person Examiner interview, failed to do the job.

I am filing one this month and another in May (probably). As you, I’ve found the appeals brief is a wonderful way to avoid one too many RCEs…wish me luck!!!

LuF